Activities in Late Adulthood

Activities in Late Adulthood

Many elders complain that they do not have enough time each day to do all they want to do. This might surprise young college students, who see few gray hairs at sports events, political rallies, job sites, or midnight concerts. But most of the elderly are far from inactive.

Working

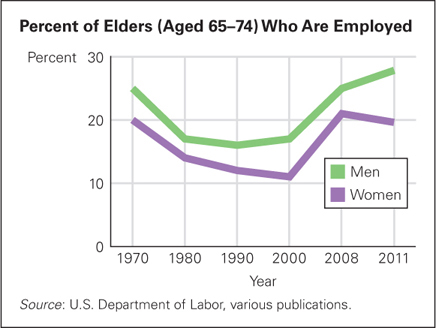

Work provides social support and status. Many elders are reluctant to give that up (see Figure 25.4); others enjoy retirement. [Lifespan Link: The importance of work is discussed in Chapter 22.]

FIGURE 25.4

Along with Everyone Else Although younger adults might imagine that older people stop work as soon as they can, this is clearly not the case for everyone.Paid Work

Past employment history affects the current health and happiness of older adults (Wahrendorf et al., 2013). Those who lost their jobs because of structural changes (a factory closing, a corporate division eliminated) are, decades later, likely to be in poor health (Schröder, 2013). Income matters as well: Those who have sufficient savings from prior employment and an adequate pension are much more likely to enjoy old age.

© RICHARD NOWITZ/NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC SOCIETY/CORBIS

In every nation the employment rate for older workers has risen since 2005, primarily because many workers hold on to their jobs, worried about the cost of not working. Some private pensions have been eliminated, and many governments are reducing national pensions. For example, in 2010 the French raised the pension age from 60 to 62, a move reversed in 2012 for those who have worked at least 40 years. In the United States, full Social Security benefits begin at age 65 for those born before 1938, but now those born after 1959 must be age 67 for full Social Security.

The decision to quit work is affected by dozens of factors; some workers retire at age 55, and others are working full time in their 70s. Most retire in their 60s. For example, in 2012 only 13 percent of Canadians over age 64 were employed (Statistics Canada).

Nonunionized low-

Retirement

Adequate income and poor health are the two primary reasons some people retire relatively early, younger than age 60 (Alavinia & Burdorf, 2008). Job dissatisfaction is also a factor, as is parenthood—

Many retirees hope to work part time or become self-

When retirement is precipitated by poor health or fading competence, it correlates with illness (A. Shapiro & Yarborough-

Volunteer Work

Volunteering offers some of the benefits of paid employment (generativity, social connections, less depression). Longitudinal as well as cross-

As self theory would predict, volunteer work attracts older people who always were strongly committed to their community and had more social contacts (Pilkington et al., 2012). Beyond that, volunteering itself protects health, even for the very old (Okun et al., 2011). For example, one study of people in rural areas who did not drive reported that the death rate among those who volunteered was half the rate of those who did not volunteer (S. J. Lee et al., 2011).

Culture or national policy affects volunteering: Nordic elders (in Sweden and Norway) volunteer more often than their Mediterranean counterparts (in Italy and Greece), differences that persist when illness is taken into account (Hank & Erlinghagen, 2006). The microsystem also has an effect. Being married to a volunteer makes a person more likely to volunteer. Volunteering fosters social connections, which improves health as well as encourages more volunteering (Pilkington et al., 2012).

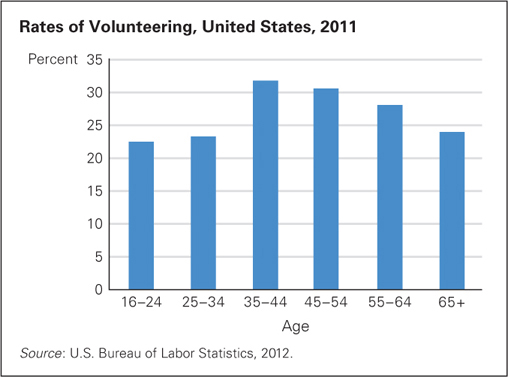

The data reveal two areas of concern, however. First, older retirees may be less likely to volunteer than middle-

Especially for Social Workers Your agency needs more personnel but does not have money to hire anyone. Should you go to your local senior-

Response for Social Workers: Yes, but be careful. If people want to volunteer and are just waiting for an opportunity, you will probably benefit from their help and they will also benefit. But if you convince reluctant seniors to help you, the experience may benefit no one.

