Taking Risks

Taking Risks

Many emerging adults bravely, or foolishly, risk their lives. Extreme risk-

Destructive risks are numerous, including having sex without a condom, driving without a seat belt, carrying a loaded gun, and abusing drugs. The attraction of an adrenaline rush is one reason people commit crimes or gamble (Cosgrave, 2010). The worst results of risk-

The reasons for such risk-

Observation Quiz One detail in the young man’s hands suggests that he is taking a risk in Asia, not North America. What is it?

Answer to Observation Quiz: The cigarette (not the camera). Most young men in Canada and the United States do not smoke, especially publicly and casually, as this man does.

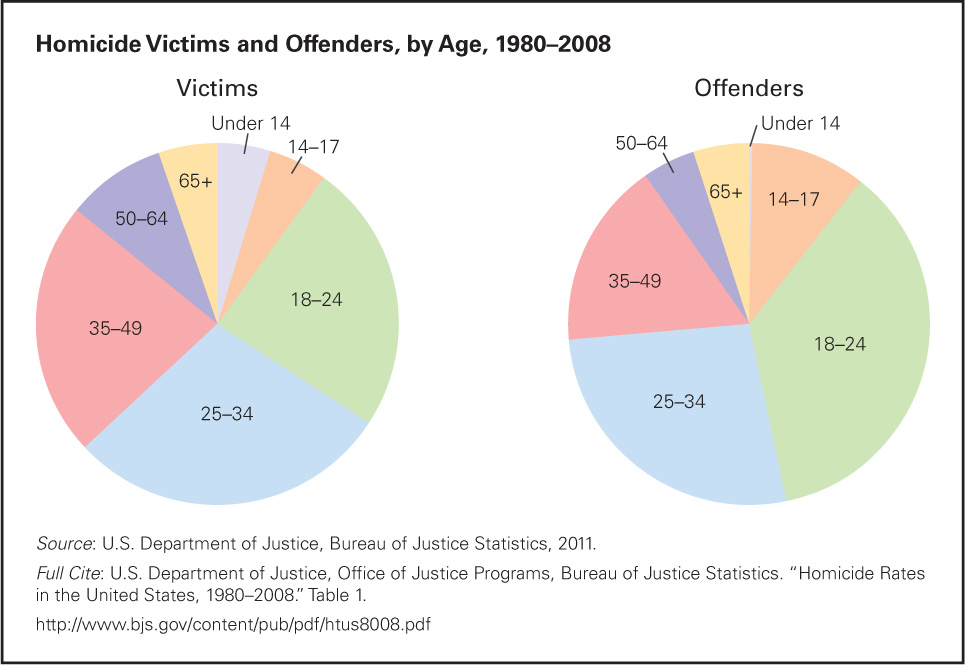

The social reason is that young men vie for status among other males and for female attention by showing off and destroying other young men, sometimes figuratively and sometimes literally. It seems hard for them to react to an insult from another man, or even an accidental push, by walking away. That is one explanation for the statistics about homicide, since both the victim and the perpetrator are usually emerging adult males (see Figure 17.2). Increased competition for mates may be the reason that the violent death rate of emerging adults in China seems to be increasing, an unexpected consequence of the one-

FIGURE 17.2

Seven Serious Years It may seem as if two adult groups include almost as many offenders and victims as the green emerging adult group, but notice the age span. The adult groups are ten and fifteen years. A person is more than twice as likely to be raped, murdered, or seriously wounded (usually by an emerging adult) at age 20 than age 40).Full Cite: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. “Homicide Rates in the United States, 1980–

extreme sports Forms of recreation that include apparent risk of injury or death and that are attractive and thrilling as a result. Motocross is one example.

The biological reason is that young men’s hormones, energy, and brain development, which once propelled them to engage in strenuous physical work, now need another outlet. The most popular outlets are sports such as football, wrestling, and the newer extreme sports. One example of an extreme sport is freestyle motocross—riding a motorcycle off a ramp, catching “big air,” doing tricks while falling, and hoping to land upright.

Many young adults are fans or participants of extreme sports; they find golf, bowling, and so on too tame (Breivik, 2010). As the authors of one study of dirtbikers (off-

The conclusion that risk-

For people, think about this example. A 22-

“Major crashes” are part of every sport Pastrana likes. Four years later, in 2010, he set a new record for leaping through big air in an automobile, speeding off a ramp on the California shore and over the ocean, to a barge more than 250 feet out. He crashed into a barrier on the boat, emerging, ecstatic and unhurt, to the thunderous cheers of thousands of other young adults (Roberts, 2010).

In 2011, a broken ankle temporarily stopped him, but soon he was back risking his life to the acclaim of his cohort, winning races rife with flips and other hazards. In 2013, after some more serious injuries, he said he was “still a couple of surgeries away” from being able to race on a motorcycle, but he decided to race at NASCAR. (But see caption on the left.)

