Morals and Religion

Morals and Religion

As already explained in earlier chapters, the process of developing morals begins in childhood. Children combine the values of their parents, their culture, and their peers with their own sensibilities as they mature. However, that is only the beginning. Many researchers believe that adult responsibilities, experiences, and education are crucial in shaping a person’s ethics. The idea that emerging adulthood is pivotal for a process that continues through middle age has been supported by research over the past decades. As one expert said:

Dramatic and extensive changes occur in young adulthood (the 20s and 30s) in the basic problem-

[Rest, 1993, p. 201]

This expert has found that college education is one stimulus for young adults’ shifts in moral reasoning, especially if coursework includes extensive discussion of moral issues or if the student’s future profession (such as law or medicine) requires ethical decisions. Even without college, another researcher finds that people in early adolescence are least likely to make moral decisions and that the incidence of moral decision making rises as people mature and confront various issues (Nucci & Turiel, 2009).

There is a paradoxical connection between attending religious services, which becomes less frequent during emerging adulthood, and developing religious convictions, which becomes more frequent (Barry et al., 2012). Emerging adults are interested in developing prosocial values, but they are less interested in hearing a religious leader express the received wisdom of their faith.

DAN KITWOOD/GETTY IMAGES

Which Era? What Place?

As discussed in earlier chapters, moral values are powerfully affected by circumstances, including national background, culture, and era.

The power of culture makes it difficult to assess how adult morality changes with age because changing opinions can be judged as improvements or declines. For example, compared to younger adults in the United States, older people tend to be less supportive of gay marriage and more troubled by divorce and yet more supportive of public money for mass transit and health.

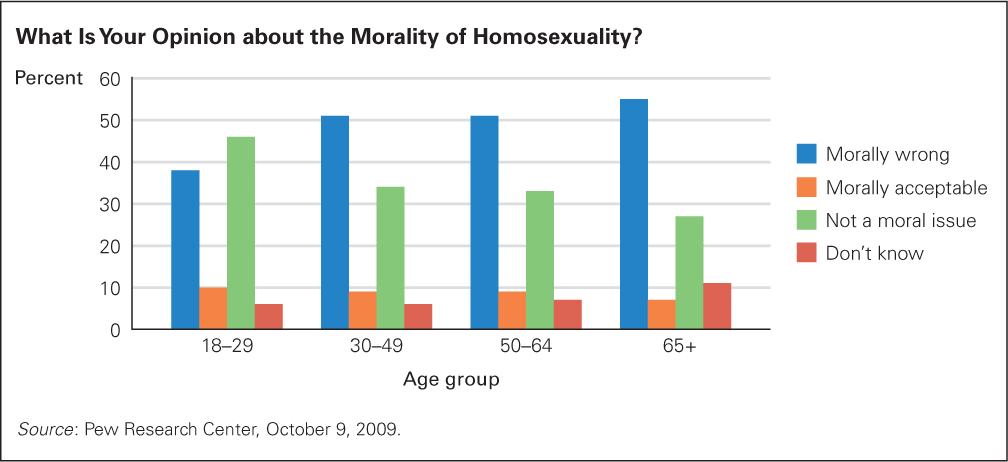

Do these age trends suggest that adults become more or less moral? Or are older people more stuck in their ways, using morality to justify their intransigence instead of shifting when popular opinion and practice cause others to rethink their moral position? Indeed, more older than younger people think that various issues are moral ones, a position that allows them to stick to an outmoded opinion “on moral grounds.” Is that intransigence, or is that integrity? (See Figure 18.2.)

FIGURE 18.2

Don’t Judge Me On many issues, not only this one, older adults are more likely to judge something as right or wrong than are younger adults. Your own judgment may reflect your age and personal experience more than anything else. The specifics on this is issue keeps changing, with far fewer people of every age thinking homosexuality is morally wrong, but at every age on almost every issue, older adults see more moral issues than younger ones do.Despite such concerns, the research does indicate that the process (though not necessarily the outcome) of moral thinking improves with age. At least adult thinking may be more flexible than adolescent thinking. As one scholar explains it, “The evolved human brain has provided humans with cognitive capacity that is so flexible and creative that every conceivable moral principle generates opposition and counter principles” (Kendler, 2002, p. 503).

Evidence for moral growth abounds in biographical and autobiographical literature. Most readers of this book probably know someone (or might be that someone) who had a narrow, shallow outlook on the world at age 18 and then developed a broader, deeper perspective and empathy between adolescence and adulthood (Eisenberg et al., 2005).

Many people would consider more open, dialectical, and flexible thinking (as in the postformal thinking just described) to also be more ethical. A study of the relationship between postformal thinking and concepts of God found that a more complex, multifaceted concept correlated with more postformal thought (Benovenli et al., 2011).

Dilemmas for Emerging Adults

It is fortunate that adolescent egocentrism ebbs because emerging adults often experience dilemmas that raise moral issues that egocentrism would interfere with resolving. Most adults are no longer bound by their parents’ rules or by their childhood culture, but they are not yet connected to a family of their own. As a result, they must decide for themselves what to do about sex, drugs, education, vocation, and many other matters.

Gender Differences

morality of care In Gilligan’s view, moral principles that reflect the tendency of females to be reluctant to judge right and wrong in absolute terms because they are socialized to be nurturing, compassionate, and nonjudgmental.

morality of justice In Gilligan’s view, moral principles that reflect the tendency of males to emphasize justice over compassion, judging right and wrong in absolute terms.

