Cognitive Growth and Higher Education

Cognitive Growth and Higher Education

Many readers of this textbook have a personal interest in the final topic of this chapter, the relationship between college education and cognition. All the evidence is positive: College graduates are not only healthier and wealthier than other adults, on average, but also deeper and more flexible thinkers. These conclusions are so powerful that scientists wonder if selection effects or historical trends, rather than college education itself, lead to such encouraging correlations. Let us look at the data.

The Effects of College

AP PHOTO/STEPHAN SAVOIA

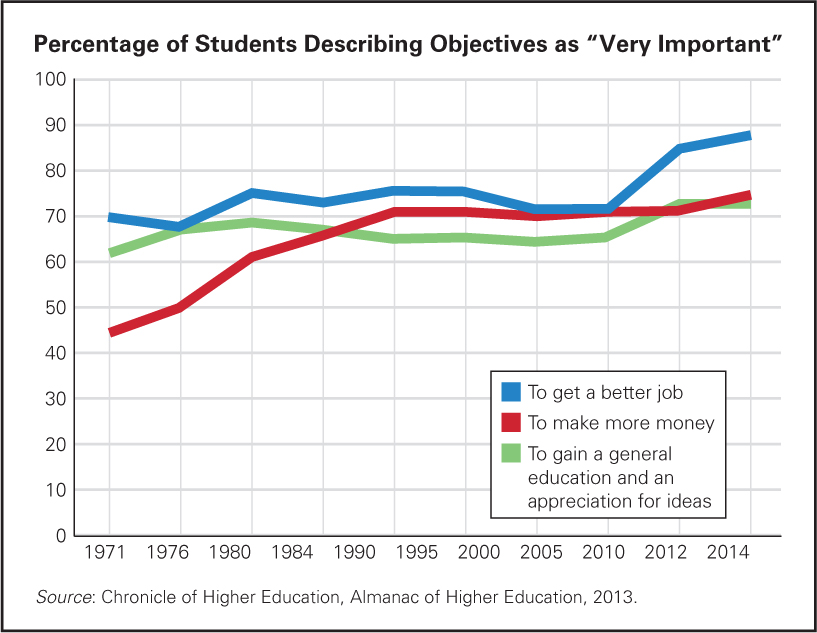

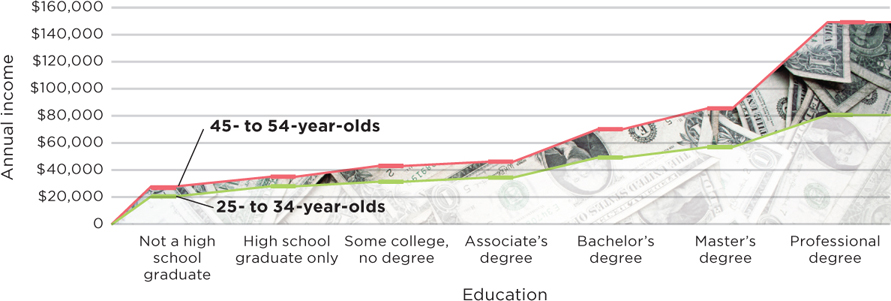

Contemporary students attend college primarily to secure better jobs and to learn specific skills (especially in knowledge and service industries, such as information technology, global business, and health care). Among the “very important” reasons students in the United States enroll in college are “to get a better job” (88 percent) and to make more money (75 percent) (see Figure 18.3).

FIGURE 18.3

Cohort Shift Decades before this study was done, students thought new ideas and a philosophy of life were prime reasons to go to college—Gaining a general education and an appreciation of ideas is a secondary goal; this is “very important” to most students (73 percent) but clearly not as important as the financial goals (Pryor et al., 2012). This is true not only in the United States, but also in many other nations (Jongbloed et al., 1999).

One of my 18-

A higher education provides me with the ability to make adequate money so I can provide for my future. An education also provides me with the ability to be a mature thinker and to attain a better understanding of myself…. An education provides the means for a better job after college, which will support me and allow me to have a stable, comfortable retirement.

[E., personal communication]

Such worries about future costs and retirement may seem premature, but E. is not alone. About 80 percent of students are employed, yet only 20 percent of all students or their parents can pay for college. About two-

College also correlates with better health: College graduates everywhere smoke less, eat better, exercise more, and live longer. They are also more likely to be married, homeowners, and parents of healthy children. Does something gained in college—

Looking specifically at cognitive development, does college make people more likely to combine the subjective and objective in a flexible, dialectical way? Perhaps. College improves verbal and quantitative abilities, adds knowledge of specific subject areas, teaches skills in various professions, and fosters reasoning and reflection. According to one comprehensive review:

Compared to freshmen, seniors have better oral and written communication skills, are better abstract reasoners or critical thinkers, are more skilled at using reason and evidence to address ill-

[Pascarella & Terenzini, 1991, p. 155]

Note that many of these abilities characterize postformal thinking.

