Information Processing After Age 65

Information Processing After Age 65

Given the complexity, variation, and diversity of late-

Input

The first step in information processing is input, in which the brain receives information from the senses, but, as Chapters 20 and 23 explain, no sense is as sharp at age 65 as at age 15. Glasses and hearing aids mitigate severe sensory losses, but more subtle deficits impair cognition as well. In order to be perceived, information must cross the sensory threshold—the divide between what is sensed and what is not. [Lifespan Link: Sensory memory is explained in Chapter 12.]

A person may not recognize sensory losses because the brain automatically fills in missed sights and sounds. People of all ages believe they look at the eyes of their conversation partner, yet a study that examined the ability to follow a gaze found that older adults were less adept at knowing where someone was looking (Slessor et al., 2008). That creates a disadvantage in social interactions. Another study found that already by age 50, adults were less adept at reading emotions by looking at the eyes (Pardini & Nichelli, 2009).

Acute hearing is another way to detect emotional nuances. Older adults are less able to decipher the emotional content in speech, even when they hear the words correctly (Dupuis & Pichora-

I know a father—

The cognition of almost 2,000 intellectually normal older adults, average age 77, was repeatedly tested 5, 8, 10, and 11 years after the initial intake (Lin et al., 2013). At the 5-

That 2 percent difference seems small, but statistically it was highly significant (.004). Furthermore, greater hearing losses correlated with greater cognitive declines (Lin et al., 2013). Many other researchers likewise find that small input losses have a notable effect on output.

Memory

After input, the second step is processing whatever input has come from the senses. Stereotype threat impedes this processing. [Lifespan Link: Stereotype threat was discussed in Chapter 18.] If older people suspect memory loss, anxiety itself impairs their memory (Ossher et al., 2013). Worse than that, simply knowing that they are taking a memory test makes them feel years older (Hughes et al., 2013). As you learned in Chapter 23, feeling old itself impairs health.

The more psychologists study memory, the more they realize that memory is not one function but many, each with a specific pattern of loss. Some losses of the elderly are quite normal and others pathological (Markowitsch & Staniloiu, 2012). The inability to recall a word or a name is a normal loss of one aspect of memory, and does not indicate that memory, overall, is fading.

Especially for Students If you want to remember something you learn in class for the rest of your life, what should you do?

Response for Students: Learn it very well now, and you will probably remember it in 50 years, with a little review.

Generally, explicit memory (recall of learned material) shows more loss than implicit memory (recognition and habits). That means that names are harder to remember than actions. Grandpa can still swim, ride a bike, and drive a car, even if he cannot name both U.S. senators from his state.

One memory deficit is source amnesia—forgetting the origin of a fact, idea, or snippet of conversation. Source amnesia is particularly problematic in the twenty-

In practical terms, source amnesia means that elders might believe a rumor or political advertisement because they forget the source. Compensation requires deliberate attention to the reason behind a message before accepting a con artist’s promises or the politics of a TV ad. However, elders are less likely than younger adults to analyze, or even notice, information surrounding the material they remember (Boywitt et al., 2012).

Another crucial type of memory is called prospective memory—remembering to do something in the future (to take a pill, to meet someone for lunch, to buy milk). Prospective memory also fades notably with age (Kliegel et al., 2008). This loss becomes dangerous if, for instance, a person cooking dinner forgets to turn off the stove, or if someone is driving on the thruway in the far lane when the exit appears.

The crucial aspect of prospective memory seems to be the ability to shift the mind quickly from one task to another: Older adults get immersed in one thought and have trouble changing gears (Schnitzspahn et al., 2013). For that reason, many elders follow routine sequences (brush teeth, take medicine, get the paper) and set an alarm to remind them to leave for a doctor’s appointment. That is compensation.

Working memory (remembering information for a moment before evaluating, calculating, and inferring its significance) also declines with age. Speed is critical: Some older individuals take longer to perceive and process sensations, which reduces working memory because some items fade before they can be considered (Stawski et al., 2013).

