Neurocognitive Disorders

Neurocognitive Disorders

The patterns of cognitive aging challenge another assumption: that older people always lose the ability to think and remember. That is not true. Many older people are less sharp than they were, but most are still quite capable of intellectual activity. Others experience serious decline.

The Ageism of Words

It is undeniable that the rate of neurocognitive impairment increases with every decade after age 70. To understand that and prevent the worst of it, caution is needed in using words.

Senile means “old.” If senility is used to mean severe mental impairment, that falsely implies that age always brings intellectual failure. Dementia was a better term than senility for irreversible, pathological loss of brain functioning, but dementia also has inaccurate connotations (e.g., “mad” or “insane”).

neurocognitive disorders (NCDs) Impairment of intellectual functioning caused by organic brain damage or disease. NCDs may be diagnosed as major or mild, depending on the severity of symptoms. They become more common with age, but they are abnormal and pathological even in the very old.

The DSM-

Memory impairment is common in every cognitive disorder. Symptoms of neurocognitive disorders include many more impairments, especially in learning new material, using language, moving the body, and responding to people. Practical examples include getting lost, becoming confused about using common objects like a telephone or toothbrush, or having extreme emotional reactions.

The lines between normal age-

The problem of ageist terminology has been recognized internationally. In Japanese, the traditional word for neurocognitive disorder was chihou, translated as “foolish” or “stupid.” As more people reached old age, the Japanese decided on a new word, ninchihou, which means “cognitive syndrome” (George & Whitehouse, 2010). That is similar to the changes in English terminology over the past decades, from senility to dementia to neurocognitive disorder.

Mild and Major Impairment

Many instances of memory loss are not necessarily ominous signs of severe loss to come. Older adults who have significant problems with memory, but who still function well at work and home, might be diagnosed with mild NCD, formerly called mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Although some of them will develop major disorders, about half will be mildly impaired for decades or will regain cognitive abilities. For instance, a detailed study of African Americans diagnosed with MCI found that each year, 6 percent developed major losses but 18 percent reverted back to normal (S. Gao et al., 2013).

Many tests are designed to measure mild loss, including one that takes less than 10 minutes—

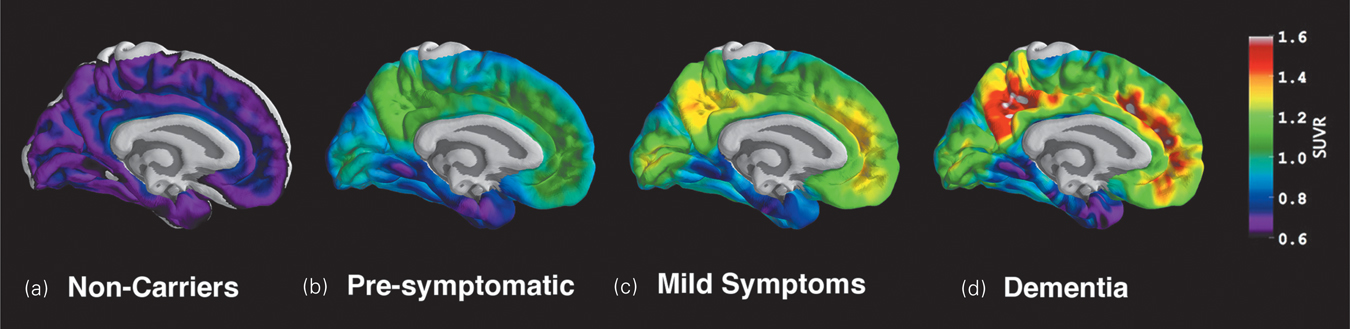

Many scientists seek biological indicators (called biomarkers, such as substances in the blood or cerebrospinal fluid) or brain indicators (as found in brain scans) that predict major memory loss. However, although abnormal scores on many tests (biological, neurological, or psychological) indicate possible problems, an examination of 24 such measures found no single test, and no combination of tests, to be 100 percent accurate (Ewers et al., 2012).

