Two Modes of Thinking

Two Modes of Thinking

dual-

Advanced logic in adolescence is counterbalanced by the increasing power of intuitive thinking. A dual-

VISUALIZING DEVELOPMENT

Thinking in Adolescence

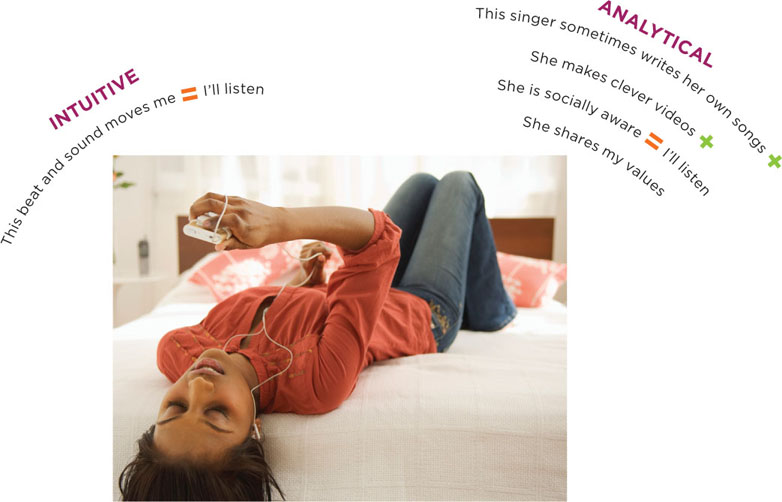

We are able to think both intuitively and analytically, but adolescents tend to rely more on intuitive thinking than do adults. As we age, we move toward more analytical processing.

JUPITERIMAGES/THINKSTOCK

As people age, their thinking tends to move from intuitive processing to more analytical processing. Virtually all cognitive psychologists note these two alternative processes and describe a developmental progression toward more dispassionate logic with maturity. However, the terms used and the boundaries between the two vary. They are roughly analogous to Kahneman’s System 1 (which “operates automatically and quickly”) and System 2 (“the conscious, reasoning self”) (Kahneman, 2011, pp. 20–

Intuition Versus Analysis

At least two modes characterize reasoning, which we refer to here as intuitive and analytical. Although they interact and can overlap, each is independent of the other (Kuhn, 2013). Although most cognitive psychologists recognize that there are two modes of thought, the terms they use vary, as do some of the specific examples. The terms include: intuitive/analytic, implicit/explicit, creative/factual, systems 1 and 2, contextualized/decontextualized, unconscious/conscious, gist/quantitative, emotional/intellectual, experiential/rational, hot/cold.

The thinking described by the first half of each pair is easier, preferred in everyday life. Sometimes, however, circumstances necessitate the second mode, when deeper thought is demanded. The discrepancy between the maturation of the limbic system and the prefrontal cortex reflects this duality. [Lifespan Link: Timing differences in maturation of various parts of the brain was discussed in Chapter 14.]

The Irrational Adolescent

Particularly in describing adolescent cognition, the terms often used to describe these two modes of thinking are intuitive/analytic:

- Intuitive thought begins with a belief, assumption, or general rule (called a heuristic) rather than logic. Intuition is quick and powerful; it feels “right.”

intuitive thought Thought that arises from an emotion or a hunch, beyond rational explanation, and is influenced by past experiences and cultural assumptions.

- Analytic thought is the formal, logical, hypothetical-

analytic thought Thought that results from analysis, such as a systematic ranking of pros and cons, risks and consequences, possibilities and facts. Analytic thought depends on logic and rationality.

deductive thinking described by Piaget. It involves rational analysis of many factors whose interactions must be calculated, as in the scale- balancing problem.

Adolescents are quick thinkers; their reaction time is shorter than at any other time of life. That typically makes them “fast and furious” intuitive thinkers, unlike their teachers and parents, who prefer slower, more analytic thinking.

Of course, when the two modes of thinking conflict, people of all ages sometimes use one mode and sometimes the other: We are all “predictably irrational” at times (Ariely, 2009). Although older adults may prefer the more thoughtful responses, it is possible to overthink a decision, to become so entangled in possibilities that no action is taken. Adolescents are impatient with adult logic, but they also can overthink. They more often err in another direction, however, with quick illogical action.

