Prejudice and Predictions

Prejudice and Predictions

ageism A prejudice whereby people are categorized and judged solely on the basis of their chronological age.

Prejudice about late adulthood is common among people of all ages, including young children and older adults. That is a reflection of ageism, the idea that age determines who you are. Stereotyping makes ageism “a social disease, much like racism and sexism … [causing] needless fear, waste, illness, and misery” (Palmore, 2005, p. 90).

Ageism can target people of any age, but it is not recognized as readily as racism or sexism. Consider curfew laws that require every teenager to be off the streets by 10 P.M.: that is ageist. Imagine the outcry if a curfew targeted all non-

One expert contends that

there is no other group like the elderly about which we feel free to openly express stereotypes and even subtle hostility…. Most of us … believe that we aren’t really expressing negative stereotypes or prejudice, but merely expressing true statements about older people when we utter our stereotypes (Nelson, 2011, p. 40).

Nelson believes that ageism is institutionalized in our culture and has become pervasive in the media, employment, and retirement communities.

Another reason people accept ageism is that it often seems complimentary (“young lady”) or solicitous (Bugental & Hehman, 2007). However, the effects of ageism, whether benevolent or not, are insidious, seeping into and eroding the older person’s feelings of competence. The resulting self-

Believing the Stereotype

Parents protect their children from racism via racial socialization, teaching them to recognize and counter bias while encouraging them to be proud of who they are. However, when children express an ageist thought, few people teach them otherwise. Later on, their long-

For example, in one study, adults younger than age 50 expressed opinions about the elderly, such as agreeing or not that “old people are helpless.” Thirty years later, those who were least ageist were half as likely to have serious heart disease compared to those who were most ageist (Levy et al., 2009). Attitudes about aging vary from culture to culture, with deadly consequences.

SEONGJOON CHO/LONELY PLANET IMAGES/GETTY IMAGES

Attitudes toward aging may be one reason longevity varies markedly depending on where a person lives. (The estimated life span for people born in various nations was shown in Figure 20.4). Japan has the highest life expectancy in the world—

Many contend, however, that ageism is now prevalent worldwide, even in Japan (North & Fiske, 2012). Perhaps only nations with few old people can afford to venerate them.

Ageist Elders

Ageism becomes a self-

If the elderly attribute their problems to the inevitability of age, they will not try to change themselves or the situation. For example, if they forget something, they laugh it off as a “senior moment,” not realizing the ageism of that reaction. When hearing an ageist phrase—

Asked how old they feel, typical 80-

It is illogical for all the 80-

Stereotype threat can be as debilitating for the aged as for other groups (Hummert, 2011). [Lifespan Link: Stereotype threat was discussed in detail in Chapter 18.] If the elderly fear they are losing their minds, that fear itself may undermine cognitive competence (Hess et al., 2009). Internalized ageism is much worse than an ageist comment from someone else, as the following view from science illustrates.

