22.4 Generativity

generativity versus stagnation The seventh of Erikson’s eight stages of development. Adults seek to be productive in a caring way, often as parents but, perhaps through art, caregiving, and employment.

According to Erikson, after the stage of Intimacy versus isolation comes that of generativity versus stagnation, when adults seek to be productive in a caring way. Without generativity, adults experience “a pervading sense of stagnation and personal impoverishment” (Erikson, 1963, p. 267). Adults satisfy their need to be generative in many ways, especially through parenthood, caregiving, and employment.

© SANDER DE WILDE/DEMOTIX/CORBIS

Parenthood

Although generativity can take many forms, its chief form is “establishing and guiding the next generation” (Erikson, 1963, p. 267). Many adults pass along their values as they respond to the hundreds of requests and unspoken needs of their children each day, thus becoming generative.

All the child accomplishments already explained in this text, from the Brazelton Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale (Chapter 4) to the first words (Chapter 6), from theory of mind (Chapter 9) to school achievement (Chapter 12), are celebrated by astute parents—

647

For example, knowing one particular baby is essential in interpreting those first mispronounced words and in reading those early emotional expressions. Similarly, knowing a child’s personality as well as intellectual prowess is required to find the zone of proximal development and then zeroing in on exactly when and how to help with schoolwork. In many ways, not only biological parents but also good foster parents are intensely committed to a particular, unique human being—

Biological Parenthood

The impact of parenting on children has been discussed many times in this text. Now we concentrate on the adult half of this interaction—

Most people underestimate how hard it is to be a good parent (Senior, 2014). Indeed, “having a child is perhaps the most stressful experience in a family’s life” (LeMasters, cited in McClain, 2011). Understandably, parenthood is particularly difficult when intimacy, not generativity, is a person’s primary psychosocial need. As already noted, marital happiness dips when the first baby arrives because intimacy needs must sometimes be postponed. Worse yet is having a baby as part of the search for identity, as teenagers discover too late.

Ideally, after establishing intimacy, many adults seek generativity, choosing parenthood, willingly coping with the many stresses that come with that role. Bearing and rearing children are labor-

Children may reorder adult perspectives as adults become less focused on their personal identity or intimate relationships. One sign of a good parent is the parent’s realization that the infant’s cries are communicative, not selfish, and that adults need to care for children more than vice versa (Katz et al., 2011).

Care can be expressed in many ways. A study of men and women who had been in the top .01 percent in math ability according to achievement tests administered when they were in high school, and who had earned graduate degrees decades later, found that both sexes were changed by parenthood. The fathers worked harder to achieve more status and income, while the mothers became more communal, focusing on community and family (Ferriman et al., 2009).

The dynamic experience of raising children tests every parent. Just when adults think they have mastered the art of parenting, children become a little older, presenting new challenges. Over the decades of family life, parents must adjust to new babies, school pressures, and teenage autonomy. Privacy and income almost never seem adequate, and almost every child needs extra care and attention at some point. A positive correlation between family size and family problems is apparent worldwide, at least until the children are grown (Margolis & Myrskylä, 2011).

An added joy and burden occurs when adult children have children themselves. Grandparenthood begins, on average, when adults are about age 50, and it continues for decades. [Lifespan Link: The complexities of grandparenthood are discussed in Chapter 25.]

648

Especially when children’s parents are troubled, grandparents worldwide believe their work includes helping their grandchildren (Herlofson & Hagestad, 2012). That becomes another source of generativity for them, affected by national policies and customs, gender, parent–

For the generativity of parenthood, biological parents have an advantage because they know they are intimately, genetically connected to their children. Especially if the pregnancy is intended (about one-

Roughly one-

Adoptive Parents

Compared to foster parents and stepparents, adoptive parents have several advantages: They are legally connected to their child for life, and they desperately wanted the child. Current adoptions are usually “open,” which means that the biological parents decided that someone else would be a better parent, yet they still want some connection to the child. The child knows about this arrangement, which proves an advantage for both sets of adults as well as for the child.