Especially for Those Considering Studying Abroad Given the effects of college, would it be better for a student to study abroad in the first year or last year of a college education?

Response for Those Considering Studying Abroad: Since one result of college is that students become more open to other perspectives while developing their commitment to their own values, foreign study might be most beneficial after several years of college. If they study abroad too early, some students might be either too narrowly patriotic (they are not yet open) or too quick to reject everything about their national heritage (they have not yet developed their own commitments).

Some research finds that thinking becomes more reflective and expansive with each year of college. First-

This initial phase is followed by a wholesale questioning of personal and social values, including doubts about the idea of truth itself. If a professor makes an assertion without extensive analysis and evidence, upper-

Finally, as graduation approaches, after considering many ideas, students become committed to certain values, while they realize their opinions might change (Pascarella & Terenzini, 1991; Rest et al., 1999). Facts have become neither gold nor dross, but rather useful steps toward a greater understanding.

According to one classic study (Perry, 1981, 1999), thinking progresses through nine levels of complexity over the four years that lead to a bachelor’s degree, moving from a simplistic either/or dualism (right or wrong, success or failure) to a relativism that recognizes a multiplicity of perspectives (see Table 18.1).

| Dualism modified | Position 1 | Authorities know, and if we work hard, read every word, and learn Right Answers, all will be well. |

| Transition | But what about those Others I hear about? And different opinions? And Uncertainties? Some of our own Authorities disagree with each other or don’t seem to know, and some give us problems instead of Answers. | |

| Position 2 | True Authorities must be Right, the others are frauds. We remain Right. Others must be different and Wrong. Good Authorities give us problems so we can learn to find the Right Answer by our own independent thought. | |

| Transition | But even Good Authorities admit they don’t know all the answers yet! | |

| Position 3 | Then some uncertainties and different opinions are real and legitimate temporarily, even for Authorities.They’re working on them to get to the Truth. | |

| Transition | But there are so many things they don’t know the Answers to! And they won’t for a long time. | |

| Relativism discovered | Position 4a | Where Authorities don’t know the Right Answers, everyone has a right to his own opinion; no one is wrong! |

| Transition | Then what right have They to grade us? About what? | |

| Position 4b | In certain courses, Authorities are not asking for the Right Answer. They want us to think about things in a certain way, supporting opinion with data. That’s what they grade us on. | |

| Position 5 | Then all thinking must be like this, even for Them. Everything is relative but not equally valid. You have to understand how each context works. Theories are not Truth but metaphors to interpret data with. You have to think about your thinking. | |

| Transition | But if everything is relative, am I relative, too? How can I know I’m making the Right Choice? | |

| Position 6 | I see I’m going to have to make my own decisions in an uncertain world with no one to tell me I’m Right. | |

| Transition | I’m lost if I don’t. When I decide on my career (or marriage or values), everything will straighten out. | |

| Commitments in relativism developed | Position 7 | Well, I’ve made my first Commitment! |

| Transition | Why didn’t that settle everything? | |

| Position 8 | I’ve made several commitments. I’ve got to balance them— |

|

| Transition | Things are getting contradictory. I can’t make logical sense out of life’s dilemmas. | |

| Seniors | Position 9 | This is how life will be. I must be wholehearted while tentative, fight for my values yet respect others, believe my deepest values right, yet be ready to learn. I see that I shall be retracing this whole journey over and over— |

| Source: Perry, 1981, 1999. | ||

Perry found that the college experience itself causes this progression: Peers, professors, books, and class discussion all stimulate new questions and thoughts. In general, the more years of higher education and of life experience a person has, the deeper and more dialectical that person’s reasoning becomes (Pascarella & Terenzini, 1991).

Which aspect of college is the primary catalyst for such growth? Is it the challenging academic work, professors’ lectures, peer discussions, the new setting, or living away from home? All are possible. Every scientist finds that social interaction and intellectual challenge advance thinking.

College students expect classes and conversations to further their thinking—

A CASE TO STUDY

College Advancing Thought

One of the leading thinkers in adult cognition is Jan Sinnott, a professor and past editor of the Journal of Adult Development. She describes the first course she taught:

I did not think in a postformal way…. Teaching was good for passing information from the informed to the uninformed…. I decided to create a course in the psychology of aging…with a fellow graduate student. Being compulsive graduate students had paid off in our careers so far, so my colleague and I continued on that path. Articles and books and photocopies began to take over my house. And having found all this information, we seem to have unconsciously sworn to use all of it….

