21.1 What Is Intelligence?

For most of the twentieth century, everyone—

604

As one scholar begins a book on intelligence:

Homer and Shakespeare lived in very different times, more than two thousand years apart, but they both captured the same idea: we are not all equally intelligent. I suspect that anyone who has failed to notice this is somewhat out of touch with the species.

[Hunt, 2011, p. 1]

general intelligence (g) The idea of g assumes that intelligence is one basic trait, underlying all cognitive abilities. According to this concept, people have varying levels of this general ability.

One leading theoretician, Charles Spearman (1927), proposed that there is a single entity, general intelligence, which he called g. Spearman contended that, although g cannot be measured directly, it can be inferred from various abilities, such as vocabulary, memory, and reasoning.

IQ tests had already been developed to identify children who needed special instruction, but Spearman promoted the idea that everyone’s overall intelligence could be measured by combining test scores on a diverse mix of items. A summary IQ number could reveal whether a person is a superior, typical, or slow learner, or, using labels of 100 years ago that are no longer used, a genius, imbecile, or idiot.

The belief that there is a g continues to influence thinking on intelligence (Nisbett et al., 2012). Many neuroscientists search for genetic underpinnings of intellectual capacity, although they have not yet succeeded in finding g (Deary et al., 2010; Haier et al., 2009). Some aspects of brain function, particularly in the prefrontal cortex, hold promise (Barbey et al., 2013; Roca et al., 2010). Many other scientists also seek one common factor that undergirds IQ—

Research on Age and Intelligence

Although psychometricians throughout the twentieth century believed that intelligence could be measured and quantified via IQ tests, they disagreed about interpreting the data—

