What Theories Do

What Theories Do

Every theory is an explanation of facts and observations, a set of concepts and ideas that organize the confusing mass of experiences that each of us encounters every minute. Some theories are idiosyncratic, narrow, and useless to anyone except the people who thought of them. Others are much more elaborate and insightful, such as the major theories described in this chapter that focus on human development over the life span.

developmental theory A group of ideas, assumptions, and generalizations that interpret and illuminate the thousands of observations that have been made about human growth. A developmental theory provides a framework for explaining the patterns and problems of development.

A developmental theory is a systematic statement of general principles that provides a framework for understanding how and why people change as they grow older. Facts and observations are connected to patterns and explanations, weaving the details of life into a meaningful whole. A developmental theory is more than a hunch or a hypothesis, and is far more comprehensive than my childish theorizing about bride dolls. Developmental theories provide insights that are both broad and deep, and they are therefore more comprehensive than the many observations and ideas from which they arise.

As an analogy, imagine building a house. A person could have a heap of lumber, nails, and other materials, but without a plan and labor the heap cannot become a building. Furthermore, not every house is alike: People have theories (usually not explicit) about houses that lead to preferences for the number of stories, bedrooms, entrances, and so on. Likewise, the observations and empirical studies of human development are essential raw materials, but theories put them together.

Kurt Lewin (1943) once quipped, “Nothing is as practical as a good theory.” Like many other scientists, he knew that theories can be insightful. Of course, theories differ; some are less comprehensive or adequate than others, some are no longer useful, some reflect one culture but not another. Nevertheless without them we have only a heap.

Questions and Answers

As we saw in Chapter 1, the first step in the science of human development is to pose a question, which often springs from a developmental theory. Among the thousands of important questions are the following, each central to one of the five theories described in this chapter:

- Does the impact of early experience—

of breast- feeding or attachment or abuse— linger into adulthood, even if the experience is seemingly forgotten? - Does learning depend on specific encouragement, punishment, and role models?

- Do children develop morals, even if they are not taught right from wrong?

- Does culture guide behavior?

- Is survival a basic instinct, underlying all personal and social decisions?

Each of these five questions is answered “yes” by, in order, psychoanalytic theory, behaviorism, cognitive theory, sociocultural theory, and the two universal theories, humanism and evolutionary theory. Each question is answered “no” or “not necessarily” by several others. For every answer, more questions arise: Why or why not? When and how? So what? This last question is crucial; the implications and applications of the answers affect everyone’s daily life.

To be more specific about what theories do:

- Theories produce hypotheses.

- Theories generate discoveries.

- Theories offer practical guidance.

A popular book of child-

I don’t want this…. I want a better one—

[p. 103]

Reactions to Chua’s book have been either very positive or very negative. Six months after the book was published, of the first 500 reader reviews on Amazon, 42 percent gave it the highest ratings, 23 percent the lowest, and the three ratings between high and low averaged only 12 percent each. Explaining these reactions, one professional reviewer wrote:

There was bound to be some pushback. All the years of nurturance overload simply got to be too much. The breast-

[Warner, 2011, p. 11]

Chua was surprised at the reactions, arguing that many people misinterpreted what she wrote (2011). Some of the positive comments from readers say that the book is a provocative memoir, not necessarily to be followed step by step. That makes it more like a theory than a parenting manual.

Chua’s narrative shows that her strategies do not always work as she hoped. But Tiger Mother illustrates one fact: Everyone has theories about development, some promoted with fierce intensity. For all of us, opinions about how to respond to children, adolescents, and adults often can be traced to the five theories that we will soon describe.

Facts and Norms

norm An average, or standard, measurement, calculated from the measurements of many individuals within a specific group or population.

A norm is an average or usual event or experience. It is related to the word “normal,” although it has a slightly different meaning. For instance, my cousin’s bride dress had a long white veil because in Western culture it is a norm for brides to wear white, symbolizing purity, but in Asian culture brides wear red, symbolizing celebration.

To be abnormal (not normal) implies that something is wrong, but norms are not meant to be right or wrong. A norm is an average—

Do not confuse theories with norms or facts. Theories raise questions and suggest hypotheses, and they lead to research to gather empirical data. [Lifespan Link: The scientific method is discussed in Chapter 1.] Those data are facts that suggest conclusions, which may verify or refute a theory, although other interpretations of the data and new research to investigate the theory are always possible.

