Psychopathology

Psychopathology

Most emerging adults enjoy the freedom that modern life has given them. Not all do, however. Although physical health peaks during these years, with almost no new, serious diseases, the same is not true for psychological health. Average well-

Multiple Stresses of Emerging Adults

Except for dementia, emerging adults experience more of every diagnosed psychological disorder (sometimes called mental illness) than any older group. Their rate of serious mental illness is almost double that of adults over age 25 (SAMHSA, 2009). Most serious disorders start in adolescence and emerging adulthood, and most are comorbid and untreated. That means, for instance, that an overly anxious young adult is also likely to be depressed (comorbid) and to have no professional help for either disorder (untreated) (Wittchen, 2012).

The first signs of future illness often appear in childhood, and symptoms typically worsen in adolescence. However, the full disorder often becomes evident and thus diagnosed for the first time during adulthood. This was one conclusion from research on psychological disorders in people in 14 nations (Kessler et al., 2012).

The burden falls not only on individuals and their families, but on societies as well. Although “mental disorders cause fewer deaths than infectious diseases, they cause as much or more disability because they strike early and can last a long time” (G. Miller, January 2006, p. 459).

Why does an increase take place in emerging adulthood? One reason may be the sexual freedom just described, which sometimes causes anxiety, depression, and disease. In addition, parents are less involved in the day-

Most people can withstand uncertainly in one domain of their lives, but many emerging adults are hit from several directions. Multiple identity crises are likely to cause depression and anxiety (Crocetti et al., 2012). Vocational, financial, educational, and interpersonal stresses may combine during these years because

for the first time in their lives, young adults are faced with independence and its inherent rights and responsibilities. Given the novelty of these challenges, young adults may lack the requisite skills to effectively cope and subsequently experience negative mental health outcomes, including depression and anxiety.

[Cronce & Corbin, 2010, p. 92]

diathesis-

Most psychologists and psychiatrists accept the diathesis—

College counselors report an increasing number of students with serious psychological problems (Sander, 2013). This is particularly true for students at small, private, four-

Strength in any one domain of an emerging adult’s life is protective; the combination of stressors causes the breakdown. Certainly family context has an effect, for better or worse. Having a job may be pivotal, at least according to results from a program to secure employment for adolescents, young adults, and older adults with serious mental disorders. Benefits were particularly apparent for the emerging adults (Burke-

Thus, the demands of emerging adulthood may cause psychopathology when added to preexisting vulnerability. As a result, many disorders appear: Some (e.g., anorexia and bulimia) we have already discussed, and others (extreme risk-

Mood Disorders

Before they reach age 30, 8 percent of U.S. residents suffer from a mood disorder: mania, bipolar disorder, or severe depression. Mood disorders often appear, disappear, and reappear—

The most common mood disorder is major depressive disorder, signaled by a loss of interest or lack of pleasure in nearly all activities for two weeks or more. Other difficulties—

Major depression may be rooted in biochemistry, specifically in neurotransmitters and hormones. However, as the diathesis–

Women at all ages are more often depressed than men, but according to research on thousands of young adults in 15 nations, men are particularly vulnerable to depression from loss of a romantic partner. Marriage typically relieves male depression, but divorce may plummet men into despair (Scott et al., 2009; Seedat et al., 2009). However, day-

Depression may be debilitating in emerging adulthood because it undercuts accomplishments—

Failure to get treatment for depression is common among emerging adults (Zarate, 2010). They distance themselves from anyone who might know them well enough to realize that professional help is needed. Furthermore, depressed people of all ages characteristically believe that nothing will help. For that reason, although effective treatment lifts most depression, sufferers are unlikely to seek it on their own.

Anxiety Disorders

Another major set of disorders, evident in one-

Anxiety disorders are even more prevalent than depression. This is true worldwide, according to the World Mental Health surveys of the World Health Organization (Kessler et al., 2009). Incidence statistics vary from study to study, depending partly on definition and cutoff score, but all research finds that many emerging adults are anxious about themselves, their relationships, and their future.

Age and genetic vulnerability shape the symptoms of anxiety disorders. For instance, everyone with PTSD has had a frightening experience—

Similarly, every anxiety disorder is affected by culture and context. In the United States, social phobia—

