19.2 Intimacy

intimacy versus isolation The sixth of Erikson’s eight stages of development. Adults seek someone with whom to share their lives in an enduring and self-

In Erikson’s theory, after achieving identity, people experience the crisis of intimacy versus isolation. This crisis arises from the powerful desire to share one’s personal life with someone else. Without intimacy, adults suffer from loneliness. Erikson explains:

The young adult, emerging from the search for and the insistence on identity, is eager and willing to fuse his identity with others. He is ready for intimacy, that is, the capacity to commit himself to concrete affiliations and partnerships and to develop the ethical strength to abide by such commitments, even though they call for significant sacrifices and compromises.

[Erikson, 1963, p. 263]

As will be explained in Chapter 22, other theorists have different words for the same human need: affiliation, affection, interdependence, communion, belonging, love. All agree that adults seek to become friends, lovers, companions, and partners, with the “significant sacrifices and compromises” that entails. The urge for social connection is a powerful human impulse, one reason our species has thrived.

All intimate relationships have much in common—

face the fear of ego loss in situations which call for self-

[Erikson, 1963, pp. 163–

Friendship

According to a more recent theory, an important aspect of close human connections is self-

Whether or not friends expand our minds, it is certain that friends strengthen our mental and physical health (Seyfarth & Cheney, 2012). Unlike relatives, friends are chosen (not inherited). Friends seek understanding, tolerance, loyalty, affection, humor from one another—

Friends in Emerging Adulthood

Friendships “reach their peak of functional significance during emerging adulthood” (Tanner & Arnett, 2011, p. 27). Since fewer emerging adults have the family obligations that come with spouses, children, or frail parents, their friends provide needed companionship and critical support.

Friends comfort each other when romance turns sour, and they share experiences and information about everything from what college to attend to what socks to wear. One crucial question for emerging adults is what and how to tell parents news that might upset them: Friends help with that, too.

People tend to make more friends during emerging adulthood than at any later period, and they rely on them. They often use social media to extend and deepen friendships that begin face to face, becoming more aware of the day-

552

JODI COBB/NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC/GETTY IMAGES

Gender and Friendship

It is a mistake to imagine that men and women have opposite friendship needs. All humans seek intimacy, throughout their lives. Claiming that men are from Mars and women are from Venus ignores reality: People are from Earth (Hyde, 2007).

Nonetheless, for cultural and biological reasons, some sex differences can be found. Men tend to share activities and interests, and they talk about external matters—

A meta-

By contrast, men are less likely to touch each other except in aggressive activities, such as competitive athletics or military combat. The butt-

Lest this discussion seem to imply that female friendships are better because they are closer, research finds that men are more tolerant; they demand less from their friendships than women do, and thus they have more friends (Benenson et al., 2011). One specific detail from college dormitories is revealing: When strangers of the same sex are assigned as roommates (as occurs for first-

Male-Female Friendships

As already noted, these gender differences may be cultural, not biological, and are changing. One sign of such changes is the frequency of male–

Cross-

553

Especially for Young Men Why would you want at least one close friend who is a woman?

Response for Young Men: Not for sex! Women friends are particularly responsive to deep conversations about family relationships, personal weaknesses, and emotional confusion. But women friends might be offended by sexual advances, bragging, or advice giving. Save these for a future romance.

Problems arise if outsiders assume that every male–

Humans apparently find it difficult to sustain more than one sexual/romantic relationship at a time. Indeed, even in nations where polygamy is accepted, 90 percent of husbands have only one wife (Georgas et al., 2006). A study of couples in Kenya, where polygamy is legal, found that actual or suspected sexual infidelity was the most common reason for breaking up (Clark et al., 2010), and a study in the United States found that emerging adults thought sexual fidelity was crucial for a good, enduring relationship (Meier et al., 2009).