Strong parent–

However, some adopted children have spent their early years in an institution, never attached to anyone, which makes it more difficult for the adoptive parent. Some such children are afraid to love anyone (St. Petersburg–

As you remember, adolescence—

In attempts to upset my parents sometimes I would (foolishly) say that I wish I was given to another family, but I never really meant it. Still when I did meet my birth family I could definitely tell we were related—

[A, 2012, personal communication]

A longitudinal study of parent–

Attitudes in the larger culture often increase tensions between adoptive parents and children. For example, the mistaken notion that the “real” parents are the biological ones is a common social construction that hinders a secure relationship. International and interethnic adoptions are controversial because some people fear that such adoptions will result in children losing their heritage.

649

Adoptive parents who undergo the complications of international or interethnic adoption are usually intensely dedicated to their children. They are very much “real” parents, attempting to protect their children from discrimination that they might not have noticed before it affected their child. For example, one White couple adopted a mixed-

Many such adoptive parents seek multiethnic family friends and educate their children about their heritage and the prejudice they will likely face. Similar “racial socialization” often occurs within minority families for their biological children.

In fact, all parents seek to defend their children against the stresses of discrimination. When adoptive parents do so, their adolescents who encounter frequent prejudice (but not those who encounter less prejudice) experience less stress because their adoptive parents have prepared them (Leslie et al., 2013).

Stepparents

Parents of stepchildren often find the experience far more complicated than they had expected. The average new stepchild is 9 years old. Typically, he or she has spent some time with both biological parents, and then time with a single parent, a grandparent, their nonresident parent, other relatives, and/or a paid caregiver.

Changes are always disruptive for children (Goodnight et al., 2013), and the effects are cumulative, with many children typically erupting emotionally in adolescence. Becoming a stepparent to such a child, especially if the child is dealing with a change of schools, a change of friends, or the changes of puberty, is difficult. Children sometimes react to such changes by maintaining a strong, emotional attachment to their birth parents.

This reaction is normal and beneficial, but it hinders connections to stepparents. Any new adult who tries to be a child’s parent or friend and who simultaneously captures the love, care, and attention of the child’s biological parent is understandably suspect.

Stepmothers may hope to heal a broken family through love and understanding, whereas stepfathers may believe their new children will welcome a benevolent disciplinarian. Often the biological parent chose the new partner partly to give their children a better father or mother than the original one. The new stepparent may look forward to the role, in part because he or she learned about the other parent from a biased reporter, their new spouse. Both newlyweds may expect their stepchildren to respond well to the new family.

Children rarely fulfill these hopes. Often they are hostile or distant (Ganong, 2011). Young stepchildren get sick, lost, injured accidentally, or become disruptive in school; teenage stepchildren may get pregnant, drunk, or arrested. These are all signs that the child needs special attention—

Observation Quiz Which one is a stepchild?

Answer to Observation Quiz: Erika. There are two clues: The ages of the children make it more likely that the eldest is from the father’s first marriage, and biological children often try to grab their mother’s attention if she seems to focus on another child.

High hopes and expectations are common in new stepparents, but few adults—

650

Stepparents know that their connection to their stepchildren depends on their relationship with their new spouse, and they realize that criticizing the children or the way their mate relates to them may undercut their marriage. Some establish a good relationship with the children, although even if the marriage dissolves, as about half of all second marriages do, they will lose their connection to their stepchildren (Noel-

It is not surprising that stepchildren add unexpected stresses to a marriage (Sweeney, 2010). One theory is that because laws and norms are unclear about the role of stepparents, adults fight about what they expect each other to do or not do (Pollet, 2010). None of this means that stepparents cannot become generative; it does, however, warn of the many difficulties.

Foster Parents

Foster parents undertake the most difficult form of parenting of all and thus have the greatest opportunity for generativity. Foster children typically have emotional and behavioral needs that require intense involvement. Consequently, foster parents need to spend far more time and effort on each child than biological parents do, and yet the social context tends to devalue their efforts (Smith et al., 2013). Their reasons to become foster parents are more often psychosocial than financial (Geiger et al., 2013). Problems arise from both the context and the children.