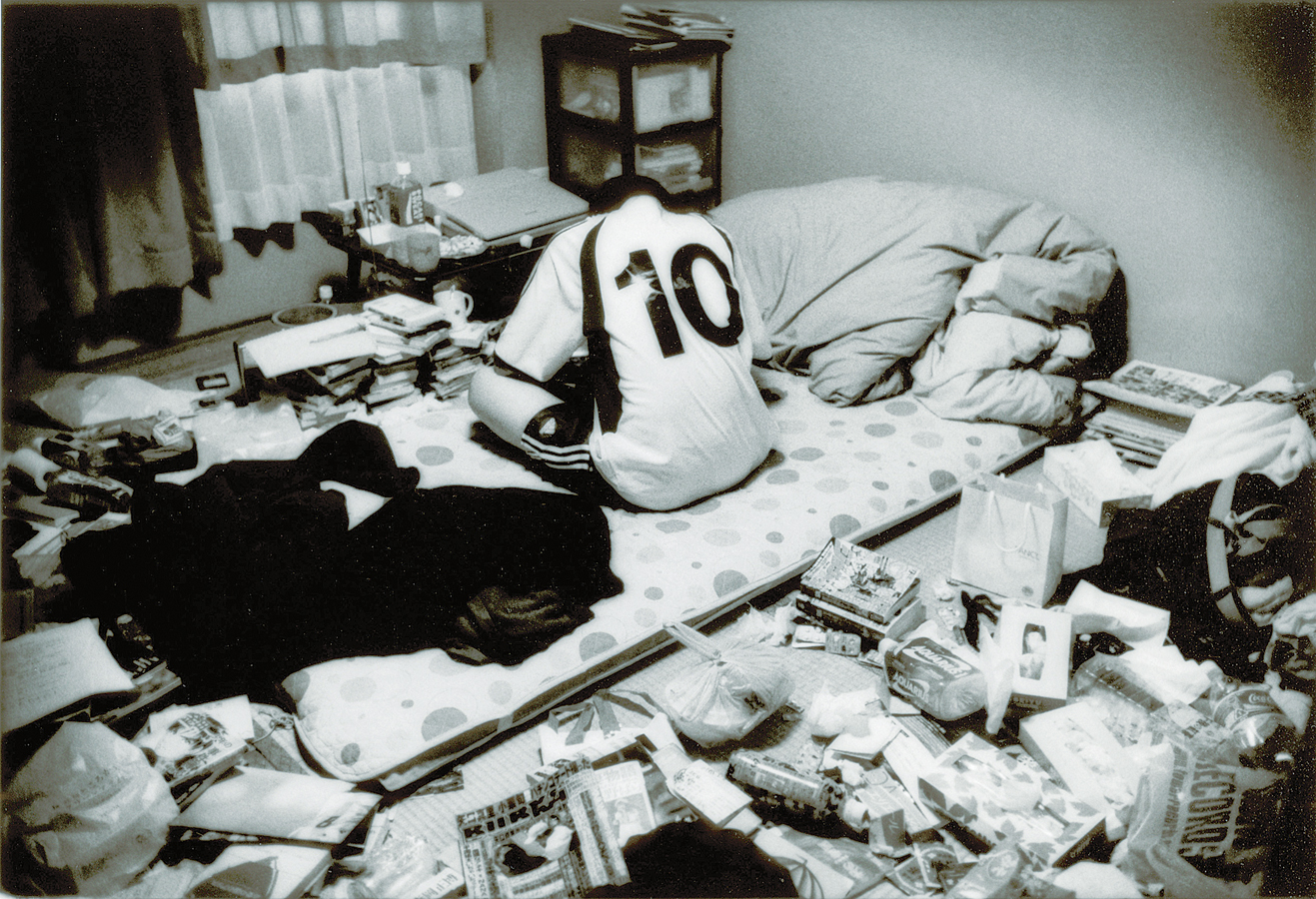

hikikomori A Japanese word literally meaning “pull away”; it is the name of an anxiety disorder common among young adults in Japan. Sufferers isolate themselves from the outside world by staying inside their homes for months or even years at a time.

In Japan, a severe social phobia has appeared that may affect more than 100,000 young adults. It is called hikikomori, or “pull away” (Teo, 2010). The hikikomori sufferer stays in his (or, less often, her) room almost all the time for six months or more, a reaction to extreme anxiety about the social and academic pressures of high school and college. The close connection between Japanese mothers and children—

It is easier to see how a culture in a distant nation (Japan) enables a particular anxiety disorder (hikikomori) than it is to recognize how one’s own culture raises anxiety in emerging adults. However, the severe anxiety about food and weight that underlies eating disorders seems more common in the United States than elsewhere. Anxiety seems to rise in emerging adulthood everywhere. Symptoms vary, but the emotion is universal.

Schizophrenia

About 1 percent of all adults experience schizophrenia, becoming overwhelmed by disorganized and bizarre thoughts, delusions, hallucinations, and emotions (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Schizophrenia is found in every nation, but some cultures and contexts have much higher rates than others (Anjum et al., 2010).

No doubt the cause of schizophrenia is partly genetic, although most people with this disorder have no immediate family members diagnosed with it. Beyond genetics, several other risk factors are known (McGrath & Murray, 2011). One is malnutrition when the brain is developing: Women who are severely malnourished in the early months of pregnancy are twice as likely to have a child with schizophrenia.

Another is extensive social pressure. Schizophrenia is higher among immigrants than among their relatives who stayed in the home country, and the rate triples when young immigrant adults have no familial supports (Bourque et al., 2011). Drug use also increases the risk, another reason the incidence peaks in emerging adulthood, since during these years many people try psychoactive drugs.

Especially for Immigrants What can you do in your adopted country to avoid or relieve the psychological stresses of immigration?

Response for Immigrants: Maintain your social supports. Ideally, emigrate with members of your close family, and join a religious or cultural community where you will find emotional understanding.

The first symptoms of schizophrenia typically begin in adolescence. Diagnosis is most common from ages 18 to 24, with men particularly vulnerable. Men who have had no symptoms by age 35 almost never develop schizophrenia. Women who develop schizophrenia are also usually young adults, but some older women are diagnosed as well (Anjum et al., 2010).

This raises the question: Does something in the body, mind, or social surroundings trigger schizophrenia in emerging adults? The diathesis–

SUMMING UP

Most emerging adults enjoy their independence. However, those with inborn vulnerability, and with added emotional and cognitive burdens, may experience a serious disorder during emerging adulthood. Mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and schizophrenia are all diagnosed more often before age 25 than later, partly because the stresses of this period occur when family supports are less available.