For example, a common test of working memory is to have someone repeat backwards a string of digits just heard, but if the digits are said quickly, a slow-

Some research finds that when older people have adequate time, working memory does not fade. Speed is crucial when comparing working memory between one older adult and another, but paying attention becomes the critical factor when a person is tested repeatedly over several days (Stawski et al., 2013).

Thus adequate time and careful attention are both crucial. This explains interesting results from a study of reading ability. In that research, older people reread phrases more often than younger people did, but when both groups had ample time to pay attention, comprehension was not impaired by age (Stine-

Control Processes

The next step in information processing involves control processes (discussed in Chapter 12). Many scholars believe that the underlying impairment of cognition in late adulthood is in this step, as information from all parts of the brain is analyzed by the prefrontal cortex. Control processes include selective attention, strategic judgment, and then appropriate action—

Instead of using analysis and forethought, the elderly tend to rely on prior knowledge, general principles, familiarity, and rules of thumb as they make decisions (Peters et al., 2011), basing actions on past experiences and current emotions.

For example, casinos have noticed that elderly gamblers gravitate to slot machines rather than to games where analysis is helpful. The reason, according to a study of brain scans of young and old slot players, is that the activated parts of older brains are less often the regions in which analysis occurs (McCarrey et al., 2012). When gamblers are able to analyze the odds, as younger players do, they spend less time with slots.

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

Cool Thoughts and Hot Hands

As you remember from the discussion of dual processing in Chapter 15, experiential, emotional thinking is not always faulty, but sometimes analytic thinking is needed to control impulsive, thoughtless reactions.

This was apparent in a study of belief in the “hot hand,” which is the idea that athletes are more likely to score if they scored in the immediately previous attempts. One study found that most people (91 percent) believe that players can be “on a roll” or that teams can have “a winning streak” (Gilovitch et al., 1985).

Most people are wrong about this; the hot hand is an illusion. Of course, the best players are more likely to score than the worst ones, but statistical analysis from basketball, golf, and other sports finds that one successful shot does not affect the chance that a particular player will make the next one.

People want to believe in streaks, so they forget when streaks do not occur. This misperception has become a classic example of the human tendency to ignore data that conflicts with assumptions (Kahneman, 2011).

Do people become more or less likely to follow their preconceptions rather than using logic to consider new information as they age? In one study, 455 people aged 22 to 90 were told that, overall, about half the time basketball shots miss. That was supposed to remind them to think analytically, not emotionally. Then they were asked two questions:

Does a basketball player have a better chance of making a shot after having just made the last two or three shots than after missing the last two or three shots?

Is it important to pass the ball to someone who has just made several shots in a row?

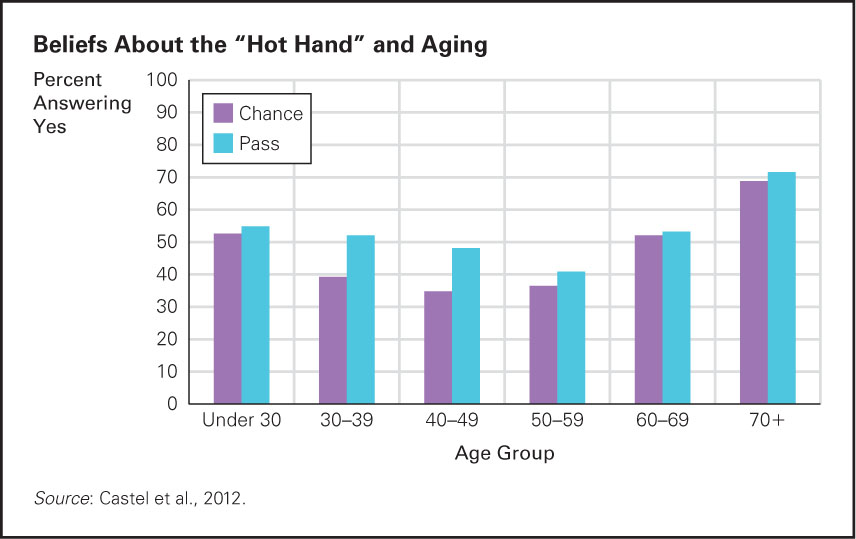

The correct answer to both questions is No, but in this study, elders were particularly likely to say Yes, sticking to their hot hand belief (Castel et al., 2012) (see Figure 24.2).