First, let’s look at the situation. Although an estimated 400,650 children were in foster care in the United States in 2011 (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2013), sometimes saving them from severe abuse, the general public criticizes and demeans foster parents (Smith et al., 2013). Foster parents are paid for their care, but they typically earn far less than a babysitter or than they would in a conventional job. Most foster parents feel that they are not sufficiently prepared or supported in their role and are appalled at the publicity that focuses on the atypical foster home.

Further, most foster children are in their care for less than a year, as the goal for about half the children is reunification with the birth parent, with adoption planned for many others. Foster children are often moved from one placement to another, or from foster care back to the maltreating family, for reasons unrelated to the wishes, competence, or emotions of the foster parents. This makes it doubly hard for the foster parent to develop a generative attachment to their children, and doubly admirable when they do.

The children themselves add to the difficulty. The average child entering the foster care system is 7 years old (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2013). Many spent their early years with their birth families and are attached to them. Such human bonding is normally beneficial, not only for the children but also for the adults.

However, if birth parents are so neglectful or abusive that the children are seriously harmed by their care, the children’s early attachment to their birth parents impedes relationships with the foster parent. Furthermore, the children also know that their connection to their foster parent can be severed for reasons unrelated to caregiving quality or relationship strength. Since most foster children have experienced long-

As a result, adult caregivers of such children, either in foster families or institutions, face the dilemma of “whether to ‘love’ the children or maintain a cool, aloof posture with minimal sensitive or responsive interactions” (St. Petersburg–

651

Generative caring does not occur in the abstract; it involves a particular caregiver and care receiver, so everything needs to be done to encourage attachment between the foster parent and child. Adults who recognize developmental norms—

Caregiving

Caregiving is a lifelong process, as “life begins with care and ends with care” (Tally & Montgomery, 2013, p. 3). As just reviewed, parenting is a prime example, but not the only one.

As Erikson (1963) wrote, a mature adult “needs to be needed” (p. 266). Some caregiving requires meeting physical needs—

This is not simple, nor should it be taken for granted. As one study concludes:

The time and energy required to provide emotional support to others must be reconceptualized as an important aspect of the work that takes place in families. æ Caregiving, in whatever form, does not just emanate from within, but must be managed, focused, and directed so as to have the intended effect on the care recipient.

[Erickson, 2005, p. 349]

Thus, caregiving includes responding to the emotions of people who need a confidante, a cheerleader, a counselor, or a close friend. Parents and children care for one another, as do partners. Neighbors, friends, and distant relatives can be caregivers as well.

Kinkeepers

kinkeeper A caregiver who takes responsibility for maintaining communication among family members.

Most extended families include a kinkeeper, a caregiver who takes responsibility for maintaining communication. The kinkeeper gathers everyone for holidays; spreads the word about anyone’s illness, relocation, or accomplishments; buys gifts for special occasions; and reminds family members of one another’s birthdays and anniversaries (Sinardet & Mortelmans, 2009). Guided by their kinkeeper, all the family members become more generative.

Fifty years ago, kinkeepers were almost always women, usually the mother or grandmother of a large family. Now families are smaller and gender equity is more apparent, so some men or young women are kinkeepers.

Generally, however, the kinkeeper is still a middle-

Sometimes one family member is called on to do more than keep the family together. Because of their position in the generational hierarchy, middle-

sandwich generation The generation of middle-

Middle-

652

Far from being squeezed, older adults who provide some financial and emotional help to their adult children are less likely to be depressed than those adults whose children no longer relate to them (Byers et al., 2008). Meanwhile, those of the young adult generation, who are thought to be squeezing their parents, are caregivers themselves. Their care is not usually financial, but cultural. They help their parents understand music, media, and technology, programming their cell phones, sending electronic photos, fixing computer glitches.

As for caregiving from middle-

Shared caregiving keeps families together; wise kinkeepers typically make sure that happens.