FIGURE 25.5

Official Volunteers As you can see, older adults volunteer less often than do middle-Perhaps the definition of volunteering is too narrow. Indeed, most of the elderly give money and time to relatives. A longitudinal study of the Wisconsin high school graduates of 1957 found that, by late adulthood, 96 percent of the women and 92 percent of the men provided help to someone else, not including their spouse (Kahn et al., 2011). This study did not include financial help; if it did, the rate would be almost 100 percent. That bodes well: People of all ages are happier when they help other people.

Home Sweet Home

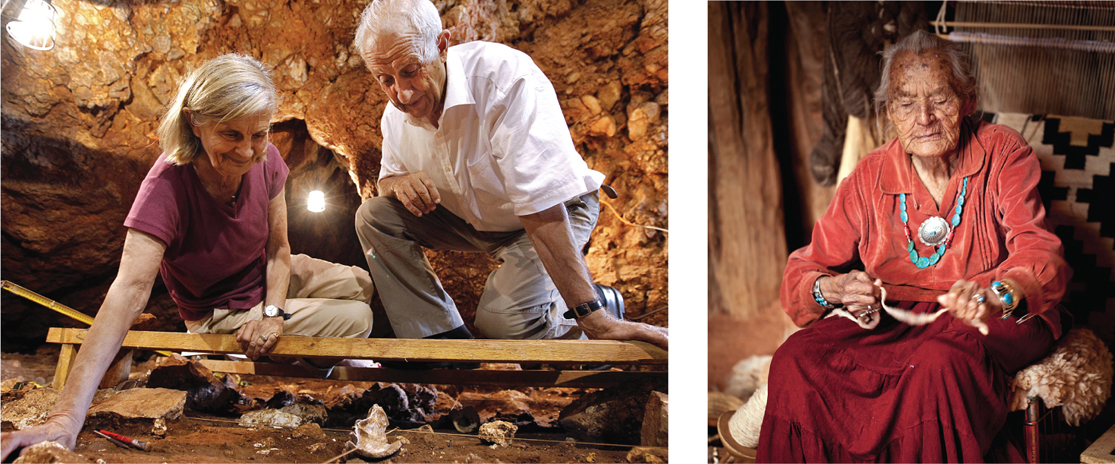

One of the favorite activities of many retirees is caring for their own homes. Typically, both men and women do more housework and meal preparation (less fast food, more fresh ingredients) after retirement (Luengo-

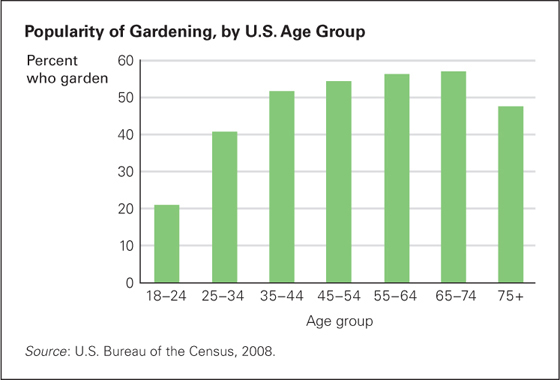

Gardening is popular: More than half the elderly in the United States do it (see Figure 25.6). Tending flowers, herbs, and vegetables is productive because it involves both exercise and social interaction (Schupp & Sharp, 2012).

FIGURE 25.6

Dirty Fingernails Almost three times as many 60-age in place To remain in the same home and community in later life, adjusting but not leaving when health fades.

