Continuity and Change

Continuity and Change

A theme of human development is that continuity and change are evident throughout life. In emerging adulthood, the legacy of childhood is apparent amidst new achievement. Erikson recognized this in his description of the fifth of his eight stages, identity versus role confusion. As you remember, the identity crisis begins in adolescence, but it is not usually resolved until adulthood.

Identity Achieved

Erikson believed that the outcome of earlier crises provides the foundation of each new stage. The identity crisis is an example (see Table 19.1). Worldwide, emerging adults ponder all four arenas of identity—

Past as Prologue In elaborating his eight stages of development, Erikson associated each stage with a particular virtue and a type of psychopathology, as shown here. He also thought that earlier crises could reemerge, taking a specific form at each stage. Listed are some possible problems (not directly from Erikson) that could occur in emerging adulthood if earlier crises were not resolved.

| Stage | Virtue/Pathology | Possible in Emerging Adulthood If Not Successfully Resolved |

|---|---|---|

| Trust vs. mistrust | Hope/withdrawal | Suspicious of others, making close relationships difficult |

| Autonomy vs. shame and doubt | Will/compulsion | Obsessively driven, single- |

| Initiative vs. guilt | Purpose/inhibition | Fearful, regretful (e.g., very homesick in college) |

| Industry vs. inferiority | Competence/inertia | Self- |

| Identity vs. role confusion | Fidelity/repudiation | Uncertain and negative about values, lifestyle, friendships |

| Intimacy vs. isolation | Love/exclusivity | Anxious about close relationships, jealous, lonely |

| Generativity vs. stagnation | Care/rejection | [In the future] Fear of failure |

| Integrity vs. despair | Wisdom/disdain | [In the future] No “mindfulness,” no life plan |

| Source: Erikson, 1982. | ||

As explained in Chapter 16, the identity crisis sometimes causes confusion or foreclosure. A more mature response is to seek a moratorium, postponing identity achievement while exploring possibilities. For instance, earning a college degree is a socially acceptable way to delay marriage and parenthood.

Societies offer many other moratoria: the military, religious mission work, apprenticeships, and various internships in government, academe, and industry. These reduce the pressure to achieve identity, offering a ready rejoinder to an older relative who urges settling down (see Visualizing Development, p. 545).

Emerging adults in moratoria do what is required (as student, soldier, missionary, or whatever), which explains why a moratorium is considered more mature than role confusion. However, they also postpone identity achievement. This respite gives emerging adults some time to achieve in the two arenas that are particularly difficult in current times—

Cultural Identity

As you remember from Chapter 16, aspects of identity change as the historical context changes, even as the search for self determination continues. One expert explains “identity development…from the teenage years to the early 20s, if not through adulthood,…has been extended to explain the development of ethnic and racial identity” (Whitbourne et al., 2009, p. 1328). Ethnic identity includes Erikson’s political and religious identities, both crucial in our modern multiethnic world.

Ethnic identity becomes pivotal when the young person prepares for adulthood. For example, high school senior Natasha Scott “just realized that my race is something I have to think about” (Saulny & Steinberg, 2011, p. A-

