Growth and Strength

Growth and Strength

Biologically, the years from ages 18 to 25 are prime time for hard physical work and safe reproduction. However, as you will see, the ability of an emerging adult to move stones, plow fields, or haul water better than older adults is no longer admired, and if a contemporary young couple had a baby every year, their neighbors would be more appalled than approving.

Strong and Active Bodies

Maximum height is usually reached by age 16 for girls and 18 for boys, except for a few late-

Especially for a Competitive Young Man Given the variations in aging muscle, how might a 20-

Response for a Competitive Young Man: He might propose a stair-

For both sexes, muscles can be powerful. Emerging adults are more able than people of any other age to race up a flight of stairs, lift a heavy load, or grip an object with maximum force. Strength gradually decreases over the decades of adulthood, with some muscles weakening more quickly than others. Back and leg muscles shrink faster than the arm muscles, for instance (McCarter, 2006). This is apparent in older baseball players who still hit home runs long after they no longer steal bases.

Every body system—

In a large survey, 96.1 percent of young adults (aged 18 to 24) in the United States rated their health as good, very good, or excellent, whereas only 3.9 percent rated it as fair or poor (National Center for Health Statistics, 2012). Similarly, 95.3 percent of 18-

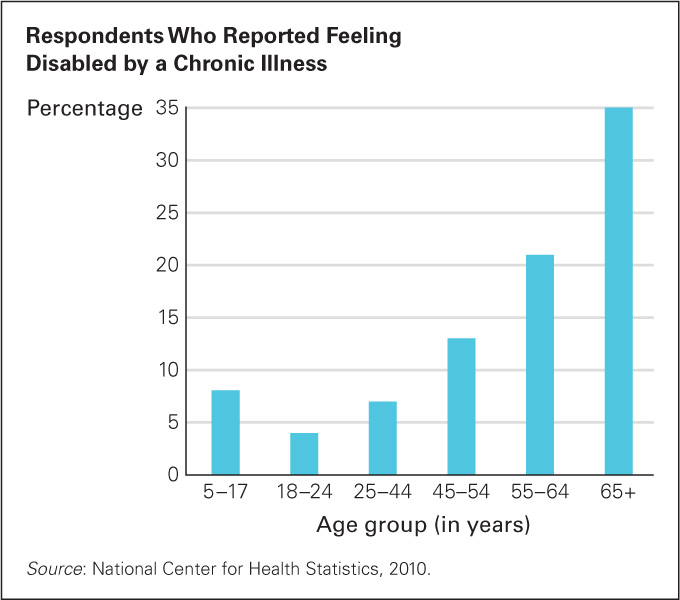

FIGURE 17.1

Strong and Independent Looking at this graph, do you wonder why twice as many 5-However, some emerging adults have health problems that they may ignore. Doctors have told 15 percent of 18-

Lifelong, many serious conditions can be avoided or ameliorated with preventive medicine. If this were the only way to be healthy, then most emerging adults would be sick, because they avoid medical professionals unless they are injured or pregnant. Thirty percent of this age group in the United States has no usual source of medical care (National Center for Health Statistics, 2012). Perhaps as a result, the average emerging adult sees a health professional once a year, compared with about 10 annual medical visits for the typical adult aged 75 or older. In fact, one-

Emblematic of the carelessness of emerging adults regarding health is hand washing among students at a college in Ontario, where a viral epidemic led the school’s administration to advocate—

Similarly, while the Centers for Disease Control recommends the flu shot each year for everyone over 6 months of age, only about one-

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

Ages and Stages

In many ways, a person aged 18 to 25 is no different from a person a few years younger or older. The age parameters of emerging adulthood are somewhat arbitrary, unlike earlier in life, when physical maturation is closely tied to chronological age and developmental stage

Earlier in life, age signifies growth and abilities. No one would mistake a 3-

For adults, however, chronological age is an imperfect guide. A 40-

Nor do adult social roles follow strict age parameters. Virtually all children live with their parents and go to school, but a cross section of 40-

Then why do developmental scientists cluster adults into chronological age groups, reporting differences between one group and another? Every researcher in developmental psychology does that, as do textbooks such as this one. One indication of the fluidity of adult age boundaries is that textbooks use various ages to indicate the beginning of adulthood or late adulthood. Nonetheless, chronological ages are always given. Why?