Pastrana is far from the only one attracted to extreme sports. These events attract thousands of adults, who travel long distances and spend large sums of money to jump off famous bridges (base jumping, with parachute), climb the sheer or icy sides of mountains, ride dangerous waves (on a surf board or body surfing), and so on. Such adventure has become a significant niche of tourism (Allman et al., 2009).

Drug Abuse

Although risk-

drug abuse The ingestion of a drug to the extent that it impairs the user’s biological or psychological well-

Drug abuse occurs whenever a person uses a drug that is harmful to physical, cognitive, or psychosocial well-

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

Brave or Foolish?

As you might guess, I am not a fan of extreme sports; I find them not only dangerous but also irrational. Many adults, especially women like me, find young adult risk-

Societies as well as individuals benefit precisely because emerging adults take chances. Enrolling in college, moving to a new state or nation, getting married, having a baby—

Many occupations are filled with risk-

Extreme sports may seem irrational from a distance, but not for the participant. One study found that facing fear was exhilarating and transformative, improving the individual’s self-

Consider again the developmental need to experiment and explore. We would all suffer if young adults were always timid, traditional, and afraid of innovation. They need to befriend strangers, try new foods, explore ideas, travel abroad, and sometimes risk their lives.

Whenever I find myself critical of something that millions of other people admire, I wonder if my perspective is too narrow, too culture-

But just because I don’t want to ride into big air, or even watch a game in which men in helmets tackle each other, does not mean that I should criticize those who do. Super Bowl Sunday attracts more TV viewers than any other show, and advertisers spend 4 million dollars for a 30-

PREDRAG VUCKOVIC/RED BULL VIA GETTY IMAGES

drug addiction A condition of drug dependence in which the absence of the given drug in the individual’s system produces a drive—

Drug abuse can lead to drug addiction, a condition of dependence in which the absence of a drug causes intense cravings to satisfy a need. The need may be either physical (e.g., to stop the shakes, settle one’s stomach, or sleep) or psychological (e.g., to quiet anxiety or lift depression). Withdrawal symptoms are the telltale signs of addiction.

Although cigarettes and alcohol can be as addictive and destructive as illegal drugs, from an emerging-

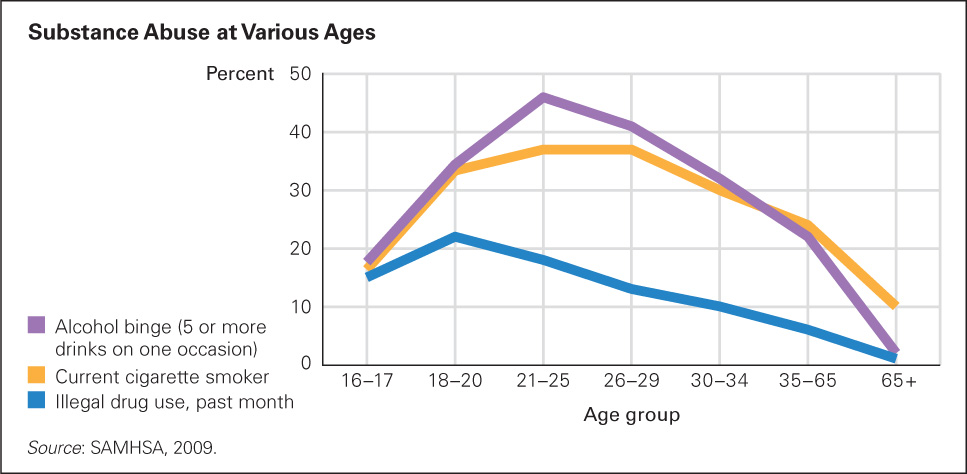

FIGURE 17.3

Too Old for That As you can see, emerging adults are the biggest substance abusers, but illegal drug use drops much faster than cigarette smoking or binge drinking. This graph depicts drug use at one time in one nation (the United States in 2008), but these trends are universal.It may be surprising, however, that drug abuse—

Being with peers, especially for college men, seems to encourage many kinds of drug abuse. The opposite is also true. In fact, the emerging adults least likely to abuse drugs are women who are not in college, living with their parents. Patterns of use, abuse, and addiction are also affected by historical trends; they vary from time to time and from nation to nation. However, the overall trend is curvilinear everywhere, rising during emerging adulthood and then falling with maturity.

Especially for Substance Abuse Counselors Can you think of three possible explanations for the more precipitous drop in the use of illegal drugs compared to legal ones?

Response for Substance Abuse Counselors: Legal drugs could be more addictive, or the thrill of illegality may diminish with age, or the fear of arrest may increase. In any case, treatment for young-

With drugs as with many other risks, the immediate benefits obscure the eventual costs. Most young adults use alcohol to reduce social anxiety—

Indeed, no matter what the drug, crossing the line between use and abuse does not always ring alarms in the user. This was apparent in a study of ketamine use among young adults in England, who justified its use—

Although family members often try to stop drug abuse, intervention is least likely during emerging adulthood. During these years, parents keep their distance and drug users are unlikely to marry, so abuse can continue unchecked for years.

