Measuring Health

Measuring Health

Far more money is spent preventing death among people who are already sick (tertiary prevention) than on wellness before anyone gets sick. [Lifespan Link: The three levels of prevention are discussed in Chapter 8.]

In contrast, primary and secondary prevention are the goals of most public health workers and developmentalists. To measure the effectiveness of various efforts, four indicators are used: mortality, morbidity, disability, and vitality.

Mortality

mortality Death. As a measure of health, mortality usually refers to the number of deaths each year per hundred thousand members of a given population.

Death is the ultimate loss of health. Mortality is usually expressed as the annual number of deaths per hundred thousand in the population. The figure for various age, gender, and racial groups in the United States ranges from about 8 (Asian American girls aged 5 to 14 have 1 chance in 12,000 of dying within a year) to 15,640 (European American men over age 85 have about 1 chance in 6 of dying within a year) (National Center for Health Statistics, 2013).

To compare health among nations, age-

Mortality statistics are compiled from death certificates, which indicate age, sex, and immediate cause of death. This practice allows valid international and historical comparisons because deaths have been counted and recorded for decades—

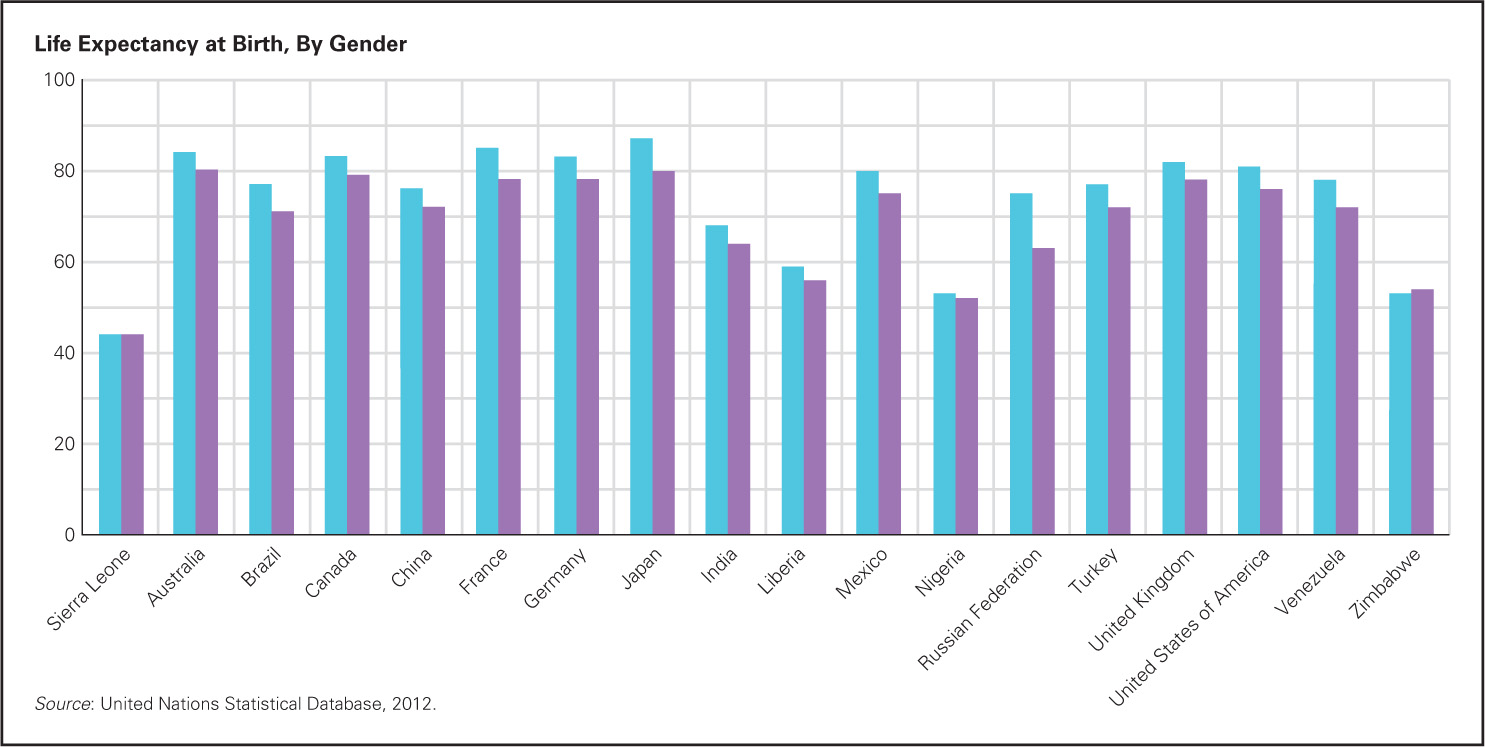

Mortality is lower for women (see Figure 20.4). Worldwide, women live 4 years longer than men, though that figure varies from place to place (United Nations, 2013). For example, men die an average of 13 years earlier than women in Russia (61 versus 74) but at the same age in Sierra Leone (both at 44). Worldwide, old women outnumber old men (by 2 to 1 at age 85), primarily because more young men and boys die. The sex ratio favors boys at birth, is about equal at age 50, and tilts toward women from then on (United Nations, 2013).

