The Aging Brain

The Aging Brain

Ageism impairs elders in many ways, but the most feared and insidious impairment involves the mind, not the body. As with many stereotypes, the notion of cognitive decline in late adulthood begins with a half-

New Brain Cells

Especially for People Who Are Proud of Their Intellect What can you do to keep your mind sharp all your life?

Response for People Who Are Proud of Their Intellect: If you answered, “Use it or lose it” or “Do crossword puzzles,” you need to read more carefully. No specific brain activity has proved to prevent brain slowdown. Overall health is good for the brain as well as for the body, so exercise, a balanced diet, and well-

The most exciting news regarding brain development in later life is that neurons form and dendrites grow in adulthood. That surprised many scientists when it was first discovered. Almost everyone thought that humans developed no new brain cells after infancy.

We now know that neurons develop in the adult brain particularly in two specific areas, the olfactory region (smelling) and the hippocampus (remembering).

Some antidepressants create new neurons that repair damage to the hippocampus caused by earlier stress hormones (Serget et al., 2011). In addition, old neurons can develop new dendrites, allowing adults to shake the grip of depression and anxiety (Mateus-

Although neurogenesis may occur in many living things, an evolutionary perspective suggests that the generation of new neurons in humans may occur for unique reasons (Kempermann, 2012). When agriculture began (widely believed to be approximately 10,000 years ago), adult life started to require more planning, remembering, and strategizing than was previously necessary. People faced more complexities in nourishing the population than was the case with the nomadic hunting and gathering that earlier humans did and that wild animals still do. Further, the brain adjusted as humans faced the new challenges of gathering in towns, which meant they had to interact with much larger social groups.

The idea that the complex social interactions of human life led to new brain development is an attractive one. As one scholar suggests, “moving actively in a changing world and dealing with novelty and complexity regulate adult neurogenesis. New neurons might thus provide the cognitive adaptability to conquer ecological niches rich with challenging stimuli” (Kempermann, 2012, p. 727).

As you remember from Chapter 21, in the twentieth century the evidence suggests that the intellectual ability of each new cohort is better than that of the previous one. Perhaps the increasing complexity of modern life requires continuing improvement, with urbanization and globalization demanding intellectual expansion. Thus older people who continue to cope with challenges will continue to grow neurons.

The positive finding that neurons are created is tempered by a more negative fact—

Senescence and the Brain

The cold fact that senescence affects the brain has been known for decades. Recent research has brought the good news that new brain cells and dendrites can develop, but the old news is still true—

Slower Thinking

Senescence reduces the production of neurotransmitters—

This slowdown can prove a severe drain on the intellect because speed is crucial for many aspects of cognition. In fact, some experts believe that processing speed is the g mentioned in Chapter 21—

Deterioration of cognition correlates with slower movement as well as with almost every kind of physical disability (Kuo et al., 2007; Salthouse, 2010). For example, gait speed correlates strongly with many measures of intellect (Hausdorff & Buchman, 2013). Walks slow? Talks slow? Oh no—

Smaller Brains

Brain aging is evident not only in processing speed but also in size, as the total volume of the brain becomes smaller. Shrinkage is particularly notable in the hippocampus and the areas of the prefrontal cortex that are needed for planning, inhibiting unwanted responses, and coordinating thoughts (Rodrigue & Kennedy, 2011).

In every part of the brain, the volume of gray matter (crucial for processing new experiences) is reduced, in part because the cortex becomes thinner with every decade of adulthood (Zhou et al., 2013). As a consequence, many people must use their cognitive reserve (Park & Reuter-

These white matter lesions are thought to result from tiny impairments in blood flow. They increase the time it takes for a thought to be processed in the brain (Rodrigue & Kennedy, 2011). Slowed transmission from one neuron to another is not the only problem. With age, transmission of impulses from entire regions of the brain, specifically from parts of the cortex and the cerebellum, is disrupted. Specifics correlate more with cognitive ability than with age (Bernard et al., 2013).

Variation in Brain Efficiency

As with every other organ, all the aspects of brain senescence vary markedly from individual to individual, in part because of the individual’s health and habits. Higher education and vocational status correlate with less cognitive decline. There are three plausible hypotheses for the connection between high SES and high intellect:

- High-

SES people began late adulthood with more robust and flexible minds, so their losses are not as noticeable. - Keeping the mind active is protective.