The final determinant of neurocognitive disorders is the clinical judgment of a professional who considers all the markers and symptoms—

Prevalence of NCD

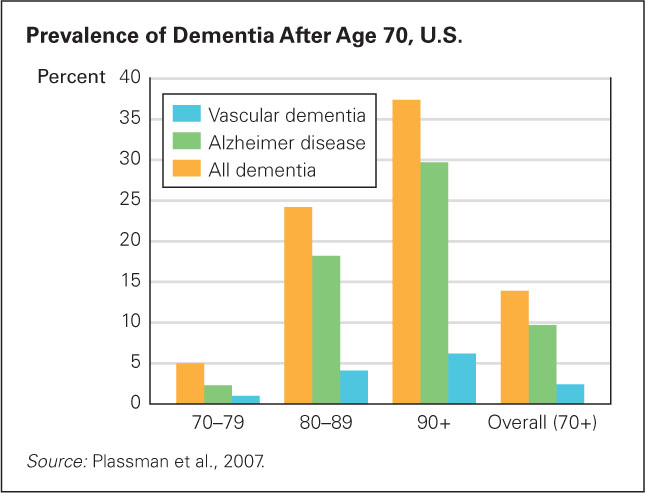

FIGURE 24.4

Not Everyone Gets It Most elderly people never experience a neurocognitive disorder. Among people in their 70s, only 1 person in 20 does, and even by age 90 or 100, most people still think well enough. Presented another way, the prevalent data sound more dire: Almost 4 million people in the United States have a major neurocognitive disorder. (This study used the former term, dementia.)As you remember from Chapter 23, ageism leads to presentation of statistics in ways that make younger adults recoil with horror. One example is in data about the rising numbers of old people with cognitive problems. We need a more rational understanding.

To find out how many people are truly suffering from cognitive disorders in their older years, researchers selected a representative sample of people 70 years of age and older from every part of the United States, interviewed and examined each one, and spoke with someone who knew them well (usually an immediate relative). They combined this information with test results, medical records, and clinical judgment, and found that 14 percent had some form of major impairment (Plassman et al., 2007) (see Figure 24.4). Extrapolated to the overall population, about 4 million U.S. residents have a serious neurocognitive disorder.

Rates vary by nation, from about 2 to 25 percent of elders, with an estimated 35 million people affected by NCD worldwide (Kalaria et al., 2008; WHO, 2010). Developing nations have lower rates, but that may be because people in the early stages are not counted or because health care overall is poor. (See Visualizing Development, p. 725)

How would poor health care lead to less, not more, impairment? Because many people die before any neurocognitive problems are apparent. People with diabetes, Parkinson’s, strokes, and heart surgery are more likely to lose intellectual capacity in old age, but in poor nations many people with those conditions die before age 70.

Improvements in health care can reduce cognitive impairment, even as the incidences rise. The three ideal public health goals are (1) better physical health, (2) less mental disorder, and (3) longer lives. That is becoming a reality in some nations.

In England and Wales the rate of dementia for people over age 65 was 8.3 percent in 1991 but only 6.5 percent in 2011 (Matthews et al., 2013). Sweden had a similar decline (Qie et al., 2011). In China, rates were much higher in rural areas than in urban ones, probably because rural Chinese had less education (Jia et al., 2014). This again suggests that NCD will be reduced as more people understand how to stay healthy.

A comparable survey has not been done in North America, but some signs suggest improvement. Of course, reduction in rate does not necessarily mean reduction in number, since more people live to old age. In England over the past 20 years, the number of people with dementia stayed about the same (Matthews et al., 2013) even while the rate has declined.

Genetics and social context affect rates, but it is not known by how much (Bondi et al., 2009). For example, more older women than men are diagnosed with neurocognitive disorders, which may be genetic, educational, or stress-

Alzheimer Disease

Alzheimer disease (AD) The most common cause of dementia, characterized by gradual deterioration of memory and personality and marked by the formation of plaques of beta-

In 1906, a physician named Dr. Alois Alzheimer performed an autopsy on a patient who had lost her memory. He found unusual material in her brain; he was uncertain whether it specified a distinct disease (George & Whitehouse, 2010). Others, convinced that he had discovered a disease, named it after him. In the past century, millions of people in every large nation have been diagnosed with Alzheimer disease (AD) (now formally referred to as major or mild NCD due to Alzheimer disease). In China, for example, 5.7 million people have Alzheimer disease (Chan et al., 2013).