FIGURE 24.2

Hard to Chill This shows the percent of adults who answered “Yes” to the two questions, which meant that they were not thinking analytically. As you see, the oldest participants were most likely to stick to their “hot hand” prejudice. However, also notice that about one-One particular control process is development of strategies for retrieval. Some developmentalists believe that impaired retrieval is an underlying cause of intellectual lapses in old age because elders have many thoughts and memories that they cannot access. Since deep thinking requires recognizing and comparing the similarities and differences in various experiences, if a person cannot retrieve memories of the past, new thinking is more shallow than it might otherwise be.

Inadequate control processes may explain why many older adults have extensive vocabularies (measured by written tests) but limited fluency (when they write or talk), why they are much better at recognition than recall, why tip-

Many gerontologists think elders would benefit by learning better control strategies. Unfortunately, even though “a high sense of control is associated with being happy, healthy, and wise,” many older adults resist suggested strategies because they believe that declines are “inevitable or irreversible” and that no strategy can help (Lachman et al., 2009, p. 144). Efforts to improve their use of control strategies are often discouraging (McDaniel & Bugg, 2012).

Output

The final step in information processing is output. In daily life, output is usually verbal. If the timbre and speed of a person’s speech sounds old, ageism might cause listeners to dismiss the content without realizing that the substance may be profound. Then, if elders realize that what they say is ignored, they talk less. Output is diminished. This provides guidance for anyone who wants to respect and learn from someone else: We all talk more if we think someone is listening appreciatively.

Scientists usually measure output through use of standardized tests of mental ability. As already noted, if older adults think their memory is being tested, that alone impairs them (Hughes et al., 2013). Even without stereotype threat, output on cognitive tests may not reflect ability, as you will now see.

Cognitive Tests

In the Seattle Longitudinal Study (described in Chapter 21), the measured output of all five primary mental abilities—

Similar results are found in many tests of cognition: Thus, the usual path of cognition in late adulthood as measured by psychological tests is gradual decline, at least in output (Salthouse, 2010). However, such tests are normed and validated via the output of younger adults. To avoid cultural bias, many questions are quite abstract and timed, since speed of thinking correlates with intelligence for younger adults. A smart person is said to be a “quick” thinker, the opposite of someone who is “slow.”

But abstract thinking and processing speed are the aspects of cognition that fade most with age. Is there a better way to measure output in late adulthood?

Ecological Validity

ecological validity The idea that cognition should be measured in settings and conditions that are as realistic as possible and that the abilities measured should be those needed in real life.

Perhaps ability should be measured in everyday tasks and circumstances, not as laboratory tests assess it. To do measurements in everyday settings is to seek ecological validity, which may be particularly important when measuring cognition in the elderly (Marsiske & Margrett, 2006).

For example, because of changes in their circadian rhythm, older adults are at their best in the early morning, when adolescents are half asleep. If a study were to compare 85-

Similarly, if intellectual ability were to be assessed via a timed test, then faster thinkers (usually young) would score higher than slower thinkers (usually old), even if the slower ones would be more accurate with a few more seconds to think. Furthermore, contextual effects might cause anxiety, for instance, if the test occurred in a college laboratory.

Indeed, age differences in prospective memory are readily apparent in laboratory tests but disappear in some naturalistic settings, a phenomenon called the “prospective memory-

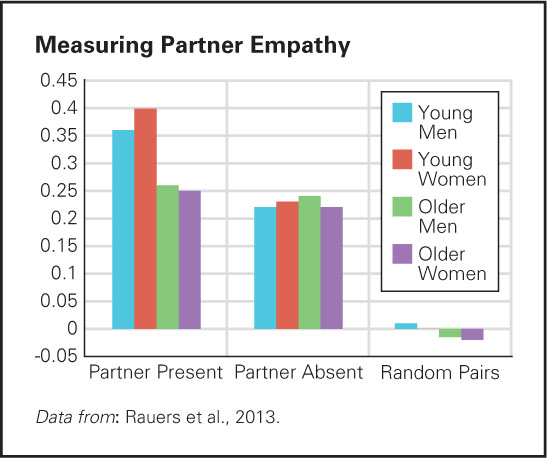

Similarly, as already noted, older adults are not as accurate as younger adults when tested on the ability to read emotions by looking at someone’s face or listening to someone’s voice. But seeing and hearing are less acute with age, so they may not be the best way to measure empathy in older adults. Accordingly, a team decided to measure empathy when visual contact was impossible.