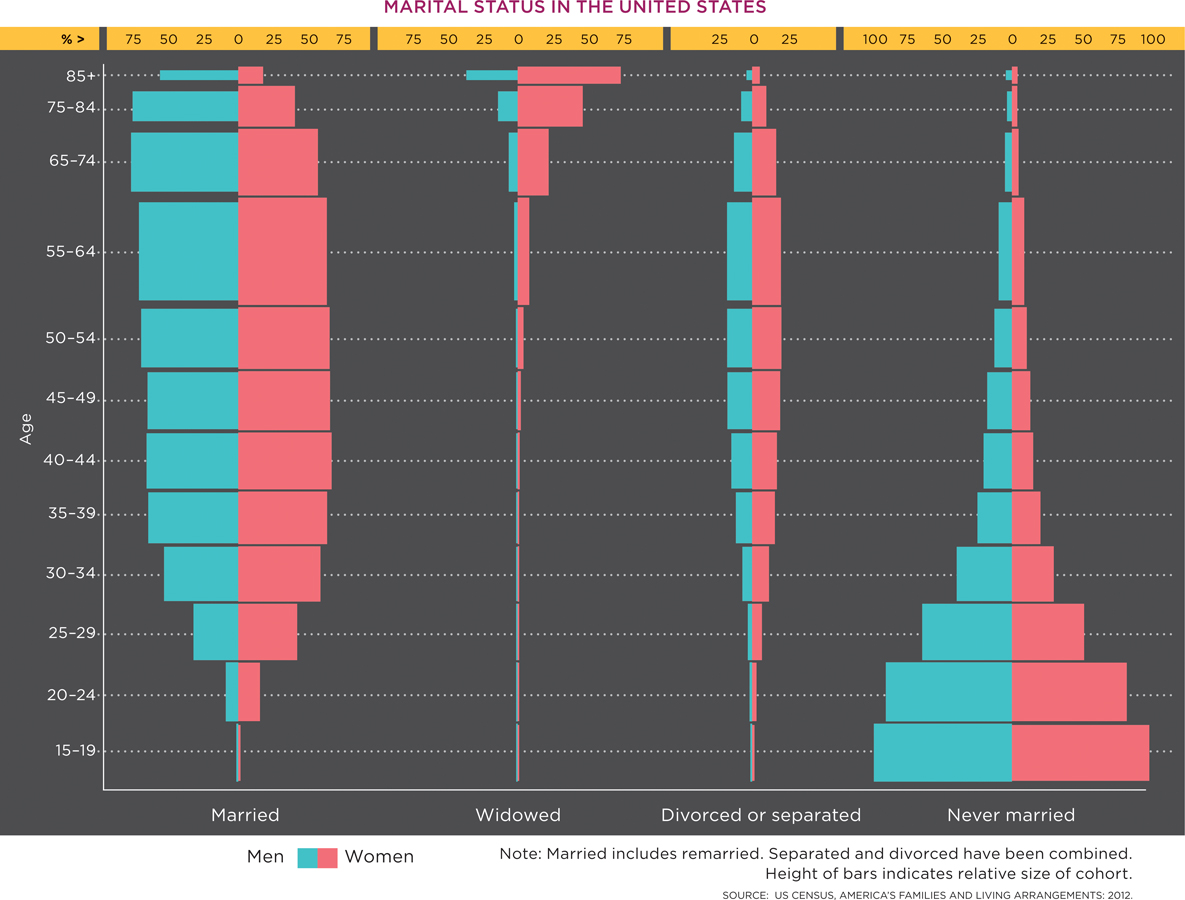

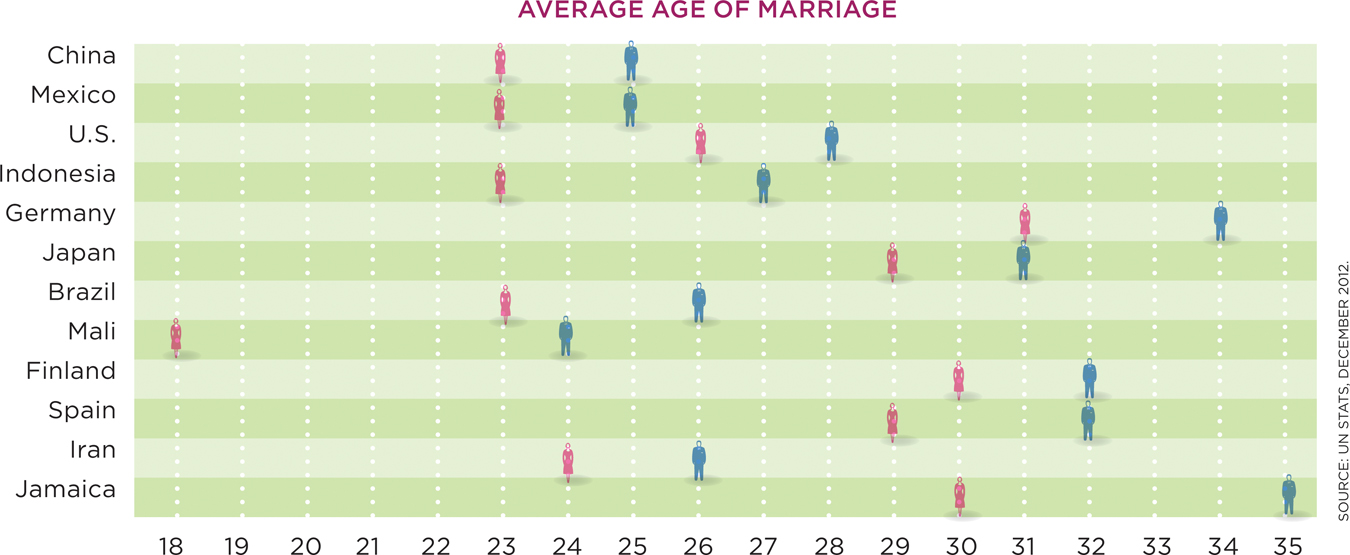

VISUALIZING DEVELOPMENT

Marital Status in the United States

Adults seek committed partners, but do not always find them—

SOURCES & CREDITS LISTED ON P. SC-

Natasha is not alone. In the United States and Canada, almost half of 18-

For an increasing number of emerging adults, those diverse ancestors are their parents. Intermarriage (between adults from diverse racial groups) in the United States was less than 7 percent in 1980, more than 15 percent in 2010 (Wang, 2012). Their children are typically proudly bicultural. Beyond that are millions of other emerging adults whose heritage includes more than one nation. Bicultural identity correlates with healthy psychosocial development, not the opposite (Nguyen & Benet-

No matter what their background is, college students who explore their ethnic identity experience less anger and anxiety, although, as is true of every other aspect of identity, some people become stuck trying to figure out what it means to be themselves (Richie et al., 2013). One study found that Hispanic college students who resisted both assimilation and alienation fared best: They were most likely to maintain their ethnic identity, deflect stereotype threat, and become good students (Rivas-

Young adults whose parents were immigrants have an immediate challenge—

One example is whether or not young adults listen to their parents’ advice. In mainstream American culture, unsolicited parental advice is not welcome. Yet among many cultures (including some American subcultures) family members offer opinions about everything from clothing styles to marriage partners—