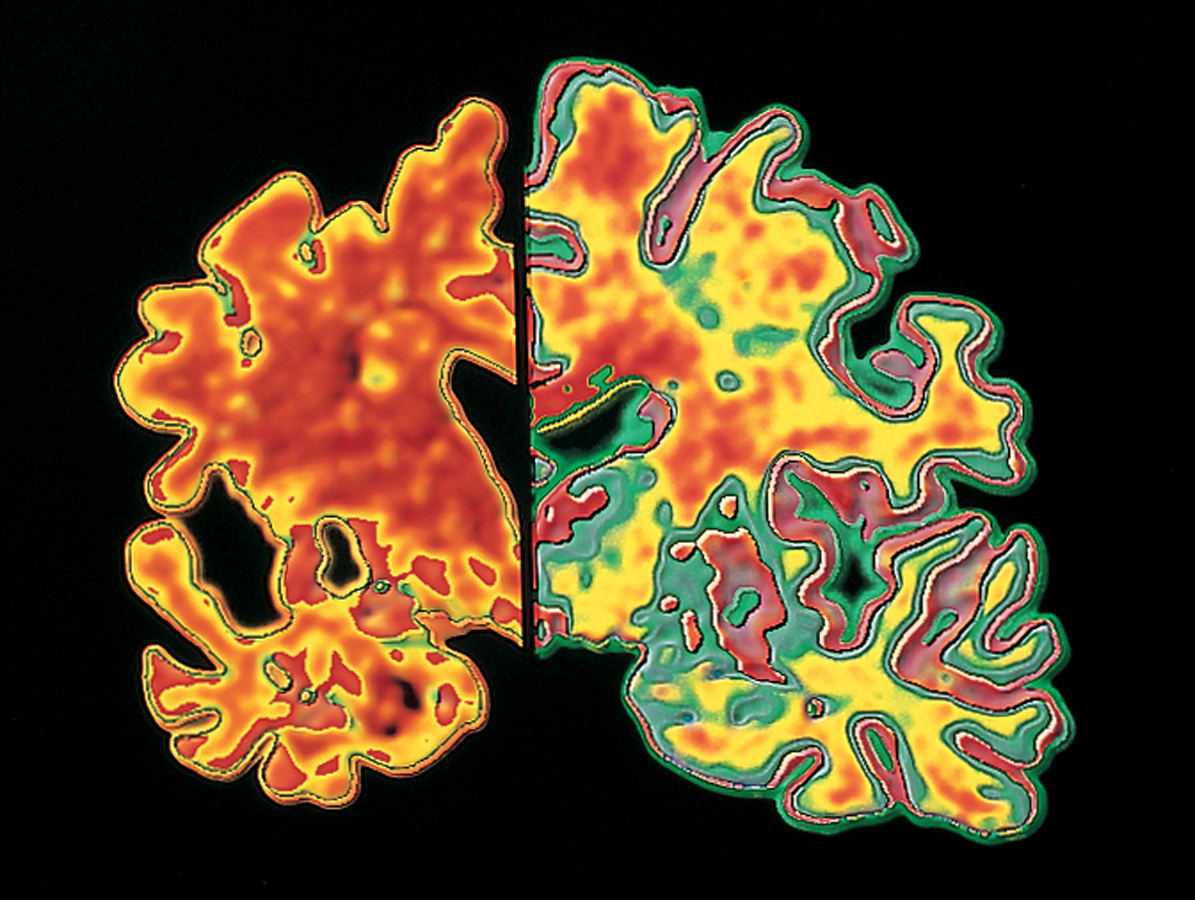

As Dr. Alzheimer discovered, autopsies reveal that some aging brains have many plaques and tangles in the cerebral cortex. These abnormalities destroy the ability of neurons to communicate with one another, causing severe cognitive loss.

plaques Clumps of a protein called beta-

tangles Twisted masses of threads made of a protein called tau within the neurons of the brain.