Culture and Family Caregiving

The specifics of family bonds depend on many factors, including childhood attachments, cultural norms, and the financial and practical resources of each generation. Some cultures assume that elderly parents should live with their children; others believe that elders should live alone as long as possible and then enter some care-

Ethnic variations are evident in how interdependent family members are expected to be. Generally, ethnic minorities are more closely connected to family members than are ethnic majorities. They see each other more often, and they share food, money, child care, and so on. Although people may assume that closeness means affection, particularly for minorities closeness sometimes increases conflict (Voorpostel & Schans, 2011).

653

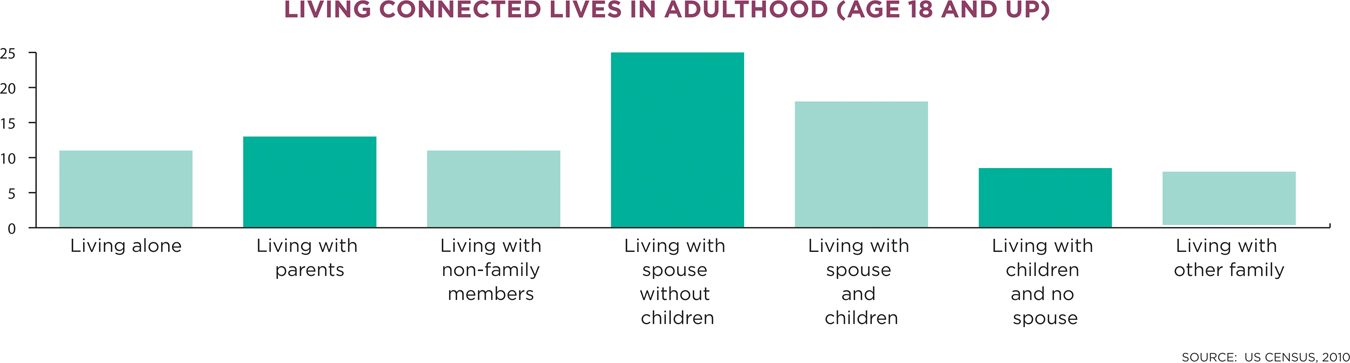

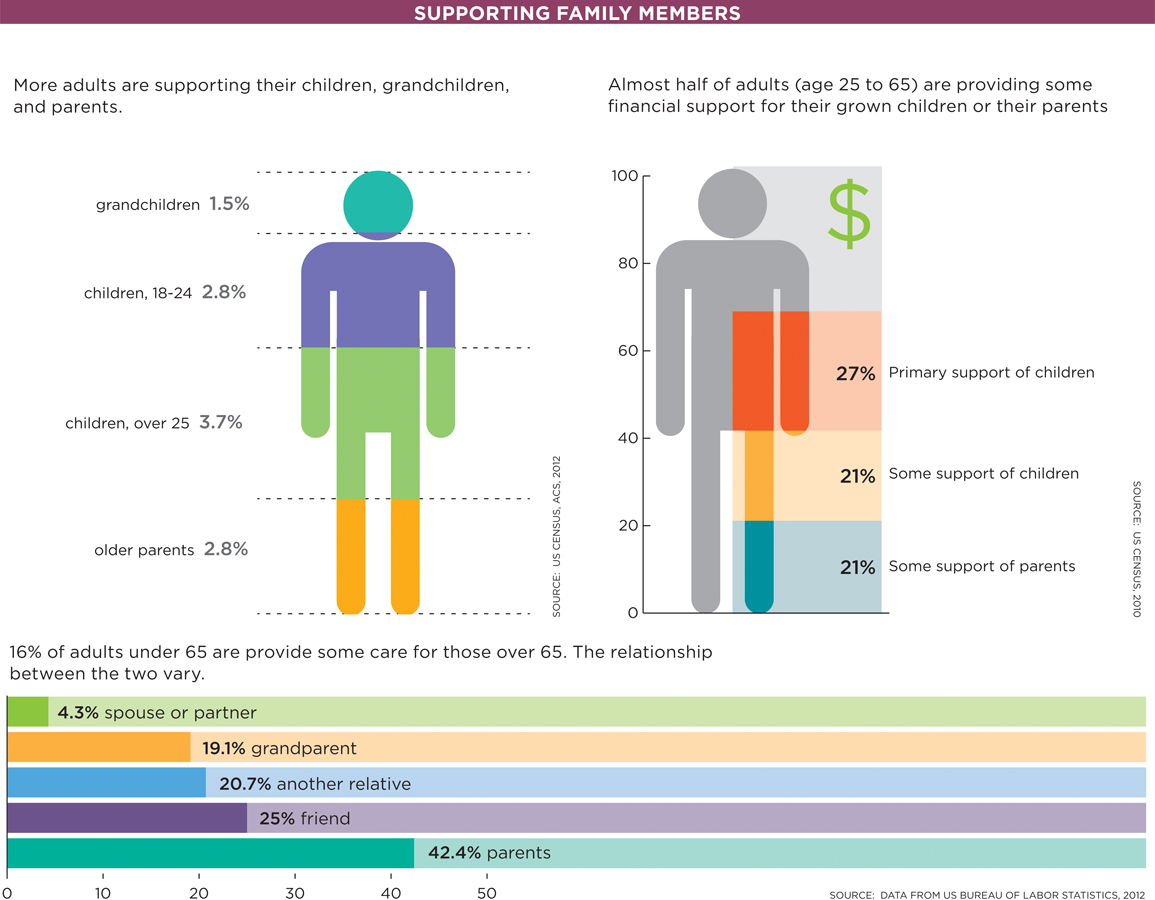

VISUALIZING DEVELOPMENTC

Caregiving in Adulthood

Longer life expectancies for elders and a challenging economy means that more adults than ever are meeting the needs of their aging parents, children, and even their grandchildren. While children account for most of the financial strain, caring for adult parents often involves the stresses, and rewards, of hands-

654

Cultures also differ as to whether sons or daughters are responsible for elder care. The assumption in traditional Asian nations is that sons provide for parents; this is unlike the assumption in most Western nations. However, the emphasis on caregiving sons (and daughters-

As you might imagine, if a husband and wife have divergent assumptions about elder care, or support for grown children, or mutual dependence, clashes may result. From a psychological perspective, adults are happier if they are caring for others, not just themselves, but how and when such caregiving occurs varies by individual, by family, and by culture.

Employment

Besides parenthood and caregiving, the other major avenue for generativity is employment. Most of the social science research on jobs has focused on economic productivity, an important issue but not central to our study of human development. Here we focus on the psychological costs and benefits of work during adulthood.