The Dimensions of Love

“Love” itself has many manifestations. In a classic analysis, Robert Sternberg (1988) described three distinct aspects of love: passion, intimacy, and commitment. The presence or absence of these three gives rise to seven different forms of love (see Table 19.3).

| Present in the Relationship? | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Form of Love | Passion | Intimacy | Commitment |

| Liking | No | Yes | No |

| Infatuation | Yes | No | No |

| Empty love | No | No | Yes |

| Romantic love | Yes | Yes | No |

| Fatuous love | Yes | No | Yes |

| Companionate love | No | Yes | Yes |

| Consummate love | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Source: Sternberg, 1988. | |||

Early in a relationship, passion is evident in “falling in love,” an intense physical, cognitive, and emotional onslaught characterized by excitement, ecstasy, and euphoria. The entire body and mind, hormones and neurons, are activated (Aron, 2010). Such moonstruck joy can become bittersweet as intimacy and commitment increase. As one observer explains, “Falling in love is absolutely no way of getting to know someone” (Sullivan, 1999, p. 225).

Intimacy is knowing someone well, sharing secrets as well as sex. This aspect of a romance is reciprocal, with each partner gradually revealing more of himself or herself as well as accepting more of the other’s revelations.

The research is not clear about the best schedule for passion and intimacy, whether they should progress slowly or quickly, for instance. According to some research, they are not always connected, as lust arises from a different part of the brain than affection (Langeslag et al., 2013).

Commitment takes time and effort, at least for those who follow the current Western pattern of love and marriage. It grows through decisions to be together, mutual caregiving, shared possessions, and forgiveness (Schoebi et al., 2012). Social forces strengthen or undermine commitment; that’s why in-

Commitment is also affected by the culture. In fact, when cultures endorse arranged marriages, commitment occurs early on, before passion or intimacy (Georgas et al., 2006). Having friends and acquaintances who do, or do not, endorse the value of committed relationship affects each couple.

For example, in Sweden couples who lived in detached houses (with yards between them) broke up more often than did couples living in attached dwellings (such as apartments). Perhaps “single-

554

When children are born, passion seems to fade for both partners, but commitment increases. This may be one reason why most sexually active young adults try to avoid pregnancy unless they believe their partner is a lifelong mate. [Lifespan Link: The relationship of parenthood to marital satisfaction is discussed in Chapter 22.]

The Ideal and the Real

In Europe in the Middle Ages, love, passion, and marriage were considered to be distinct phenomena, with “courtly love” disconnected from romance, which was also distinct from lifelong commitment (Singer, 2009). Currently, however, the Western ideal of consummate love includes all three components: passion, intimacy, and commitment.

For developmental reasons, this ideal is difficult to achieve. Passion seems to be sparked by unfamiliarity, uncertainty, and risk, all of which are diminished by the familiarity and security that contribute to intimacy and by the time needed for commitment.

In short, with time, passion may fade, intimacy may grow and stabilize, and commitment may develop. This pattern occurs for all types of couples—

Emerging adults refer to “friends with benefits,” implying that sexual passion is less significant (an extra benefit, not the core attraction) than the friendship. As with other friendships, shared confidences and loyalty are the important parts of the relationship, with sexual interactions almost an afterthought. To use Sternberg’s triadic theory, the relationship is intimate but not passionate.

However, if a friendship becomes sexual, complications arise (Owen & Fincham, 2011). Once the hormones of sexual intimacy are activated, people may become more emotionally involved than they expected. Such involvement may be more welcomed than feared. Young adults who add sex to a friendship may hope for romance (Mongeau et al., 2011).

Hookups Without Commitment

hookup A sexual encounter between two people who are not in a romantic relationship. Neither intimacy nor commitment is expected.

A sexual relationship that is not intended to become a romance, with no true intimacy or commitment, is a hookup. When this relationship occurred in prior generations, it was either prostitution or illicit, as in a “fling” or a “dirty secret.” No longer. It is estimated that about half of all emerging adults have hooked up. Hookups often involve intercourse but not necessarily: The crucial factor is that sexual interaction of some sort occurs between partners who do not know each other well, perhaps having met just a few hours before.