Plaques are clumps of a protein called beta-

Although finding massive brain plaques and tangles at autopsy proves that a person diagnosed with NCD had Alzheimer disease, between 20 and 30 percent of cognitively normal elders have, at autopsy, the same levels of plaques in their brains as people who had been diagnosed with AD (Jack et al., 2009). Possibly the normal elders had compensated by using other parts of their brains; possibly they were in the early stages, not yet suspected of having AD; possibly plaques are a symptom, not a cause.

Alzheimer disease is partly genetic. If it develops in middle age, the affected person either has trisomy-

Most cases begin much later, at age 75 or so. Many genes have some impact, including SORL1 and ApoE4 (allele 4 of the ApoE gene). People who inherit one copy of ApoE4 (as about one-

Especially for Genetic Counselors Would you perform a test for ApoE4 if someone asked for it?

Response for Genetic Counselors: A general guideline for genetic counselors is to provide clients with whatever information they seek, but because of both the uncertainty of diagnosis and the devastation of Alzheimer disease, the ApoE4 test is not available at present. This may change (as was the case with the test for HIV) if early methods of prevention and treatment become more effective.

Vascular NCD

The second most common cause of neurocognitive disorder is a stroke (a temporary obstruction of a blood vessel in the brain) or a series of strokes, called transient ischemic attacks (TIAs, or ministrokes). The interruption in blood flow reduces oxygen, destroying part of the brain. Symptoms (blurred vision, weak or paralyzed limbs, slurred speech, and mental confusion) suddenly appear.

vascular dementia (VaD) A form of neurocognitive disorder characterized by sporadic, and progressive, loss of intellectual functioning caused by repeated infarcts, or temporary obstructions of blood vessels, which prevent sufficient blood from reaching the brain.

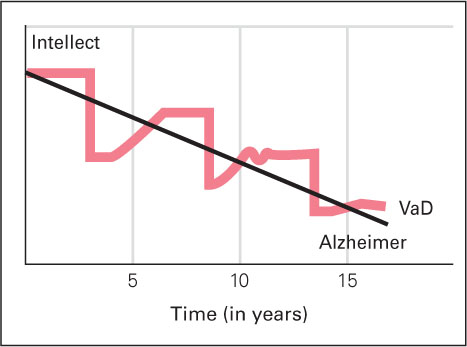

In a TIA, symptoms may vanish quickly, unnoticed. However, unless it is recognized and preventive action taken, another is likely. Repeated TIAs produce a type of NCD sometimes called vascular dementia (VaD), or multi-

FIGURE 24.5

The Progression of Two NCDs: Alzheimer Disease and Vascular Dementia Cognitive decline is apparent in both Alzheimer disease (AD) and vascular dementia (VaD). However, the pattern of decline for each disease is different. Victims of AD show steady, gradual decline, while those who suffer from VaD get suddenly worse, improve somewhat, and then experience another serious loss.Neurocognitive disorders caused by vascular disease are apparent in many of the oldest-

Frontal Lobe Disorders

frontal lobe disorder Deterioration of the amygdala and frontal lobes, which may be the cause of 15 percent of all dementias. (Also called frontotemporal lobar degeneration and, in the DSM-

Several types of neurocognitive disorders are called frontal lobe disorders, or frontotemporal lobar degeneration (Pick disease is the most common form). These disorders cause perhaps 15 percent of all cases of NCD in the United States. It is particularly likely to occur at relatively young ages (under age 70), unlike Alzheimer or vascular diseases, which typically begin later (Seelaar et al., 2011).

In frontal lobe disorders, parts of the brain that regulate emotions and social behavior (especially the amygdala and prefrontal cortex) deteriorate. Emotional and personality changes are the main symptoms (Seelaar et al., 2011). A loving mother with frontal lobe degeneration might reject her children, or a formerly astute businessman might invest in a harebrained scheme.

