Understanding How and Why

Understanding How and Why

science of human development The science that seeks to understand how and why people of all ages and circumstances change or remain the same over time.

The science of human development seeks to understand how and why people—all kinds of people, everywhere, of every age—change over time. The goal of this science is for all 7 billion people on Earth to fulfill their potential. Growth is multidirectional, multicontextual, multicultural, multidisciplinary, and plastic, five terms that will soon be explained.

First, however, we need to emphasize that developmental study is a science. It depends on theories, data, analysis, critical thinking, and sound methodology, just like every other science. All scientists ask questions and seek answers in order to ascertain “how and why.”

Science is especially useful when we study people: Lives depend on it. What should pregnant women eat? How much should babies cry? When should children be punished? Under what circumstances should adults marry, or divorce, or retire, or die? People disagree, sometimes vehemently, because emotions, experiences, and cultures differ.

The Scientific Method

scientific method A way to answer questions that requires empirical research and databased conclusions.

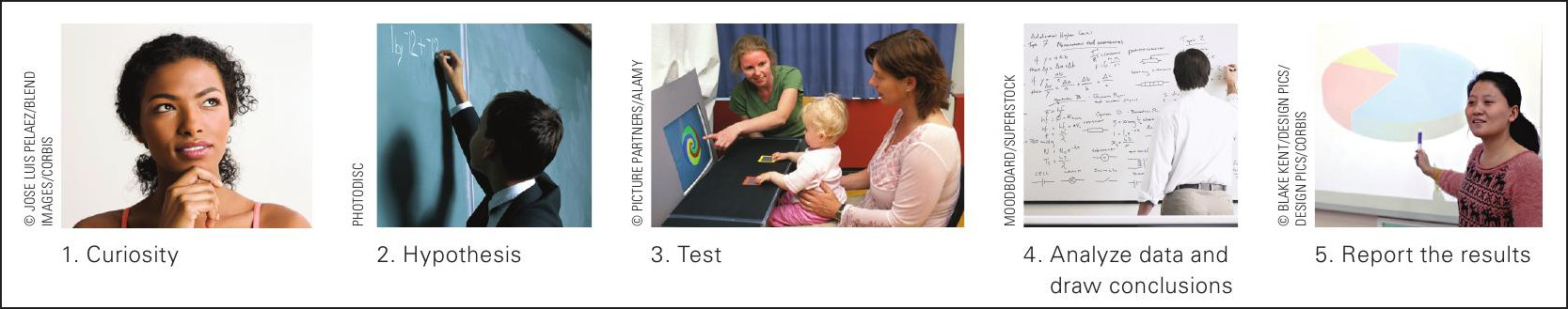

Facts may be misinterpreted and applications may spring from assumptions, not from data. To avoid unexamined opinions and to rein in personal biases, researchers follow the five steps of the scientific method (see Figure 1.1):

- Begin with curiosity. On the basis of theory, prior research, or a personal observation, pose a question.

- Develop a hypothesis. Shape the question into a hypothesis, a specific prediction to be examined.

hypothesis A specific prediction that can be tested.

- Test the hypothesis. Design and conduct research to gather empirical evidence (data).

empirical evidence Evidence that is based on observation, experience, or experiment, not theory.

- Analyze the evidence gathered in the research. Conclude whether the hypothesis is supported or not.

- Report the results. Share the data, conclusions, and alternative explanations.

FIGURE 1.1

Process, Not Proof Built into the scientific method—in questions, hypotheses, tests, and replication—is a passion for possibilities, especially unexpected ones.replication The repetition of a study, using different participants.

As you see, developmental scientists begin with curiosity and then seek the facts, drawing conclusions after careful research. Replication—repeating the procedures and methods of a study with different participants—may be a sixth and crucial step (Jasny et al., 2011).

Scientists study the reported procedures and results of other scientists. They read publications, attend conferences, send emails, and collaborate with others far from home. Conclusions are revised, refined, and confirmed after replication. Scientists still sometimes stray, drawing conclusions too quickly, misinterpreting data, or ignoring issues, as discussed at the end of this chapter. Nonetheless, testing hypotheses by gathering empirical data is the foundation of our study.

The Nature–Nurture Controversy

nature A general term for the traits, capacities, and limitations that each individual inherits genetically from his or her parents at the moment of conception.

nurture A general term for all the environmental influences that affect development after an individual is conceived.

An easy example of the need for science concerns a great puzzle of development, the nature–nurture debate. Nature refers to the influence of the genes that people inherit. Nurture refers to environmental influences, beginning with the health and diet of the embryo’s mother and continuing lifelong, including family, school, community, and societal experiences.

The nature–nurture debate has many other names, among them heredity–environment and maturation–learning. Under whatever name, the basic question is: How much of any characteristic, behavior, or emotion is the result of genes, and how much is the result of experience?

Some people believe that most traits are inborn, that children are innately good (“an innocent child”) or bad (“beat the devil out of them”). Others stress nurture, crediting or blaming parents, or neighborhood, or drugs, or even food, when someone is good or bad, a hero or a criminal.

Neither belief is accurate. The question is “how much,” not “which,” because both genes and the environment affect every characteristic: Nature always affects nurture, and then nurture affects nature. Even “how much” is misleading, if it implies that nature and nurture each contribute a fixed amount (Eagly & Wood, 2013; Lock, 2013).

A further complication is that the impact of a beating, or a beer, or any other experience might be magnified because of a particular set of genes. The opposite is true as well: Something in the environment—perhaps a poison, perhaps a blessing—might stop a gene before it could be expressed. Thus each aspect of nature and nurture depends on other aspects of nature and nurture, in ways that vary for each person.

The most obvious examples occur when a virus or a drug distorts the body or brain of a child. Less obvious, but probably more important, are protective influences, such as special nurturance that helps a person avoid learning disabilities or self-destructive impulses.

A complex nature–nurture interaction is apparent for every moment of our lives. For example, I fainted at Caleb’s birth because of at least ten factors (blood sugar, exhaustion, exertion, hormones, gender, age, family history, memory, relief, joy), each influenced by both nature and nurture. The combination, and no single factor, landed me on the floor.

SUMMING UP

The science of human development seeks to understand how and why each individual is affected by the changes that occur over the life span. Every science, including this one, follows five steps: question, hypothesis, empirical research, conclusions based on data, and publication. A sixth step—replication—confirms, refutes, or refines conclusions. Although no human is completely objective, the scientific method is designed to avoid unexamined opinions and wishful thinking.

Both genes and environment affect every human characteristic in an explosive interaction of nature and nurture. No human behavior—whether wonderful or horrific—results from genes or experiences alone.