Hookups are more common among first-

The desire for physical intimacy without emotional commitment is stronger in young men than in young women, either for hormonal (testosterone) or cultural (women want committed fathers if children are born) reasons. One sociologist writes:

While women are preparing for adult life, guys are in a holding pattern. They’re hooking up rather than forming the kind of intimate romantic relationships that will ready them for a serious commitment; taking their time choosing careers that will enable them to support a family; and postponing marriage, it seems, for as long as they possibly can.

[Kimmel, 2008, p. 259]

555

As contraception, employment, and college education have changed women’s lives, this “guy” pattern includes more females. Nonetheless, by age 25, more women than men have married (44 percent compared to 31 percent) (Copen et al., 2012). Interestingly, emerging adults of both sexes who want a serious relationship with someone state that they are less likely to hook up with them, preferring to get to know them first.

Finding Each Other and Living Together

One major innovation of the current cohort of emerging adults is the use of social networks, as the online connections between dozens or hundreds of people are called. Almost all (83 percent) U.S. 18-

Many young adults seeking romance join one or more matchmaking Web sites that provide dozens of potential partners to meet and evaluate. A problem with such matches is that passion is hard to assess without meeting in person. As one journalist puts it, many people face “profound disappointment when the process ends in a face-

Emerging adults overcome this problem by filtering their online connections, meeting only those who seem promising, and then arranging a second meeting with only a few. Often physical attraction is the gateway to a relationship, but intimacy and then commitment require much more. When online connections lead to face-

choice overload Having so many possibilities that a thoughtful choice becomes difficult. This is particularly apparent when social networking and other technology make many potential romantic partners available.

The large number of possible partners young adults find—

EVY MAGES/THE WASHINGTON POST/GETTY IMAGES

556

Choice overload occurs with many consumer goods—

cohabitation An arrangement in which a couple live together in a committed romantic relationship but are not formally married.

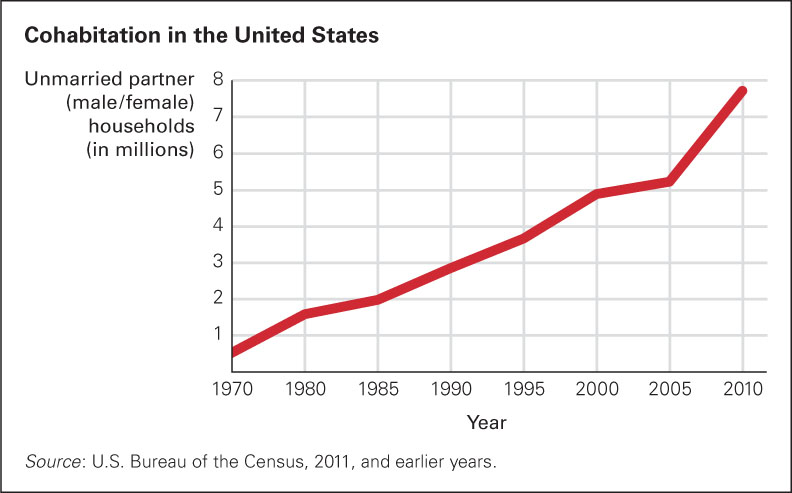

A second major innovation among emerging adults is cohabitation, the term for living together in a romantic partnership without being married. Cohabitation was relatively unusual 40 years ago: In the United States, less than 1 percent of all households were comprised of a cohabiting man and woman (see Figure 19.3). Between 2008 and 2012, 60 percent of all adults cohabited before they married, and another 11 percent continued to cohabit, perhaps never to marry (Copen et al., 2013).

Cohabitation rates vary from nation to nation: It is the norm in the United States, Canada, northern Europe, England, and Australia but not in other nations—

557

Variation is also apparent in the purpose of cohabitation (Jose et al., 2010). About half of all cohabiting couples in the United States consider living together a prelude to marrying, which they expect to do when they are financially and emotionally ready. Many reach that point within three years. To be specific, a U.S. survey from 2006 to 2010 found that 40 percent of women in a first premarital cohabitation transitioned to marriage within three years, 32 percent were still cohabiting, and 27 percent had separated.