There are three reasons. The first is that age matters to adults as they live their lives. People note birthdays, especially the ones ending in 5 or 0, and say “I’m too old to…” or “It’s about time for you to….”

The second reason is that cohort matters. For example, because the Internet, cell phones, and social networking are relatively new, the emerging adult generation has a different life pattern than older adults did. Indeed, almost all young people meet potential dates and many meet marriage partners online. That has changed courtship patterns, changes that are reflected in any discussion of this generation.

Finally, maturation and experience accumulate. Of course, some people age faster than others, but every aspect of the body and brain is affected by time. Despite variability, many characteristics (vision, hearing, reaction time) of young adults differ from those of people in middle or late adulthood. The study of human development must delineate the impact of maturation.

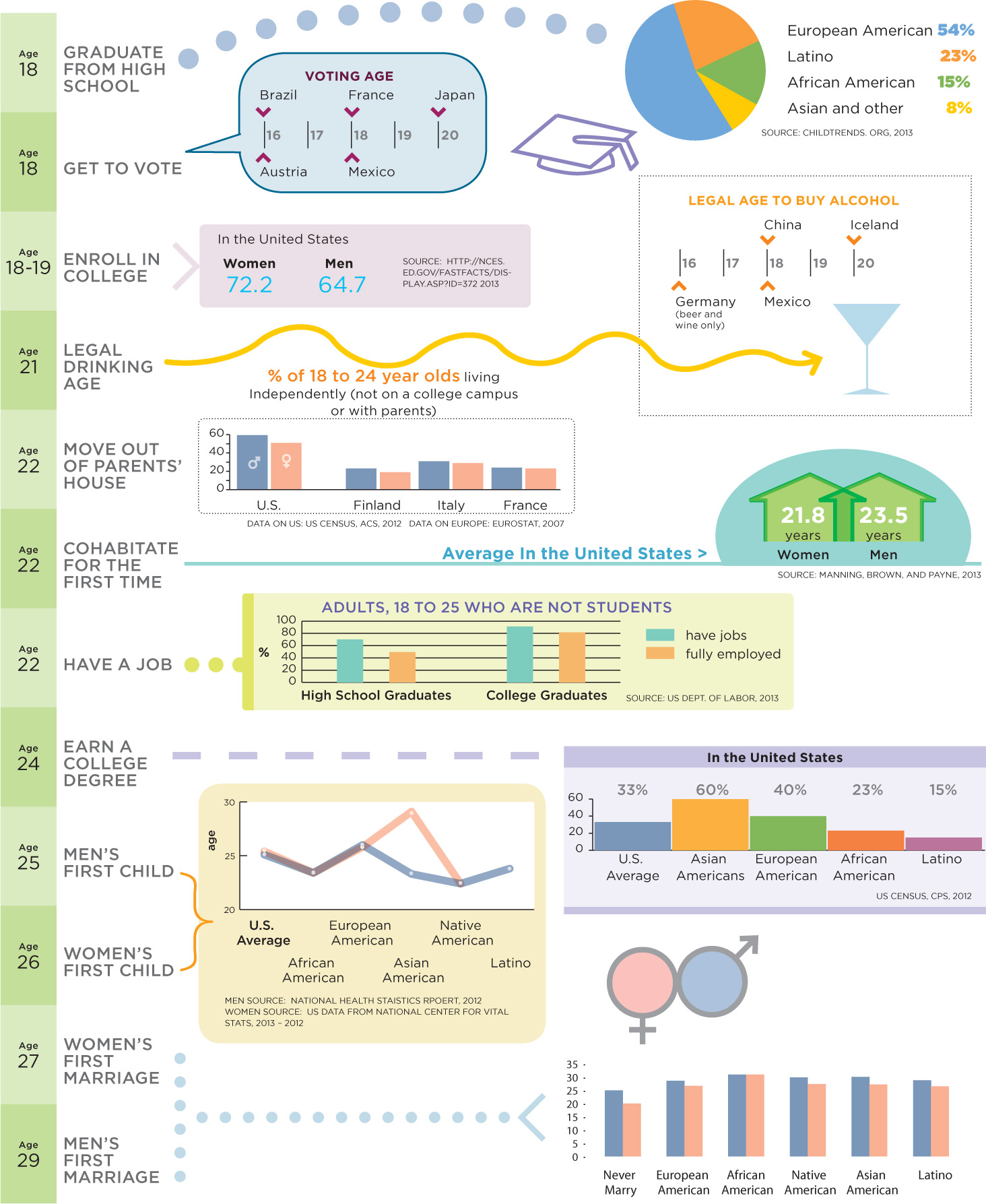

The goal of developmental study remains to understand change over time in order to help all people fulfill their potential. Since people follow patterns that vary by birthdays, cohort, and maturation, we need to know what those patterns are. Chronological boundaries help with that. (See Visualizing Development, p. 494, for the average age of important life events for the current cohort of emerging adults.)

Bodies in Balance

| Age Group | Annual Rate per 100,000 |

|---|---|

| 15– |

6 |

| 25– |

17 |

| 35– |

59 |

| 45– |

205 |

| 55– |

515 |

| 65– |

1,157 |

| 75– |

2,662 |

| 85 + | 7,009 |

| Source: National Center for Health Statistics, 2013. | |

Fortunately, bodies are naturally healthy during emerging adulthood. The immune system is strong, fighting off everything from the sniffles to cancer and responding well to vaccines (Grubeck-

Rates of illness are so low that many diagnostic tests, such as PSA (for prostate cancer), mammograms (for breast cancer), and colonoscopies (for colon cancer), are not recommended until middle age or later, unless family history or warning signs suggest otherwise. These tests are more likely to be harmful to young adults because of false positives than to benefit them because of early detection. Fatal disease is rare worldwide during emerging adulthood, as Table 17.1 details for the United States. (see page 495).

