Teaching and Learning

Teaching and Learning

What does our knowledge of adolescent thought imply about school? Educators, developmentalists, political leaders, and parents wonder exactly which curricula and school structures are best for 11-

To further complicate matters, adolescents are far from a homogeneous group. As a result, “some students thrive at school, enjoying and benefiting from most of their experiences there; others muddle along and cope as best they can with the stress and demands of the moment; and still others find school an alienating and unpleasant place to be” (Eccles & Roeser, 2011, p. 225).

Given all these variations, no single school structure or style of pedagogy seems best for everyone. Various scientists, nations, schools, and teachers try many strategies, some based on opposite, but logical, hypotheses. To analyze these strategies, we present definitions, facts, issues, and possibilities.

Definitions and Facts

Each year of schooling advances human potential, a fact recognized by leaders and scholars in every nation and discipline. As you have read, adolescents are capable of deep and wide-

secondary education Literally, the period after primary education (elementary or grade school) and before tertiary education (college). It usually occurs from about ages 12 to 18, although there is some variation by school and by nation.

Secondary education—traditionally grades 7 through 12—

Even such a seemingly unrelated condition as obesity among adult women in the United States is much higher among those with no high school diploma as it is among those with B.A. degrees (43 percent versus 25 percent) (National Center for Health Statistics, 2012). This is just one example from one nation, but data on almost every ailment, from every nation and every ethnic group, confirm that high school graduation correlates with better health, wealth, and family life. Some of the reasons are indirectly related to education (e.g., income and place of residence), but even when poverty and toxic neighborhoods are equalized, education confers benefits.

Partly because political leaders recognize that educated adults advance national wealth and health, every nation is increasing the number of students in secondary schools. Education is compulsory until at least age 12 almost everywhere, and new high schools and colleges open almost daily in developing nations. The two most populous countries, China and India, show dramatic growth. In India, for example, less than 1 percent of the population graduated from high school in 1950; the 2002 rate was 37 percent; the 2010 rate was 50 percent; now it is even higher (Bagla & Stone, 2013).

middle school A school for children in the grades between elementary and high school. Middle school usually begins with grade 6 and ends with grade 8.

Often, two levels of secondary education are provided. Traditionally, secondary education was divided into junior high (usually grades 7 and 8) and senior high (usually grades 9 through 12). As the average age of puberty declined, middle schools were created for grades 6 to 8, and sometimes for grades 5 to 8.

Every nation seeks to educate its citizens. As reviewed in Chapter 12, two international tests, the TIMSS (Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study) and the PIRLS (Progress in International Reading Literacy Study), find that the United States is only middling among developed nations in student learning. A third set of international tests, the PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment), to be explained soon, places U.S. students even lower.

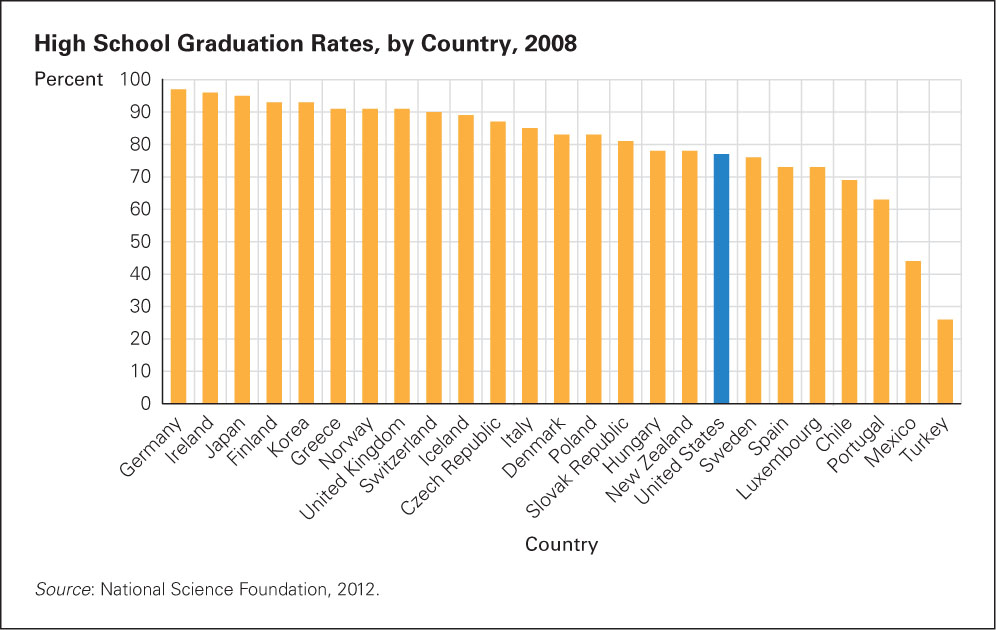

In many nations, scores on those three international tests as well as other metrics compel reexamination of school policies and practices. That certainly is true in the United States, which lags behind other developed nations in high school graduation rate (see Figure 15.6).