Overall, the quality of adult romantic relationships reflects early attachment styles, both anxious (too clingy and jealous) and avoidant (too distancing and secretive) (Collins & Gillath, 2012; Li & Chan, 2012). Adults who were securely attached infants are more likely to have secure relationships with their spouses as well as with their own children. Of course, plasticity is evident lifelong; early attachment affects adult relationships, but it does not determine them.

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

Cohabitation

Many emerging adults consider cohabitation to be a wise prelude to marriage, a way for people to make sure they are compatible before tying the knot and thus reducing the chance of divorce. However, research suggests the opposite.

Contrary to widespread belief, living together before marriage does not prevent problems that might arise after a wedding. In a meta-

Another study looked at the effects of dating, cohabitation, and marriage on happiness, as assessed by participants’ answers to four questions (rated on a scale of 1 to 7) about how “ideal,” “excellent,” “satisfying,” and “accomplished” their life was (Soons et al., 2009). At the start of any romantic relationship—

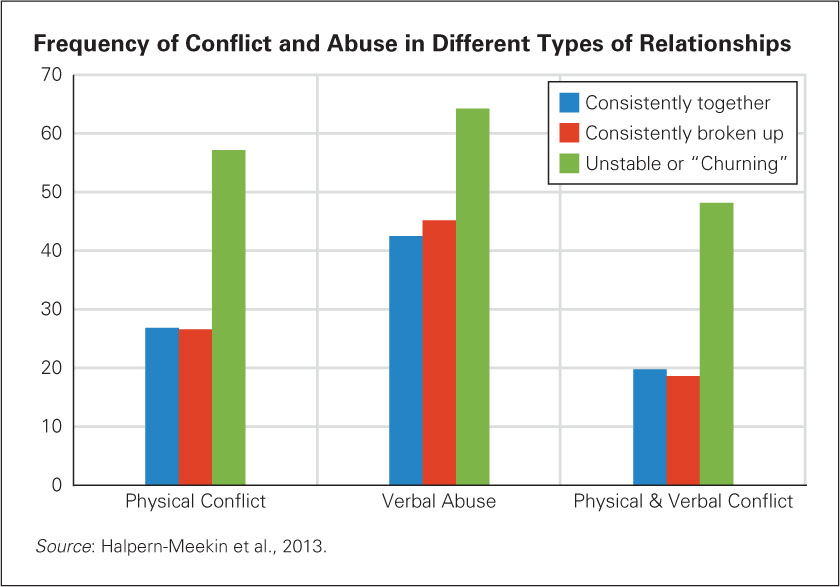

Particularly problematic is churning, when couples live together, then break up, then come back together. Churning relationships have high rates of verbal and physical abuse (Halpern-

Although the research suggests many problems with cohabitation, most emerging adults engage in this lifestyle. Of course, humans tend to justify whatever they do. In this case, cohabiting adults typically think they have found intimacy without the restrictions of marriage, but they may be fooling themselves.

However, most published research on the long-

More-

558

Of course, cohabitation has one decided advantage: People save money by living together. Since the economic downtown has affected emerging adults more than older adults, this may be one reason for the current popularity of cohabitation.

National culture matters as well. Research in 30 nations finds that acceptance of cohabitation within the nation affects the happiness of those who cohabit. Within each of those 30 nations, demographic differences (such as education, income, age, and religion among the married and cohabitants) affect the happiness gap between cohabitation and marriage (Soons & Kalmijn, 2009). Another international study found that in Austria, Belgium, Denmark, New Zealand, Poland, Germany, and Norway, cohabitants were happier than married people (Lee & Ono, 2012).

All this suggests caution—

Those 16 million chose a living arrangement other than the one that most research considers best. Do they know something that past research has not yet discovered?