This does not mean that emerging adults are unaffected by the passing years. The process of aging, called s enescence, begins in late adolescence. [Lifespan Link: Senescence is discussed in more detail in Chapter 20.] However, because of three biological processes we now describe—

VISUALIZING DEVELOPMENT

Highlights in the Journey to Adulthood

Organ Reserve

organ reserve The capacity of organs to allow the body to cope with stress, via extra, unused functioning ability.

Organ reserve refers to the extra power that every organ is capable of producing when needed. That reserve power decreases each year, but it usually does not matter because people rarely need to draw on it. Bodies function well unless major stress, genetic weakness, or aging has caused that extra strength to be used up.

Bodies have a muscle reserve as well, directly related to physical strength. Maximum strength potential typically begins to decline by age 25. However, few adults develop all their possible strength, and even if they did, 50-

The most important muscle of all, the heart, shows a similar pattern. The heart is amazingly strong during emerging adulthood: Only 1 in 50,000 North American young adults dies of heart disease each year. The average maximum heart rate—

Homeostasis

homeostasis The adjustment of all the body’s systems to keep physiological functions in a state of equilibrium. As the body ages, it takes longer for these homeostatic adjustments to occur, so it becomes harder for older bodies to adapt to stress.

All the parts of the body work in harmony. Homeostasis—a balance between various parts of the body systems—

Homeostasis works most quickly and efficiently during emerging adulthood. Thus, as long as they get enough sleep and nourishment, emerging adults are less likely to be sick, fatigued, or obese than older adults. When they catch a cold, they are down for a day or two; older adults often complain that they cannot “shake” a virus.

Each person’s homeostatic systems are affected by age and past experiences, as well as by genes. For example, reaction to weather depends partly on childhood climate (an African may be cold when her roommate from northern Europe is warm), and younger people are generally warmer than older ones. If two people share a bed, one may want more blankets, which is why modern electric blankets have dual controls. Your mother may tell you to put on a sweater because she is cold.