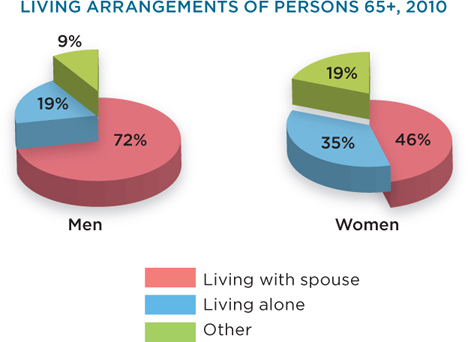

In keeping up with household tasks and maintaining their property, many older people prefer to age in place rather than move. That is the plan of many middle-

If they must move, most elders want to remain nearby, perhaps in a smaller apartment with an elevator, but not in another city or state. That is wise: Elders fare best surrounded by long-

The preference for aging in place is evident in state statistics. Of the 50 states, Florida has the largest percentage of people over age 65, but the next three states highest in that proportion—

Fortunately, some houses are built or remodeled to suit aging people. About 4,000 consultants are now certified by the National Association of Homebuilders to advise about universal design. [Lifespan Link: Universal design is defined in Chapter 23.] That includes dozens of details that make a home livable for people who find it hard to reach the top shelves, to climb stairs, to respond quickly to the doorbell. Non-

naturally occurring retirement community (NORC) A neighborhood or apartment complex whose population is mostly retired people who moved to the location as younger adults and never left.

A neighborhood or an apartment complex can become a naturally occurring retirement community (NORC), where young adults stayed as they aged. People in NORCs are often content to live alone, after children left and partners died. They enjoy home repair, housework, and gardening partly because their lifelong neighbors notice the new curtains, the polished door, the blooming rosebush.

NORCs can be granted public money to replace after-

Public and private institutions can encourage aging in place (A. E. Smith, 2009). That is true for my friend Doris, described in this chapter’s introduction as having “many meetings, appointments, and social engagements.” She lives alone and has been a widow for decades. She is actively engaged in many organizations, and the community in which she has lived for 50 years knows and appreciates her. (Visualizing Development, p. 741, provides an overview of living arrangements after age 65.)

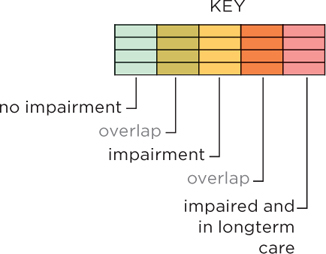

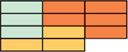

VISUALIZING DEVELOPMENT

Life After 65: Living Independently

Most people who reach age 65 not only survive a decade or more, but will also live independently.

AGE 65 Of 100 people:

87 will survive another decade. Most will spend that time caring for all their basic needs. But 35 will be unable to take care of at least one instrumental activity of daily living (IADL) like household chores, shopping, or taking care of finances, or one activity of daily living (ADL) like bathing, dressing, eating, or getting in and out of bed. And 16 are so impaired that they are also in a long term care situation like a nursing home.

AGE 75 Of the 87 people who survived from age 65:

56 will survive another decade. About half will not need help caring for their basic needs. But 43 will be unable to take care of at least one instrumental activity of daily living (IADL) like household chores, shopping, or taking care of finances, or one activity of daily living (ADL) like bathing, dressing, eating, or getting in and out of bed. And 20 are so impaired that they are also in a long-

AGE 85 Of the 56 people who survived from age 75:

Only 11 will survive another decade. And most need help caring for their basic needs. 42 will be unable to take care of at least one instrumental activity of daily living (IADL) like household chores, shopping, or taking care of finances, or one activity of daily living (ADL) like bathing, dressing, eating, or getting in and out of bed. And 24 are so impaired that they are also in a long-

AGE 95

Those who reach 95 tend to be unusually healthy and usually live for about 4 more years. Almost three-

With whom?Only about 15 percent of those over age 65 move in with an adult child or live in a nursing home or hospital.

SOURCES & CREDITS LISTED ON P. SC-

|

Where?Not necessarily in a warm state or with caregivers.