Yet longitudinal data show that early drug abuse impairs later life in many ways. Those who use drugs heavily in high school are less likely to go to college, and those who begin heavy drug use in college are less likely to earn a degree, find a good job, or sustain a romance (Johnston et al., 2009). Drug abuse during early adulthood may lead to serious physical and mental ailments later in life. Longitudinal research comes to this conclusion in every nation. For instance, a 21-

Social Norms

One discovery from the study of human development that might help the health of emerging adults is the power of social norms, which are customs for usual behavior within a particular society. Social norms exert a particularly strong influence on college students. They want the approval of their new peers; social norms matter.

Some social norms work well for emerging adults. This is evident from rates of obesity, since young adults watch their weight in order to be attractive to others, and from rates of exercise, since young adults join sports teams and gyms partly because norms encourage it. However, some norms push emerging adults in destructive directions.

Base Rate Neglect

In Chapter 15 you read about the logical error that humans often make called base rate neglect—

An example from college students is that they notice the flashy, noisy, unusual classmate, and might mistakenly assume such behavior is far more typical than it is. You probably have noticed such prejudice in other people, who judge everyone of a certain ethnic or national background because of what one member of that group has done. In the same ways, base rate neglect and availability error may lead to risk-

Emerging adults are immersed in social settings (colleges, parties, concerts, sports events) where risk-

For instance, in one experiment, several small groups of college students were offered as much alcohol as they wanted while they socialized with one another. In some groups, one student was secretly recruited in advance to drink heavily; in others, one student was assigned to drink very little; in a third condition, there was no student confederate. In those groups with a designated drinker, participants followed the norm set by the heavy drinker, increasing the average amount of alcohol they consumed, but their drinking was unaffected by the light drinker (reported in W. R. Miller & Carroll, 2006).

The power of social norms as well as the “liquid courage” of alcohol is evident at concerts and sports events when a crowd of people suddenly moves so quickly that some are crushed and trampled, or when a new extreme sport becomes popular. For instance, a small group of young-

A similar story holds for other extreme sports—

Norms and Drugs

social norms approach A method of reducing risky behavior that uses emerging adults’ desire to follow social norms by making them aware, through the use of surveys, of the prevalence of various behaviors within their peer group.

An understanding of the perceptions and needs of emerging adults, as well as the realization that college students abuse drugs even more than others their age, has led to a promising effort to reduce alcohol abuse on college campuses. This is the social norms approach, using surveys to make students aware of the true prevalence of various behaviors.

About half the colleges in the United States have surveyed alcohol use on their campuses and reported the results. Almost always, students not only overestimate how much the average student drinks, but they also underestimate how their peers feel about the loud, late talking and other behaviors of drunk students (C. M. Lee et al., 2010). Ironically, those who exaggerate the quantity of drinking are often those who are relatively isolated and depressed. They then drink to be like everyone else, and they only become more depressed.

In general, when survey results are reported and college students realize that most of their classmates study hard, avoid binge drinking, refuse drugs, and are sexually abstinent, faithful, or protected, they are more likely to follow these social norms. This is especially true if the survey is conducted and reported on the Web (not a paper questionnaire with written responses) and if the students are not living with many heavy drinkers (Ward & Gryczynski, 2009). In the latter case, the social norm of their immediate residence may be more powerful than information about students overall.

Recent research continues to find that emerging adults are influenced by perceived norms, including not only how much people drink but also by what the negative consequences might be. The relationship is not always simple—

An interesting caveat is that when people are drinking and using drugs with other people who are drinking and using drugs, they tend to perceive the positive effects more than the negative ones (Brie et al., 2011). They do not realize that they are keeping others awake; they do not know that someone who has passed out may need medical attention; they think they can drive, or think, or walk when they cannot. That may explain why people who are trying to stop a habit need to avoid people and contexts that might encourage the habit they want to break. [Lifespan Link: The challenges of breaking a habit are discussed in A View from Science, Chapter 20.]

Implications of Risks and Norms

One of my older students, John, told the class about his experience as an emerging adult. At first, he spoke with amused pride. But by the end of his narrative, he was troubled, partly because John was now the father of a little boy he adored, and he realized that his son might become an equally reckless young man.

John told us that, during a vacation break in his first year of college, he and two of his male friends were sitting, bored, on a beach. One friend proposed swimming to an island, which was barely visible on the horizon. They immediately set out. After swimming for a long time, John realized that he was only about one-

What does this episode signify about the biosocial development of emerging adults? It is easy to understand why John started swimming. Male ego, camaraderie, boredom, and the overall context made this an attractive adventure. Young men like to be active, feeling their strong arms, legs, and lungs.

Like John, many adults fondly remember past risks. They forget the friends who caught STIs, who had abortions or unwanted births, who became addicts or alcoholics, or who died young; they ignore the fact that their younger siblings and children might do the same. Emerging adulthood is a strong and healthy age, but not without serious risks. Why swim to a distant island? More thinking is needed, as described in the next chapter.

SUMMING UP

Risk-

In general, males take more risks than females; admiration from peers of both sexes may be part of the motivation. Emerging adults—