19.3 Emerging Adults and Their Parents

It is hard to overestimate the importance of the family during any time of the life span. Although a family is composed of individuals, it is much more than the persons who belong to it. In the dynamic synergy of a well-

If anything, parents today are more important to emerging adults than ever. Two experts in human development write, “with delays in marriage, more Americans choosing to remain single, and high divorce rates, a tie to a parent may be the most important bond in a young adult’s life” (Fingerman & Furstenberg, 2012).

Linked Lives

Emerging adults set out on their own, leaving their childhood home and parents behind. They strive for independence. It might seem as if they no longer need parental support and guidance, but the data show that parents continue to be crucial. Fewer emerging adults than in the past have established their own families, secured high-

linked lives Lives in which the success, health, and well-

All members of each family have linked lives; that is, the experiences and needs of family members at one stage of life are affected by those at other stages (Macmillan & Copher, 2005). We have seen this in earlier chapters: Children are affected by their parents’ relationship, even if the children are not directly involved in their parents’ domestic disputes, financial stresses, parental alliances, and so on. Brothers and sisters can be abusers or protectors, role models for good or for ill.

The same historical conditions that gave rise to the stage now called emerging adulthood have produced stronger links between parents and their adult children. Because of demographic changes over the past few decades, most middle-

565

Especially for Family Therapists More emerging-

Response for Family Therapists: Remember that family function is more important than family structure. Sharing a home can work out well if contentious issues—

Many emerging adults still live at home, though the percentage varies from nation to nation. Almost all unmarried young adults in Italy and Japan live with their parents. Fewer do so in the United States, but many parents underwrite their young-

Strong links between emerging adults and their parents are evident in attitudes as well. A detailed Dutch study found substantial agreement between parents and their adult children on contentious issues: cohabitation, same-

Financial Support

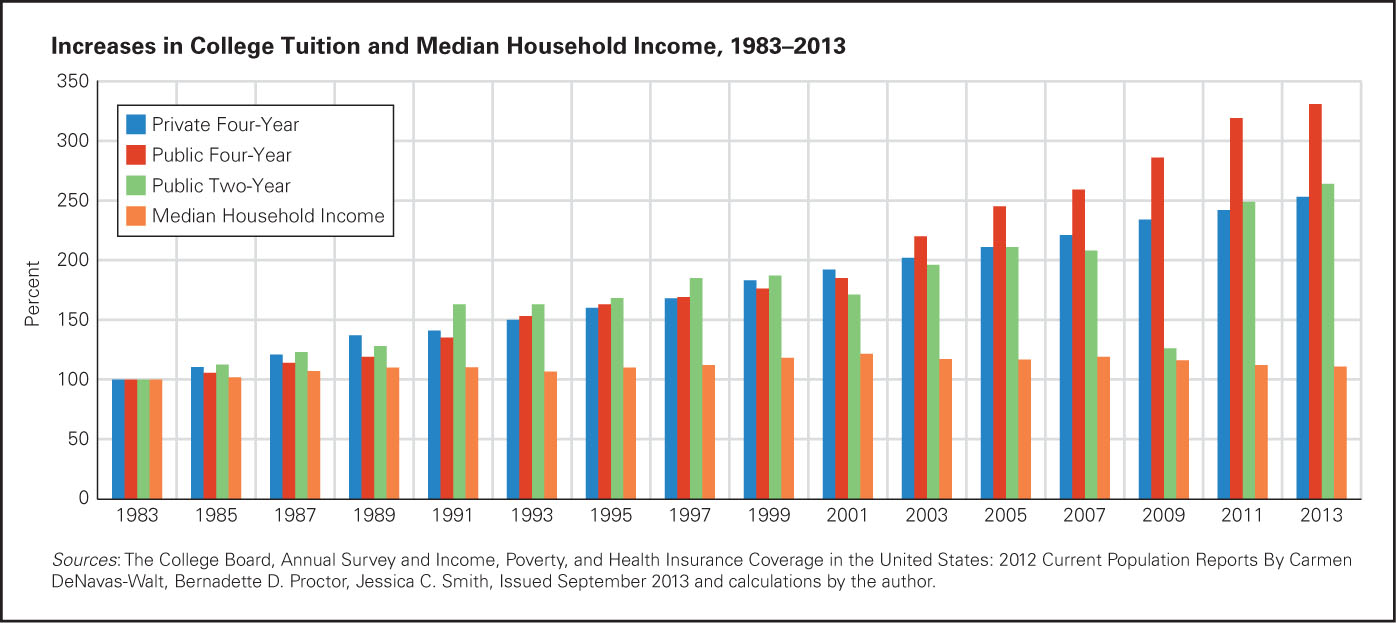

Parents of all income levels in the United States provide substantial help to their adult children, for many reasons. A major one is that the parent generation has more income. On average, households with the highest average income are headed by someone aged 45 to 54 (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2012). Often parents of emerging adults are employed, with some seniority, and are not yet paying for their own health or retirement. In nations such as the United States, where neither college nor preschool education is free, parental financial help may be crucial (Furstenberg, 2010).