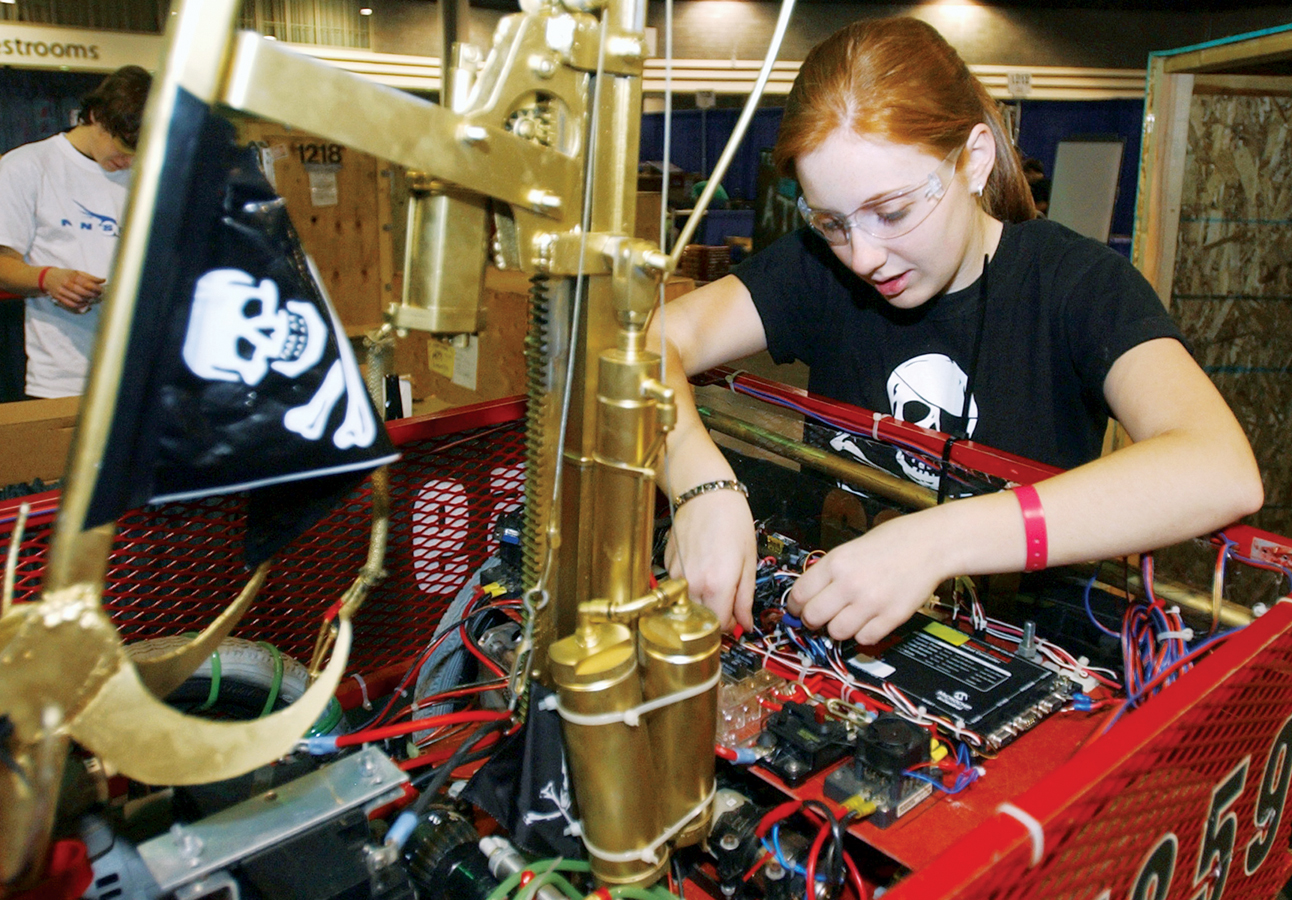

Observation Quiz Above, Melissa seems to working by herself, but what sign do you see that suggests she is part of a team who built this robot?

Answer to Observation Quiz: The flag on the robot matches her T-

Experiences and role models influence choices, not only what action to take but also what intellectual process to use to decide what to do. Conversations, observations, and debate all move thinking forward, leading to conclusions that consider more of the facts (Kuhn, 2013).

Paul Klaczynski has conducted dozens of studies comparing the thinking of children, young adolescents, and older adolescents (usually 9-

Timothy is very good-

Based on this [description], rank each statement in terms of how likely it is to be true…. The most likely statement should get a 1. The least likely statement should get a 6.

________ Timothy has a girlfriend.

________ Timothy is an athlete.

________ Timothy is popular and an athlete.

________ Timothy is a teacher’s pet and has a girlfriend.

________ Timothy is a teacher’s pet.

________ Timothy is popular.

In ranking these statements, most adolescents (73 percent) made at least one analytic error, ranking a double statement (e.g., popular and an athlete) as more likely than either of the single statements included in it (popular or an athlete). They intuitively jumped to the more inclusive statement rather than sticking to logic. Klaczynski found that almost every adolescent was analytical and logical on some of the 19 problems but not on others, with some scoring high on the same questions that others scored low on. Logical thinking improved with age and education, although not with IQ.

