Friends and Relatives

Friends and Relatives

Humans are social animals, dependent on one another for survival and drawn to one another for joy. This is as true in late life as in infancy and at every stage in between.

Every person travels through life with their social convoy. Thus companions are particularly important in old age. As socioemotional theory predicts, the size of the social circle may shrink with age, but close relationships become more crucial.

VIKTOR DRACHEVA/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

Bonds formed over the years allow people to share triumphs and tragedies with others who understand. Siblings, old friends, and spouses are ideal convoy members. [Lifespan Link: The social convoy is discussed in Chapter 22.]

Long-Term Partnerships

For most of the current cohort of elders, their spouse is the central convoy member, a buffer against the problems of old age. Married older adults are healthier, wealthier, and happier than unmarried people their age. Spouses affect each other: One healthy and happy partner improves the other’s well-

Obviously, not every marriage is good: About one in every six long-

Older couples have learned how to disagree, resolving conflicts in discussions, not fights. I know one example personally.

Irma and Bill are both politically active, proud parents of two adult children, devoted grandparents, and up on current events. They seem happily married and they cooperate admirably when caring for their 2-

Outsiders might judge many long-

One crucial factor is that the challenges of child rearing, home ownership, economic crises, and so on require cooperation. The importance of past sharing is suggested by research that finds that older husbands and wives with mutual close friends are more likely to help each other if special needs arise (Cornwell, 2012).

Given the importance of relationship building over the life span, it is not surprising that elders who are disabled (e.g., have difficulty walking, bathing, and so on) are less depressed and anxious if they are in a close marital relationship (Mancini & Bonanno, 2006). A couple together can achieve selective optimization with compensation: The one who is bedbound but alert can keep track of what the mobile but confused one must do, for instance.

Relationships with Younger Generations

In past centuries, many adults died before their grandchildren were born. For 10-

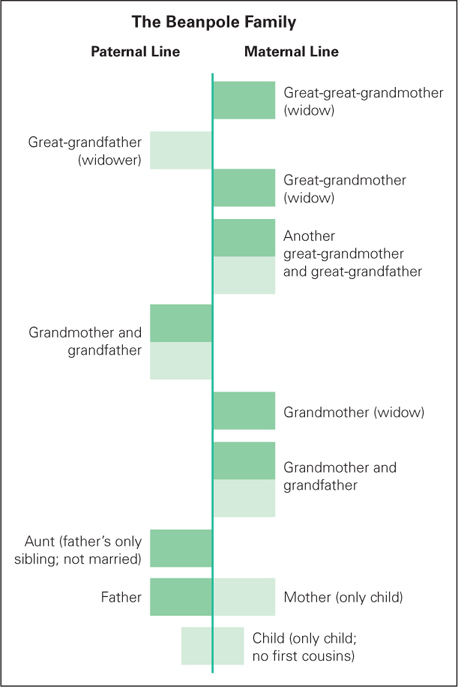

Since the average couple now has fewer children, the beanpole family, representing multiple generations but with only a few members in each, is becoming more common (Murphy, 2011) (see Figure 25.8). Some of the youngest have no cousins, brothers, or sisters but a dozen elderly relatives.

FIGURE 25.8

Many Households, Few Members The traditional nuclear family consists of two parents and their children living together. Today, as couples have fewer children, the beanpole family is becoming more common. This kind of family has many generations, each typically living in its own household, with only a few members in each generation.Intergenerational Support

filial responsibility The obligation of adult children to care for their aging parents.

For the most part, family members support one another. As you remember, familism prompts family caregiving among all the relatives. One manifestation is filial responsibility, the obligation of adult children to care for their aging parents. This is a value in every nation, stronger in some cultures than in others (Saraceno, 2010).

As family size shrinks, many older parents continue to feel responsible for their grown children. This can strain a long-

When my daughter divorced, they nearly lost the house to foreclosure, so I went on the loan and signed for them. But then again they nearly foreclosed, so my husband and I bought it…. So now I have to make the payment on my own house and most of the payment on my daughter’s house, and that is hard…. I am hoping to get that money back from our daughter, to quell my husband’s sense that the kids are all just taking and no one is giving back. He sometimes feels used and abused.