FIGURE 15.6

Children Left Behind High school graduation rates in almost every nation and ethnic group are improving. However, the United States still lags behind other nations, and ethnic differences persist, with the rate among Native-Middle School

School dropout rates are affected by middle school. As one scholar wrote: “Long-

Many developmentalists find middle schools to be “developmentally regressive” (Eccles & Roesner, 2010, p. 13), which means learning goes backward. Entering a new school is particularly stressful during the growth spurt or the onset of sexual characteristics (Riglin et al., 2013). Adjusting to middle school is bound to be stressful, as teachers, classmates, and expectations all change.

IMAGEBROKER/ALAMY

Increasing Behavioral Problems

For many middle school students, academic achievement slows down and behavioral problems increase. Puberty itself is part of the problem. At least for other animals studied, especially when they are under stress, learning is reduced at puberty (McCormick et al., 2010).

Especially for Teachers You are stumped by a question your student asks. What do you do?

Response for Teachers: Praise a student by saying, “What a great question!” Egos are fragile, so it’s best to always validate the question. Seek student engagement, perhaps asking whether any classmates know the answer or telling the student to discover the answer online or saying you will find out. Whatever you do, don’t fake it—

Biological and psychological stresses of puberty are not the only reason learning suffers in early adolescence. Cognition matters too: how much new middle school students like their school affects how much they learn (Riglin et al., 2013).

Unfortunately, many students have reasons to dislike middle school, especially compared to elementary school. Middle schools undercut student–

High-

A CASE TO STUDY

James, the High-Achieving Dropout

A longitudinal study in Massachusetts followed children from preschool through high school. James was one of the most promising of these students. In his early school years, he was an excellent reader whose mother took great pride in him, her only child. Once James entered middle school, however, something changed:

Although still performing well academically, James began acting out. At first his actions could be described as merely mischievous, but later he engaged in much more serious acts, such as drinking and fighting, which resulted in his being suspended from school.

[Snow et al., 2007, p. 59]

Family problems increased. James and his father blamed each other for their poor relationship, and his mother bragged “about how independent James was for being able to be left alone to fend for himself,” while James “described himself as isolated and closed off” (Snow et al., 2007, p. 59).

James said, “The kids were definitely afraid of me but that didn’t stop them” from associating with him (Snow et al., 2007, p. 59). James’s experience is not unusual. Generally, aggressive and drug-

This is not true only for African American boys like James. Research from Germany, Canada, and Israel found that mathematically gifted girls are particularly likely to underachieve (Boehnke, 2008). But girls have one advantage over boys in secondary school—

At the end of primary school, James planned to go to college; in middle school, he said he had “a complete lack of motivation”; in tenth grade, he left school.

As was true for James, the early signs of a future high school dropout are found in middle school. Those students who leave without graduating tend to be low-

Finding Acclaim

To pinpoint the developmental mismatch between students’ needs and the middle school context, note that just when egocentrism leads young people to feelings of shame or fantasies of stardom (the imaginary audience), schools typically require them to change rooms, teachers, and classmates every 40 minutes or so. That makes both public acclaim and new friendships difficult to achieve.

Recognition for academic excellence is especially elusive because middle school teachers mark more harshly than their primary school counterparts. Effort per se is not recognized, and achievement that was earlier called outstanding is now only average. Acclaim for after-

Since public acclaim escapes them, many middle school students seek acceptance from their peers. Bullying increases, physical appearance becomes more important, status symbols are displayed (from gang colors to trendy sunglasses), expensive clothes are coveted, and sexual conquests are flaunted. Of course, much depends on the cultural context, but almost every middle school student seeks peer approval in ways that adults disapprove (Véronneau & Dishion, 2010).