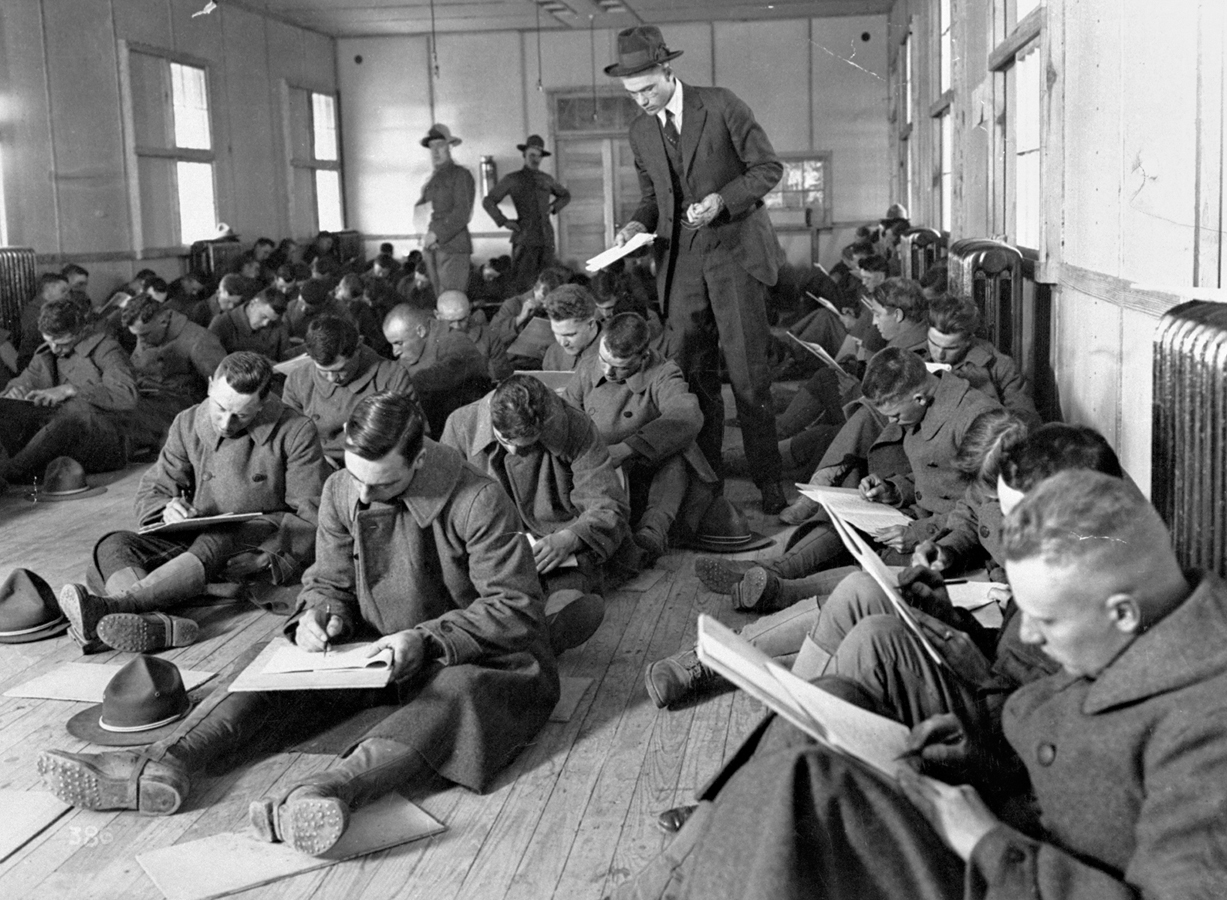

Observation Quiz Beyond the test itself, what conditions of the testing favored the younger men? (see answer, page 606]

Answer to Observation Quiz: Sitting on the floor with no back support, with a test paper at a distance on your lap, and with someone standing over you holding a stopwatch—

Cross-Sectional Declines

For the first half of the twentieth century, psychologists believed that intelligence increases in childhood, peaks in adolescence, and then gradually declines. Younger people were considered smarter than older ones. This belief was based on the best evidence then available.

For instance, the U.S. Army tested the aptitude of all draftees in World War I. When the scores of men of various ages were compared, it seemed apparent that intellectual ability reached its peak at about age 18, stayed at that level until the mid-

Hundreds of other cross-

605

Longitudinal Improvements

Shortly after the middle of the twentieth century, Nancy Bayley and Melita Oden (1955) analyzed the intelligence of the adults who had been originally selected as child geniuses by Lewis Terman decades earlier. Bayley was an expert in intelligence testing. She knew that “invariable findings had indicated that most intellectual functions decrease after about 21 years of age” (Bayley, 1966, p. 117). Instead she found that the IQ scores of these gifted individuals increased between ages 20 and 50.

Bayley wondered if their high intelligence in childhood somehow protected them from the expected age-

Why did these new data contradict previous conclusions? As you remember from Chapter 1, cross-

Earlier cross-

Powerful evidence that younger adults score higher because of education and health, not because of youth, comes from longitudinal research from many nations. Recent cohorts always outscore previous ones. As you remember from Chapter 11, this is the Flynn effect.

It is unfair—

Longitudinal studies are more accurate than cross-

- Repeated testing provides practice, and that itself may improve scores.

- Some participants move without forwarding addresses, or refuse to be retested, or die. They tend to be those whose IQ is declining, which skews the results of longitudinal research.

- Unusual events (e.g., a major war or a breakthrough in public health) affect each cohort, and more mundane changes—

such as widespread use of the Internet or less secondhand smoke— make it hard to predict the future based on the history of the past.

Will babies born today be smarter adults than babies born in 1990? Probably. But that is not guaranteed: Cohort effects might make a new generation score lower, not higher, than their elders. New data on the Flynn effect finds that generational increases have slowed down in developed nations, albeit not in developing ones (Meisenberg & Woodley, 2013). Thus health and educational benefits may be less dramatic for the next generation than they were 50 years ago.

606

Cross-Sequential Research

The best method to understand the effects of aging without the complications of historical change is to combine cross-