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

When You Think of Old People …

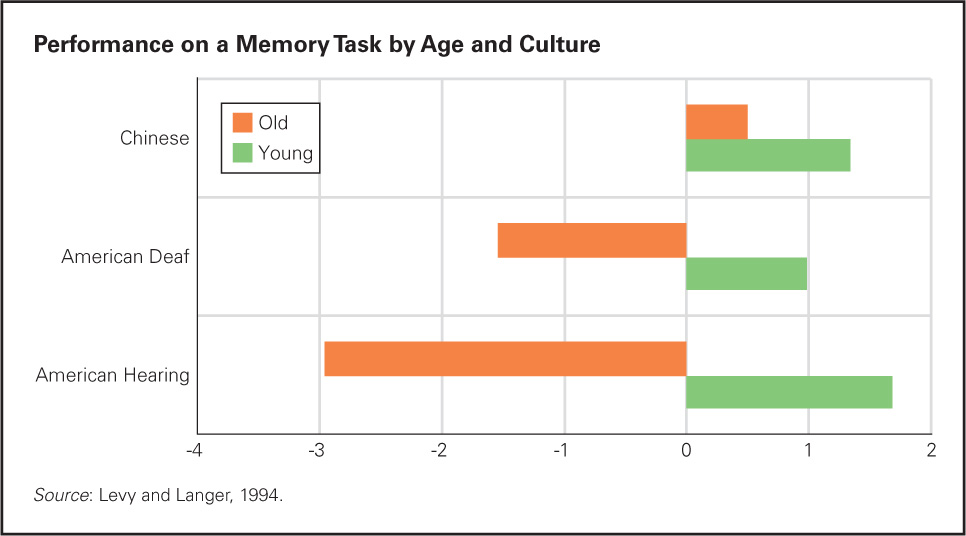

The effect of internalized ageism was apparent in a classic study (Levy & Langer, 1994). The researchers selected three groups. Two were thought to be less exposed to ageism: residents of China, where the old were traditionally venerated, and North Americans who were deaf lifelong. The third group was composed of North Americans with typical hearing, who presumably had heard ageist comments all their lives. In each of these three groups, half the participants were young and half were old.

Memory tests were given to everyone, six clusters in all. Elders in all three groups (Chinese, deaf Americans, and hearing Americans) scored lower than their younger counterparts. This was expected; age differences are common in laboratory tests of memory, as will be explained in detail in Chapter 24.

The purpose of this study, however, was not to replicate earlier research, but to see if ageism affected memory. It did. The gap in scores between younger and older hearing North Americans (most exposed to ageism) was double that between younger and older deaf North Americans and five times wider than the age gap in the Chinese (see Figure 23.1). Ageism undercut ability, a conclusion also found in many later studies (Levy, 2009).

FIGURE 23.1

The Widest Gap The bars show how the six groups score on a memory test, with the overall average right in the middle, at 0. Age slows down memory—Sadly, later studies have found that modernization has made many Asian cultures more ageist than they used to be (Chen & Powell, 2012; Nelson, 2011). And numerous studies continue to find that an older person’s attitude about aging affects, for good or ill, their mental performance, social life, and even physical health.

For example, positive concepts of aging correlate with faster recovery from disability (Levy et al., 2012). This study began with 598 healthy people age 70 or older, followed for more than 10 years. Initially they were asked, “When you think of old persons, what are the first five words or phrases that come to mind?” Their answers were rated from most negative (e.g., decrepit, demented) to most positive (e.g., wise, spry). From this a score of attitudes was calculated for each person.

Over the years of the study, many of the participants experienced disabilities, including some so severe that they temporarily could not walk, feed themselves, go to the toilet, or even get out of bed. Some had major surgery or were hospitalized, sometimes requiring intensive care. Then most recovered, at least somewhat. Their resilience depended partly on other illnesses, on income, and on many other factors, as one might predict.

However, when all those factors were taken into account, how quickly and completely people recovered from disability was affected by their earlier attitudes about the old. The most dramatic difference was found in those people who experienced severe disabilities: Compared to those with the most negative stereotypes, those with positive associations about aging became completely independent again 44 percent more often (Levy et al., 2012).

When older people believe that they are independent and in control of their own lives, they are likely to be healthier—

Sleep and Exercise

Ageism impairs the routines of daily life. It prevents depressed older people from seeking help because they resign themselves to infirmity.

Ageism also leads others to undermine an elder’s vitality and health. For instance, health professionals are less aggressive in treating disease in older patients, researchers testing new prescription drugs enroll few older adults (who are most likely to use those drugs), and caregivers diminish independence by helping the elderly too much (Cruikshank, 2009; Herrera, 2010; Peron & Ruby, 2011–

One specific example is sleep. The day–

In one study, older adults complaining of sleep problems were mailed six booklets (one each week) (Morgan et al., 2012). The booklets described normal sleep patterns for people their age and gave suggestions to relieve insomnia. Compared to similar older people who did not get the booklets, the informed elders used less sleep medication and reported better quality sleep. Even 6 months after the last booklet, they were more satisfied with their sleep.

The booklets told elders what to do about their sleep. For uninformed elders, ageism can lead to distress over normal sleep; doctors might prescribe narcotics, or people might drink alcohol. These remedies can overwhelm an aging body, causing heavy sleep, confusion, nausea, depression, and unsteadiness.