Coping with Middle School

One way to cope with stress is directly cognitive, that is, blaming classmates, teachers, parents, governments for any problems. This may explain the surprising results of a Los Angeles study: Students in schools that were more ethnically mixed felt safer and less lonely. They did not necessarily have friends from other groups, but students who felt rejected could “attribute their plight to the prejudice of other people” rather than blame themselves (Juvonen et al., 2006, p. 398). Furthermore, since each group was a minority, the students tended to support and defend other members of their group, so each individual had some natural allies.

Some students avoid failure by simply not making an effort; that way, they can blame a low grade on a lack of trying (“I didn’t study”) rather than on stupidity. Pivotal is their understanding of their own potential.

entity theory of intelligence An approach to understanding intelligence that sees ability as innate, a fixed quantity present at birth; those who hold this view do not believe that effort enhances achievement.

If they hold to the entity theory of intelligence (i.e., believing that ability is innate, a fixed quantity present at birth), then nothing they do can improve their academic skill. They consider themselves as innately incompetent at math, or reading, or whatever, and mask that reality by claiming not to study, try, or care. Thus, entity belief reduces stress, but it also reduces learning.

incremental theory of intelligence An approach to understanding intelligence that holds that intelligence can be directly increased by effort; those who subscribe to this view believe they can master whatever they seek to learn if they pay attention, participate in class, study, complete their homework, and so on.

By contrast, if adolescents adopt the incremental theory of intelligence (i.e., believing that intelligence can increase if they try to master whatever they seek to learn), they will pay attention, participate in class, study, complete their homework, and learn. That is also called mastery motivation, an example of intrinsic motivation. [Lifespan Link: Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation were discussed in Chapter 10.]

This is not just a hypothesis. In the first year of middle school, students with entity beliefs do not achieve much, whereas those with mastery motivation improve academically. In one study, students in their first year of middle school were taught eight lessons (such as ways to “grow your intelligence”) designed to convey the idea that being smart is incremental. Especially if they had formerly held the entity theory, their performance improved compared to the students in other classes (Blackwell et al., 2007).

Especially for Middle School Teachers You think your lectures are interesting and you know you care about your students, yet many of them cut class, come late, or seem to sleep through it. What do you do?

Response for Middle School Teachers: Students need both challenge and involvement; avoid lessons that are too easy or too passive. Create small groups; assign oral reports, debates, and role-

Teachers themselves were surprised at the effect. A “typical” comment came from a teacher who explained that a boy

who never puts in any extra effort and doesn’t turn in homework on time actually stayed up late working for hours to finish an assignment early so I could review it and give him a chance to revise it. He earned a B+ … he had been getting C’s and lower.

[quoted in Blackwell et al., 2007, p. 256]

The idea that skills can be mastered motivates the learning of social skills as well as academic subjects (Dweck, 2013). Social skills are particularly important in adolescence because students want to know how to improve their peer relationships.

The contrast between entity and incremental theories is apparent not only for individual adolescents but also for teachers, parents, schools, and cultures. If the hidden curriculum endorses competition among students, then everyone believes the entity theory, and students are unlikely to help each other (Eccles & Roeser, 2011). If a teacher believes that children cannot learn much, then they won’t.

International comparisons reveal that educational systems that track students into higher or lower classes, that expel low-

High School

Many of the patterns and problems of middle school continue in high school. As we have seen, adolescents can think abstractly, analytically, hypothetically, and logically as well as personally, emotionally, intuitively, and experientially. The curriculum and teaching style in high school often require the former mode.

MELANIE STETSON FREEMAN/THE CHRISTIAN SCIENCE MONITOR / GETTY IMAGES

The College-Bound

Especially for High School Teachers You are much more interested in the nuances and controversies than in the basic facts of your subject, but you know that your students will take high-

Response for High School Teachers: It would be nice to follow your instincts, but the appropriate response depends partly on pressures within the school and on the expectations of the parents and administration. A comforting fact is that adolescents can think about and learn almost anything if they feel a personal connection to it. Look for ways to teach the facts your students need for the tests as the foundation for the exciting and innovative topics you want to teach. Everyone will learn more, and the tests will be less intimidating to your students.

From a developmental perspective, the fact that high schools emphasize formal thinking makes sense, since many older adolescents are capable of abstract logic. High school teachers typically assume that their pupils have mastered formal thinking and do not attempt to teach them how to think that way (Kuhn & Franklin, 2006). That lack of instruction might hinder them in college, when formal thinking is expected.