As is evident from many of the terms used to describe healthy adult development—generativity, success and esteem, instrumental, and achievement—

Wages and Benefits

Income pays living expenses, but it does far more than that. Beginning with Thorstein Veblen (1899/2008), sociologists have described conspicuous consumption, whereby people buy things—

Given this human characteristic, it is not surprising that raises and bonuses increase motivation. Surprisingly, though, the absolute income (whether a person earns $30,000 or $40,000 or even $100,000 a year, for instance) matters less than how a person’s income compares with others in their profession or neighborhood, or to their own salary a year or two ago. Salary cuts have emotional, not just financial, effects.

The sense of unfairness is innate and universal, encoded in the human brain (Hsu et al., 2008). Awareness of this fact helps explain some of the attitudes of adults about their pay. A detailed longitudinal study of nursing assistants who stayed or left their jobs over a one-

In the United States, many are offended by the extremely high salaries of corporate executives. That explains why the slogan, “We are the 99 percent,” had such power before the 2012 presidential election. Resentment arises not directly from wages, benefits, and working conditions but from how they are determined: If workers have a role in setting fair wages, they are more satisfied (Choshen-

655

It is part of human nature to believe other people are unfairly advantaged. Women complain that men are better paid, members of one ethnic group may resent other groups for their income or benefits, some younger workers resent the seniority of older workers who themselves may complain that the young are less dedicated, and so on. This is not to deny that discrimination exists: All these complaints arise from reality as well as from human nature, but part of the human mind seems hypersensitive to perceived inequality.