Each class day, my colleague and I would arrive with reams of notes and articles and lecture, lecture, lecture. Rapidly!…The discussion of death and dying came close to the end of the term (naturally). As I gave my usual jam-

[Sinnott, 2008, pp. 54–

Sinnott changed her lesson plan. In the next class, the student told her story.

In the end, the students agreed that this was a class when they…synthesized material and analyzed research and theory critically.

[Sinnott, 2008, p. 56]

Sinnott writes that she still lectures and gives multiple-

Changes in the College Context

You probably noticed that many of the references in the previous pages are decades old. Perry’s study was first published in 1981. His conclusions may no longer apply, especially because both sides of the dialectic—

Changes in the Students

College is no longer for the elite few.

massification The idea that establishing institutions of higher learning and encouraging college enrollment can benefit everyone (the masses).

To improve health and increase productivity, every nation has increased the number of students enrolled in college. This growth in enrollment has led to massification—the idea that college could benefit everyone (the masses) (Altbach et al., 2010). The United States was the first major nation to accept that idea, establishing thousands of institutions of higher learning and boasting millions of college students by the middle of the twentieth century.

The United States no longer leads in massification, however. In some nations, more than half of all 25-

Especially for High School Teachers One of your brightest students doesn’t want to go to college. She would rather keep waitressing in a restaurant, where she makes good money in tips. What do you say?

Response for High School Teachers: Even more than ability, motivation is crucial for college success, so don’t insist that she attend college immediately. Since your student has money and a steady job (prime goals for today’s college-

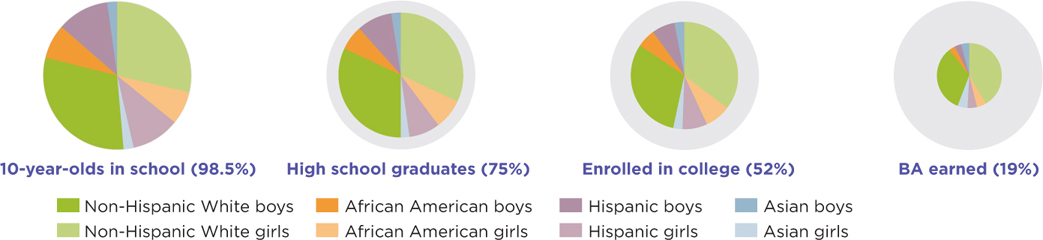

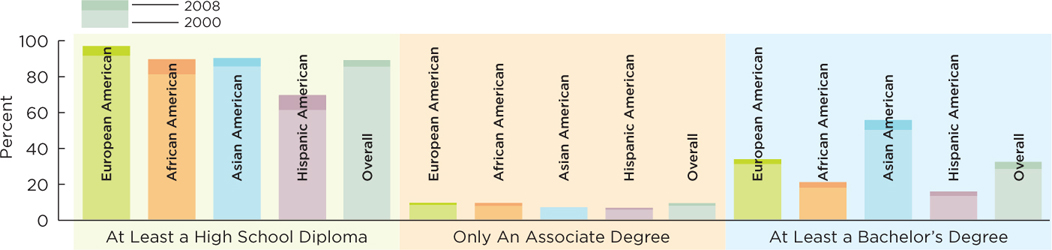

As for a Bachelor’s degree earned by 25-

Not only have the numbers increased, but so have the characteristics of the students. The most obvious change is gender: In 1970, most college students were male; now in every developed nation (except Germany) most students are female. In addition, ethnic, economic, religious, and cultural backgrounds are varied. Compared to 1970, more students are parents, are older than age 24, attend school part time, and live and work off-

Student experiences, histories, skills, and goals are changing as well. Most students are technologically savvy, having spent more hours using computers than watching television or reading. Personal blogs, chat rooms, Facebook pages, and YouTube videos have exploded, often unbeknownst to college staff. Dozens of new networking sites have appeared. Students spend less than one-

The courses that require more reading and writing are unpopular, as are the majors—

The rising importance of material possessions is considered part of the “dark side of emerging adulthood,” as one book describes it (Smith et al., 2012). The same seems true of adults without a college degree: Living well is defined more by financial security and having admirable possessions than by health or caring for the community (Beutler, 2012).

