Personality Development in Adulthood

Personality Development in Adulthood

A mixture of genes, experiences, and contexts results in personality, which includes each person’s unique actions and attitudes. Continuity is evident: Few people develop characteristics that are opposite their childhood temperament. But personality can change, usually for the better, as people overcome earlier adversity and confusion.

Theories of Adult Personality

To organize this mix of embryonic beginnings, childhood experiences, and adulthood contexts, we begin with theories.

Erikson and Maslow

Erikson originally envisioned eight stages of development, three after adolescence. He is praised as “the one thinker who changed our minds about what it means to live as a person who has arrived at a chronologically mature position and yet continues to grow, to change, and to develop” (Hoare, 2002, p. 3).

Erikson’s first four stages, already explained, are each tied to a particular chronological period. But adult stages do not occur in lockstep. Adults of many ages can be in the fifth stage, identity versus role confusion, or in any of the three adult stages—

| Unlike Freud or other early theorists who thought adults simply worked through the legacy of their childhood, Erikson described psychosocial needs after puberty in half of his eight stages. His most famous book, Childhood and Society (1963), devoted only two pages to each adult stage, but published and unpublished elaborations in later works led to a much richer depiction (Hoare, 2002). |

| Identity versus Role ConfusionAlthough Erikson originally situated the identity crisis during adolescence, he realized that identity concerns could be lifelong. Identity combines values and traditions from childhood with the current social context. Since contexts keep evolving, many adults reassess all four types of identity (sexual/gender, vocational/work, religious/spiritual, and political/ethnic). |

|

Intimacy versus IsolationAdults seek intimacy— |

| Generativity versus StagnationAdults need to care for the next generation, either by raising their own children or by mentoring, teaching, and helping others. Erikson’s first description of this stage focused on parenthood, but later he included other ways to achieve generativity. Adults extend the legacy of their culture and their generation with ongoing care, creativity, and sacrifice. |

| Integrity versus DespairWhen Erikson himself was in his 70s, he decided that integrity, with the goal of combating prejudice and helping all humanity, was too important to be left to the elderly. He also thought that each person’s entire life could be directed toward connecting a personal journey with the historical and cultural purpose of human society, the ultimate achievement of integrity. |

Similarly, Abraham Maslow (1954) refused to link chronological age and adult development when he described his five stages. Thus, people of many ages can be in Maslow’s third level (love and belonging, similar to Erikson’s intimacy versus isolation).

At that stage, the priority for people is to be loved and accepted by partners, family members, and friends. Without affection, people might stay stuck, needing love but never feeling that they have enough of it. They might ignore other needs in order to be loved. By contrast, those who experience abundant love are able to move to the next level, success and esteem. The dominant adult need at this fourth stage is to be respected and admired.

For humanists like Maslow, these five needs characterize all people, with most adults seeking love or respect (levels three and four), and a few reaching self-

Other theorists agree, sometimes describing affiliation and achievement, sometimes using other labels. We will use Erikson’s terms, intimacy and generativity, as a scaffold to describe these two universal needs. Every theory of adult personality recognizes both.

© RYAN MCGINNIS / ALAMY

The Midlife Crisis

No current theorist sets chronological boundaries for specific stages of adult development. Middle age, if it exists, can begin at age 35 or 50.

midlife crisis A supposed period of unusual anxiety, radical self-

This contradicts the notion of the midlife crisis, thought to be a time of anxiety and radical change as age 40 approaches. Men, in particular, were said to leave their wives, buy red sports cars, and quit their jobs. The midlife crisis was popularized by Gail Sheehy (1976), who called it “the age 40 crucible,” and by Daniel Levinson (1978), who said men experienced

tumultuous struggles within the self and with the external world. æ Every aspect of their lives comes into question, and they are horrified by much that is revealed. They are full of recriminations against themselves and others.

[Levinson, 1978, p. 199]

Especially for People in Their 20s Will future “decade” birthdays—

Response for People in Their 20s: Probably not. While many younger people associate certain ages with particular attitudes or accomplishments, few people find those ages significant when they actually live through them.

The midlife crisis continues to be referenced in popular movies, books, and songs. A 2013 Google search found more than 2 million hits, including a Wall Street Journal article about wealthy, successful, middle-

In hindsight, it is easy to see where they went astray. Levinson studied only 40 men, all from one cohort. The data were then analyzed by men who were also middle-

Even imperfect and limited data, however, might contain clues for new trends. Case studies and personal experiences may start scientists on a path of discovery. With the midlife crisis, however, every attempt at large-

Remember cohort effects. Middle-

No wonder these men were troubled. But their crisis was caused by personal reflections, family pressures, and historical circumstances, not by chronological age. Many adults, male or female, have moments when they question their earlier choices of career, or mate, or residence. Some make dramatic changes at age 30 or 40 or 50. However, few experience a classic midlife crisis.

Personality Traits

Remember from Chapter 7 that each baby has a distinct temperament. Some are shy, others outgoing; some are frightened, others fearless. Such traits begin with genes, but they are affected by experiences.