Allostasis

allostasis A dynamic body adjustment, related to homeostasis, that affects overall physiology over time. The main difference is that homeostasis requires an immediate response whereas allostasis requires longer-

Related to homeostasis is allostasis, a dynamic body adjustment that affects overall physiology. The main difference between homeostasis and allostasis is time: Homeostasis requires an immediate response from the body systems, whereas allostasis refers to longer-

For example, how much a person eats daily is affected by many factors related to appetite—

Eating is related to a broader set of human needs: how emotionally satisfied or distressed a person is. Many people overeat when they are upset, and eat less when they have recently exercised—

Over the longer term, allostasis adjusts to whatever the person eats, breathes, exercises, and so on. If a person is hungry for several weeks, the body adjusts. That allostatic adjustment is why a heavy meal suddenly consumed by a starving person might result in vomiting or diarrhea. Allostasis for a starving person requires gradual readjustment (small, digestible meals) when food is plentiful. Similarly, if a long-

Over the years, allostasis becomes more crucial: If a person overeats or starves day after day, the body adjusts, but that takes a toll on health. In medical terminology, that person has an increased allostatic load because the body’s adjustment results in a burden that may impair long-

Thus, overeating and underexercising require not just adjustment for each moment (homeostasis) but also adjustment over decades. One heavy meal reduces appetite for the next few hours (homeostasis); years of obesity put increasing pressure on the allostatic system, so a new stress (such as running up three flights of stairs) may cause a major breakdown (such as a heart attack).

All Three Together

Add organ reserve to homeostasis and allostasis and it is clear why health habits in emerging adulthood affect vitality in old age. Because of organ reserve, a heart attack is unlikely before midlife, but years of physical stresses affect overall body functioning. Thus a person may have a heart attack at age 50 because of obesity and smoking that began at age 20.

Young adults rarely experience serious illness because all three aspects of body functioning—

Even in the smaller changes of aging, such as the wearing down of the teeth or loss of cartilage in the knees, serious reductions are not normally evident until later in life. For example, brushing and flossing the teeth reduces bacteria of the mouth, but all three aspects of body functioning prevent gum disease in emerging adulthood even with poor oral hygiene and never seeing a dentist. The consequences appear much later, when tooth loss reflects decades of taking teeth for granted.

For everyone, the immune system is a strong and vital part of homeostasis, which is why emerging adults are so healthy. But don’t make the mistake of thinking that eventual illness is simply the result of age and fate. Daily life makes a difference, as proven by astronauts. Those chosen to fly in space are relatively young and in excellent health, with strong immune systems. However, after a space flight, the immune system shows temporary but severe loss. That proves that the body is affected by much more than genes and aging (Crucian et al., 2013).

Appearance

Partly because of their overall health, strength, and activity, most emerging adults look vital and attractive. The oily hair, pimpled faces, and awkward limbs of adolescence are gone, and the wrinkles and hair loss of middle adulthood have not yet appeared. Obesity is less common during emerging adulthood than in adulthood.

The organ that protects people from the elements, the skin, is clear and taut, characteristics that “can change quite drastically” with time (Whitbourne & Whitbourne, 2011, p. 66). The attractiveness of youth is one reason that newly prominent fashion models, popular singers, and film stars tend to be in their early 20s, looking fresh and glamorous.

Vanity about personal appearance is not admired, so few emerging adults admit that they are intensely concerned about their looks. That was one conclusion from a study of 19-

Concern about appearance may be connected to sexual drives, since appearance attracts sexual interest, and young adults hope to be attractive. Furthermore, in these years many people seek employment. Attractiveness (in clothing, body, and face) correlates with better jobs and higher pay (Fletcher, 2009). Women particularly focus on appearance, especially weight, because how they look is important for both dating and employment (Fikkan & Rothblum, 2012; Morgan et al., 2012).

No wonder emerging adults try to look their best. Usually they succeed.