A related problem is that people want to hold onto whatever they have rather than risk losing it for something better (Kahneman, 2011). This characteristic, called risk aversion, explains why seniors who receive medical care paid by the government (Medicare) are fiercely protective of that benefit and fear that extending that same benefit to younger adults might diminish their own care. Any change in employment conditions that benefits many people but harms a few is likely to be resisted by the few more than welcomed by the many.

To understand human development, we must go beyond income and consider also the generative aspects of work—

Work provides a structure for daily life, a setting for human interaction, a source of social status and fulfillment. In addition, work meets generativity needs by allowing people to do the following:

- Develop and use their personal skills.

- Express their creative energy.

- Aid and advise coworkers, as mentor or friend.

- Support the education and health of their families.

- Contribute to the community by providing goods or services.

extrinsic rewards of work The tangible benefits, usually in the form of compensation (e.g., salary, health insurance, pension), that one receives for doing a job.

intrinsic rewards of work The intangible gratifications (e.g., job satisfaction, self-

These facts highlight the distinction between the extrinsic rewards of work (the tangible benefits such as salary, health insurance, and pension) and the intrinsic rewards of work (the intangible gratifications of actually doing the job). Generativity is intrinsic.

The power of these rewards may be affected by age. Extrinsic rewards tend to be more important when young people are first hired (Kooij et al., 2011). After a few years, in a developmental shift, the “intrinsic rewards of work—

The power of intrinsic rewards explains why older employees are, on average, less frequently absent or late and more committed to doing a good job than younger workers are (Landy & Conte, 2007). They also have more control over what they do, as well as when and how they do it. The autonomy that often comes with age reduces strain and increases dedication.

Employers, however, seem to favor younger workers—

656

The Changing Workplace

Obviously, work is changing in many ways that affect adult development. We focus here on only three—

Fifty years ago, the U. S. civilian labor force was 74 percent male and 89 percent non-

This increased diversity is also apparent within occupations. For example, in 1960 male nurses and female police officers were very rare, perhaps 1 percent. Now 13 percent of registered nurses are men and 9 percent of police officers are women—

This change benefits millions of adults who would have been jobless in previous decades, but it also requires workers and employers to be sensitive to differences they did not notice. Younger adults may have an advantage because they are more likely to accept diversity—

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

Accommodating Diversity

Accommodating the various sensitivities and needs of a diverse workforce requires far more than reconsidering the cafeteria menu and the holiday schedule. Private rooms for breast-

Certain words, policies, jokes, or mannerisms may seem innocuous to one group but hostile to people of another group. For example, women object to sexy pin-

Micro-

Comments about “senior moments” or being “color-

657

The second change is in employment stability. Today’s workers change jobs more often than workers did because resignations, firings, and hirings occur more often. Employers constantly downsize, reorganize, relocate, outsource, or merge. Loyalty between employee and employer, once heralded, seems quaint.

This flexibility of the job market may increase corporate profits, worker benefits, and consumer choices. However, churning employment affects human development, not usually for the better. Work friendships are disrupted and stress increases with every change. One study found that people who frequently changed jobs by age 36 were three times more likely to have health problems by age 42 (Kinnunen et al., 2005). This study controlled for smoking and drinking; if it had not, the health impact would have been greater.

As adults grow older, losing a job becomes increasingly stressful for several reasons (Rix, 2011):

- Seniority brings higher salaries, more respect, and greater expertise; workers who leave a job they have had for years lose these advantages.

- Many skills required for employment were not taught decades ago, so older job seekers are less likely to be hired.

- Age discrimination is illegal, but workers believe it is widespread. Even if it does not exist, stereotype threat undercuts successful job searching.

- Relocation reduces long-

standing intimacy and generativity.