Frontal lobe problems may be worse than more obvious types of neurocognitive disease in that compassion, self-

threw away tax documents, got a ticket for trying to pass an ambulance, and bought stock in companies that were obviously in trouble. Once a good cook, he burned every pot in the house. He became withdrawn and silent, and no longer spoke to his wife over dinner. That same failure to communicate got him fired from his job.

[Grady, 2012, p. A1]

Finally, he was diagnosed with frontal lobe disorder. Ruth asked him to forgive her fury. It is not clear that he understood either her anger or her apology.

Although there are many forms and causes of frontal lobe disorders—

Other Disorders

Parkinson’s disease A chronic, progressive disease that is characterized by muscle tremor and rigidity, and sometimes dementia; caused by a reduction of dopa-

Many other brain diseases begin with impaired motor control (shaking when picking up a coffee cup, falling when trying to walk), not with impaired thinking. The most common of these is Parkinson’s disease, the cause of about 3 percent of all cases of NCD (Aarsland et al., 2005).

Parkinson’s disease starts with rigidity or tremor of the muscles as dopamine-

Lewy bodies Deposits of a particular kind of protein in the brain that interfere with communication between neurons; Lewy bodies cause neurocognitive disorder.

Another 3 percent of people with NCD in the United States suffer from an excess of Lewy bodies: deposits of a particular kind of protein in their brains. Lewy bodies are also present in Parkinson’s disease, but in Lewy body disorder they are more numerous and dispersed throughout the brain, interfering with communication between neurons. As a result, movement and cognition are both impacted. Motor effects are less severe than in Parkinson’s disease and memory loss is not as dramatic as in Alzheimer disease (Bondi et al., 2009). The main Lewy body symptom is loss of inhibition: A person might gamble or become hypersexual.

Comorbidity is common with all these disorders. For instance, most people with Alzheimer disease also show signs of vascular impairment (Doraiswamy, 2012). Parkinson, Alzheimer, and Lewy body disorders can occur together: People who have all three experience more rapid and severe cognitive loss (Compta et al., 2011).

Some other types of NCD begin in middle age or even earlier, caused by Huntington disease, multiple sclerosis, a severe head injury, syphilis, AIDS, or bovine spongiform encephalitis (BSE, or mad cow disease). Repeated blows to the head, even without concussions, can cause chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), which first causes memory loss and emotional changes (Voosen, 2013).

Although the rate of NCD increases dramatically with every decade after age 60, brain disease can occur at any age, as revealed by the autopsies of a number of young professional athletes. For them, prevention includes better helmets and fewer body blows. Already, tackling is avoided in professional (NFL) practices.

Changes like these have come too late for thousands of adults, including Derek Boogaard, a star National Hockey League enforcer, who died of a drug overdose at age 28. His autopsied brain showed traumatic brain injury, chronic traumatic encephalopathy.

For Boogaard, CTE may have been one cause of his drug addiction and would have become a major neurocognitive disorder if he had lived longer. Instead, NCD may have already occurred, undiagnosed. Another hockey player said of him, “His demeanor, his personality, it just left him. He didn’t have a personality anymore” (John Scott, quoted in Branch, 2011, p. B13). Obviously, senility and senescence are not synonyms for neurocognitive disorder.

Preventing Impairment

Since aging increases the rate of cognitive impairment, slowing down senescence may postpone major NCD, and ameliorating mild losses may prevent worse ones. That may have occurred in the decreasing rates of major NCD documented in England (Matthews et al., 2013).

Epigenetic research is particularly likely to lead to better prevention, because “the brain contains an epigenetic ‘hotspot’ with a unique potential to not only better understand its most complex functions, but also to treat its most vicious diseases” (Gräff et al., 2011, p. 603). Genes are always influential. Some are expressed, affecting development, and some are latent unless circumstances change. The reasons are epigenetic: Factors beyond the genes are crucial (Issa, 2011; Skipper, 2011).