Changes in the Institutions

As massification increases, more colleges are available. Some nations, including China and Saudi Arabia, have recently built huge new universities. In 1955 in the United States, only 275 junior colleges existed; in 2010 there were 1,920 such colleges, now called community colleges. For-

The facilities of the institutions have also changed. Dorms are more luxurious, rooms are larger, athletic facilities more impressive. Prices have increased. For almost half of four-

Other changes are evident. Compared with earlier decades, colleges today offer more career programs and hire more part-

Public colleges have grown, with more than 25,000 undergraduates at each of 100 public universities in the United States. Private colleges still outnumber public ones by a ratio of about 3 to 2, but most U.S. college students (75 percent, or about 14 million) attend publicly-

Income, not ability, continues to be the most significant influence on whether a particular emerging adult will attend college and, once enrolled, will graduate (Bowen et al., 2009). Non-

VISUALIZING DEVELOPMENT

Why Study?

From a life-

EDUCATION IN THE U.S.

AMONG ALL ADULTS

The percentage of U.S. residents with high school and college diplomas is increasing as more of the oldest cohort (often without degrees) dies and the youngest cohorts aim for college. However, many people are insufficiently educated and less likely to find good jobs. It is not surprising that in the recent recession, college enrollment increased. These data can be seen as encouraging or disappointing. The encouraging perspective is that rates are rising for everyone, with the only exception being associate degrees for Asian Americans, and the reason for that is itself encouraging—

INCOME IMPACT

Over an average of 40 years of employment, someone who completes a master’s degree earns $500,000 more than someone who leaves school in eleventh grade. That translates into about $90,000 for each year of education from twelfth grade to a master’s. The earnings gap is even wider than those numbers indicate because this chart includes only adults who have jobs, yet finding work is more difficult for those with less education.

PHOTO: JUPITERIMAGES/THINKSTOCK

Observation Quiz Which is a community college?

Answer to Observation Quiz: The one with the flags is Kingsborough Community College, in Brooklyn; the one with a colonnade is UCLA (University of California in Los Angeles). If you guessed right, what clues did you use?

MELANIE STETSON FREEMAN/THE CHRISTIAN SCIENCE MONITOR VIA GETTY IMAGES

There is also a clear “mismatch between reality and expectations” for students at four-

Evaluating the Changes

This situation again raises the question of what today’s students get out of attending college. The major changes just described might mean that college no longer produces the “greater intellectual flexibility” that earlier research found (Pascarella & Terenzini, 1991). What do the data indicate?

All the evidence on cognition suggests that interactions with people of different backgrounds and various views lead to intellectual challenges and deeper thought, as well as more creative ideas. This occurs most easily if students themselves are bicultural, as an increasing number of United States students are, but simply working with and talking to people of various backgrounds broadens one’s cognitive and cultural perspective (Nguyen & Benet-

Thus, the increased diversity of the student body may encourage cognitive development. Colleges that make use of their diversity—

Of course, many students (and their parents) choose colleges because the student body is similar to the prospective student. Most (81 percent) U.S. freshmen attend a college in their home state. However, every college has some people who are from far away (in the U.S., 3.4 percent come from another nation). Moreover, since each individual has unique genes and experiences, even homogeneous colleges include people with diverse opinions.

A special benefit may come from students who are parents, are employed, attend school part time, and are older than 30. They can enliven conversations and discussions with their fellow students. Some research suggests that those from the least wealthy backgrounds are most likely to benefit, financially and cognitively, from a college degree. However, they are also the most likely to leave before graduation (Bowen et al., 2009).

massive open online course (MOOC) A course that is offered solely online for college credit. Typically, tuition is very low, and thousands of students enroll.

Two new pedagogical techniques may foster greater learning. One is called the flipped class, in which students are required to watch videos of a lecture on their computers before class, and then class time is used for discussion, with the professor prodding and encouraging but not lecturing. The other technique is classes that are totally online, including massive open online courses (MOOCs). A student can enroll in such a class and do all the work off campus.

MOOCs are most likely to be instructive if a student is highly motivated and is adept at computer use, but it also helps if the student has another classmate, or an expert, as a personal guide: Face-

The data suggests that college still advances thinking. A valid comparison can be made with young adults who never attend college. When 18-

Even by age 24, those who attended college and postponed parenthood are more thoughtful and more secure, and seem to be better positioned for a successful adulthood. For this new stage of development—

For many readers of this textbook, none of these findings are surprising. Tertiary education stimulates thought, no matter how old the student is. From first-

SUMMING UP

Many life experiences advance thinking processes. College is one of these experiences, as years of classroom discussion, guided reading, and conversations with fellow students from diverse backgrounds lead students to develop more dynamic and dialectical reasoning. The evidence for this is solid for college education twenty years ago, but today’s students and the institutions that teach them have changed. Students are more interested in jobs than philosophy, and college enrollments have increased in numbers and diversity, with women students now outnumbering men. In many nations other than the United States, an increasing number of young adults are in college, usually with substantial government subsidies. Nonetheless, despite many differences compared to decades ago, the evidence suggests that college education still promotes cognitive development.