This observation is not meant to criticize earlier cohorts; parents have always wanted to help their offspring. Now, however, more of them are able to give both money and time. For example, very few young college students pay all their tuition and living expenses on their own. Parents provide support; loans, part-

566

Cultural Differences

About one-

In most European nations college tuition is free or less expensive, early childhood education is considered a public right, and housing and health care are less costly. Accordingly, emerging adults in Europe are less likely to need parental financial support. However, parents support their adult children in many other ways—

Cultures differ in when and how families are destructive or helpful. For example, a study of enmeshment (e.g., parents involved in the thoughts and actions of their children) found that British emerging adults were less happy and successful when their parents were too intrusive. However, emerging adults in Italy seemed to remain close to their parents without hindering their own development (Manzi et al., 2006).

Some Westerners believe that family dependence is more evident in developing nations. There is some truth in this belief. For example, many African young adults marry someone approved by their parents and work to support their many relatives—

In cultures with arranged marriages, parents not only provide practical support (such as child care) and emotional encouragement, they may also protect their child. If the relationship is a disaster (for instance, the husband severely beats the wife, the wife refuses sex, the husband never works, or the wife never cooks), then the parents intervene. Again, each couple within each culture judges intervention differently: What is expected in, say, Cambodia, would be unacceptable in, say, Colorado.

567

Problems with Parental Support

Young adults from low-

helicopter parents The label used for parents who hover (like a helicopter) over their emerging adult children. The term is pejorative, but parental involvement is sometimes helpful.

There is a downside to parental support: It may impede independence. The most dramatic example is the so-

The rise in the number of college students living at home, or attending colleges near home, could be ascribed to financial concerns, and that certainly is part of it. But it also could result from parental reluctance to let go. Parents do many things for their emerging adult college students—

One mother explains that her son doesn’t come home from college as often as she would like, but when he does, he bring bags of dirty laundry that she washes and

I always send him back with some food and maybe a little bit of money as well…. I just feel he is my baby, and I feel as though I am still providing for him if I at least know he is eating right and has enough money.

[quoted in Kloep & Hendry, 2011, p. 84]

Parent assistance to emerging adults not only slows down maturation, it may create another problem. If a family has more than one child, the children may perceive favoritism. Often one sibling seems to receive more encouragement, money, or practical help from the parents. Differential treatment because of gender or age seems unfair to the less favored child.

In addition, mothers are more protective of a child who is emotionally dependent, and fathers seem more pleased with a more successful one. Interestingly, although most adults feel closer to their mothers than to their fathers, fathers are particularly influential for emerging adults, for good or ill (Schwartz et al., 2009).

From the parents’ perspective, each child has different needs, and that means different treatment. But such variations may not only be resented; they may reduce sibling closeness, increase conflict, and lead to depression, in the favored as well as the less favored child (Jensen et al., 2013).

Family involvement has many advantages, especially if the young adult becomes a parent and the new grandparents provide care. Free infant care from relatively young parents may be one reason why parenthood begins much earlier in poor nations. By contrast, parenthood before age 25 in the United States is a major impediment to higher education and career success, which may explain why emerging adults postpone it (Furstenberg, 2010).

568

Nationally and internationally, it is a mistake to put too much emphasis on whether or not a young adult still lives at home. Sharing living quarters is not the best indicator of a supportive relationship. Emerging adults who live independently but who previously had close relationships with their parents are as likely to avoid serious risks to their health and safety as those who never left.

As we think about the experiences of emerging adults overall, it is apparent that this stage of life has many pitfalls as well as benefits. These years may be crucial to long-

Fortunately, most emerging adults, like humans of all ages, have strengths as well as liabilities. Many survive risks, overcome substance abuse, combat loneliness, and deal with other problems through further education, maturation, friends, and family. If they postpone marriage, prevent parenthood, and avoid a set career until their identity is firmly established and their education is complete, they may be ready and eager for all the commitments and responsibilities of adulthood (described in the next chapters).

SUMMING UP

Intimacy needs are universal for all young adults, but specifics vary by culture and cohort. In developed nations in the twenty-

569