Changing Historical Patterns

Love, romance, and lasting commitment are all of primary importance for emerging adults, although many specifics have changed. As already mentioned, a defining characteristic of emerging adults is that they marry later: In the United States the average age at first marriage was 29 for men and 27 for women in 2012. This was three years later than in 2000 and six years later than in 1950.

Marriage is not what it once was—

Further evidence is found in U.S. statistics (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2013):

Especially for Social Scientists Suppose your 25-

Response for Social Scientists: First, Canada’s divorce rate is not as high as the United States. Second, the divorce rate in the United States comes from dividing the number of divorces by the number of marriages. Because some people are married and divorced many times, that minority provides data that drive up the ratio and skew the average. (Actually, even in the United States, only one first marriage in three—

- Only half of all adults are married, living with their spouse.

- Only 12 percent of all emerging adults, ages 18–

25, are married. - The divorce rate is about half the marriage rate, not because more people are divorcing but because fewer people are marrying.

- Women having their first baby under age 30, are more often unmarried than married.

Such statistics make some fear that marriage is a dying institution. However, few developmentalists agree with that assessment, partly because emerging adults may be postponing, not abandoning, marriage. In fact, it seems that they have higher expectations for marriage than previous cohorts did, and they still see marriage as a marker of maturity and success (Cherlin, 2009). The efforts gay and lesbian couples have made to achieve marriage equality, and the backlash in “defense of marriage,” suggest the power of the institution (Obocock, 2013).

What does seem to have occurred, however, is a change in the relationship between love and marriage. Three distinct patterns were evident in the twentieth century.

In about one-

The “one-

Currently, the practice in developing nations often blends these two types. For example, in modern India most brides believe they have a choice, but many meet their future husbands a few days before the wedding via parental arrangement. Typically, the man has more say in the union than the woman. The woman can refuse the match, but that is unusual (Desai & Andrist, 2010).

The final pattern is relatively new, although familiar to most readers of this book, and is becoming the most common one. Young people socialize with hundreds of others and are expected to fall in love but not marry until they are able to be independent, both financially and emotionally. Their choices tilt toward personal qualities observable at the moment—

For instance, a person who has been married and divorced is seen much more negatively by parents than by unpartnered adults (Buunk et al., 2008). In parts of India, love marriages have become more popular than arranged marriages, but marrying someone of a higher or lower caste is still much more troubling to the parents than to the emerging adults (Allendorf, 2013).

For Western emerging adults, love is considered a prerequisite for marriage, according to a survey of 14,121 individuals of many ethnic groups and sexual orientations (Meier et al., 2009). They were asked to rate from 1 to 10 the importance of money, same racial background, long-

This survey was conducted in North America, but emerging adults worldwide share similar values. Halfway around the world, emerging adults in Kenya also reported that love was the main reason for couples to form and endure; money was less important (Clark et al., 2010). Elsewhere in Africa, although parental approval is more important than in the U.S., love between the couple is nonetheless crucial (Cole & Thomas, 2009).

560

A CASE TO STUDY

My Daughters and Me

I take some comfort in the idea that later marriages occur between people who want more from each other. I married late for my cohort (at age 25) and had children even later (two by age 30 and another two by age 40). Of my four children, only one is married—

For those reasons, I pay close attention to my students’ thoughts about love and marriage. Emerging adult Kerri wrote:

All young girls have their perfect guy in mind, their Prince Charming. For me he will be tall, dark, and handsome. He will be well educated and have a career with a strong future…a great personality, and the same sense of humor as I do. I’m not sure I can do much to ensure that I meet my soul mate. I believe that is what is implied by the term soul mate; you will meet them no matter what you do. Part of me is hoping this is true, but another part tells me the idea of soul mates is just a fable.