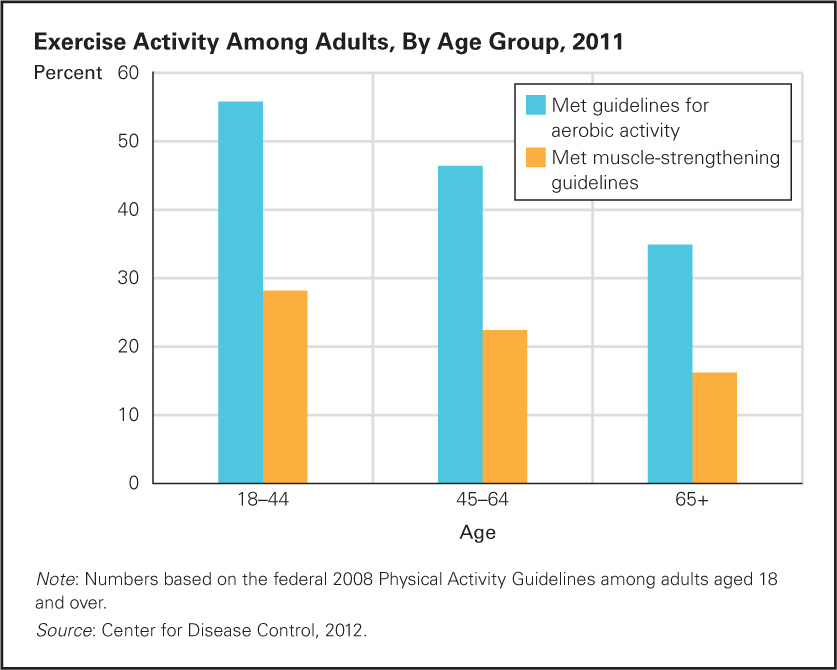

A similar downward spiral is apparent with regard to exercise. In the United States, only 35 percent of those over age 64 meet the recommended guidelines for aerobic exercise, compared with 56 percent for adults aged 18 to 44 (National Center for Health Statistics, 2013) (see Figure 23.2). Meeting the guidelines for muscle strengthening was worse; only 16 percent of the aged did so.

FIGURE 23.2

Heart, Lungs, and Legs As you see, most of the elderly do not meet the minimum exercise standards recommended by the Centers for Disease Control—An ageist culture assumes that the patterns of the young are ideal. Consequently, team sports are organized in ways that emerging adults prefer; traditional dancing assumes a balanced sex ratio; many yoga, aerobic, and other classes are paced and designed for people in their 20s. If an old man tries to join a pick-

Added to the problems caused by the ageism of the culture is self-

Especially for Young Adults Should you always speak louder and slower when talking to a senior citizen? (see response, page 674]

Response for Young Adults: No. Some seniors hear well, and they would resent it.

Many people think they are compassionate when they infantilize the elderly, regarding them as if they were children (“so cute,” “second childhood”) (Albert & Freedman, 2010). Some of the elderly accept the stereotype. It is easier not to protest: At every age and for every preconceived idea, changing someone else’s attitudes and assumptions is difficult.

Among the professionals most likely to harbor stereotypes are nurses, doctors, and other care workers. Their ageism is difficult to erase (Eymard & Douglas, 2012), partly because it is based on their experience in treating older patients who are sick and dependent. Understandably, some professionals generalize based on their experiences and treat all elderly as if they were feeble (Williams et al., 2009).

elderspeak A condescending way of speaking to older adults that resembles baby talk, with simple and short sentences, exaggerated emphasis, repetition, and a slower rate and a higher pitch than used in normal speech.

A specific example is elderspeak—the way people talk to the old (Nelson, 2011). Like baby talk, elderspeak uses simple and short sentences, slower talk, higher pitch, louder volume, and frequent repetition. Elderspeak is especially patronizing when people call an older person “honey” or “dear,” or use a nickname instead of a surname (“Billy,” not “Mr. White”).

Ironically, elderspeak reduces communication. Higher frequencies are harder for the elderly to hear, stretching out words makes comprehension worse, shouting causes anxiety, and simplified vocabulary reduces the precision of language.