In other words, being smarter as measured by an intelligence test did not advance logic as much as did having more experience, in school and in life. Klaczynski (2001) concluded that, even though teenagers can use logic, “most adolescents do not demonstrate a level of performance commensurate with their abilities” (p. 854).

Preferring Emotions

What would motivate adolescents to use—

Dozens of experiments and extensive theorizing have found some answers (Albert & Steinberg, 2011). Essentially, logic is more difficult than intuition, and it requires questioning ideas that are comforting and familiar. Once people of any age reach an emotional conclusion (sometimes called a “gut feeling”), they resist changing their minds. Prejudice does not quickly disappear, because it is not seen as prejudice.

As people gain experience in making decisions and thinking things through, they become better at knowing when analysis is needed (Milkman et al., 2009). For example, in contrast to younger students, when judging whether a rule is legitimate, older adolescents are more suspicious of authority and more likely to consider mitigating circumstances (Klaczynski, 2011). Both suspicion of authority and awareness of context signify advances in reasoning, but both also complicate simple issues—

Rational judgment is especially difficult when egocentrism dominates. One psychologist discovered this personally when her teenage son phoned to be picked up from a party that had “gotten out of hand.” The boy heard

his frustrated father lament “drinking and trouble—

[Kuhn & Franklin, 2006, p. 966]

Better Thinking

Sometimes adults conclude that more mature thought processes are wiser, since they lead to caution (as in the father’s connection between “drinking and trouble”). Adults are particularly critical when egocentrism leads an impulsive teenager to risk future addiction by experimenting with drugs, or to risk pregnancy and AIDS by not using a condom.

But adults may themselves be egocentric in making such judgments if they assume that adolescents share their values. Parents want healthy, long-

A 15-

Weighing alternatives and thinking of possibilities can be paralyzing. The systematic, analytic thought that Piaget described is slow and costly, not fast and frugal, wasting precious time when a young person wants to act. Some risks are taken impulsively and foolishly, but others are premeditated, leading adolescents to make choices unlike those the parent would wish (Maslowsky et al., 2011).

As the knowledge base increases and the brain matures, as impulses become less insistent and past experiences accumulate, both modes of thought become more forceful. With maturity, education, and conversation with those who disagree, adolescents are neither paralyzed by too much analysis nor plummeted into danger via intuition. Logic increases from adolescence to adulthood (and then decreases somewhat in old age) (De Neys & Van Gelder, 2009; Kuhn, 2013).

Dual Processing and the Brain

The brain maturation process described in Chapter 14 seems to be directly related to the dual processes just explained (Steinberg, 2010). Because the limbic system is activated by puberty but the prefrontal cortex matures more gradually over time, it is easy to understand why adolescents are swayed by their intuition instead of by analysis.

