Selective Optimization with Compensation

Selective Optimization with Compensation

Ageism distorts reality, but senescence is real. We need to push aside the distortions of ageism and instead look at the actual changes of aging and what can be done about them. As already described in Chapter 20, every part of the body is affected by the passage of time.

How does a person reach old age and still be vital? Several strategies were described in detail in Chapters 17, 20, and 21, specifically: decreasing allostatic load by exercising daily, eating well but not too much, avoiding cigarettes and other drugs, and coping with stress in such a way as to reduce or eliminate stressors. All these are as important in late adulthood as at any other time, perhaps even more so.

Now we highlight another strategy: selective optimization with compensation. The same principles that apply to it apply also to biological vitality. The elderly can compensate for the impairments of senescence and then can perform (optimize) whatever specific tasks they select. [Lifespan Link: Selective optimization with compensation is first described in Chapter 21.]

Every compensatory strategy involves personal choice, societal practices, and technological options. This will be clear with three examples: sexual intercourse, driving, and the senses.

Personal Compensation: Sex

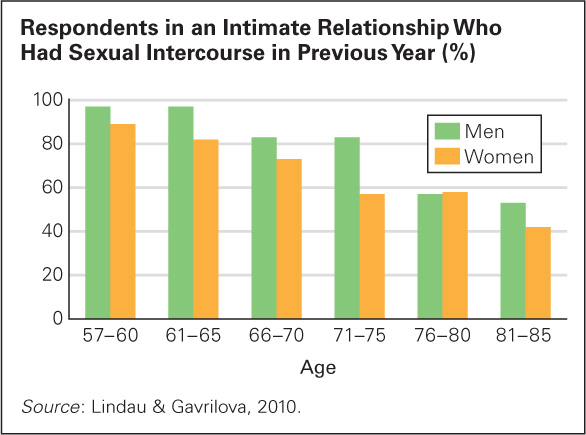

Most people are sexually active throughout adulthood. Some continue to have intercourse long past age 65 (Lindau & Gavrilova, 2010) (see Figure 23.4), but generally intercourse becomes less frequent, and sometimes stops completely. Nonetheless, sexual satisfaction often increases after middle age (Heiman et al., 2011). How can that be?

FIGURE 23.4

Your Reaction Older adults who consider their health good (most of them) were asked if they had had sexual intercourse within the past year. If they answered yes, they were considered sexually active. What is your reaction to the data? Some young adults might be surprised that many adults, aged 60 to 80, still experience sexual intercourse. Other people might be saddened that most healthy adults over age 80 do not. However, neither reaction is appropriate. For many elders, sexual affection is expressed in many ways, and it continues lifelong.Many older adults reject the idea that intercourse is the only, or best, measure of sexual experience. Instead, cuddling, kissing, caressing, desiring, and fantasizing become more important (Chao et al., 2011). A five-

The following in-

CATHRINE STUKHARD/LAIF/REDUX

A CASE TO STUDY

Should Older Couples Have More Sex?

Usually, case studies are of one or two individuals and seek to provide suggestions to be researched through surveys and experiments with hundreds of participants. [Lifespan Link: The major methods of scientific research are discussed in Chapter 1.] However, research on sex may be an exception. A laboratory experiment on intimate sex between two lovers, or a survey about sex worded so that everyone would give accurate answers, is difficult to design and undertake.

Two researchers wanted to study sexual activity among the elderly, but they feared that laboratory measures of sexual arousal might be calibrated on young bodies and that questions about sex might be misinterpreted by the elderly (Lodge & Umberson, 2012).

Accordingly, they used a method called grounded theory. They found 17 couples, aged 50 to 86, most married for decades, and interviewed each person privately, transcribing all 34 interviews. Next they read and reread all the transcripts, identifying topics that came up repeatedly. Then they tallied those topics in the transcripts, line by line, sorted by age and gender, to learn about aging sexual relationships.