[Personal communication]

Kerri’s classmate Chelsea, also an emerging adult, wrote:

I dreamt of being married. The husband didn’t matter specifically, as long as he was rich and famous and I had a long, off-

[Personal communication]

Neither of these students is naive. Kerri uses the words Prince Charming and fable to express her awareness that these ideas may be childish, and Chelsea seems to have moved beyond her “long, off-

But as a mother, I wish they would all have loving partners. I even imagine them owning houses with lawns, picket fences, children, and pets. My wishes are not logical. Postformal thinking makes me aware that I am stuck in traditional norms and that such homes are bad for the planet. My daughters’ ideas and practices are more suited to the twenty-

What Makes Relationships Succeed?

As already stated, friendships and romances have much in common. They satisfy the need for intimacy. Friends and mates are selected in similar ways, with mutual commitments gradually increasing until someone becomes a lifelong best friend or a chosen partner. Best friends sometimes part, and long-

Another similarity is that close friendships and happy marriages aid self-

Changes over Time

From a developmental perspective, note that marriages evolve over time, sometimes getting better and sometimes worse. Among the factors that lead to i mprovement are good communication, financial security (more income or new employment), and the end of addiction or illness. Children are an added stress, with adolescents particularly trying for both parents (Cui & Donnellan, 2009).

Another developmental factor is maturity. In general, the younger the partners, the more likely they are to fight and separate, perhaps because, as Erikson recognized, intimacy is elusive before identity is achieved. An emerging adult who finally achieves identity might think, “I finally know who I am, and the person I am does not belong with the person you are.”

561

Similarities and Differences

homogamy Defined by developmentalists as marriage between individuals who tend to be similar with respect to such variables as attitudes, interests, goals, socioeconomic status, religion, ethnic background, and local origin.

heterogamy Defined by developmentalists as marriage between individuals who tend to be dissimilar with respect to such variables as attitudes, interests, goals, socioeconomic status, religion, ethnic background, and local origin.

Similarity tends to solidify commitment, probably because similar people are likely to understand each other. Anthropologists distinguish between homogamy, or marriage within the same tribe or ethnic group, and heterogamy, marriage outside the group.

Traditionally, homogamy meant marriage between people of the same cohort, religion, SES, and ethnicity. For contemporary partners, homogamy and heterogamy also refer to similarity in interests, attitudes, and goals. Educational and economic similarity are becoming increasingly important, and ethnic similarity less so (Clark et al., 2010; Hamplova, 2009; Schoen & Cheng, 2006).

The data are clear on this issue. One in seven current marriages in the United States is officially counted as interethnic (Wang, 2012). Very broad ethnic categories are used. For example, Black people from Africa, the Caribbean, and America were considered one ethnic group; Asians from more than a dozen nations were another ethnicity; European ancestry was a third category, lumping eastern, western, northern, and southern Europe together.

Thus, a marriage between a Pakistani and a Chinese person would not be categorized as interethnic. Nor would a marriage between a person of Greek heritage and one of Norwegian ancestry, even though the couple might be well aware of ethnic differences. Given the reality of cultural differences, perhaps most marriages in the U.S. are not homogamous.

One thorny issue that arises among couples who live together involves the allocation of domestic work, which varies dramatically by culture. In some cultures and in the United States in earlier decades, if the husband had a good job and the wife kept the household running smoothly, each partner was content. This is no longer the case.

Many twenty-

Today, partners expect each other to be friends, lovers, and confidants as well as wage earners and caregivers, with both partners cooking, cleaning, and caring for children—

As women earn more money and men do more housework, increased shared responsibilities may increase marital satisfaction. Although many aspects of marriage have changed over the decades (some increasing happiness, some not), in general, couples seem as happy with their relationship as they ever were (Amato et al., 2003). Indeed, the U.S. divorce rate for first marriages seems to have decreased since 2000.