Destructive Protection

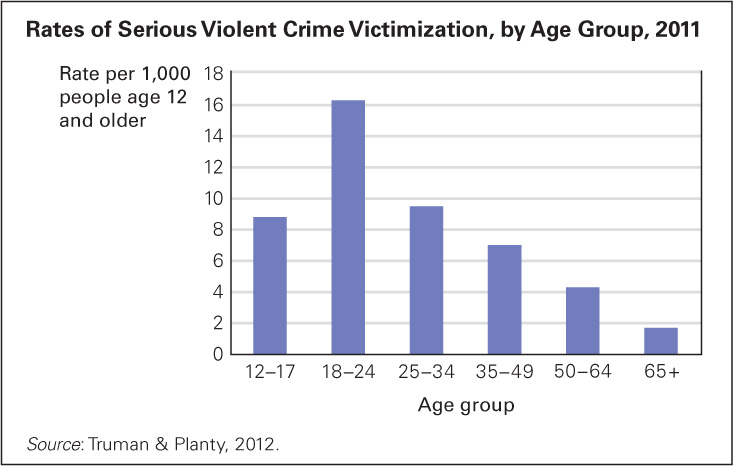

Some younger adults and the media discourage the elderly from leaving home. For example, whenever an older person is robbed, raped, or assaulted, sensational headlines add to fear and consequently promote ageism. In fact, street crime targets young adults, not old ones (see Figure 23.3).

FIGURE 23.3

Victims of Crime As people grow older, they are less likely to be crime victims. These figures come from personal interviews in which respondents were asked whether they had been the victim of a violent crime—The homicide rate (the most reliable indicator of violent crime, since reluctance to report is not an issue) of those over age 65 is less than one-

Although advertisements induce younger adults to buy medic-

In the United States, few elders ride bikes. Protected bike paths are scarce and many bikes are designed for speed, not stability. Laws requiring bike helmets often apply only to children—

The Demographic Shift

demographic shift A shift in the proportions of the populations of various ages.

Demography is the science that describes populations, including population by cohort, age, gender, or region. Demographers describe “the greatest demographic upheaval in human history” (Bloom, 2011, p. 562), a demographic shift in the proportions of the population of various ages. In an earlier era, there were 20 times more children than older people, and only 50 years ago the world had 7 times more people under age 15 than over age 64. This is no longer true.

The World’s Aging Population

The United Nations estimates that nearly 8 percent of the world’s population in 2010 was 65 or older, compared with only 2 percent a century earlier. This number is expected to double by the year 2050. Already 13 percent in the United States are that old, as are 14 percent in Canada and Australia, 20 percent in Italy, and 23 percent in Japan (United Nations, 2012).

As you saw in Chapter 1, demographers often depict the age structure of a population as a series of stacked bars, one bar for each age group, with the bar for the youngest at the bottom and the bar for the oldest at the top (refer to Visualizing Development, p. 680). Historically, the shape was a demographic pyramid. Like a wedding cake, it was widest at the base, and each higher level was narrower than the one beneath it, for three reasons—

- More children were born than the replacement rate of one per adult, so each new generation had more people than the previous one. NOW FALSE

- Many babies died, which made the bottom bar much wider than later ones. NOW FALSE

- Serious illness was almost always fatal, reducing the size of older groups. NOW FALSE

Sometimes unusual events caused a deviation from this wedding-

That fear evaporated as new data emerged. Birth rates fell and a “green revolution” doubled the food supply. Early death has become rare; demographic stacks have become rectangles, not pyramids. Indeed, some people worry about another demographic shift: fewer babies and more elders, which will greatly affect world health and politics (Albert & Freedman, 2010).

This flipped demographic pattern is not yet starkly evident everywhere. Most nations still have more people under age 15 than over age 64. Worldwide, children outnumber elders more than 3 to 1—

MITCHELL KANASHKEVICH/CORBIS

Statistics that Frighten

Unfortunately, demographic data are sometimes reported in ways designed to alarm. For instance, have you heard that people aged 80 and older are the fastest-

In 2010 in the United States there were more than 4 times as many people 80 and older than there were 50 years earlier (11.8 million compared with 2.7 million). The risk of Alzheimer disease increases dramatically with age. Stating the facts that way triggers ageist fears of a nation burdened by hungry hordes of frail and confused elders, requiring billions of dollars of health care in crowded hospitals and nursing homes.

