Intimacy: Romantic Partners

Intimacy: Romantic Partners

Social scientists often make a distinction between “family of origin” (the family each person is born into) and “family of choice” (the family one creates for oneself as an adult). Family of choice typically begins with a commitment to a romantic partner.

As detailed in the chapters on emerging adulthood, adults today take longer than previous generations did to publicly commit to one long-

Almost all U.S. residents born before 1940 married (96 percent). Fewer of those born between 1940 and 1960 married (89 percent), and a significant number of them are now divorced and not remarried (16 percent) (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2011a). Similar trends are found worldwide. Consider the data from Japan. Almost every Japanese adult was married in 1950, with many marrying before age 20. Now those Japanese who marry do so later (average age 30) and an estimated 20 percent will never marry (Raymo, 2013).

Marriage and Happiness

From a developmental perspective, marriage is a useful institution. Adults thrive if another person is committed to their well-

JOEL SATORE/NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC IMAGES

Especially for Young Couples Suppose you are one-

Response for Young Couples: There is no simple answer, but you should bear in mind that, while abuse usually decreases with age, breakups become more difficult with every year, especially if children are involved.

From an individual perspective, the consequences of marriage are more mixed. There is no doubt that a satisfying marriage improves health, wealth, and happiness, but some marriages are not satisfying (Fincham & Beach, 2010; Miller et al., 2013). Overall, married people are a little happier, healthier, and richer than never-

For this reason, it is misleading to lump all marriages together to find the average. Some marriages are very happy over the years, most marriages are moderately happy, and some marriages are not (see Figure 22.2). The least happy marriages do not always end with divorce—

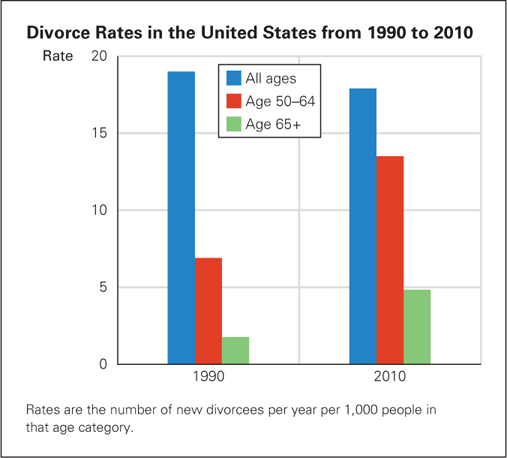

FIGURE 22.2

After All Those Years Newly married teenagers and emerging adults continue to be the groups most likely to divorce, but older married people are twice as likely to divorce as people their age were a few decades ago. In 1990 only one in ten newly divorced men or women was over age 50; now it is 1 in 4.

Many factors correlate with happiness, especially adequate income and college education. Factors that correlate with unhappiness are premarital births, prior cohabitation, and a high neuroticism on the Big Five personality inventory. Historically, women have had higher expectations for marriage and thus greater disillusionment, but that is changing by cohort and varies by culture (Stavrova et al., 2012). Women with more education and higher income are not only more likely to have happy marriages, they are “more likely to æ stay in good marriages and leave bad marriages” (Kreager et al., 2013, p. 580).

Partnership does not always mean marriage. Cohabiters who expect to marry are quite different from those who slide into living together because of convenience. If the latter couple eventually marries, their chances of a happy marriage are less than average. The same is true for couples who have sex within the first month of being together (Sassler et al., 2012). [Lifespan Link: Cohabitation is discussed on Chapter 19.]

Some couples cohabit as a step in commitment and mutual trust, fully intending to marry. Then each year of the marriage increases their public and personal commitment to each other and makes divorce less likely. Many signs indicate that such couples differ from those who drift into marriage. For instance, compared to less committed couples, they have more children, the man earns more than comparable unmarried men, and the wife spends more time on household tasks (Kuperberg, 2012).

A sizable number of adults have found a third way to have a steady romantic partner: living apart together (LAT). They have separate residences, but especially when the partners are older than 30, they may function as a couple for decades (Duncan & Phillips, 2010).

A couple’s decision to marry, to cohabit, or to LAT is influenced by many people in addition to the individuals who are romantically connected. Children born to an earlier partnership, even if those children are themselves adults, are particularly influential. Many parents choose to live apart from their partners because they do not want to upset their children (de Jong Gierveld & Merz, 2013).

Partnerships over the Years

The three boxes that questionnaires provide—

| Marital Happiness over the Years | ||

|---|---|---|

| Interval after Wedding | Characterization | |

| First 6 months | Honeymoon period— |

|

| 6 months to 5 years | Happiness dips; divorce is more common now than later in marriage | |

| 5 to 10 years | Happiness holds steady | |

| 10 to 20 years | Happiness dips as children reach puberty | |

| 20 to 30 years | Happiness rises when children leave the nest | |

| 30 to 50 years | Happiness is high and steady, barring serious health problems | |

| Not Always These are trends, often masked by more pressing events. For example, some couples stay together because of the children, so the empty nest stage becomes a time of conflict or divorce. | ||

My whole life I have been searching for love. At a personal level, after a number of false starts, I have found it. In my research—

[Sternberg, 2013, p. 98]

Since 1986, Sternberg has studied three aspects of love: passion, intimacy, and commitment, and many other scientists have explored that topic (Sternberg and Weiss, 2006). As explained in Chapter 17, currently passion is usually first, then shared confidences create intimacy, and finally commitment leads to an enduring relationship. When all three are evident, that is consummate love—

A wealth of research finds that for most people commitment is crucial. A long-

The passage of time also makes a difference. In general, the honeymoon period tends to be happy, but frustration increases as conflicts arise (see At About This Time) (H. K. Kim et al., 2008). Partnerships (including heterosexual married couples, committed cohabiters, same-

Remember, however, that averages obscure individual differences. Sometimes data is segmented by ethnicity. In the United States Asian Americans are much less likely to divorce than European Americans, and African Americans are more likely to do so. The ethnic differences are partly cultural and partly economic, making any broad effort to encourage marriage for everyone doomed to disappoint the politicians, social workers, and individuals involved (Johnson, 2012).