The Big Five

Temperament is partly genetic; it does not vanish. There are hundreds of examples, some of which are surprising. One recent study found, for instance, that temperament at age 3 predicted gambling addiction at age 32 (Slutske et al., 2012).

Big Five The five basic clusters of personality traits that remain quite stable throughout adulthood: openness, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism.

Longitudinal, cross-

- Openness: imaginative, curious, artistic, creative, open to new experiences

- Conscientiousness: organized, deliberate, conforming, self-

disciplined - Extroversion: outgoing, assertive, active

- Agreeableness: kind, helpful, easygoing, generous

- Neuroticism: anxious, moody, self-

punishing, critical

Each person’s personality is somewhere between extremely high and extremely low on each of these five. The low end might be described, in the same order as above, with these five adjectives: closed, careless, introverted, hard to please, and placid.

ecological niche The particular lifestyle and social context that adults settle into because it is compatible with their individual personality needs and interests.

Adults choose their social context, or ecological niche, selecting vocations, hobbies, health habits, mates, and neighborhoods in part because of personality traits. Personality affects almost everything, from whether a young adult develops an eating disorder to whether an older adult retires (Sansone & Sansone, 2013; Robinson et al., 2010).

Among the events, conditions, and attitudes linked to the Big Five are education (conscientious people are more likely to complete college), marriage (extroverts are more likely to marry), divorce (more often for neurotics), fertility (lower for women in recent cohorts who are more conscientious), IQ (higher in people who are more open), verbal fluency (again, openness and extroversion), and even political views (conservatives are less open) (Duckworth et al., 2007; Gerber et al., 2011; Jokela, 2012; Pedersen et al., 2005; Silvia & Sanders, 2010).

International research confirms that human personality traits (there are hundreds of them) can be grouped in the Big Five. Of course, personality and behavior are influenced by many other factors, not only by gender and cohort but also by culture. A test of the Big Five among a group in rural Bolivia—

Especially for Immigrants and Children of Immigrants Poverty and persecution are the main reasons some people leave their home for another country, but personality is also influential. Which of the Big Five personality traits do you think is most characteristic of immigrants?

Response for Immigrants and Children of Immigrants: Extroversion and neuroticism, according to one study (Silventoinen et al., 2008). Because these traits decrease over adulthood, fewer older adults migrate.

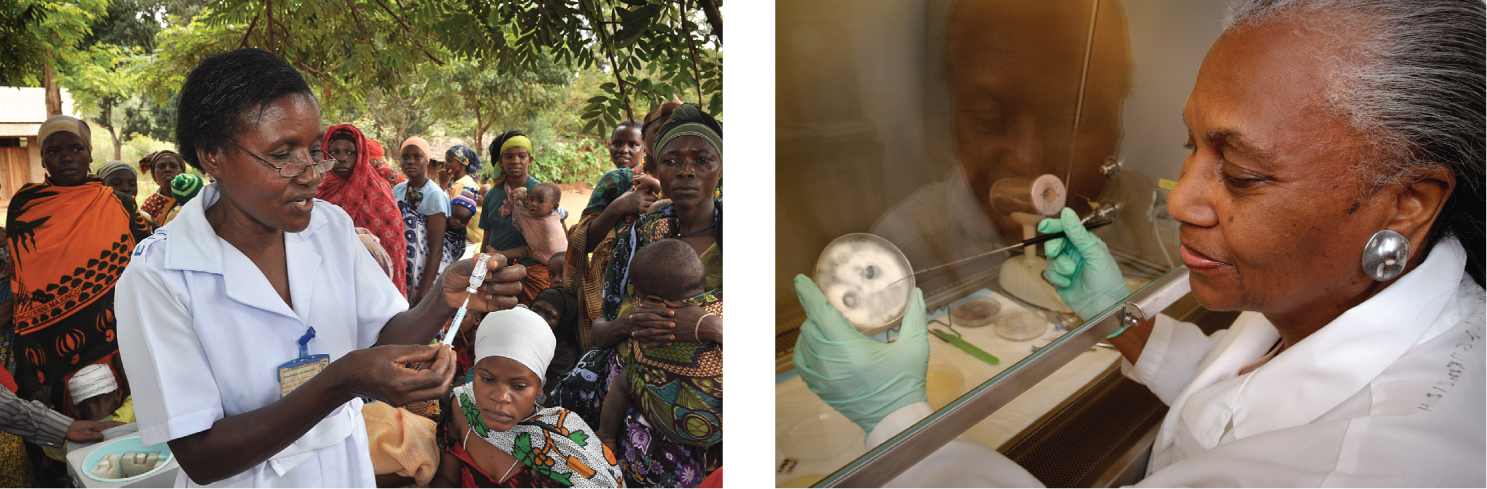

JAMES GATHANY/PHOTO RESEARCHERS/GETTY IMAGES

Age and Cohort

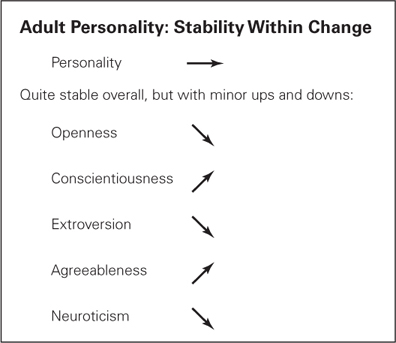

FIGURE 22.1

Trends, Not Rules Overall stability and some marked variation from person to person make up the main story for the Big Five over the decades of adulthood. In addition, each trait tends to shift slightly, as depicted here.Many researchers who study personality find that personality shifts slightly with age, but the rank order stays the same. In other words, those highest in extroversion at age 20 are still highest at age 80, compared to others their own age, although not necessarily compared to 20-