From a developmental perspective, this last factor is crucial. Imagine that you are a 40-

If you were unemployed and in debt, and a new job was guaranteed, you might make the move. You would leave your friends and community, but at least you would have a paycheck. But would your spouse and children quit their jobs, schools, and social networks to move with you? If not, you would be cut off from all your social support, but if they did, their food and housing would be expensive, their schools would be overcrowded, and their lives would be lonely (at least initially). For you and anyone who comes with you, moving means losing intimacy—

© JOHN BOYKIN/PHOTOEDIT

658

Such difficulties are magnified for immigrants, who make up about 15 percent of the U.S. adult workforce and 22 percent of Canada’s. Many of them depend on other immigrants for housing, work, and social support (García Coll & Marks, 2012). That meets some of their intimacy and generativity needs, but their connections to their family of origin and friends are strained by distance; the climate, the food, and the language are not comforting.

These developmental needs are ignored by many business owners and workers themselves. Adults’ intimacy and generativity needs are met by a thriving social network; without that, psychological and physical health suffer.

Work Schedules

Especially for Entrepreneurs Suppose you are starting a business. In what ways would middle-

Response for Entrepreneurs: As employees and as customers. Middle-

No longer does work always follow a 9-

One crucial variable for job satisfaction is whether employees can choose their own hours. Workers who volunteer for paid overtime are usually satisfied, but workers who are required to work overtime are not (Beckers et al., 2008). This is true no matter how experienced the workers are, what their occupation is, or where they live.

For instance, a nationwide study of 53,851 nurses, ages 20 to 59, found that required overtime was one of the few factors that reduced job satisfaction in every cohort (Klaus et al., 2012). Similarly, a study of office workers in China also found that the extent of required overtime correlated with less satisfaction and poorer health (Houdmont et al., 2011). Apparently, although work (paid or unpaid) is satisfying to every adult, working too long and not by choice undercuts the psychological and physical benefits.

Weekend work, especially with mandatory overtime, is particularly difficult for father—

In theory, part-

About one-

Combining Intimacy and Generativity

A large study of adult Canadians found that about half of the variation in their distress was related to employment (working conditions, support at work, occupation, job security), but at least as much was related to family issues (having children younger than 5, support at home) and feelings of personal competence (Marchand et al., 2012).

659

To find an ideal balance, at least three factors are helpful: adequate income, chosen schedules, and social support. As an example of linked lives, husbands and wives usually adjust to each other’s needs, which allows them to function better as a couple even than they did as singles (Abele & Volmer, 2011). For instance, after marriage men spend, on average, more hours on the job and women more hours on the home. As a result, five years after marriage the man’s salary is notably higher than it would have been if he were single, while their shared home is notably more accommodating (Kuperberg, 2012).

If they have children, couples adjust their work and child-

Perhaps men, women, and children are better off with today’s dual-

At the same time, many couples feel overwhelmed with the simultaneous demands of parenting and employment. Often they postpone births; often the mother is employed sooner or more extensively than she would wish. This varies by nation, with government policies regarding maternity leave, child care, and health insurance influential in people’s decision making (Lyonette et al., 2011; Nieuwenhuis et al., 2012).

Overall, it is debatable whether adults fare better or worse in today’s economic climate and with today’s social norms. Diversity, job change, and flexible schedules have benefits as well as costs. Maternal employment is more likely to benefit families than not, but children still need parental attention—

BRIAN CASSELLA/ZUMA PRESS/NEWSCOM

Because personality is enduring and variable, opinions about current adult development reflect personality as well as objective research. Some people are optimists—

660

The data support both perspectives—

As the next three chapters detail, there are many possible perspectives on life in late adulthood as well. Some view the last years of life with horror, others consider them the golden years. Neither view is quite accurate, as you will soon see.

SUMMING UP

Adults strive to meet their generativity needs, primarily through raising children, caring for others, and being productive members of society. Parenthood of all kinds is difficult yet rewarding, with foster, step-

Employment ideally aids generativity through productivity and social networks. Diversity and flexibility characterize the current job market. Many young parents work nonstandard schedules, which disrupts family life. Many parents combine child rearing and employment, with mixed success.

661