For cultural reasons, some unhappy couples stay married, and may have a long-

On the other hand, although cohabiting couples separate more often than married couples, some cohabitants are deeply committed to each other, happily raising children together. As always with development, trends and tendencies are useful to know, but not every individual follows them.

empty nest The time in the lives of parents when their children have left the family home to pursue their own lives.

Contrary to outdated impressions, the empty nest—when parents are alone again after the children have left—

Of course, time does not fix every relationship. Economic stress causes marital friction no matter how many years a couple has been together (Conger et al., 2010). Under the weight of major crises—

Gay and Lesbian Partners

Almost everything just described applies to gay and lesbian partners as well as to heterosexual ones (Biblarz & Savci, 2010; Cherlin, 2013; Herek, 2006). Some same-

Political and cultural contexts for same-

One finding seems particularly relevant for all partnerships. In every relationship, connections to family of origin remain important. The importance of family ties, quite apart from the legal benefits of marriage, is illustrated by same-

Although legal, moral, and financial arguments (health insurance, child rearing, and the like) are usually cited in public debate about same-

In a study of gay married couples in Iowa, one man decided to marry because, as he wrote about his mother: “I had a partner that I lived with æ and I think that, as much as she accepted him, it wasn’t anything permanent in her eyes” (Ocobock, 2013, p. 196). Another man wrote about his father: “He told us how proud of us he was that we were taking this step, and now he didn’t have three sons, he had four sons, and it was enough to make you cry” (p. 197).

In this study, most of the family members were supportive, but some were not—

Current and longitudinal research with a large, randomly selected sample of people in gay or lesbian marriages in the United States is not yet available. Many studies are designed to prove that same-

For example, some research says divorce is less common for same-

Divorce and Remarriage

Throughout this text, developmental events that seem isolated, personal, and transitory are shown to be interconnected, socially mediated, with enduring consequences. Relationships never improve or end in a vacuum; they are influenced by the social and political context. For example, a study of many nations found that the happiness as well as the likelihood of separation of married and cohabiting couples was powerfully influenced by national norms (most benign in Norway, most hostile in Romania) (Wiik et al., 2012).

Divorce occurs because at least one partner believes that he or she would be happier not married. That conclusion is reached fairly often in the United States: Since 1980, almost half as many divorces or permanent separations have occurred as marriages. (More than one-

Typically, people divorce because some aspects of the marriage have become difficult to endure. Often, however, they are unaware of the impact divorce will have. Among the future problems are reduced income, lost friendships, and weaker relationships with the children, immediately and when they grow up (Kalmijn, 2010; Mustonen et al., 2011).

Family problems arise not only with children (usually custodial parents become stricter, and noncustodial parents feel excluded) but also with other relatives. The divorced adult’s parents may be financially supportive, but often they are emotionally critical. Some married adults have good relationships with in-

For all these reasons, intimacy needs are less often met when couples separate. Sometimes divorced adults confide in their children, which may help the adults but not the children. Even if adults avoid that attractive trap, children need more emotional support just when the parents are often consumed by their own emotions (H. S. Kim, 2011).

Some research finds that women suffer from divorce more than men do (their income, in particular, is lower), but men’s intimacy needs are especially at risk. Some husbands rely on their wives for companionship and social interaction; they are unaccustomed to inviting friends over or chatting on the phone. Divorced fathers are often lonely, alienated from their adult children and grandchildren (Lin, 2008a).

Usually, both former partners in a severed relationship attempt to reestablish friendships and resume dating. About half of all U.S. marriages are remarriages for at least one partner. Remarriage is more common as SES rises, and less common among those who are already parents. Ethnicity is also a factor; in the United States, divorced African American mothers, especially those with less than a high school education, rarely remarry (McNamee & Raley, 2011).

Initially, remarriage restores intimacy, health, and financial security. For fathers, bonds with their new stepchildren or with a new baby may replace strained relationships with their children from the earlier marriage, a benefit for the men but not for the children (Noel-

Divorce usually increases depression and loneliness; repartnering brings relief. Most remarried adults are quite happy immediately after the wedding (Blekesaune, 2008). However, their happiness may not last. Because personality does not change much, people who were chronically unhappy in their first marriage often become unhappy in their second as well.

This research on divorce is sobering. As with all aspects of adult development, the shifting social context may have improved life for the formerly married, and even without that some people escape the usual patterns. If divorce ends an abusive, destructive relationship (as it does about one-

Furthermore, some divorces lead to stronger and warmer mother–

SUMMING UP

Family of origin (as distinct from chosen family) relationships usually remain important throughout adulthood as a source of social support, especially between parents and adult children and between siblings. Most adults seek, and find, a romantic partner who becomes an intimate companion. Each relationship follows its own path, but generally happiness ebbs and flows, with highs in the first months of a new relationship and lows when children are very young or teenagers. This is true for other-