The most important nongenetic factor is exercise. Because brain plasticity is lifelong, exercise that improves blood circulation not only prevents cognitive loss but also builds capacity and repairs damage. The benefits of exercise have been repeatedly cited in this text. Now we simply emphasize that physical exercise—

KOSTAS TSIRONIS/BLOOMBERG VIA GETTY IMAGES

Medication to prevent stroke also protects against neurocognitive disorders. In a Finnish study, half of a large group of older Finns were given drugs to reduce lipids in their system (primarily cholesterol). Years later, fewer of them had developed NCD than did a comparable group who were not given the drug (Solomon et al., 2010).

Avoiding specific pathogens is critical. For example, beef can be tested to ensure that it does not have BSE, condoms can protect against AIDS, syphilis can be cured with antibiotics. For most cognitive disorders, however, despite the efforts of thousands of scientists and millions of older people, no foolproof prevention or cure has been found. Avoiding toxins (lead, aluminum, copper, and pesticides) or adding supplements (hormones, aspirin, coffee, insulin, antioxidants, red wine, blueberries, and statins) have been tried as preventatives but have not proven effective in controlled, scientific research.

Thousands of scientists have sought to halt beta-

Among professionals, hope is replacing despair. Earlier diagnosis seems possible; many drug and lifestyle treatments are under review (Hampel et al., 2012; Lane et al., 2011). Hope comes from contemplating the success that has been achieved in combating other diseases. Heart attacks, for instance, were once the leading cause of death for middle-

As with heart disease, the first step in prevention and treatment of NCD is to improve overall health. High blood pressure, diabetes, arteriosclerosis, and emphysema all impair cognition, because they disrupt the flow of oxygen to the brain. Each type of neurocognitive disorder, each slowdown, and all chronic diseases interact, so progress in one area may reduce incidence and severity in another. A healthy diet, social interaction, and especially exercise decrease cognitive impairment of every kind, affecting brain chemicals and encouraging improvement in other health habits.

Early, accurate diagnosis, years before obvious symptoms appear, leads to more effective treatment. Drugs do not cure NCD, but some slow progression. Sometimes surgery or stem cell therapy is beneficial. The U.S. Pentagon estimates that more than 200,000 U.S. soldiers who were in Iraq or Afghanistan suffered traumatic brain injury, predisposing them to major neurocognitive disorder before age 60 (Miller, 2012). Measures to remedy their brain damage may help the aged as well.

FRANK RUMPENHORST/PICTURE-

Reversible Neurocognitive Disorder?

Care improves when everyone knows that a disease is undermining intellectual capacity. Accurate diagnosis is even more crucial when memory problems do not arise from a neurocognitive disorder. Brain diseases destroy parts of the brain, but many older people are thought to be permanently “losing their minds,” when a reversible condition is at fault.

Depression and Anxiety

The most common reversible condition that is mistaken for neurocognitive disorder is depression. Normally, older people tend to be quite happy; frequent sadness or anxiety is not normal. Ongoing, untreated depression increases the risk of dementia (Y. Gao et al., 2013).

Ironically, people with untreated anxiety or depression may exaggerate minor memory losses or refuse to talk. Quite the opposite reaction occurs with early Alzheimer disease, as victims are often surprised when they cannot answer questions, or with Lewy body or frontal lobe disorders, when people talk without thinking.

Specifics provide other clues. People with neurocognitive loss might forget what they just said, heard, or did because current brain activity is impaired, but they might repeatedly describe details of something that happened long ago. The opposite may be true for emotional disorders, when memory of the past is impaired but short-

Nutrition

Malnutrition and dehydration can also cause symptoms that may seem like brain disease. The aging digestive system is less efficient but needs more nutrients and fewer calories. This requires new habits, less fast food, and more grocery money (which many do not have).

Some elderly people deliberately drink less because they want to avoid frequent urination, yet adequate liquid in the body is needed for cell health. Since homeostasis slows with age, older people are less likely to recognize and remedy their hunger and thirst, and thus may inadvertently impair their cognition.

Beyond the need to drink water and eat vegetables, several specific vitamins have been suggested as decreasing the rate of dementia, including anti-

Indeed, well-

Polypharmacy

polypharmacy Refers to a situation in which elderly people are prescribed several medications. The various side effects and interactions of those medications can result in dementia symptoms.