Staying Healthy

Emerging adults experiment and select from many options. We focus now on two vital choices that help emerging adults stay healthy: exercise and nutrition.

Exercise

Exercise at every stage of life protects against serious illness, even if a person smokes and overeats. Exercise reduces blood pressure, strengthens the heart and lungs, and makes depression, osteoporosis, heart disease, arthritis, and even some cancers less likely. Health benefits from exercise are substantial for men and women, old and young, former sports stars and those who never joined an athletic team.

By contrast, sitting for long hours correlates with almost every chronic illness, especially heart disease and diabetes, both of which pose additional health hazards. Even a little movement—

The health consequences of inactivity in early adulthood have been found in dozens of studies. One of the best is CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Adulthood) that began with over four thousand healthy 18-

Especially for Emerging Adults Seeking a New Place to Live People move more often between the ages of 18 and 25 than at any later time. Currently, real estate agents describe sunlight, parking, and privacy as top priorities for their young clients. What else might emerging adults ask when seeking a new home?

Response for Emerging Adults Seeking a New Place to Live: Since neighborhoods have a powerful impact on health, a person could ask to see the nearest park, to meet a neighbor who walks to work, or to contact a neighborhood sports league.

Fortunately, most emerging adults are quite active, getting aerobic exercise by climbing stairs, jogging to the store, joining intramural college and company athletic teams, playing at local parks, biking, hiking, swimming, and so on. In the United States, emerging adults walk more and drive less than older adults, and 61 percent of them reach the standard of exercising 30 minutes a day, five days a week. That 61 percent is higher than any other age group, and higher than the percentage of young adults who achieved that standard a decade ago (52 percent).

Past generations quit exercising when marriage, parenthood, and career became more demanding. Young adults today, aware of this tendency, can choose friends and communities that support, rather than preclude, staying active. Two factors can encourage activity:

- Friendship. People exercise more if their friends do so, too. Because social networks typically shrink with age, adults need to maintain, or begin, friendships that include movement, such as meeting a friend for a jog instead of a beer or playing tennis instead of going to a movie.

- Communities. Some neighborhoods have walking and biking paths, ample fields and parks, and subsidized pools and gyms. Most colleges provide these amenities, which increases the exercise of students. Health experts cite extensive research showing that community design can have a positive effect on the levels of obesity, hypertension, and depression (Bors et al., 2009).

Eating Well

Nutrition is another lifelong habit embedded in culture. At every stage of life, diet affects future development. For example, a program in Guatemala that provided adequate nutrition to pregnant women and children under age 3 had benefits for emerging adults 20 years later—

set point A particular body weight that an individual’s homeostatic processes strive to maintain.

For body weight, there is a homeostatic set point, or settling point, that makes people eat when hungry and stop eating when full. Of course, extreme dieting may alter the set point: Eating disorders such as anorexia and bulimia nervosa may worsen in early adulthood, and death from such disorders is more likely in the 20s than in the teens. Or people may routinely overeat, again shortening their life span. [Lifespan Link: Eating disorders were discussed in detail in Chapter 14.]

body mass index (BMI) The ratio of a person’s weight in kilograms divided by his or her height in meters squared.

The body mass index (BMI)—the ratio between weight and height (see Table 17.2)—is used to determine whether a person is below, at, or above normal weight. A BMI below 18 is a symptom of anorexia, between 20 and 25 indicates a normal weight, above 25 is considered overweight, and 30 or more is called obese. Emerging adulthood correlates with healthy weight.