FIGURE 20.4

Not So Many Old Men International comparisons of life expectancy are useful for raising questions (why is the United States more similar to Mexico than to Japan?) and for highlighting universals (females live longer, no matter what their culture or health-Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2013).

This gender difference in mortality might be biological—

Men are socialized to project strength, individuality, autonomy, dominance, stoicism, and physical aggression, and to avoid demonstrations of emotion or vulnerability that could be construed as weakness. These [characteristics]…combine to increase health risks.

[D. R. Williams, 2003, p. 726]

Mortality rates also vary by ethnicity, income, and place of residence, within nations as well as between them. For example, the overall risk of dying for a U.S. resident at some point between ages 25 and 65 is about 15 percent, but for some it is as high as 50 percent (e.g., Sioux men in South Dakota) or less than 2 percent (Asian women in Connecticut) (Lewis & Bird-

Morbidity

morbidity Disease. As a measure of health, morbidity usually refers to the rate of diseases in a given population—

Another measure of health is morbidity (from the Latin word for “disease”), which refers to illnesses and impairments of all kinds—

Morbidity does not necessarily correlate with mortality. In the United States, almost half of older women have osteoarthritis; none die of it. Compared to men the same age, adult women have lower rates of mortality but higher rates of morbidity for almost every chronic disease.

Worldwide, as mortality decreases, morbidity increases. For instance, heart disease and cancer have been the leading causes of death for decades, but now they are also common causes of morbidity. The very measures that have saved lives—

A recent example is the PSA blood test for prostate cancer. Some research finds that screening adds a day to the average man’s life—

However, if a significant number of those 364 suffer from overdiagnosis, biopsies, and unnecessary surgery, producing increased morbidity (incontinence, impotence, crippling anxiety), then the screening was more destructive than beneficial. That is why the American Council of Physicians notes the “limited potential benefits and substantial harm of screening for prostate cancer” (Quaseem et al., 2013).

Likewise, mammograms for women under age 50 produce many false positives, and then needless biopsies and anxiety. Overall, when risks of both mortality and morbidity are considered, mammograms for many women may be more harmful than helpful (Woloshin & Schwartz, 2010).

Disability

disability Difficulty in performing normal activities of daily life because of some physical, mental, or emotional condition.

Disability refers to difficulty in performing “activities of daily life” because of a “physical, mental, or emotional condition.” Limitation in functioning (not severity of disease) is the hallmark of disability. Disability does not necessarily equal morbidity: In the United States, of the adults who are disabled, only 30 percent consider their health fair or poor (National Center for Health Statistics, 2013).

Normal activities, and hence ability to perform them, vary by social context. For example, people who cannot walk 200 feet without resting have a disability if their job requires walking (a mail carrier) but not if they sit at work (a post office clerk).

SCOTT EELLS/BLOOMBERG VIA GETTY IMAGES

DALYs (disability-

Disability-

Nonetheless, DALYs are useful in comparing nations and in examining trends. An analysis of DALYs in 21 regions of the world found that noncommunicable diseases are now the most common cause of disability, with heart disease first on the list (Murray et al., 2012). As communicable diseases (for example, malaria) have decreased, the DALYs of mental illness, especially depression, have increased. That means that, internationally, public health measures such as immunization have reduced diseases that one person catches from another, but economic and cultural stresses have increased psychological disability.

Vitality

vitality A measure of health that refers to how healthy and energetic—

The final measure of health, vitality, refers to how healthy and energetic—

For example, a study of older women in the United States with chronic diseases found that many felt energetic and vital, at least some of the time (Crawford Shearer et al., 2009). Vitality is affected more by personality and social affirmation than by biology. A longitudinal study of young adults who had been born weighing less than 3 pounds found that they were shorter and less athletic, and had higher risk of disease than a matched control group, but their vitality was as high as that of their peers (Baumgardt et al., 2011).

QALYs (quality-

One way to measure vitality is to calculate quality-

Calculating DALYs or QALYs helps in allocating public funds. No society spends enough to enable everyone to live life to the fullest. Without some equitable and calculable measure of disability and vitality, the best health care goes to whoever has the most money, or whatever tugs hardest at the public heartstrings.