The United States is trying to raise standards so that all high school graduates will be ready for college. For that reason, schools are increasing the number of students who take classes that are assessed by externally scored exams, either the IB (International Baccalaureate) or the AP (Advanced Placement). Such classes have high standards and satisfy a number of college requirements.

Unfortunately, merely taking an AP class does not necessarily lead to college readiness (Sadler et al., 2010). Some students are discouraged from taking the AP exams. However, of the students who graduated from U.S. high schools in 2012, 32 percent had taken at least one AP exam and one-

Of course, college credit is not the only measure of high school rigor. Another indicator is an increase in the requirements to receive an academic diploma. (In many U.S. schools, no one is allowed to earn a vocational or general diploma unless parents request it.) Graduation requirements usually include two years of math beyond algebra, two years of laboratory science, three years of history, and four years of English. Learning a language other than English is often required as well.

high-

In addition to these required courses, many U.S. states now also require students to pass a high-

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

Testing

Students in the United States take many more tests than they did even a decade ago. This includes many high-

Testing begins long before high school: many students take high-

All tests are also high stakes for teachers, who can earn extra pay or lose their job based on what their students have learned, and for schools, which may gain resources, or be closed, because of test scores. Opposing perspectives on testing are voiced in many schools, parent groups, and state legislatures. In 2013, Alabama dropped its high stakes test for graduation while Pennsylvania instituted such a test. In the same year Texas reduced the number of tests required for graduation from 15 (the result of a 2007 law) to 4 (Rich, 2013).