FIGURE 24.3

Always on My Mind When they were together, younger partners were more accurate than older ones at knowing their partner’s emotions, but older partners were as good as younger ones when they were apart. This study used “smart phone experience sampling,” buzzing both partners simultaneously to ask how they and their partner felt. Interestingly, differences were found with age but not length of relationship—Their study included a hundred couples who had been together for years, and each of the participants was repeatedly asked to indicate their own emotions (how happy, enthusiastic, balanced, content, angry, downcast, disappointed, nervous they were) and to guess the emotions of their partner at that moment. Technology helped with this: The participants were beeped at various times, and indicated their answers on a smart phone they kept with them. Sometimes they happened to be with their partner, sometimes not.

When the partner was present, accuracy was higher for the younger couples, presumably because they could see and hear their mate. But when the partner was absent, the older participants were as good as the younger ones (see Figure 24.3). Could you

predict a social partner’s feelings when that person is absent? Your judgment would probably be better than chance, and although many abilities deteriorate with aging, this particular ability may remain reliable throughout your life.

[Rauers et al., 2013, p. 2215]

The fundamental ecological issue for developmentalists is what should be assessed—

Awareness of the need for ecological validity has helped scientists restructure research on memory. Restructured studies find fewer deficits than originally thought. However, any test may overestimate or underestimate ability. For instance, what is an accurate test of long-

Unfortunately, “there is no objective way to evaluate the degree of ecological validity … because ecological validity is a subjective concept” (Salthouse, 2010, p. 77). It is impossible to be totally objective in assessing memory; memory is always subjective.

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

How to Measure Output

Finding the best way to measure cognition is particularly important if a decision is to be made as to whether an older person is able to live independently. An increasing number of the elderly live alone. Is this safe? Might they forget to turn off the stove, or ignore symptoms of a heart attack, or fall prey to a stranger who wants them to invest their money in a harebrained scheme? Many people seek to protect the elderly from failing cognition while allowing as much independence as possible.

Recently, tests have been developed to measure practical problem solving (Law et al., 2012). Some involve short-

Scores on such tests show less discrepancy between the old and the young than scores on abstract memory tests. Perhaps only when an older person living alone fails practical tests is it time for intervention.

Unfortunately, even tests that attempt to be ecologically valid may be inaccurate (Law et al., 2012). Perhaps the best way to test cognitive ability is to be quite direct, asking questions about missed appointments, lost keys, and so on of a person or of someone who knows them well. Yet even direct questions may not be answered accurately, in part because many of the elderly do not want to admit memory loss. Added to that, many family members and professionals, themselves growing older, do not want to admit to their memory loss—

Which of these three measures is best? A study that compared self-

In that study, the self-

Inaccurate self-

By contrast, some people in this study reported many memory problems: They typically did better on the formal tests than their self-

But wait. Consider an opposing perspective. Is the gap between self-

We know that stereotypes are insidious, that global assessments are over-

The final ecological question is, “What is memory for? “Older adults usually think they remember well enough. Fear of memory loss is more typical at age 60 than at age 80. Unless they develop a brain condition such as Alzheimer disease (soon described), elders are correct: They remember how to live their daily lives. Is that enough?

SUMMING UP

Every step in information processing is affected by age. As the senses become less acute, people miss some input. Some stimuli never arrive in the brain, and thus cannot inform thought. Memory also is slower, especially memory for names and places. However, some memories seem intact, including memory for words, emotions, and automatic (implicit) skills.

Impairment in control processes—