Thus, theories are neither true nor false. Ideally, they are provocative and useful, leading to hypotheses and exploration. For example, some people dismiss Darwin’s theory of evolution as “just a theory,” while others believe it is a fact that explains all of nature since the beginning of time. No and no. Good theories should neither be dismissed as wrong nor equated with facts. Instead, theories deepen thought; they are useful (like a house plan), provoking insight, interpretation, and research.

As already explained, developmental theories are comprehensive and detailed, unlike the simple theories of children or the implicit theories that underlie the customs and assumptions of each culture. But to clarify the distinction between theory and fact, we return to the simple theory of the bride doll. My bitterness was one outcome of a dominant theory in my childhood culture—

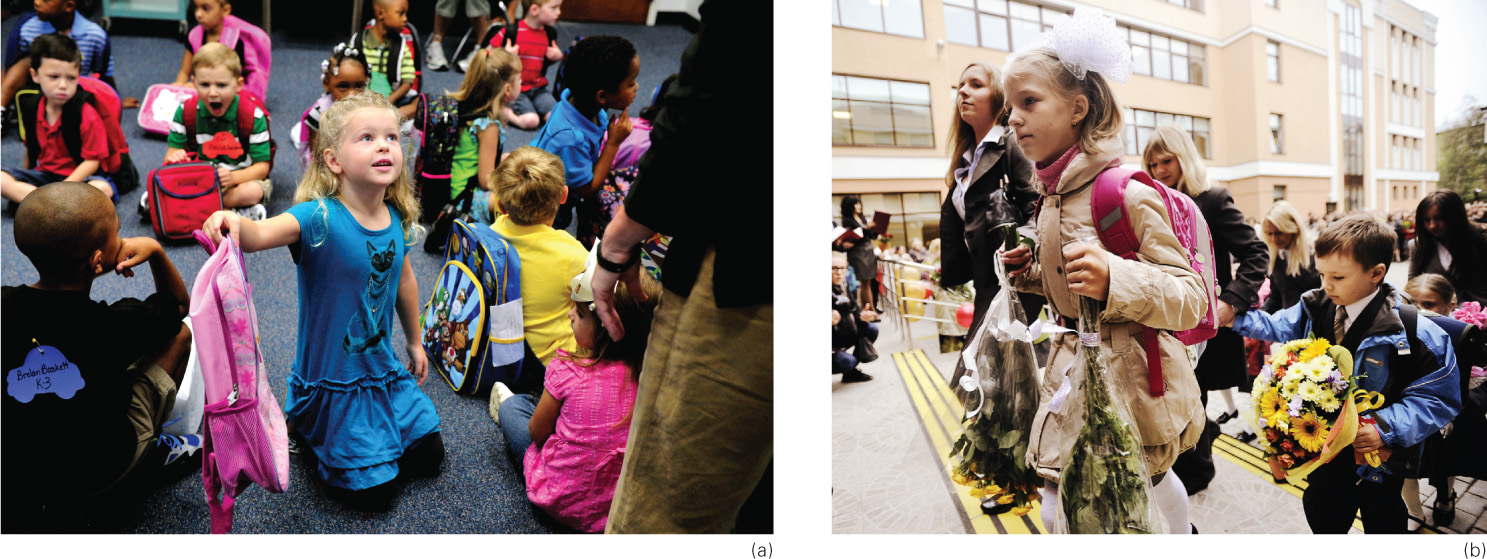

ASTAPKOVICH VLADIMIR ITAR-

The pro-

True to the dominant theory of my childhood, I fantasized about my wedding, named my seven possible children, and never imagined that maintaining a marriage and raising children was anything but “happy ever after.” Norms have changed, reflected in statistics as well as research that singleton children (no longer called “only”) are often high achievers with successful lives (Falbo et al., 2009), and that adults who never marry are often quite happy and accomplished. [Lifespan Link: Single adults are described in Chapter 22.]

Some say that the pro-

Obviously, science is needed. Theories are not facts, and “each theory of developmental psychology always has a view of humans that reflects philosophical, economic, and political beliefs” (Miller, 2011, p. 17). Scientists question norms, develop hypotheses, and design studies. That leads to conclusions that undercut some theories and modify others, to the benefit of all.

Without developmental theories, we would be merely reactive and bewildered, adrift and increasingly befuddled, blindly following our culture and our prejudices, less able to help anyone with a developmental problem.

SUMMING UP

Theories provide a framework for organizing and understanding the thousands of observations and daily behaviors that occur in every aspect of development. Theories are not facts, but they allow us to question norms, suggest hypotheses, and provide guidance. Thus, theories are practical and applied: They frame and organize our millions of experiences.