The Seattle Longitudinal Study

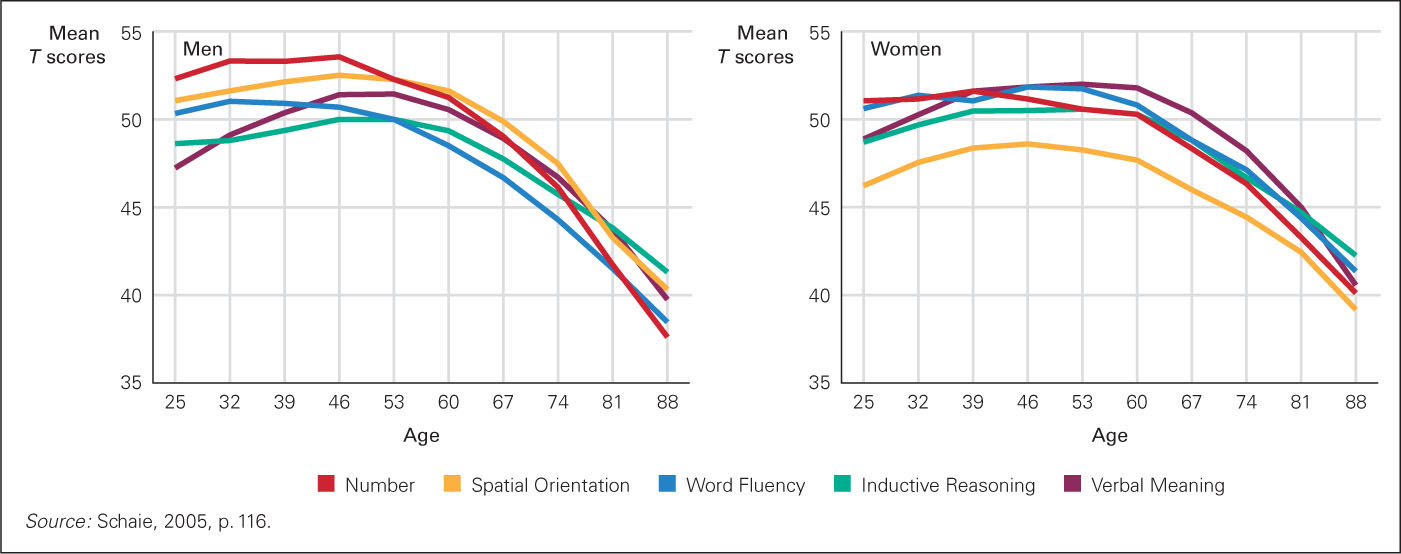

At the University of Washington in 1956, K. Warner Schaie tested a cross section of 500 adults, aged 20 to 50, on five standard primary mental abilities considered to be the foundation of intelligence: (1) verbal meaning (vocabulary), (2) spatial orientation, (3) inductive reasoning, (4) number ability, and (5) word fluency (rapid verbal associations). His cross-

Schaie then had a brilliant idea, to use both longitudinal and cross-

Seattle Longitudinal Study The first cross-

By retesting and adding a new group every seven years, Schaie obtained a more accurate view of development than was possible from either longitudinal or cross-

With cross-

607

Other researchers from many nations find similar trends, although the specific abilities and trajectories differ (Hunt, 2011). Adulthood is typically a time of increasing, or at least maintaining, IQ, with dramatic individual differences: Some people and some abilities show declines at age 40; others, not until decades later (Johnson et al., 2014; Kremen et al., 2014).

Especially for Older Brothers and Sisters If your younger siblings mock your ignorance of current TV shows and beat you at the latest video games, does that mean your intellect is fading?

Response for Older Brothers and Sisters: No. While it is true that each new cohort might be smarter than the previous one in some ways, cross-

Schaie discovered more detailed cohort changes than the Flynn effect. Each successive cohort (born at seven-

Another cohort effect is that the age-

One correlate of higher ability for every cohort is having work or a personal life that challenges the mind. Schaie found that recent cohorts of adults more often have intellectually challenging jobs and thus higher intellectual ability. That had a marked effect on female IQ, since women used to stay home or had routine jobs. Now that more women are employed in challenging work, women score higher than did women their age 50 years ago.

Other research also finds that challenging work fosters high intelligence. One team found that retiring from difficult jobs often reduced intellectual power, but leaving dull jobs increased it (Finkel et al., 2009). This depends on activities after retirement: Intellectually demanding tasks, paid or not, keep the mind working (Schooler, 2009; Schaie, 2013).

Many studies using sophisticated designs and statistics have supplanted early cross-

It is hard to predict intelligence for any particular adult, even if genes and age are known. For instance, a study of Swedish twins aged 41 to 84 found differences in verbal ability among the monozygotic twins with equal education. In theory, scores should have been identical, but they were not. As expected, however, age had an effect: Memory and spatial ability declined over time (Finkel et al., 2009).

Considering all the research, adult intellectual abilities measured on IQ tests sometimes rise, fall, zigzag, or stay the same as age increases. Specific patterns are affected by each person’s experiences, with “virtually every possible permutation of individual profiles” (Schaie, 2013, p. 497). This illustrates the life-

608

SUMMING UP

Intelligence as a concept is controversial, with some experts believing that there is one general intelligence, that individuals have more or less of it, and that each ability separately rises or falls. Psychometricians once believed that intelligence decreased beginning at about age 20: that is what cross-