From their study they concluded that sexual activity was more a social construction than a biological event (Lodge & Umberson, 2012). They reported that everyone said that sex was less frequent with age, including four couples for whom intercourse stopped completely because of the husband’s health. Despite sex being less frequent, more of the respondents said that their sex life had improved than said it deteriorated (44 percent compared to 30 percent).

Surprisingly, the middle-

The middle-

One woman said:

All of a sudden, we didn’t have sex after I got skinny. And I couldn’t figure that out. I look really good now and we’re not having sex. It turns out that he was going through a major physical thing at that point and just had lost his sex drive. It didn’t have anything to do with me, but I thought it did. I went through years thinking it was my fault. So, let’s go make sure it’s your fault (laughs) or let’s find out what the problem is instead of me just assuming the blame.

[Irene, quoted in Lodge & Umberson, 2012, p. 435]

The authors believe that “images of masculine sexuality are premised on high, almost uncontrollable levels of penis-

A few years later, as couples grew older (over age 70), the study showed they realized that the young idea of good sex (which many still thought of as intercourse) was not relevant. Instead they compensated for physical changes by optimizing their relationship in other ways. As one man said:

I think the intimacy is a lot stronger even though the sex is bad. Probably more often now we do things like holding hands and wanting to be close to each other or touch each other. It’s probably more important now than sex is.

[Jim, quoted in Lodge & Umberson, 2012, p. 438]

A woman said her marriage improved because

[w]e have more opportunities and more motivation. Sex was wonderful. It got thwarted, with … the medication he is on. And he hasn’t been functional since. The doctors just said that it is going to be this way, so we have learned to accept that. But we have also learned long before that there are more ways than one to share your love.

[Helen, quoted in Lodge & Umberson, 2012, p. 437]

The authors point out that their findings may not be true for all couples in the future. This cohort grew up with the social construction that men were rapacious and women had to be restrained but attractive. Both sexes were taught when they were young that sexual desire stopped before old age. It was considered deviant (dirty old man) or ridiculous (why is she wearing that tight skirt?) if an older adult still felt sexy.

Then this cohort witnessed the sexual revolution. Sex was suddenly accepted: Unmarried adults and old people were now considered happier and healthier if they had active sex lives. Although nursing homes and assisted living quarters had been constructed to make intercourse rare or impossible, social scientists suggested that they be redesigned to encourage sex (Frankowski & Clark, 2009). No wonder these middle-

The next cohort of older adults may have other attitudes; the male/female and midlife/older differences evident with these 17 couples may not apply. These cases do suggest, however, that preconceptions about sex and older adults may be mistaken.

Married couples adjust to whatever biological changes occur in their sexual arousal, but many also improve their relationship in the process (Lodge & Umberson, 2012). This is an example of selective optimization with compensation. A similar process occurs for individuals after divorce or death of a partner. Since the sex drive varies from person to person, some single elders consider sex a thing of the past, some cohabit, some begin LAT (living apart together) with a new partner, and some remarry. That is selective optimization—

Neither the old myth, that no normal older person wants sex, nor the new myth, that all older people have strong sexual desires, is accepted by elderly people themselves. Of course, with every social construction, society makes some options difficult, which leads to the next topic.

Social Compensation: Driving

A life-

How Individuals Respond

With age, reading road signs takes longer, turning the head becomes harder, reaction time slows, and night vision worsens. The elderly compensate: Many drive slowly and reduce driving in the dark.

Relying on individuals to decide when and whether to stop driving is foolhardy, however. In the United States, driving one’s car is a source of independence, so the elderly are understandably reluctant to quit. In addition, some critics are ageist, not accurate (Satariano et al, 2012). Consequently, many old people who have driven all their lives insist they are still good drivers and resent age-