| To find your BMI, locate your height in the first column; then look across that row. Your BMI appears at the top of the column that contains your weight. | ||||||||||||||

| BMI | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 35 | 40 |

| Height (in feet and inches) | Weight (in pounds) | |||||||||||||

| 4′10″ | 91 | 96 | 100 | 105 | 110 | 115 | 119 | 124 | 129 | 134 | 138 | 143 | 167 | 191 |

| 4′11″ | 94 | 99 | 104 | 109 | 114 | 119 | 124 | 128 | 133 | 138 | 143 | 148 | 173 | 198 |

| 5′0″ | 97 | 102 | 107 | 112 | 118 | 123 | 128 | 133 | 138 | 143 | 148 | 153 | 179 | 204 |

| 5′1″ | 100 | 106 | 111 | 116 | 122 | 127 | 132 | 137 | 143 | 148 | 153 | 158 | 185 | 211 |

| 5′2″ | 104 | 109 | 115 | 120 | 126 | 131 | 136 | 142 | 147 | 153 | 158 | 164 | 191 | 218 |

| 5′3″ | 107 | 113 | 118 | 124 | 130 | 135 | 141 | 146 | 152 | 158 | 163 | 169 | 197 | 225 |

| 5′4″ | 110 | 116 | 122 | 128 | 134 | 140 | 145 | 151 | 157 | 163 | 169 | 174 | 204 | 232 |

| 5′5″ | 114 | 120 | 126 | 132 | 138 | 144 | 150 | 156 | 162 | 168 | 174 | 180 | 210 | 240 |

| 5′6″ | 118 | 124 | 130 | 136 | 142 | 148 | 155 | 161 | 167 | 173 | 179 | 186 | 216 | 247 |

| 5′7″ | 121 | 127 | 134 | 140 | 146 | 153 | 159 | 166 | 172 | 178 | 185 | 191 | 223 | 255 |

| 5′8″ | 125 | 131 | 138 | 144 | 151 | 158 | 164 | 171 | 177 | 183 | 190 | 197 | 230 | 262 |

| 5′9″ | 128 | 135 | 142 | 149 | 155 | 162 | 169 | 176 | 182 | 189 | 196 | 203 | 236 | 270 |

| 5′10″ | 132 | 139 | 146 | 153 | 160 | 167 | 174 | 181 | 188 | 195 | 202 | 207 | 243 | 278 |

| 5′11″ | 136 | 143 | 150 | 157 | 165 | 172 | 179 | 186 | 193 | 200 | 208 | 215 | 250 | 286 |

| 6′0″ | 140 | 147 | 154 | 162 | 169 | 177 | 184 | 191 | 199 | 206 | 213 | 221 | 258 | 294 |

| 6′1″ | 144 | 151 | 159 | 166 | 174 | 182 | 189 | 197 | 204 | 212 | 219 | 227 | 265 | 302 |

| 6′2″ | 148 | 155 | 163 | 171 | 179 | 186 | 194 | 202 | 210 | 218 | 225 | 233 | 272 | 311 |

| 6′3″ | 152 | 160 | 168 | 176 | 184 | 192 | 200 | 208 | 216 | 224 | 232 | 240 | 279 | 319 |

| 6′4″ | 156 | 164 | 172 | 180 | 189 | 197 | 205 | 213 | 221 | 230 | 238 | 246 | 287 | 328 |

| Normal | Overweight | Obese | ||||||||||||

| Source: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. | ||||||||||||||

About half of all emerging U.S. adults are within the normal BMI range, as are less than one-

Once emerging adults become independent, they can change childhood eating patterns. Sometimes they do. As a generation, U.S. young adults consume more bottled water, organic foods, and nonmeat diets than do older adults, and many become more fit than their parents were at the same age. A large British study found that about one-

A study in the United States found that emerging adults who lived on college campuses ate a more balanced, healthier diet than those living with their parents (Laska et al., 2010). The effect of home cooking continues, however, no matter where the person lives: The strongest influence on fruit and vegetable consumption in emerging adulthood is family patterns at home during childhood (Larson et al., 2012).

Obviously, better eating is not automatic. Although some emerging adults lose excess weight, others gain. According to the British study cited above, 12 percent of normal-

Particular nutritional hazards await young adults who are immigrants or children of immigrants. If they decide to “eat American,” they might avoid curry, hot peppers, or wasabi—

No matter what their ancestry, today’s emerging adults are fatter than past cohorts, and as they age they gain weight—

SUMMING UP

Emerging adulthood is a distinct period of life, often defined as between ages 18 and 25, when most people are strong, healthy, and attractive. They have well-