Brain Development

Brain Development

Like the other parts of the body, different parts of the brain grow at different rates. Myelination and maturation occur in sequence, proceeding from the inner brain to the cortex and from back to front (Sowell et al., 2007). That means that the limbic system, including the amygdala, the site of intense fear and excitement, matures before the prefrontal cortex, where planning, emotional regulation, and impulse control occur.

Furthermore, pubertal hormones target the amygdala and other crucial parts of the HPA axis directly (Romeo, 2013), but full functioning of the cortex requires maturation beyond the teen years. For both of these reasons, the instinctual and emotional areas of the adolescent brain develop ahead of the reflective, analytic areas. Early puberty means emotional rushes, unchecked by caution.

A Need for Caution

Brain scans confirm that emotional control, revealed by fMRI studies, is not fully developed until adulthood, because the prefrontal cortex is limited in connections and engagement (Luna et al., 2013). When compared with the brains of emerging adults, adolescent brains show heightened arousal in the brain’s reward centers.

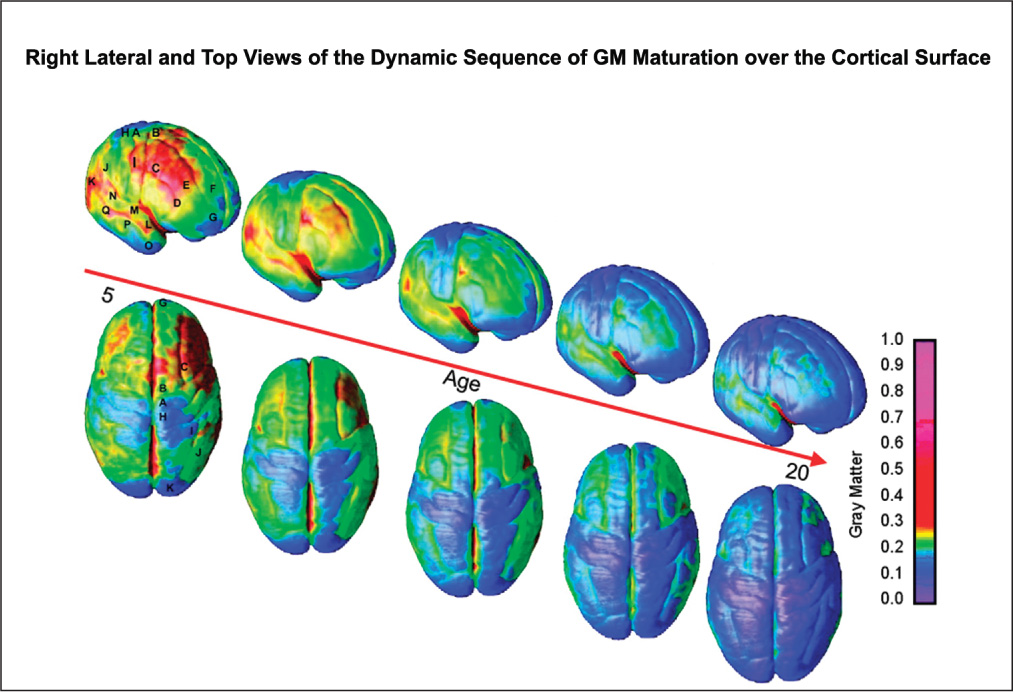

FIGURE 14.5

Same People, But Not the Same Brain These brain scans are part of a longitudinal study that repeatedly compared the proportion of gray matter from childhood through adolescence. (Gray matter refers to the cell bodies of neurons, which are less prominent with age as some neurons are unused.) Gray matter is reduced as white matter increases, in part because pruning during the teen years (the last two pairs of images here) allows intellectual connections to build. As the authors of one study that included this chart explained, teenagers may “look like an adult, but cognitively they are not there yet” (K. Powell, 2006, p. 865).Teens seek excitement and pleasure, especially the social pleasure of a peer’s admiration (Galvan, 2013). In fact, when others are watching, teens find it thrilling to take dramatic risks that produce social acclaim, risks they would not dare take alone (Albert et al., 2013).

Many types of psychopathology increase at puberty, especially when puberty is early, bringing extreme stress before the prefrontal cortex matures. Two experts explain, “higher rates of psychopathology among early maturers are expected because their slow-

The fact that the frontal lobes (prefrontal cortex) are the last to mature may explain something that has long bewildered adults: Many adolescents are driven by the excitement of new experiences, sensations, and peers—

A CASE TO STUDY

“What Were You Thinking?”

Laurence Steinberg is a noted expert on adolescence. He is also a father.

When my son, Benjamin, was 14, he and three of his friends decided to sneak out of the house where they were spending the night and visit one of their girlfriends at around two in the morning. When they arrived at the girl’s house, they positioned themselves under her bedroom window, threw pebbles against her windowpanes, and tried to scale the side of the house. Modern technology, unfortunately, has made it harder to play Romeo these days. The boys set off the house’s burglar alarm, which activated a siren and simultaneously sent a direct notification to the local police station, which dispatched a patrol car. When the siren went off, the boys ran down the street and right smack into the police car, which was heading to the girl’s home. Instead of stopping and explaining their activity, Ben and his friends scattered and ran off in different directions through the neighborhood. One of the boys was caught by the police and taken back to his home, where his parents were awakened and the boy questioned.

I found out about this affair the following morning, when the girl’s mother called our home to tell us what Ben had done…. After his near brush with the local police, Ben had returned to the house out of which he had snuck, where he slept soundly until I awakened him with an angry telephone call, telling him to gather his clothes and wait for me in front of his friend’s house. On our drive home, after delivering a long lecture about what he had done and about the dangers of running from armed police in the dark when they believe they may have interrupted a burglary, I paused.