At home as well as in the hospital, most elderly people take numerous drugs—

Unfortunately, recommended doses of many drugs are determined primarily by clinical trials with younger adults, for whom homeostasis usually eliminates excess medication (Herrera et al., 2010). When homeostasis slows down, excess may linger. In addition, most trials to test safety of a new drug exclude people who have more than one disease. That means drugs are not tested on many of the elderly who will use them.

The average elderly person in the United States sees a physician eight times a year (Schiller et al., 2012). Typically, each doctor follows “clinical practice guidelines,” which are recommendations for one specific condition. A “prescribing cascade” (when many interacting drugs are prescribed) may occur.

In one disturbing case, a doctor prescribed medication to raise his patient’s blood pressure, and another doctor, noting the raised blood pressure, prescribed a drug to lower it (McLendon & Shelton, 2011–

Another problem is that people of every age forget when to take which drugs (before, during, or after meals? after dinner or at bedtime?), a problem multiplied as more drugs are prescribed (Bosworth & Ayotte, 2009). Short-

Even when medications are taken as prescribed and the right dose reaches the bloodstream, drug interactions can cause confusion and memory loss. Cognitive side effects can occur with almost any drug, especially those drugs intended to reduce anxiety and depression. They often affect memory or reasoning.

Finally, following recommendations from the radio, friends, and television ads, many of the elderly try supplements, compounds, and herbal preparations that contain mind-

A CASE TO STUDY

Too Many Drugs or Too Few?

The case for medication is persuasive. Thousands of drugs have been proven effective, many of them responsible for longer and healthier lives. It is estimated that, on doctor’s orders, 20 percent of older people take 10 or more drugs on a regular basis (Boyd et al., 2005). Common examples of life-

In addition, many older people take supplements, drink alcohol, and swallow vitamins and other nonprescription drugs daily. The combination of doctor-

A 70-

Audrey couldn’t be trusted with the grandchildren anymore, so family visits were fewer and farther between. She rarely showered and spent most days sitting in a chair alternating between drinking, sleeping, and watching television. She stopped calling friends, and social invitations had long since ceased.

Audrey obtained prescriptions for Valium, a tranquilizer, and Placidyl, a sleep inducer. Both medications, which are addictive and have more adverse effects in patients over age 60, should only be used for short periods of time. Audrey had taken both medications for years at three to four times the prescribed dosage. She mixed them with large quantities of alcohol. She was a full-

Her children knew she had a problem, but they … couldn’t agree among themselves on the best way to help her. Over time, they became desensitized to the seriousness of her problem—

[Colleran & Jay, 2003, p. 11]

Audrey is a stunning example of the danger of ageist assumptions as well as of polypharmacy. Her children did not realize that she was capable of an intellectually and socially productive life.

The solution seems simple: Discontinue drugs. However, that may increase both disease and dementia. One expert warns of polypharmacy but adds that “underuse of medications in older adults can have comparable adverse effects on quality of life” (Miller, 2011–

For instance, untreated diabetes and hypertension cause cognitive loss. Lack of drug treatment for those conditions may be one reason why low-

Obviously, money complicates the issue: Prescription drugs are expensive, which increases profits for drug companies, but they can also reduce surgery and hospitalization, thus saving money. As one observer notes, the discussion about spending for prescription drugs is highly polarized, emotionally loaded, with little useful debate. A war is waged over the cost of prescriptions for older people, and it is a “gloves-

Which is it—

The current policy is to let the doctor and the patient decide. Even family members are not consulted or informed unless the patient agrees. That seems like a wise protection of privacy. But remember Audrey.

SUMMING UP

Many elderly people experience some cognitive impairment, which may lead to neurocognitive disorder (NCD), still often referred to as dementia. Among the many types of NCD, each with distinct symptoms, are four common diseases of the elderly: Alzheimer, vascular, frontal lobe, and Parkinson’s. No cure for NCD has yet been found, but treatment may slow its progression and sometimes prevent its onset. The inclusion of minor NCD in the DSM-