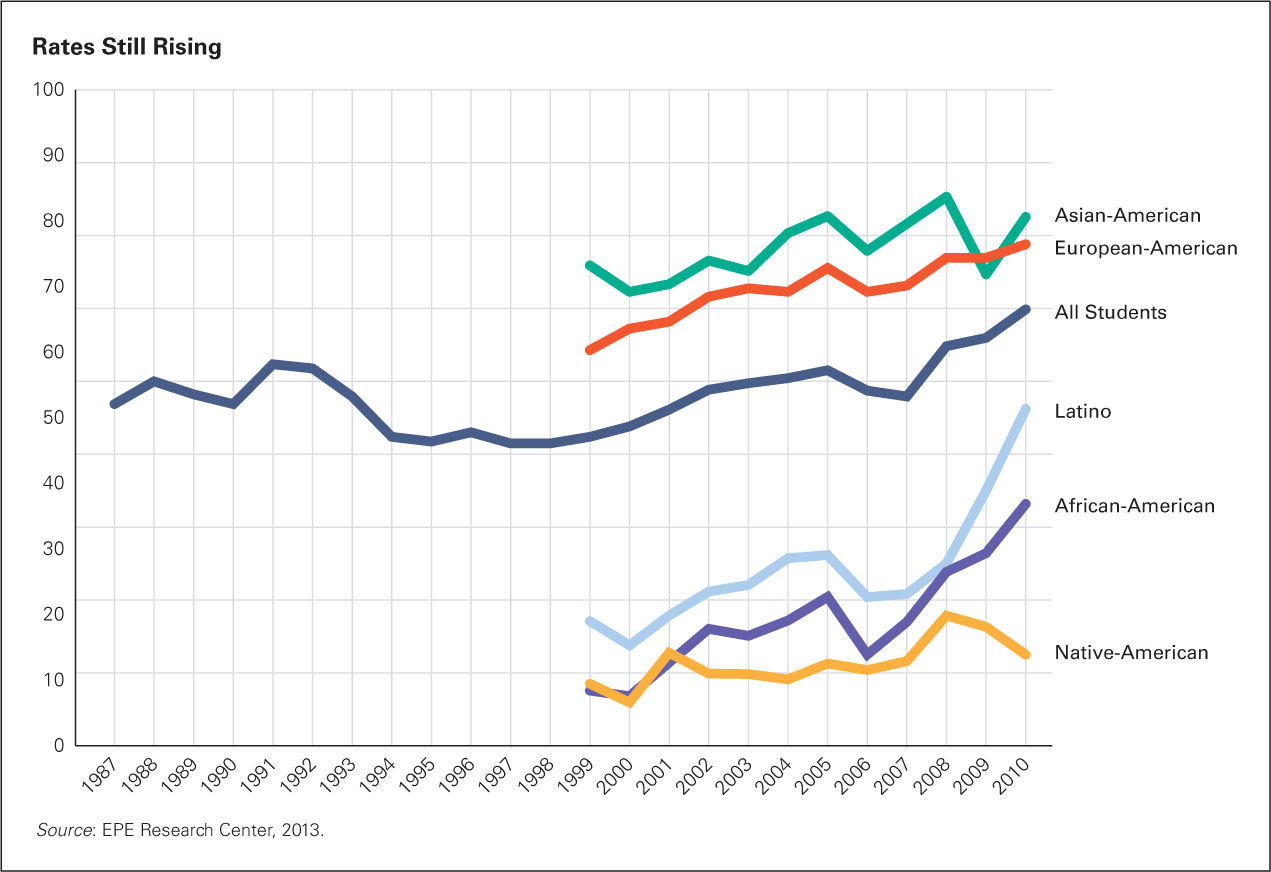

Overall, high school graduation rates in the United States have increased every year for the past decade, reaching 78 percent in 2010 (see Figure 15.7). Some say that tests and standards are part of the reason.

FIGURE 15.7

Graduation Rates on the Rebound The U.S. graduation rate has reached its highest point thus far. Every racial and ethnic group posted solid gains in recent years. The gap between Asian/White and the three other groups is almost always the result of differences in socioeconomic status—However, others fear that students who do not graduate are discouraged. This is a particular concern for students with learning disabilities, one-

Even those who pass may be less excited about education. A panel of experts found that too much testing reduces learning rather than advances it (Hout & Elliot, 2011). But how much is “too much”?

One expert recommends “using tests to motivate students and teachers for better performance” (Walberg, 2011, p. 7). He believes that well-

Ironically, just when more U.S. schools are raising requirements, many East Asian nations, including China, Singapore, and Japan (all with high scores on international tests), are moving in the opposite direction. Particularly in Singapore, national high-

A team of Australian educators reviewed all the evidence and concluded:

What emerges consistently across this range of studies are serious concerns regarding the impact of high stakes testing on student health and well-

[Polesel et al., 2012, p. 5]

International data support both sides of this controversy. One nation whose children generally score well is South Korea, where high-

On the opposite side of the globe, students in Finland also score very well on international tests, and yet they have no national tests until the end of high school. Nor do they spend much time on homework or after-

Soon data may clarify if U.S. testing has gone too far. If Finland and Singapore continue to do well, and improvement lags in North America, that suggests that tests are not helping. Ideally, either those who support high-

Those Who Do Not Go to College

Many high school graduates (about 70 percent) enter college. However, only a fourth of those entering public community colleges complete their Associate degree within three years, and almost half of those entering public or private four-

These sobering statistics underlie another debate among educators. Should students be encouraged to “dream big” early in high school, aspiring for tertiary learning? This suggestion originates from studies that find a correlation between dreaming big in early adolescence and going to college years later (Domina et al., 2011a, 2011b). Others suggest that college is a “fairy tale dream” that may lead to low self-

Business leaders have another concern: that high school graduates are not ready for the demands of work because their education has been too abstract. They have not learned enough through discussion, emotional maturation, and real-

We believe that professional success today and in the future is more likely for those who have practical experience, work well with others, build strong relationships, and are able to think and do, not just look things up on the Internet.

[Stephens & Richey, 2013]

In the United States, some 2,500 career academies (small institutions of about 300 students each) prepare students for specific jobs. Seven years after graduation, students who were in career academies earn about $100 more a month than do other students who applied but could not enroll because there was no room (Kemple, 2008). They are also more likely to be married (38 percent versus 34 percent) and living with their children (51 percent versus 44 percent).

These programs are available to relatively few high school students, in part because the focus is on college for all. Indeed, suggesting that a student should head away from college is often considered racist, classist, sexist, or worse. Everyone agrees that adolescents need to be educated for life as well as college, but it is difficult to decide what that means.

Measuring Practical Cognition

Employers usually provide on-

PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) An international test taken by 15-

A third set of international tests of math, science, and reading is the PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment), taken by 15-

The tests are designed to generate measures of the extent to which students can make effective use of what they have learned in school to deal with various problems and challenges they are likely to experience in everyday life.