Conflict

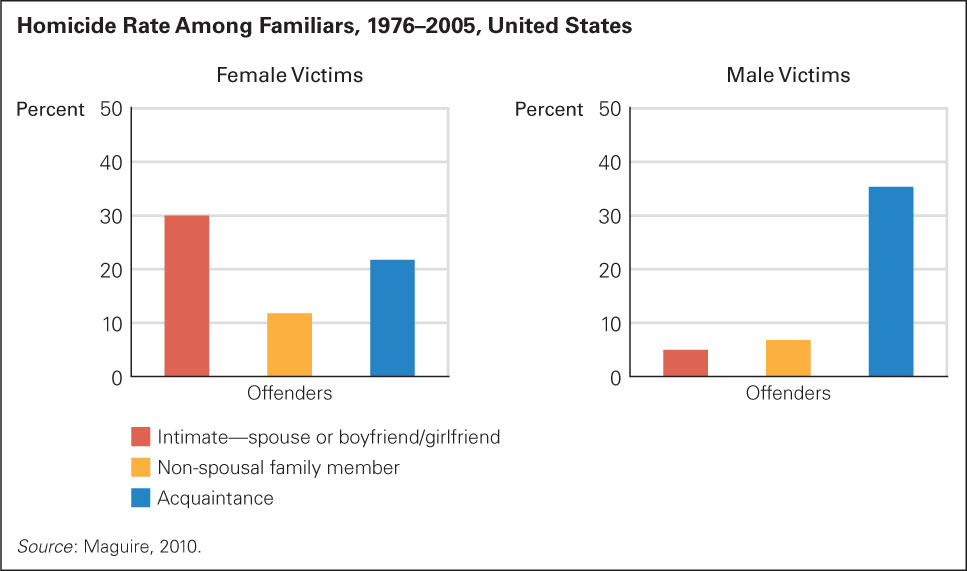

Every intimate relationship has the potential to be destructive. The most extreme example comes from homicide statistics: When a civilian person is killed, the perpetrator is usually a friend, an acquaintance, or a relative—

Amicable distancing is less acceptable and more painful for married couples. We focus here on factors that make typical couples less happy than they might be and then on intimate partner violence. Some conclusions apply to friendships as well.

562

Learning to Listen

No relationship is always smooth; each individual has unique preferences and habits. I know this personally. My husband was much more bothered by disorganization than I was, something we had not realized when we were dating. But early in our marriage, he bought a plastic container that fit in a drawer in the top of our kitchen cabinet, and organized all the silverware, separating salad and dinner forks, soup and table spoons, and so on. I was furious; I liked my way, resented his actions, and blurted out half a dozen reasons why he was wrong and I was right. Fortunately, we figured out what was beneath my anger, and that fight became a joke in later decades.

If a couple “fights fair,” using humor and attending to each other’s emotions as they disagree, conflict can contribute to commitment and intimacy (Gottman et al., 2002). According to John Gottman, who has videotaped and studied thousands of couples, conflict is less predictive of separation than disgust because disgust closes down intimacy.

Not every researcher agrees. Some studies of young couples (dating, cohabiting, and married) report that conflict undermines the relationship. However, every social scientist agrees that communication skills are crucial (Wadsworth & Markman, 2012). Much depends on how the conflict ends—

demand/withdraw interaction A situation in a romantic relationship wherein one partner wants to address an issue and the other refuses, resulting in opposite reactions—

One particularly destructive pattern is called demand/withdraw interaction—

An international study of young adults in romantic relationships (again, some dating, some cohabiting, some married) in Brazil, Italy, Taiwan, and the United States found that women were more likely demand and men withdraw, although even when sex roles were reversed, the pattern was harmful. The authors explain:

If couples cannot resolve their differences, then demand/withdraw interaction is likely not only to persist but also to become extreme. We believe that demand and withdraw may potentiate each other so that demanding leads to greater withdrawal and withdrawal leads to greater demanding. This repeated but frustrating and painful interaction can then damage relationship satisfaction.

[Christensen et al., 2006, p. 1040]

563

Intimate Partner Violence

An unmet demand may cause domestic abuse, which obviously is far worse than mere “damage to relationship satisfaction.” In some abusive relationships, constructive communication is impossible; in others, mediation can teach both partners how to improve their relationship.