[quoted in Meyer, 2012, p. 83]

Emotional support between older adults and their grown children brings additional complexities, often increasing when money is less needed (Herlofson & Hagestad, 2012). Expectations vary. Some children want and others reject emotional help, and some elders resent exactly the same behaviors that other elders expect from their children—

Research finds no evidence that recent changes in family structure (including divorce) reduce the sense of filial responsibility. One study found that younger cohorts (born in the 1950s and 1960s) endorsed more responsibility toward older generations, “regardless of the sacrifices involved,” than did earlier cohorts (born in the 1930s and 1940s) (Gans & Silverstein, 2006).

Likewise, almost all elders believe the older generation should help the younger ones, although specifics vary by culture. When the government provides significant financial help for the aged (housing, pensions, and so on), the generations are more involved with each other than when government support is minimal (Herlofson & Hagestad, 2012).

In the United States, every generation values independence. That is why, after midlife and especially after the death of their own parents, members of the older generation are less likely to agree that children should provide substantial care for their parents and more likely to strive to be helpful to their children. A team who has studied this phenomenon suggests that adults of all ages like to be needed more than needy (Gans & Silverstein, 2006).

This may not be true in Asian cultures. Often the first-

Intergenerational Tensions

Although elderly people’s relationships with members of younger generations are usually positive, they can also include tension and conflict. In some families intergenerational respect and harmony abound, whereas in others relatives refuse to see each other. Each culture and each family has patterns and expectations regarding interactions between generations (Herlofson & Hagestad, 2011). Some conflict is common.

A good relationship with successful grown children enhances a parent’s well-

It is a mistake to think of the strength of the relationship as merely the middle generation paying back the older one for past sacrifices. Instead, family norms—

- Assistance arises from both need and ability to provide.

- Frequency of contact is related to geographical proximity, not affection.

- Love is influenced by childhood memories.

- Sons feel stronger obligation; daughters feel stronger affection.

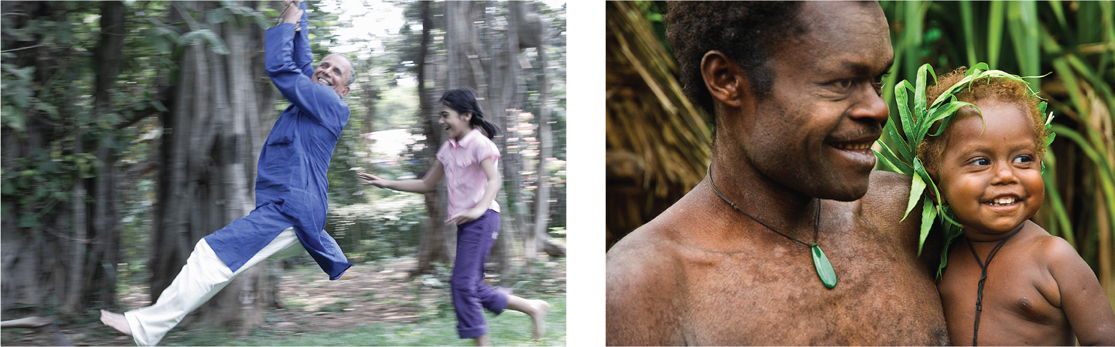

Grandparents and Great-Grandparents

Eighty-

As with parents and children, specifics of the grandparent–

Brian and Brianna are twins and are turning 13 years old this coming June. Over the spring break my family celebrated my grandmother’s 80th birthday and I overheard the twins’ talking about how important it was for them to still have grandma around because she was the only one who would give them money if they really wanted something their mom wasn’t able to give them…. I lashed out…how lucky we were to have her around and that they were two selfish little brats…. Now that I am older, I learned to appreciate her for what she really is. She’s the rock of the family, and “the bank” is the least important of her attributes now.

[Giovanna, 2010]

© ATLANTIDE PHOTOTRAVEL/CORBIS

Grandparents fill one of four roles:

- Remote grandparents (sometimes called distant grandparents) are emotionally distant from their grandchildren. They are esteemed elders who are honored, respected, and obeyed, expecting to get help whenever they need it.