- High-

SES people generally avoid pollution and drugs, and have better medical care than low- SES people.

The first hypothesis seems to have the greatest amount of research support. The intellectually gifted may lose cognitive speed at the same rate as other people, but they began late adulthood as such quick thinkers that the slowdown is less apparent (Puccioni & Vallesi, 2012). But the second hypothesis also has support: The intellectually gifted are more open to new ideas, and that openness produces a more active mind (Hogan et al., 2012). This is the “use it or lose it” hypothesis, an attractive idea that has many of the elderly doing crossword puzzles and Sudoku, but not one that researchers have proven.

Finally, no one doubts that health is crucial. Exercise, nutrition, and normal blood pressure are powerful influences on brain health, and these factors predict intelligence in old age. Some experts contend that with good health habits and favorable genes, no intellectual decrement will occur (Greenwood & Parasuraman, 2012).

Variation is also evident in which parts of the brain shut down first. Names are forgotten faster than faces, spatial representation (where did I put that?) faster than vocabulary (what is that called?). This variation may be strictly biological (hypothesis one) or a matter of practice (hypothesis two). No doubt it is affected by blood circulation in the brain (hypothesis three).

Using More of the Brain

A curious finding from PET and fMRI scans is that, compared with younger adults, older adults use more parts of their brains, including both hemispheres, to solve problems. This may be compensation: Using only one brain region may no longer be sufficient if that part has shrunk, so the older brain automatically activates more parts.

Consequently, older adults are as intellectually sharp as they always were on many tasks. However, in performing difficult tasks that require younger adults to use all their cognitive resources, older adults are less proficient, perhaps because they already are using their brains to the max (Cappell et al., 2010).

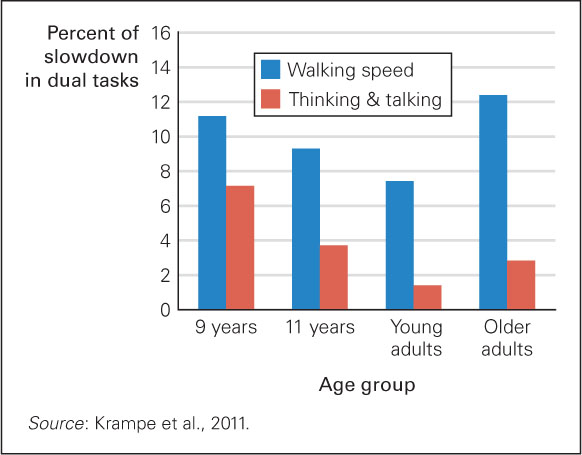

Brain shrinkage interferes with multitasking even more than with other cognitive challenges. No one is intellectually as efficient with two tasks as with one, but young children and old adults are particularly impaired by doing several tasks (Krampe et al., 2011) (see Figure 24.1). Recognizing this fact, many elders are selective; they sequence tasks rather than try to do two things at once.

Observation Quiz In Figure 24.1, how much were the 9-

Answer to Observation Quiz: Nine-

FIGURE 24.1

One Task at a Time Doing two things at once impairs performance. In this study, researchers compared the speed of a sensorimotor task (walking) and a cognitive task (naming objects within a category—Suppose that a man is interrupted by his grandchild’s questions while reading the newspaper, or that grandchild asks grandma which bus to take while she is getting dressed. A wise man puts down the newspaper and then answers, and grandmother will first dress and then think about transportation (avoiding mismatched shoes).

SUMMING UP

The human brain is constantly changing and developing as long as a person is alive, even adding new cells and growing new dendrites. However, like every other body part, the brain shows signs of age. It becomes smaller overall. Some parts are particularly likely to shrink, especially gray matter, the prefrontal cortex, and the hippocampus. Neurotransmitters, myelination, and white matter are also reduced, with new, intense white spots. The result of all these changes is that the transmission of messages from one neuron to another slows, which is evident in how fast people move their bodies (such as walking) and how quickly they remember a name.

Remarkable plasticity is also apparent, with wide variation in the rate and specifics of brain slowdown. In general, older adults use more of their brains, not less, to do various tasks, and they prefer doing one task at a time, avoiding multitasking.