Some emerging adults become more dedicated to their ethnic/religious identity than their parents are. For example, young Arabic women in Western nations may choose to wear the hijab, the headscarf that indicates they are observant Muslims, even when their parents wish they would not. Paradoxically, the headscarf may make it easier for them to attend college and secure employment with non-

Generally, having a firm identity frees a person to interact with people of other identities. More than other age groups, emerging adults tend to have friends and acquaintances of many backgrounds. As they do so, they become more aware of history, customs, and prejudices. Many refuse to limit themselves to one ethnicity, one culture, one nation: Some defiantly write “human” when a questionnaire asks, “Race?”

As emerging adults undergo cognitive development, many of them strive to combine objective and subjective identity: They take courses in history, ethnic studies, and sociology, and they also seek close friends, lovers, and affinity groups whose identity struggles are similar to their own. Emerging adults strive to combine academic and personal connections in their ethnic identity, similar to their struggle to achieve sexual identity, as described in Chapter 16.

Vocational Identity

Establishing a vocational identity is considered part of growing up, not only by developmental psychologists influenced by Erikson but also by emerging adults themselves. Many go to college to prepare for a good job. Emerging adulthood is a “critical stage for the acquisition of resources”—including the education, skills, and experience needed for lifelong family and career success (Tanner et al., 2009, p. 34) (see Table 19.2).