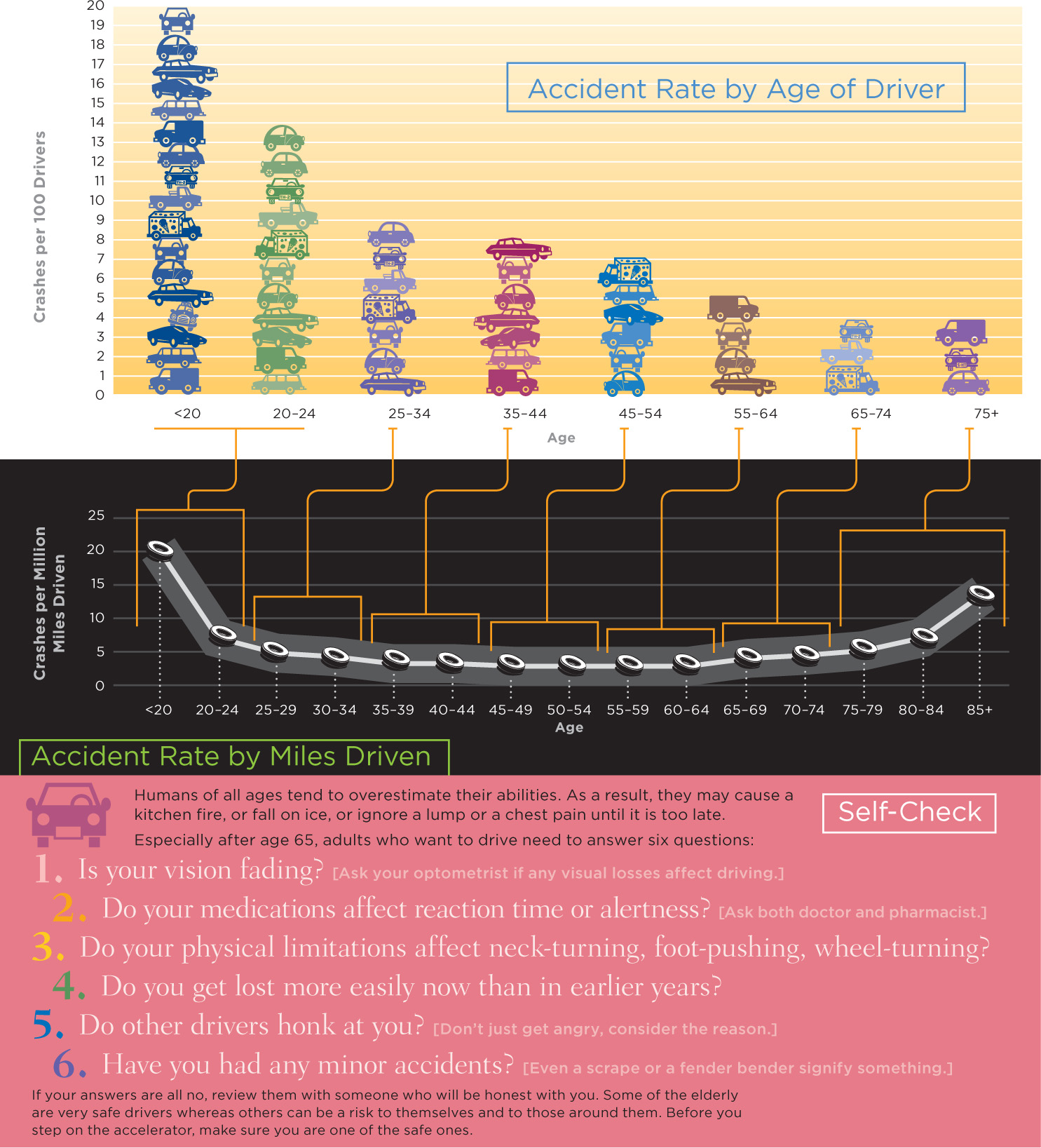

Because they are cautious and limit themselves, elderly drivers have fewer accidents than 20-

Although older drivers try to compensate, many do not realize how significant their losses are. For instance, one common problem is a reduced ability to estimate speed of oncoming cars. Without that, it is difficult to safely merge into highway traffic. How can an older adult know that speed estimation is reduced? Must that knowledge wait until a near or real collision?