There is widespread disagreement about whether gender differences in morality exist. Carol Gilligan, a Harvard professor who challenged some of Kohlberg’s work, believes that decisions about reproduction advance moral thinking, especially for women (Gilligan, 1981; Gilligan et al., 1990). According to Gilligan, the two sexes think differently about parenthood, abortion, and so on. Girls are raised to develop a morality of care. They give human needs and relationships the highest priority. In contrast, boys develop a morality of justice; they are taught to distinguish right from wrong.

No other research has found gender differences in moral thinking. Factors such as education, specific dilemmas (some situations evoke care and some justice), and culture correlate more strongly than gender with whether a person’s moral judgments emphasize relationships or absolutes (Juujärvi, 2005; Vikan et al., 2005; Walker, 1984).

For example, a longitudinal study of high school students who were exceptionally talented in math found that, as adults, the men were more likely to have advanced degrees in science and math and to be leaders in various fields of science, whereas many of the equally talented women had chosen to devote more time to their families (Ferriman et al., 2009). Is that a moral difference, a cultural pattern, or a gender difference?

Measuring Moral Growth

How can we assess whether a person uses postformal thinking regarding moral choices? In Kohlberg’s scheme, people discuss standard moral dilemmas, responding to various probes. Over decades of longitudinal research, Kohlberg noted that during young adulthood, some respondents seemed to regress from postconventional to conventional thought. On further analysis of the responses, this shift could be an advance because the young adults incorporated human social concerns (Labouvie-

Defining Issues Test (DIT) A series of questions developed by James Rest and designed to assess respondents’ level of moral development by having them rank possible solutions to moral dilemmas.

The Defining Issues Test (DIT) is another way to measure moral thinking. The DIT presents a series of questions with specific choices. For example, in one DIT dilemma, a news reporter must decide whether to publish some old personal information that will damage a political candidate. Respondents rank their priorities from personal benefits (“credit for investigative reporting”) to higher goals (“serving society”).

In the DIT, the ranking of items leads to a number score, which correlates with other aspects of adult cognition, experience, and life satisfaction (Schiller, 1998). These correlations suggest that people who are more caring about other people are also more satisfied with their lives, but of course correlations are provocative, not proof. In general, DIT scores rise with age because adults gradually become less doctrinaire and self-

A study of adolescents and young adults in the Netherlands found intriguing results when they were given the DIT (Raaijmakers, 2005). Although many individual differences were found, some age trends were apparent: The responses of the participants shifted from justification for past behavior (adolescents) to guidance for future behavior (emerging adults). DIT scores gradually rose among adolescents who rarely broke the law. However, for delinquents, DIT scores rose as they grew older but preceded a drop in delinquency. For emerging adults, then, moral thinking may produce moral behavior, not just vice versa.

Many critics, however, complain that the DIT measures only some parts of moral development (Hannah et al., 2011). Factors such as religious conviction, postformal thought, moral courage, and social support are crucial in moral decisions. The problem, of course, is that it is difficult to measure all these factors, especially because one person’s moral choice may be the opposite of another’s. The same problem appears with faith development, as you will now see.

Stages of Faith

Spiritual struggles—

To describe this process, James Fowler (1981, 1986) developed a now-

- Stage 1: Intuitive-

projective faith . Faith is magical, illogical, imaginative, and filled with fantasy, especially about the power of God and the mysteries of birth and death. It is typical of children ages 3 to 7. - Stage 2: Mythic-

literal faith . Individuals take the myths and stories of religion literally, believing simplistically in the power of symbols. God is seen as rewarding those who follow divine laws and punishing others. Stage 2 is typical from ages 7 to 11, but it also characterizes some adults. Fowler cites a woman who says extra prayers at every opportunity, to put them “in the bank.” - Stage 3: Synthetic-

conventional faith . This is a conformist stage. Faith is conventional, reflecting concern about other people and favoring “what feels right” over what makes intellectual sense. Fowler quotes a man whose personal rules include “being truthful with my family. Not trying to cheat them out of anything…. I’m not saying that God or anybody else set my rules. I really don’t know. It’s what I feel is right.” - Stage 4: Individual-

reflective faith . Faith is characterized by intellectual detachment from the values of the culture and from the approval of other people. College may be a springboard to stage 4, as the young person learns to question the authority of parents, teachers, and other powerful figures and to rely instead on his or her own understanding of the world. Faith becomes an active commitment. - Stage 5: Conjunctive faith. Faith incorporates both powerful emotional ideas (such as the power of prayer and the love of God) and rational conscious values (such as the worth of life compared with that of property). People are willing to accept contradictions, obviously a postformal manner of thinking. Fowler says that this cosmic perspective is seldom achieved before middle age.

- Stage 6: Universalizing faith. People at this stage have a powerful vision of universal compassion, justice, and love that compels them to live their lives in a way that others may think is either saintly or foolish. A transforming experience is often the gateway to stage 6, as happened to Moses, Muhammad, the Buddha, and Paul of Tarsus, as well as more recently to Mohandas Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., and Mother Teresa. Stage 6 is rarely achieved.

If Fowler is correct, faith, like other aspects of cognition, progresses from a simple, self-

SUMMING UP

Moral issues challenge cognitive processes as people move beyond the acceptance of authority (typical in childhood) and past reactive rebellion (characteristic of adolescents). Cultural values always shape beliefs; whether women’s traditional emphasis on relationships and men’s traditional emphasis on absolutes are the result of sex (biological) or gender (cultural) is not certain. Age and cultural differences are more evident than male/female differences.

Some people become more open and reflective, and less self-