Look Again This research was already mentioned in Chapter 18, but now compare the cited objectives to the reality of the job market. Contemporary emerging adults are finding it difficult to achieve vocational identity. If projections prove accurate, many of them will not consider themselves “well-

| Being well off financially | 78% |

| Raising a family | 75% |

| Making more money | 71% |

| Helping others | 69% |

| Becoming an authority in my field | 59% |

| Obtaining recognition in my special field | 56% |

|

*Based on a national survey of students entering four- |

|

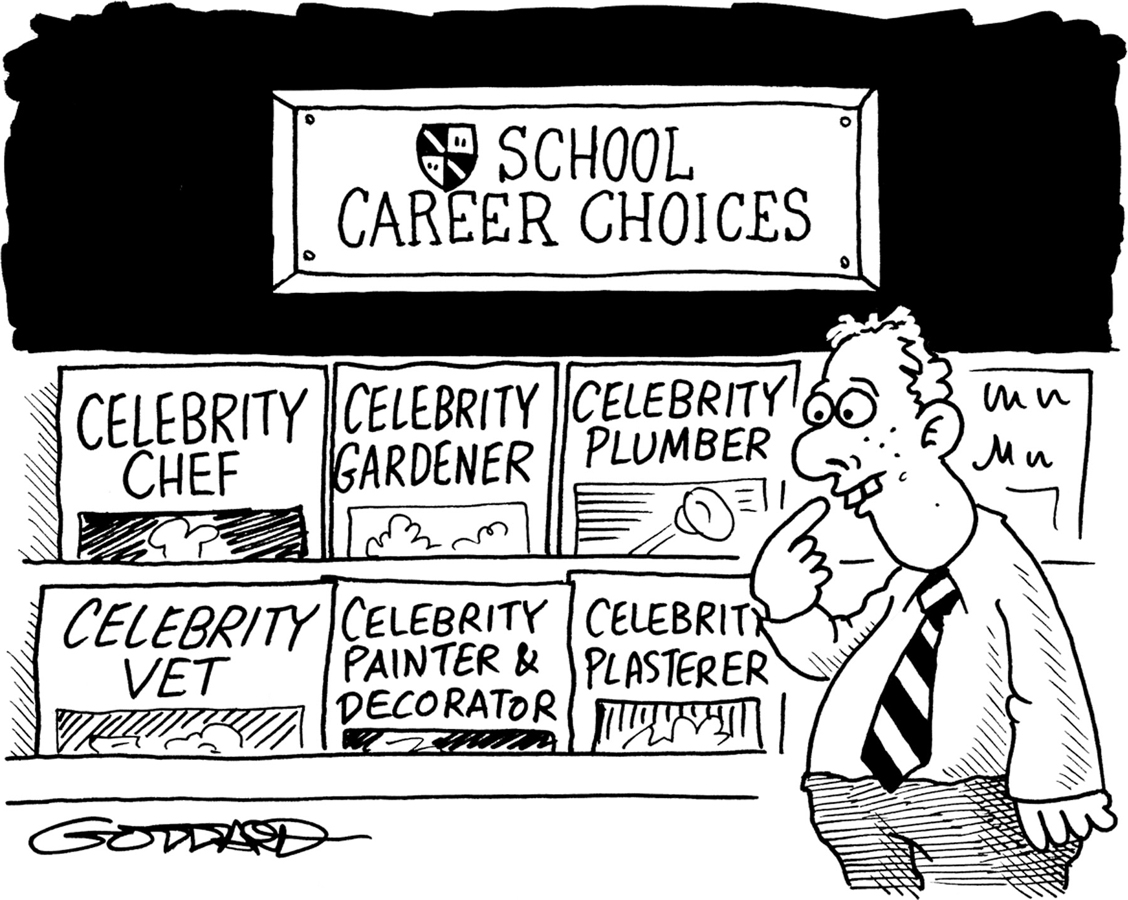

Unfortunately, achieving vocational identity is more difficult than ever. Children tend to want work that fewer than one in a million of them will ever obtain—

For such practical concerns, adults are of little help. Parents usually know only their particular work, not what labor-

Counselors often have neither the time nor the expertise to offer vocational guidance (Zehr, 2011). College counselors may be more skillful than their high school counterparts, but many are overwhelmed by the need to counsel students with serious emotional problems, as detailed in Chapter 17.