What Jurisdictions Can Do

Societies need to compensate for age-

If testing is required before license renewal, it often focuses on answering multiple-

Technology has now come up with a way to solve this problem. A national panel recommends simulated driving via a computer and video screen, with the prospective driver seated with a steering wheel, accelerator, and brakes (Sifrit, 2012). The results of this test could allow some 80-

Beyond retesting, there is much else that societies can do. Larger-

Another society-

VISUALIZING DEVELOPMENT

Social Comparison: Elders Behind the Wheel

Older people often change their driving habits in order to compensate for their slowing reaction time. Many states have initiated restrictions, including requiring older drivers to renew their licenses in person, to make sure older drivers stay safe. Because most older drivers limit themselves (they avoid night, rainy, and distance driving), their crash rate is low overall, but not when measured by the rate per miles driven.

Technological Compensation: The Senses

Every sense becomes slower and less sharp with each passing decade. This is true for touch (particularly in fingers and toes), pain, taste (particularly for sour and bitter), smell, as well as for sight and hearing. Hundreds of manufactured devices compensate for sensory loss, from eyeglasses (first invented in the thirteenth century) to tiny video cameras worn on the forehead that connect directly to the brain, allowing people who are blind to process images (not yet commercially available).

Vision

Only 10 percent of people of either sex over age 65 see well without glasses (see Table 23.1), but selective optimization allows almost everyone to use their remaining sight quite well. Changing the environment—