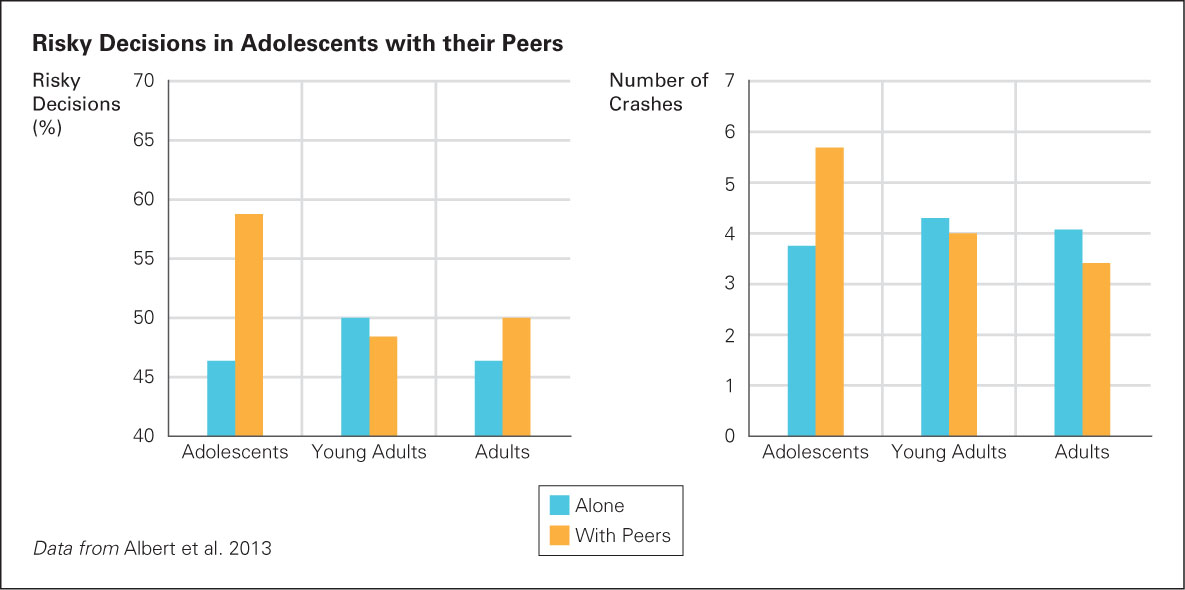

Since adolescent brains respond quickly and deeply to social rejection, it is not surprising that teens might readily follow impulses that will bring social approval. Consider the results of experiments in which adults and adolescents, alone or with peers, played a video game in which taking risks might lead to crashes or gaining points. Compared to the adults, the adolescents were much more likely to take risks and crash, especially when they were with peers (Albert et al., 2013) (see Figure 15.3).

FIGURE 15.3

Losing Is Winning In this game, risk-This explains why motor vehicle accidents in adolescence result in more deaths per vehicle than crashes in adulthood—

In the risk-

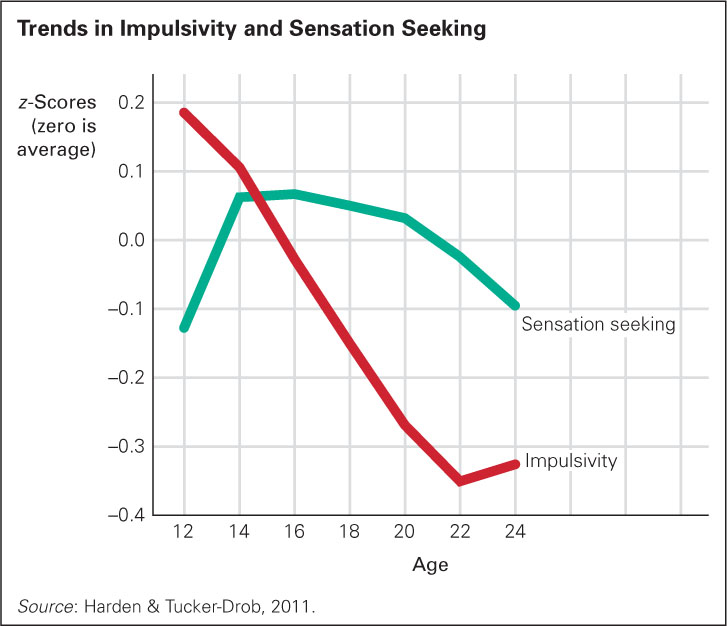

Because experiments that include brain scans are expensive, they rarely include many participants. However, other research methods confirm these results. One longitudinal survey repeatedly queried over than 7,000 adolescents, beginning at age 12 and ending at age 24. The results were “consistent with neurobiological research indicating that cortical regions involved in impulse control and planning continue to mature through early adulthood [and that] subcortical regions that respond to emotional novelty and reward are more responsive in middle adolescence than in either children or adults” (Harden & Tucker-

Specifically, this longitudinal survey traced sensation-

FIGURE 15.4

Look Before You Leap As you can see, adolescents become less impulsive as they mature, but they still enjoy the thrill of a new sensation.A burst of sensation seeking at puberty and the slow decline of impulsivity over the years of adolescence were the general trends in this study. However, trajectories varied individually: The decline in sensation seeking did not correlate with the decline in impulsivity. Thus, biology (the HPA system) is not necessarily linked to experience (which affects decision making of the prefrontal cortex) (Harden & Tucker-

For example, hormone rushes in two adolescents might produce intense and identical drives for sex, but one teenager might have had experiences (direct or via role models) that taught him or her to curb that desire, while the other has had the opposite experiences. For the first, impulsivity would decline rapidly, as practice at saying no increases. This would not be true for the second adolescent, who would seek sexual pleasure as he or she had seen on a video, heard from a friend, or had experienced before. Thus both might experience equal sensation-

SUMMING UP

Current research recognizes that there are at least two modes of cognition, here called intuitive reasoning and analytical thought. Intuitive thinking is experiential, quick, and impulsive, unlike formal operational thought. Both forms develop during adolescence, although sometimes intuitive processes crowd out analytic ones, because emotions overwhelm logic, especially when adolescents are together. Each form of thinking is appropriate in some contexts. The capacity for logical, reflective thinking increases with neurological maturation, as the prefrontal cortex matures.