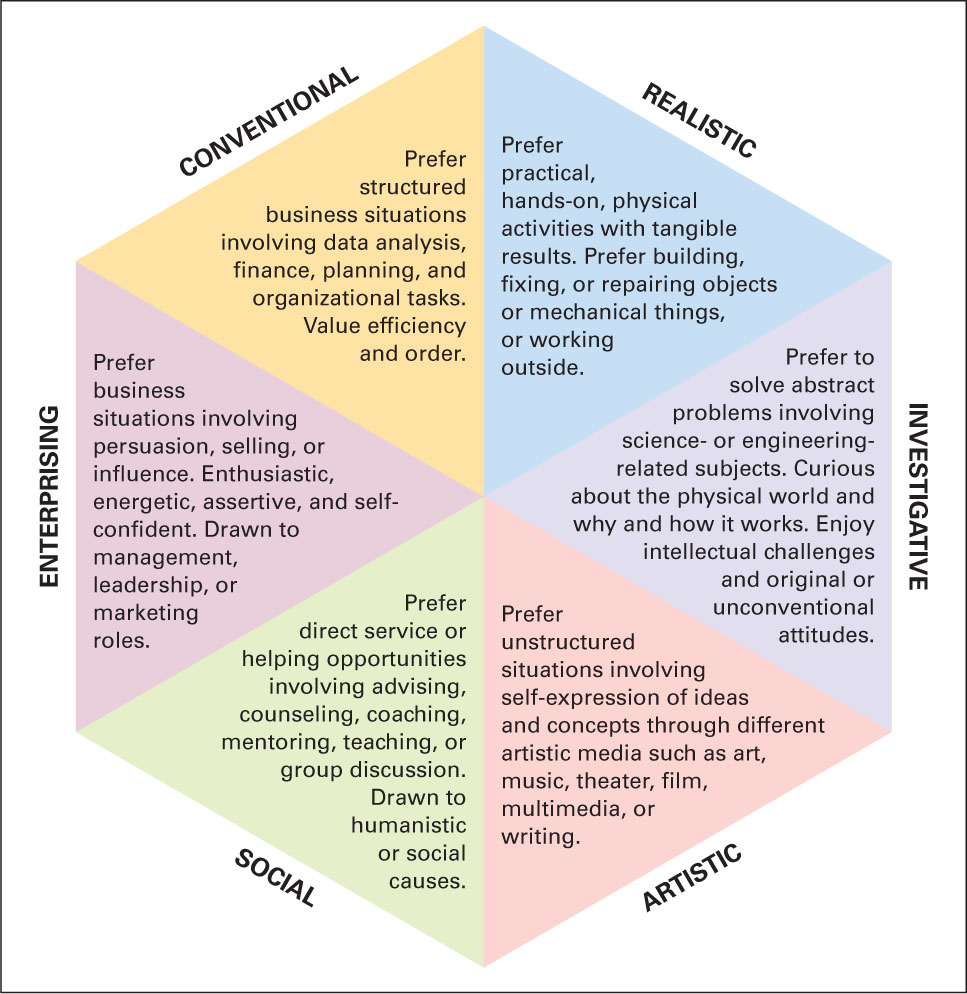

Thus many emerging adults contemplating future careers are left on their own. John Holland’s description (1997) of six possible interests (see Figure 19.1, p. 548) offers some help to these students. Unfortunately, however, even if they know what they want and they earn their degree, many are unable to find the work they want. This has been particularly true since the economic downturn that began in 2008: Emerging adults are the age group with the highest rate of unemployment (Draut & Rueschin, 2013).

FIGURE 19.1

Happy at Work John Holland’s six-Today’s job market has made development of vocational identity particularly difficult for emerging adults. A life-

Many young people take a series of temporary jobs. Between ages 18 and 25, the average U.S. worker has held six jobs, with the college-

© SHANNON STAPLETON/REUTERS/CORBIS

Personality in Emerging Adulthood

Continuity and change are evident in personality as well (McAdams & Olson, 2010). Of course, personality is shaped lifelong by genes and early experiences:

If self-

Yet personality is not static. After adolescence, new personality dimensions may appear. As the preceding two chapters emphasize, emerging adults make choices that break with the past. Unlike youth in previous generations, contemporary youth are more likely to pursue higher education and postpone marriage and parenthood. Their freedom from a settled lifestyle allows shifts in attitude and personality.