This raises ethical issues. For example, should taxpayers subsidize kidney dialysis for young college students or intensive care for severely disabled 80-

That example is hypothetical; real choices are not that simple, and personal values push societies in directions that are not reflected in DALYs. Age is a factor: Many people think saving the life of a newborn is worth more than saving the life of a old person—

Individuals differ in how they value life, health, and appearance. As you read earlier, for some people, visibly growing older reduces their quality of life. They might avoid all social contact, and then temporarily lower their QALYs with cosmetic surgery, hoping to gain a higher quality of life. Other people would consider that foolish, because appearance does not impair their QALY.

This discussion leads to issues of public health and human development. If the focus is only on mortality and morbidity, prevention is tertiary (saving the seriously ill from dying) or secondary (spotting early symptoms). If the goal is less disability and more vitality, then factors (such as pollution, drug abuse, and global warming) that reduce QALY by a tiny bit for millions of people merit attention.

Correlating Income and Health

Money and education protect health. Well-

Perhaps education teaches healthy habits. Obesity and cigarette smoking in the United States are almost twice as common among adults with the least education compared to those with post-

For whatever reason, the differences can be dramatic. The 10 million U.S. residents with the highest SES (and the best health care) outlive—

SES has been shown to be protective of health in comparisons made both between and within nations. Compared to developing nations, rich countries have lower rates of disease, injury, and early death. For example, a baby born in 2010 in Northern Europe can expect to live to age 80; a baby born in central Africa can expect to live only to age 51 (United Nations, 2013).

Without doubt, low SES harms human development in every way, evident in statistics on mortality, morbidity, disability, and vitality. The data show that babies born poor are unlikely to escape their SES, as their education, health care, job prospects, and so on are all likely to work against them. They enter adulthood already impaired. Is there any hope?

That question returns us to Jenny, whose story began this chapter. When I first met her, she was among the poorest 10 million people in the United States, living in a Bronx neighborhood known as “Gunsmoke Territory” because of its high homicide rate. She was also African American (did you guess that from the sickle-

Observation Quiz The differences between the two scenes below are less about national culture than about neighborhood SES. What three signs suggest that the Brazilians are in a low-

Answer to Observation Quiz: The play space is smaller, the residences seem less elegant, and, most important, the Brazilians are shoeless—

MICHAEL REGAN/GETTY IMAGES

Her decision to have another baby—

But statistics do not reflect Jenny’s intelligence, creativity, and practical expertise. She applied what she learned. She knew she should be honest with Billy, and asked him to be tested for sickle cell (it was negative). She made her apartment “baby proof,” locking up the poisons, covering the electric outlets, getting her landlord to put guards on the windows.

She made the best of available government help. Her tuition was paid by a Pell grant, she lived in public housing, her children went to public schools, and she found parks and museums where her children could play and learn.

More important, she knew when and how to access social support, evidenced by her seeking me out. I saw her help her children with their homework, befriend their teachers, find speech therapy for her son, and provide love, supervision, and protection for all of them. After giving birth to a healthy, full-

When the baby was a little older, she went back to college, earning her B.A. on a full scholarship. Her professors recognized her intelligence and chose her to give the graduation speech. She then found work as a receptionist in a city hospital, a union job that provided medical insurance for her family. That allowed her to move her family to a safer part of the Bronx. While Jenny is exceptional, she is not unique: Some low-

Billy would sometimes visit her and the daughter he did not want, providing emotional and financial support. His wife became suspicious, hired a private investigator to follow him, and then delivered an ultimatum: Stop seeing Jenny or obtain a divorce. He chose Jenny. Soon after that, Billy married Jenny, and they moved to Florida.

Jenny continues to do well, though she has not completely escaped the toll of her early life (she developed diabetes, and must watch her diet carefully). But she bikes, swims, and gardens almost every day. She works full time in education, having earned a master’s degree. She and Billy seem happy together. Recently, I met the son who had a speech impediment: he had earned a PhD and is an assistant professor. Jenny’s daughters are college graduates.

This example might give the impression that escaping from poverty is easy; all the longitudinal data shows that it is not. Nor do most poor children thrive as Jenny’s children did. But the study of human development is not only about the contexts that affect each person. Each person is buffeted by all the habits, conditions, and circumstances described in this chapter, but each is also able to make choices that affect the future. The next chapter, on cognition in adulthood, describes some of those choices.

SUMMING UP

Health can be measured in at least four ways. Mortality is the easiest way to compare nations and cohorts, since keeping track of deaths is straightforward. Morbidity measures chronic illness, requiring diagnosis and ideally leading to treatment. Morbidity is more common in women than in men. Disability is indicated by difficulty performing daily tasks. Worldwide, disability is increasingly recognized as including psychological difficulties that make it hard to live a full life. Finally, vitality is the joy in living. Vitality is sought by everyone, affected by culture and personal choices, and may be independent of mortality and morbidity. SES within nations and among nations has a dramatic impact on health. Yet individuals sometimes find ways to overcome the strikes against them.