That is exactly what was found in a massive study of midlife North Americans (called MIDUS). Agreeableness and conscientiousness increased slightly overall while neuroticism decreased (Lachman & Bertrand, 2001) (see Figure 22.1). This pattern was also found in other research (Allemand et al., 2008; Donnellan & Lucas, 2008; Lehman et al., 2013).

Not surprisingly, then, self-

For both men and women born in 1920, those high in openness had about the same number of children as those low in that trait because the entire culture valued fertility. For those born in 1960, people high in openness had far fewer children than average. Their openness may have encouraged them to learn about family planning and overpopulation, and to consider non-

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

Local Context Versus Genes

Some people believe that personality is powerfully shaped by regional culture, so that a baby will have a quite different personality if born and raised, say, on the coast of Mexico or in the north of Canada. The opposite hypothesis is that personality is innate, fixed at birth and impervious to social pressures, with only minor, temporary impact from culture.

Evidence that personality is innate includes the fact that the same Big Five traits are found almost everywhere, with similar age trends. A 70-

Further evidence that personality is inborn rather than formed by culture is that each person usually has the same personality throughout adulthood. Personality changes, if they occur, happen more often early or late in life, not in the middle (Specht et al., 2011). Extroverted young adults become outgoing grandmothers with many friends from early adulthood and with more new friends each decade. Other traits likewise endure, sometimes changing a little but never reversing.

Nonetheless, some research finds that the environment affects personality, or, as one team wrote, “personality may acculturate” (Güngör et al., 2013, p. 713). One study compared the Big Five in three groups: Japanese, Japanese Americans, and European Americans. In general, the Japanese Americans were between the other two groups in self-

For example, in extroversion, the average among European Americans was highest, followed by the Japanese Americans and then the Japanese. Perhaps local conditions, such as the greater density of people per square mile in Japan than in the U.S., make the Japanese more likely to seek social harmony and therefore result in less extroversion.

Another study focused on extroversion in 28 countries and reported a curious correlation between self-

The idea that context shapes personality also comes from the Big Five scores of adults in the 50 U.S. states (Rentfrow et al., 2010). According to 619,397 respondents on an Internet survey, New Yorkers are highest in openness, New Mexicans highest in conscientiousness, North Dakotans highest in both extroversion and agreeableness, and West Virginians highest in neuroticism. Lowest in these five traits are, in order, residents of North Dakota, Alaska, Maryland, Alaska (again), and Utah.

This survey suggests that local norms, institutions, history, and geography have an impact. Let us hypothesize how this could be. Those who live in Utah are surrounded by Mormons (no drugs, large families, generally good health) and awesome mountains. That might make them less anxious, more serene, and thus lowest in neuroticism. This study found that many aspects of adults’ lives, including criminal behavior, morbidity, education, intelligence, and political preference, sprang from regional differences in personality (Rentfrow, 2008; Pesta et al., 2012).

Not only within the United States but also in England, physical surroundings seem to affect people. The English who lived near parks, gardens, and other greenery were less distressed. This study controlled for many factors, including age and income, and even traced people who moved from, or to, a plant-

Before concluding from this study that environment shapes personality, note the focus on distress, not personality. Do people who are less distressed also develop more agreeable, less neurotic personalities? Maybe. Or is distress superficial?

Someone who believes personality is innate might also question the U.S. data. Instead of people being affected by their surroundings, maybe people move to a community where their inborn traits are appreciated. For example, a North Dakotan college student who, unlike his neighbors, is genetically high in openness might relocate to New York. If people move to be with similar others, then regional differences would reflect personalities, not create them.

One review suggests that both nature and nurture are relevant, with the power of each affected by the age of the person. People under the age of 30 may seek an ecological niche—

A consensus regarding the relationship between culture, surroundings, genes, and personality has not yet emerged (Church, 2010). As you see, both opposing views are plausible. Which seems most accurate for you, your family, and friends? Do you “seek greener pastures” or “bloom where you are planted”? Does your culture affect your personality?

SUMMING UP

As all the theories of adult development describe, adults seek to have close friends and family as well as to be productive in society. Various theorists have many words for these needs: Erikson described intimacy and generativity, whereas Maslow wrote about love and belonging. Adult personality shows both continuity and change in reaction to life circumstances, and links to childhood temperament. The Big Five personality traits (openness, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism) are evident lifelong and worldwide. One reason for the continuity of traits is that adults choose their ecological niche: finding partners, jobs, communities, and life patterns that are compatible with their inborn temperament. On the other hand, the expression of personality can change during adulthood, usually for the better.