Many researchers study what factors lead a young adult to thrive in secondary and tertiary education. Background and genes are influential, but so is personality. Not only is success in school affected by personality but it also affects personality (Klimstra et al., 2012). In other words, college success can change personality traits for the better.

Rising Self-Esteem

One team of researchers traced the experiences of 3,912 U.S. high school seniors until age 23 or 24. Generally, chosen transitions (entering college, starting a job, getting married) increased well-

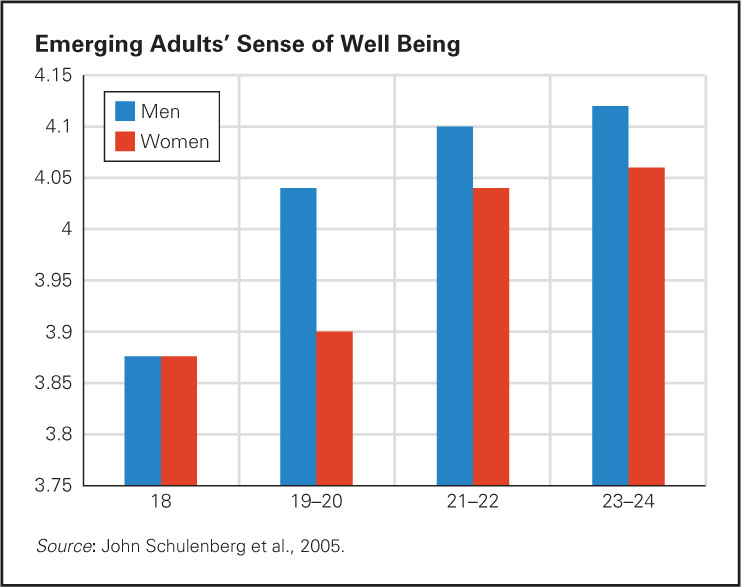

FIGURE 19.2

Worthy People This graph shows a steady, although small, rise in young adults’ sense of well-Some increasing happiness may be part of becoming more adult: Young adults in western Canada, repeatedly questioned from ages 18 to 25, reported increasing self-

Logically, the many stresses and transitions of emerging adulthood might be expected to reduce self-

Worrisome Children Grow Up

Shifts toward positive development were also found in another longitudinal study that began with 4-

This is not to say that old patterns disappeared. For example, those who had been aggressive 4-

Yet, unexpectedly, these aggressive young adults had as many friends as their average peers did. They wanted more education than they already had, and their self-

As for the emerging adults who had been shy, they were “cautious, reserved adults” (Asendorpf et al., 2008, p. 1007), slower than average to secure a job, choose a career, or find a romance (at age 23, two-

A major reason for the increasing self-

Plasticity

In the research just discussed and in other research as well, plasticity (which, as you remember, refers to the idea that development is both moldable and durable, like plastic) is evident. Personality is not fixed by age 5, or 15, or 20, as it was once thought to be. Emerging adults are open to new experiences (a reflection of their adventuresome spirit), an attitude that allows personality shifts as well as eagerness for more education (McAdams & Olson, 2010; Tanner et al., 2009).

plasticity genes Genes and alleles that make people more susceptible to environmental influences, for better or worse. This is part of differential sensitivity.

Clearly, genes do not determine behavior, but they do make a person more or less susceptible to environmental forces. Some genes have been called plasticity genes (Simons et al., 2013). A person who inherits them is affected, for better or for worse, by going to college, leaving home, becoming independent, stopping drug abuse, moving to a new city, finding satisfying work and performing it well, making new friends, committing to a partner.

Although total change does not occur, since genes, childhood experiences, and family circumstances affect people lifelong, personality can shift in adulthood. Increased well-

SUMMING UP

The identity crisis continues in emerging adulthood as young people seek to establish and follow their own unique path. Achieving ethnic identity is important but difficult, especially for those who realize they are a minority within their nation. Vocational identity is also an ongoing search. Most emerging adults hold many jobs between the ages of 18 and 25, but few feel they have established a career identity. Personality traits endure lifelong, partly because genes and early childhood are influential, but emerging adults modify some traits and develop others.