“What were you thinking?” I asked.

“That’s the problem, Dad,” Ben replied, “I wasn’t.”

[Steinberg, 2004, pp. 51, 52]

Steinberg realized that his son was right: When emotions are intense, especially when friends are nearby, the logical part of the brain shuts down. This shutdown is not reflected in questionnaires that require teenagers to respond to paper-

the prospect of visiting a hypothetical girl from class cannot possibly carry the excitement about the possibility of surprising someone you have a crush on with a visit in the middle of the night. It is easier to put on a hypothetical condom during an act of hypothetical sex than it is to put on a real one when one is in the throes of passion. It is easier to just say no to a hypothetical beer than it is to a cold frosty one on a summer night.

[Steinberg, 2004, p. 53]

Ben reached adulthood safely. Some other teenagers, with less cautious police or less diligent parents, do not. Brain immaturity is not the origin of every “troublesome adolescent behavior,” but teenage brains have underdeveloped “response inhibition, emotional regulation, and organization” (Sowell et al., 2007, p. 59). That makes teenagers vulnerable to social pressures and stresses, which typically bombard young people today (Casey & Caudle, 2013).

The normal sequence of brain maturation (limbic system at puberty, then prefrontal cortex sometime in the early 20s) combined with the early onset of puberty means that, for contemporary teenagers, emotions rule behavior for years. The limbic system, unchecked by the slower-

It is not that the prefrontal cortex shuts down. Actually, it continues to mature throughout childhood and adolescence, and, when they think about it, adolescents are able to assess risks better than children are (Pfeiffer et al., 2011). It is the balance and coordination between the various parts of the brain that is off-

When stress, arousal, passion, sensory bombardment, drug intoxication, or deprivation is extreme, the adolescent brain is flooded with impulses that might shame adults. Teenagers brag about being so drunk, they were “wasted,” “bombed,” “smashed”—a state most adults try to avoid and would not admit. [Lifespan Link: Abuse of alcohol and other drug abuse are discussed in Chapter 16.]

Especially for Health Practitioners How might you encourage adolescents to seek treatment for STIs?

Response for Health Practitioners: Many adolescents are intensely concerned about privacy and fearful of adult interference. This means your first task is to convince the teenagers that you are nonjudgmental and that everything is confidential.

Also, unlike adults, some teenagers choose to spend a night without sleep, to eat nothing all day, to exercise in pain, or to risk parenthood or an STI by avoiding a condom. The parts of the brain dedicated to analysis are immature until years after the first hormonal rushes and sexual urges, while teenagers have access to fast cars, lethal weapons, and dangerous drugs. My friend said to his neighbor, who gave his son a red convertible for high school graduation, “Why didn’t you just give him a loaded gun?”

One example of the cautious part of the brain being overwhelmed by the emotions of the moment comes from teens sending text messages while they are driving. In one survey, 64 percent of U.S. 16-

Any decision, from whether to eat a peach to where to go to college, requires balancing risk and reward, caution and attraction. Experiences, memories, emotions, and the prefrontal cortex help all of us choose to avoid some actions and perform others. Since the reward parts of adolescents’ brains (the parts that respond to excitement and pleasure) are stronger than the inhibition parts (the parts that urge caution) (Luna et al., 2013), many adolescents act in ways that seem foolhardy to adults.

Benefits of Adolescent Brain Development

It is easy to be critical of adolescent behavior and blame it on hormones, peers, culture, or brains. Yet remember from Chapter 1 that difference is not always deficit, and that gains as well as losses are part of every stage of life. There are benefits as well as hazards in every development, including in the brain.

With increased myelination and slower inhibition, reactions become lightning fast. Such speed is valuable. For instance, adolescent athletes are potential superstars, quick and fearless as they steal a base, tackle a fullback, or sprint when their lungs feel about to burst. Ideally, coaches have the wisdom to channel such bravery.

Furthermore, as the brain’s reward areas activate positive neurotransmitters, teenagers become happier. A new love, a first job, a college acceptance, or even an A on a term paper can produce a rush of joy, to be remembered and cherished lifelong.

There are constructive good evolutionary reasons for adolescents to question tradition. As social and ecological circumstances change, someone needs to ask whether having lots of children, or eating bacon every breakfast, or burning fossil fuels, is still a good practice. If every tradition were accepted uncritically, social practices would ossify and societies would die.

Further, it is beneficial that teenagers take risks and learn new things, because “the fundamental task of adolescence—

Synaptic growth enhances moral development as well. Adolescents question their elders and forge their own standards. Values embraced during adolescence are more likely to endure than those acquired later, after brain connections are firmly established. This is an asset if adolescent values are less self-

The fact that the prefrontal cortex is still developing “confers benefits as well as risks. It helps explain the creativity of adolescence and early adulthood, before the brain becomes set in its ways” (Monastersky, 2007, p. A17). The emotional intensity of adolescents “intertwines with the highest levels of human endeavor: passion for ideas and ideals, passion for beauty, passion to create music and art” (Dahl, 2004, p. 21). As a practical application, since adolescents are learning lessons about life, those who care about the next generation need to help make sure those lessons are good ones.

SUMMING UP

The brain develops unevenly during adolescence, with the limbic system ahead of the prefrontal cortex. That makes the brain’s reward centers more active than the cautionary areas, especially when adolescents are with each other. As a result, adolescents are quick to react, before having second thoughts or considering consequences. Without impulse control, anger can lead to hurtful words or even serious injury, lust can lead to disease or pregnancy, self-