|

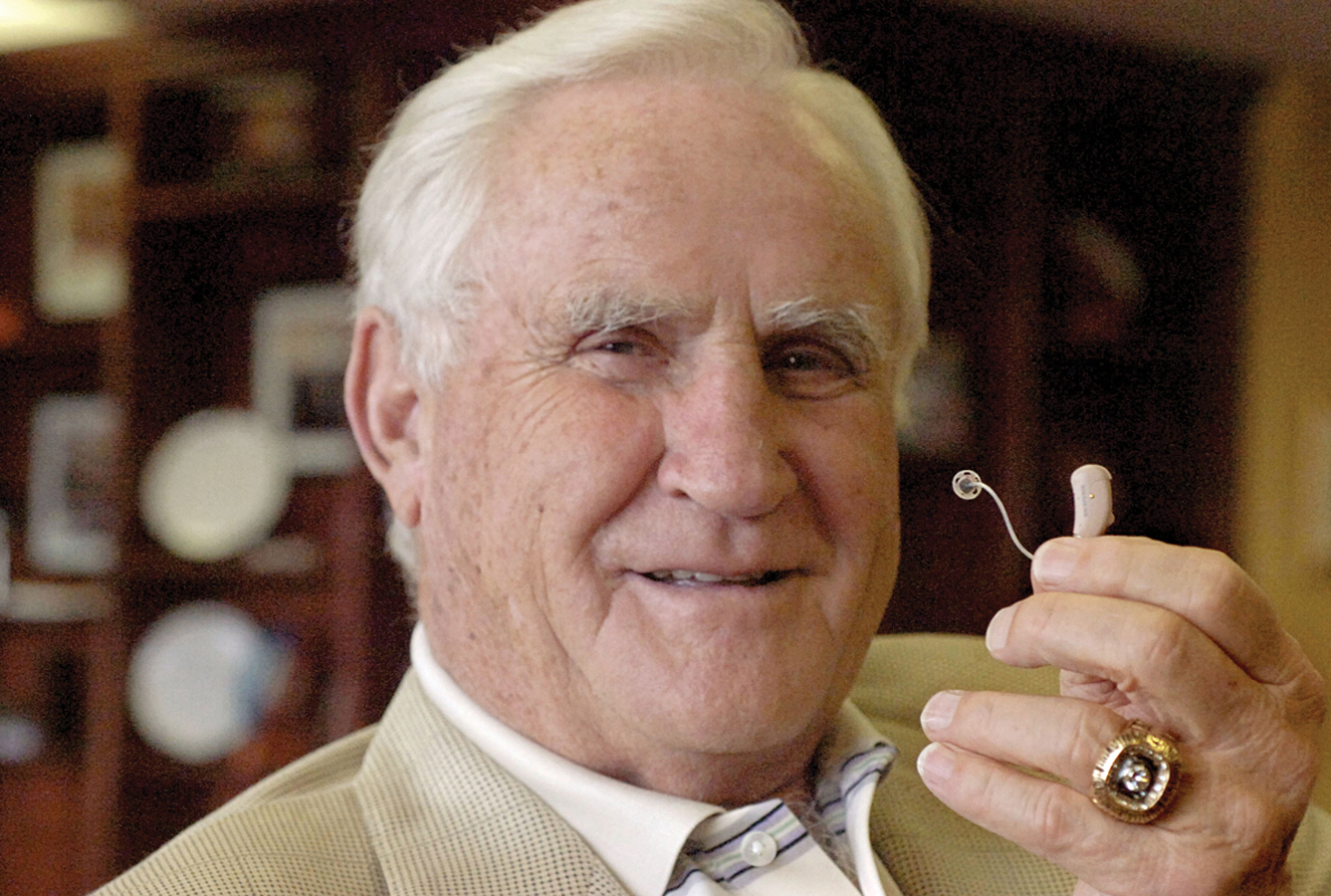

Hearing

By age 90 the average man is almost deaf, as are about half the women. That may be an overestimate. Since deafness is a matter of degree, it is hard to know where to draw the line. The Gallaudet Research Institute puts hearing difficulties at 29 percent over age 65; a scholar who examined U.S. Census records suggests about half that, 16 percent (Mitchell, 2006).

Everyone agrees, however, that hearing impairment increases dramatically with age and that deafness is far more common in men than in women. For all sensory deficits, an active effort to compensate—

Ageism affects whether a society provides technological help. A dramatic improvement in the ability of deaf people to enjoy concerts, plays, museums, and so on results from a “hearing loop,” a small device in a room that enables people with hearing aids to hear the words or music they want, without the distracting clatter. Installing a loop requires someone to realize that it is worth the cost. David Myers, himself now hearing impaired, explains:

The Americans with Disabilities Act does, however, mandate hearing assistance in public settings with 50 or more fixed seats. Such assistance typically takes the form of a checkout FM or infrared receiver with earphones. Alas, because well-

To empathize, imagine yourself struggling to carve meaning out of sound as you watch a movie, attend worship, listen to a lecture, strain to hear an airport announcement, or stand at a ticket window. Which of these hearing solutions would you prefer?

- Taking the initiative to locate, check out, wear, and return special equipment (typically a conspicuous headset that delivers generic sound)?

- Pushing a button that transforms your hearing aid (or cochlear implant) into wireless loudspeakers that deliver sound customized to your own needs?

Solution 1—

[Myers, 2011, pp. 1-

universal design The creation of settings and equipment that can be used by everyone, whether or not they are able-

Disability advocates hope more designers and engineers will think of universal design, which is the creation of settings and equipment that can be used by everyone, whether or not able-

Look around at the “built” environment (stores, streets, colleges, and homes); notice the print on medicine bottles; listen to the public address systems in train stations; ask why most homes have entry stairs and narrow bathrooms, why most buses and cars require a big step up to enter, why smelling remains the usual way to detect a gas leak. Then look for signs that indicate accessibility or hearing loop availability, and find out how accurate those signs are. Too often elevators are not in service, curb cuts are not smooth, ramps are hidden, and so on.

Sensory loss need not lead to morbidity or cognitive loss, but without compensation, any disability, including deafness and blindness, can lead to isolation, less movement, and reduced intellectual stimulation. Often illness increases and cognition declines as the senses fade.

Compensation for the Brain

For the three topics just mentioned in relation to physiological problems of aging—

Thus, a person must decide that sexual touch is as rewarding as intercourse. Sexual arousal begins in the brain, not the genitals, which is why a dream, a photograph, or a voice on the phone can trigger arousal and why ageism can reduce desire.

Likewise, people must realize that their senses are fading, must decide to use technology, must find the appropriate device, and then must learn to use it. Many hearing aids stay in boxes beside the bed because the person does not know how to make them work properly.