[PISA, 2009, p. 12]

For example, among the 2012 math questions is this one:

Chris has just received her car driving license and wants to buy her first car. This table below shows the details of four cars she finds at a local car dealer.

| Model | Alpha | Bolte | Castel | Dezal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2003 | 2000 | 2001 | 1999 |

| Advertised price (zeds) | 4800 | 4450 | 4250 | 3990 |

| Distance travelled (kilometers) | 105 000 | 115 000 | 128 000 | 109 000 |

| Engine capacity (liters) | 1.79 | 1.796 | 1.82 | 1.783 |

What car’s engine capacity is the smallest?

- A. Alpha

- B. Bolte

- C. Castel

- D. Dezal.

For that and the other questions on the PISA, the calculations are quite simple—

Overall, the U.S. students did worse on the PISA than on the PIRLS or TIMSS. In the latest PISA overall results (for reading, science, and math), China, Singapore, and South Korea were at the top; Finland improved dramatically to rank close to the top, followed immediately by Canada. The United States scored near average or below average in math, reading, and science (see Table 15.1). Four factors correlate with high achievement (OECD, 2010, p. 6):

- Leaders, parents, and citizens overall value education, with individualized approaches to learning so that all students learn what they need.

- Standards are high and clear, so every student knows what he or she must do, with a “focus on the acquisition of complex, higher-

order thinking skills.” - Teachers and administrators are valued, given “considerable discretion … in determining content” and sufficient salary as well as time for collaboration.

- Learning is prioritized “across the entire system,” with high-

quality teachers working in the most challenging environments.

| Education System | Average Score 2012 | Average Score 2009 | Education System | Average Score 2012 | Average Score 2009 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shanghai- |

613 | 600 | Iceland | 493 | 507 |

| Singapore | 573 | 562 | Norway | 489 | 498 |

| Hong Kong- |

561 | 555 | Portugal | 487 | 487 |

| South Korea | 554 | 546 | Italy | 485 | 483 |

| Japan | 536 | 529 | Spain | 484 | 483 |

| Switzerland | 531 | 534 | Russian Federation | 482 | 468 |

| Netherlands | 523 | 526 | United States | 481 | 487 |

| Finland | 519 | 541 | Sweden | 478 | 494 |

| Canada | 518 | 527 | Hungary | 477 | 490 |

| Poland | 518 | 495 | Florida | 467 | n/a |

| Belgium | 515 | 515 | Israel | 466 | 447 |

| Germany | 514 | 513 | Turkey | 448 | 445 |

| Austria | 506 | 496 | Chile | 423 | 421 |

| Australia | 504 | 514 | Mexico | 413 | 419 |

| Ireland | 501 | 487 | Uruguay | 409 | 427 |

| Denmark | 500 | 503 | Brazil | 391 | 386 |

| New Zealand | 500 | 519 | Argentina | 388 | 388 |

| Czech Republic | 499 | 493 | Tunisia | 388 | 371 |

| France | 495 | 497 | Jordan | 386 | 387 |

| United Kingdom | 494 | 492 | Indonesia | 375 | 371 |

| Source: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), 2012. | |||||

The PISA and international comparisons of high school dropout rates suggest that U.S. secondary education can be improved, especially for those who do not go to college. Surprisingly, students who are capable of passing their classes, at least as measured on IQ tests, drop out almost as often as those who are less capable. Persistence, engagement, and motivation seem more crucial than intellectual ability (Archambault et al., 2009; Tough, 2012).

An added complication in deciding what are the best middle schools and high schools comes from the variation among adolescents: some thoughtful, some impulsive, some ready for analytic challenges, some egocentric, and all needing personal encouragement. A study of student emotional and academic engagement from the fifth to the eighth grade found that, as expected, the overall average was a slow and steady decline of engagement, but a distinctive group (about 18 percent) were highly engaged throughout, and another distinctive group (about 5 percent) experienced precipitous disengagement year by year (Li & Lerner, 2011).

Thus schools and teachers need many strategies to educate adolescents, since they themselves vary. Now let us return to general conclusions for this chapter.

The cognitive skills that boost national economic development and personal happiness are creativity, flexibility, relationship building, and analytic ability. Whether or not an adolescent is college bound, those skills are exactly what adolescents can develop—

As you have read, every researcher believes that the logical, social, and creative potential of the adolescent mind is not always realized, but that it can be. Does that belief mean that this chapter ends on a hopeful note?

SUMMING UP

Middle schools tend to be less personal, less flexible, and more tightly regulated than elementary schools, which may contribute to a general finding: declining student achievement. Teachers grade more harshly, students are more rebellious, and every teacher has far more students—