- Companionate grandparents (sometimes called “fun-

loving” grandparents) entertain and “spoil” their grandchildren—especially in ways that the parents would not. - Involved grandparents are active in the day-

to- day lives of their grandchildren. They live near them and see them daily. - Surrogate parents raise their grandchildren, usually because the parents are unable or unwilling to do so.

Currently in developed nations, most grandparents are companionate, partly because all three generations expect them to be companions, not authorities. Contemporary elders usually enjoy their own independence. They provide babysitting and financial help but not advice or discipline (May et al., 2012). If grandparents become too involved and intrusive, parents tend to be forgiving but not appreciative (Pratt et al., 2008).

When grandparents become surrogates, the family structure is called the skipped generation because the middle generation is absent. The number of such grandparents is rising; it was 2.8 million in the United States in 2010. Social workers often seek grandparents for kinship foster care because foster children fare as well as or better with grandparents than with nonrelatives, but surrogate parenting is stressful for every generation.

One reason is that both old and young are sad about the missing middle generation; another is that difficult grandchildren (such as drug-

Furthermore, children of skipped-

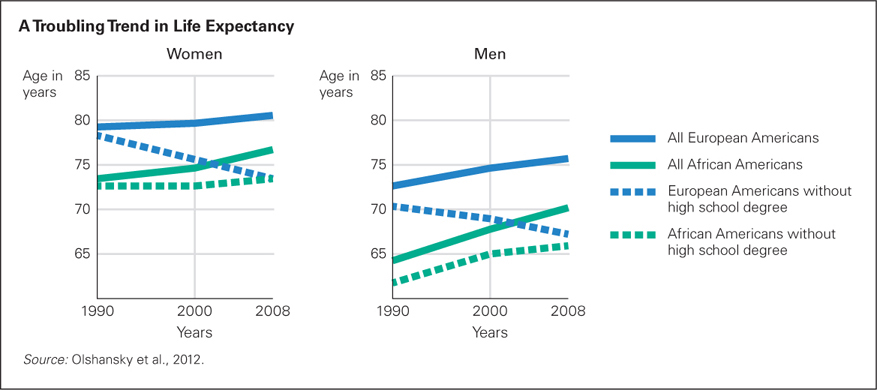

FIGURE 25.9

Too Young to Die Medical advances and improving health habits mean that most adults live longer than their parents did: The average life span has increased every decade for both sexes, for all ethnic groups, in every nation. However, in the United States those without a high school diploma find that steady work is increasingly scarce, which takes a toll on survival.But before concluding that grandparents suffer when they are responsible for grandchildren, consider China, where many grandparents become full-

However, skipped-

Not until my grandson was born did I realize that babies are actually miniature angels assigned to break through our knee-

[Golden, 2010, p. 125]

Friendship

Friendship networks typically become smaller with each decade. Emerging adults tend to average the most friends. By late adulthood, the number of people considered friends is notably smaller than it was earlier in life (Wrzus et al., 2013). Added to the normal shrinkage are two circumstances: Some older friends die, and retirement usually means losing contact with most work friends. Many older adults consider their spouse or grown children their best friends. This may create problems in the future.

Based on several U.S. Bureau of the Census documents, it appears that approximately 90 percent of people older than 75 in the United States in 2010 had been married, making this oldest generation the most-

Obviously, the next cohort of elders will include far fewer married people. Furthermore, more middle-

Not necessarily. Recent data finds that the young-

This is not to say that recent widowhood or divorce is easy, although widowhood is not as hard if one’s mate was seriously ill for years or if the marriage was not a close one (Schann, 2013). Similarly, losing a close friend, through death or relocation, is difficult.

However, elderly people who have spent years without a romantic partner usually have close friendships, meaningful activities, and social connections that keep them busy and happy (DePaulo, 2006). A study of 85 single elders found that their level of well-

Successful aging requires that people not be socially isolated, and many elders who have lived in the same community for years have found long-

SUMMING UP

Social connections are crucial for people at every age, including late adulthood. Long-