But stop and think. The population has also grown. The percent of U.S. residents age 80 and older has doubled, not quadrupled (increasing between 1960 and 2010 from 1.6 percent to 3.8 percent). That does not overwhelm the other 96.2 percent. What percent of them are in nursing homes or hospitals? (Guess—

dependency ratio A calculation of the number of self-

Statisticians sometimes report the dependency ratio, estimating the proportion of the population that depends on care from others. This ratio is calculated by comparing the number of dependents (defined as those under age 15 or over 64) to the number of people in the middle, aged 15 to 64.

In 2010, the nation with the highest dependency ratio was Uganda, 1:0.98, with more dependents than adults; the lowest was Bahrain, 1:3.5, with one dependent per three and a half adults. In most nations, including the United States, the dependency ratio is about 1:2, that is, one person under 15 or over 64 for two people in between (United Nations, 2012).

But this way of calculating the dependency ratio assumes that older adults are dependent. This mistake is echoed in those dire predictions of what will happen when baby boomers age: supposedly a shrinking number of working adults will carry a crushing burden of senility and fragility. Social Security, Medicare, and public hospitals will be bankrupt, according to some. That specter is alarmist, ageist, and untrue.

The truth is that most elders are fiercely independent. They are more often caregivers, not care receivers, caring not only for each other but also for the young, those other “dependents.”

Only 10 percent of those over age 64 depend on other people for basic care. Those who do need help are more likely to get it from close relatives than tax-

As more and more people reach old age, the proportion (not the number) of elders who are in nursing homes and hospitals is decreasing, not increasing. Most older adults live completely independently, alone or with an aging spouse; a minority are living with adult children, and even fewer are in institutions.

The stereotype is not completely false. It is true that dependency increases after age 80. But it also is true that many very old people remain independent. Compared to most other nations, more people are in long-

Some are admitted to a hospital for a short-

Young, Old, And Oldest

If you guessed that far more than 10 percent of the very old were in nursing homes, do not feel foolish. Almost everyone overestimates because people tend to notice only the feeble, not recognizing the rest. This is a characteristic of human thought—

Other developmental examples of the distortion of the memorable case is thinking of teenagers as delinquents, of single mothers as neglectful, of divorced fathers as deadbeats. When you hear such stereotypes, you probably reject them as ignorant. Hopefully you now recognize that the same distorting tendency feeds ageism.

Gerontologists distinguish among the young-

- The young-

young-

old Healthy, vigorous, financially secure older adults (generally, those aged 65 to 75) who are well integrated into the lives of their families and communities.old are the largest group of older adults. They are healthy, active, financially secure, and independent. Few people notice them or realize their age. - The old-

old-

old Older adults (generally, those over age 75) who suffer from physical, mental, or social deficits.old suffer some losses in body, mind, or social support, but they proudly care for themselves. - Only the oldest-

oldest-

old Elderly adults (generally, those over age 85] who are dependent on others for almost everything, requiring supportive services such as nursing homes and hospital stays.old are dependent, and they are the most noticeable.

Ages are sometimes used to demarcate these three groups. Many of the young-

The reality that most people over age 64 are quite capable of caring for themselves does not mean that they are unaffected by time. The processes of senescence, described in Chapter 20, continue lifelong. Faces wrinkle, bodies shrink, hearing fades. As you remember, such age changes vary a great deal from person to person; good health habits slow down senescence. But aging is ongoing; no 80-

SUMMING UP

Ageism is stereotyping based on age, a prejudice that leads to less competent and less confident elders. Ageism is evident in people of all walks of life and all ages, but it is particularly harmful when it is present in health professionals and in the elderly themselves. Elderspeak is one example.

Demographic changes have resulted in a higher proportion of elders and a lower proportion of children in every nation. In theory, as nations have more elderly people and fewer children, the dependency ratio should stay the same, but this is inaccurate. Basing the dependency ratio on everyone under age 15 and over age 65 is a distortion. Most elders are quite independent and few need full-