The United States Department of Transportation has analyzed crash risk among the elderly and found that the biggest risk is in cognition, not in vision or motor skills (Sifrit, 2012). To forget which pedal is the brake is far worse than the loss of some foot strength, which might prevent an older person from pushing the brake as hard as a younger driver. The most common reason for a fatal crash with an elderly driver is that the driver turned left at an intersection into oncoming traffic—

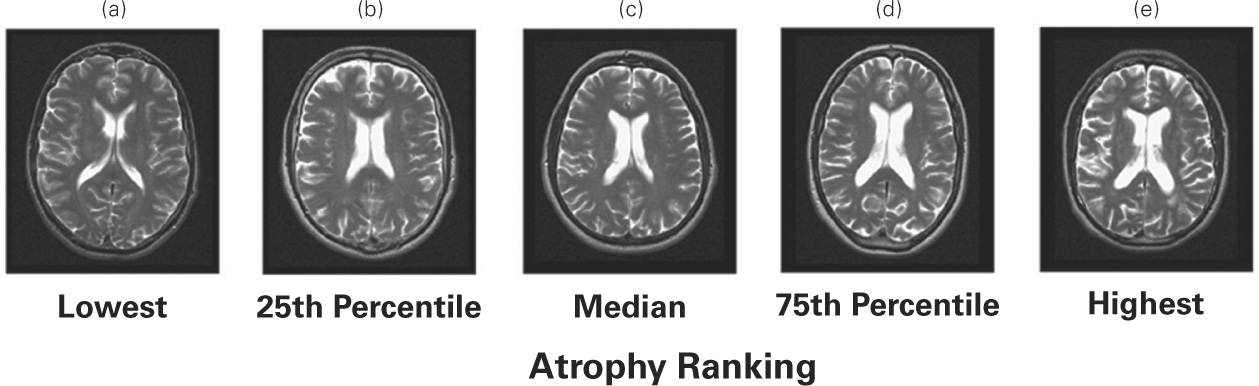

What then happens to the brain as humans age? It slows down, and connections between parts weaken, so people take longer to understand what is needed in a particular situation. Comprehension becomes more difficult because the white and gray matter of the brain are reduced. For instance, reading rate slows and conversation partners need to talk more slowly.

The volume of the brain decreases with each passing year—

More detailed research finds that brain shrinkage is most evident in particular regions: more in the neocortex than in more primitive parts of the brain, and especially notable in the hippocampus, the part of the brain that stores memories, and the prefrontal cortex, where decision making and planning occur. New neurons form as well, and cognitive reserve allows some brains to function well even when aging has continued for years. However, neither of these processes completely compensates for brain senescence (Stern, 2013).

Brain shrinkage and cell loss are particularly notable among the oldest-

The brain is critical for all compensatory mechanisms just described. A person must think before any optimization occurs. Perhaps the brain is the organ that most needs the personal, social, or technological assistance described above.

The crucial question is: Can anything be done to compensate for brain losses in old age, to optimize thinking as people can optimize sex, or driving ability, or sensory acuteness? The answer is yes, sometimes. Brain plasticity is possible throughout life (e.g., Ram et al., 2011; Erickson et al., 2013). The same factors that protect the rest of the body protect the brain, especially exercise, nutrition, and avoiding drugs (including cigarettes). Beyond that, many specifics about memory and cognition affect late-

SUMMING UP

Selective optimization with compensation applies to every aspect of senescence. Older adults do not have the same sexual activity, driving ability, or sensory acuteness as younger adults. In every case, however, measures can counteract these deficits if they are recognized and understood. Some of those measures come from the awareness of the individuals themselves. For instance, many older couples enjoy their sexual interaction, even though it is not what it was when they were younger. Other compensation comes from technology, if individuals and societies choose to use it. Driver license tests are one example: Few jurisdictions currently test the elderly for the skills that are known to be crucial for avoiding accidents. Most sensory losses can be prevented or ameliorated, but many of the elderly do not get medical treatment or use the aids that are available. The master organ that can orchestrate all the necessary adjustments is the brain, which itself shrinks and slows with age.