SOURCE: US CENSUS BUREAU, 2011

|

Religious Involvement

Older adults attend fewer religious services than do the middle-

- Religious prohibitions encourage good habits (e.g., less drug use).

- Faith communities promote caring relationships.

- Beliefs give meaning for life and death, thus reducing stress (Atchley, 2009; Lim & Putnam, 2010).

Religious identity and institutions are especially important for older members of minority groups, many of whom are more strongly committed to their religious heritage than to their national or ethnic background. A nearby house of worship, with familiar words, music, and rituals, is one reason American elders prefer to age in place.

Faith may explain an oddity in mortality statistics, specifically in suicide data (Chatters et al., 2011). In the United States, suicide after age 65 among elderly European American men occurs 50 times more often than among African American women. A possible explanation is that African American women’s religious faith is often very strong, making them less depressed about their daily lives (Colbert et al., 2009).

Especially for Religious Leaders Why might the elderly have strong faith but poor church attendance?

Response for Religious Leaders: There are many possible answers, including the specifics of getting to church (transportation, stairs), physical comfort in church (acoustics, temperature), and content (unfamiliar hymns and language).

Political Activism

It is easy to imagine that elders are not political activists. Fewer older people turn out for rallies, and only about 2 percent volunteer in political campaigns. In 2011, only 7 percent of U.S. residents older than 65 gave time for any political, civic, international, or professional group (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2012b). This is not good news, since democracy depends on involvement.

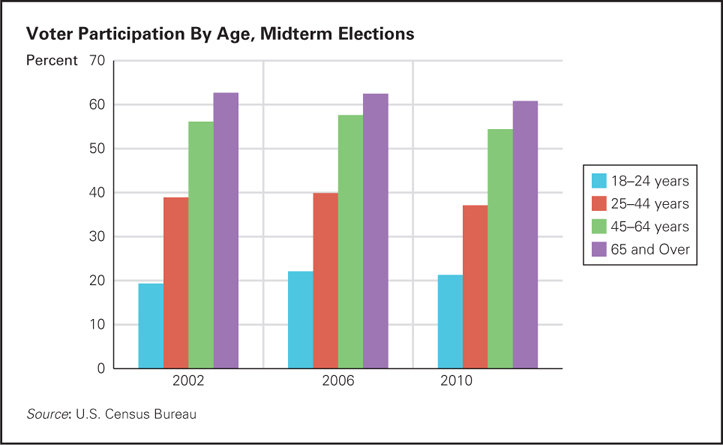

By other measures, however, the elderly are very political. More than any other age group, they write letters to their representatives, identify with a political party, and vote (see Figure 25.7).

FIGURE 25.7

When It Counts People over age 64 vote three times as often as those under age 25 when voting matters most—In addition, the elderly are more likely than younger adults to keep up with the news. For example, the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press periodically asks U.S. residents questions on current events. The elderly always best the young. They also know political history. In 2011, elders (65 and older) beat the youngest (aged 18 to 30) by a ratio of about 3-

Many government policies affect the elderly, especially those regarding housing, pensions, prescription drugs, and medical costs. However, members of this age group do not necessarily vote their own economic interests, or vote as a bloc. Instead they are divided on most national issues, including global warming, military conflicts, and public education.

Political scientists believe the idea of “gray power” (that the elderly vote as a bloc) is a myth, promulgated to reduce support for programs that benefit the old (Walker, 2012). Given that ageism zigzags from hostile to benign—

SUMMING UP

The elderly remain active in many ways, sometimes staying in the labor force when it is not financially necessary, but more often retiring in order to do things they enjoy.

Some of the elderly volunteer, benefiting their own health as well as their community. Almost all care for neighbors and family members if they can. Elders prefer to “age in place,” not moving from their community. Many keep their home in good repair and their garden flourishing. They also tend to be devout, politically active (at least in voting), and knowledgeable about current events and political issues. The idea that they exert “gray power” is a myth: They do not vote as a bloc, even on issues that directly concern them.