Young couples especially need such help because emerging adults are more likely to be victims and perpetrators of domestic abuse than people of any other age. For example, a large longitudinal study (Add Health) that began with a cross section of thousands of adolescents in the United States, most of them not in serious romantic relationships. In their early 20s, many were dating, cohabiting, or married, They were asked if there was verbal (“You’re ugly”; “You’re stupid”) or physical (slapping, beating, kicking) abuse. Close to half (41 percent) said yes. Because this study is large and prospective, that 41 percent is probably accurate.

Surveys from other nations report even higher rates of serious abuse. In China, 14 percent of women experienced “severe physical abuse” (hitting, kicking, beating, strangling, choking, burning, or use of a weapon) in their lifetime, with 6 percent reporting such abuse in the past year (almost always at the hands of their husbands) (Xu et al., 2005). In Iran, women reported widespread abuse by their husbands, including physical abuse (44 percent), sexual abuse (31 percent), and psychological abuse (83 percent) (Vakili et al., 2010). When verbal abuse was included (hostile or insulting comments) a study of a New Zealand cohort of 25-

It is difficult to compare rates among nations, or even cohorts, since much depends on the survey questions, how they are asked, and to whom. For example, some studies of intimate partner violence among Hispanics in the U.S. report higher rates than among European Americans; other studies report lower rates (Cunradi, 2009). Both results are plausible. However, everyone agrees that the rates everywhere are much too high, that spouse abuse is almost the norm in some cultures, and that alcohol and drugs make violence more severe.

Traditionally, women, not men, were asked if they experienced domestic abuse because it was assumed that women were victims and men were abusers. It is true that more women are seriously injured or killed by male lovers than vice versa, evident in every hospital emergency room or police summary. However, when the definition of abuse includes threats, insults, and slaps as well as physical battering, some studies find more abusive women than men (Archer, 2000; Fergusson et al., 2005; Swan et al., 2008).

The original, mistaken male-

Social scientists have identified numerous causes of domestic violence, including youth, poverty, personality (such as poor impulse control), mental illness (such as antisocial disorders), and drug or alcohol addiction. Developmentalists note that many children who are harshly punished, sexually abused, or witness domestic assault grow up to become abusers or victims themselves. Neighborhood chaos is also a factor, as is the cultural acceptance of violence (Olsen et al., 2010).

Knowing these causes points toward prevention. Halting child maltreatment, for instance, averts some later abuse. It is also useful to learn more about each abusive relationship. Researchers differentiate two forms of partner abuse:

- situational couple violence

- intimate terrorism

564

Each of these has distinct causes, patterns, and means of prevention (M. P. Johnson, 2008; M. P. Johnson & Ferraro, 2000; Swan et al., 2008).

situational couple violence Fighting between romantic partners that is brought on more by the situation than by the deep personality problems of the individuals. Both partners are typically victims and abusers.

Situational couple violence occurs when both partners fight—

Situational couple violence can be reduced with maturation and counseling; both partners need to learn how to interact without violence. Often the roots are in the culture, not primarily in the individuals, which makes it possible for adults who love each other to learn how to overcome the culture of violence (Olsen et al., 2010).

intimate terrorism A violent and demeaning form of abuse in a romantic relationship, in which the victim (usually female) is frightened to fight back, seek help, or withdraw. In this case, the victim is in danger of physical as well as psychological harm.

Intimate terrorism is more violent, more demeaning, and more likely to lead to serious harm. Usually intimate terrorism involves a male abuser and female victim, although the sex roles can be reversed (Dutton, 2012). Terrorism is dangerous to the victim and to anyone who intervenes. It is also difficult to treat because the terrorist gets some satisfaction from abuse, and the victim often submits and apologizes. Social isolation makes it hard for outsiders to know what is happening, much less to stop it. With intimate terrorism, the victim needs to be immediately separated from the abuser, relocated in a safe place, and given help to restore independence.