Birth

Birth

About 38 weeks (266 days) after conception, the fetal brain signals the release of hormones, specifically oxytocin, which prepares the fetus for delivery and starts labor, as well as increases the mother’s urge to nurture the baby. The average baby is born after 12 hours of active labor for first births and 7 hours for subsequent births, although often birth takes twice or half as long, with biological, psychological, and social circumstances all significant. The definition of “active” labor varies, which is one reason some women believe they are in active labor for days and others say 10 minutes.

FRANK HERHOLDT/GETTY IMAGES

Birthing positions also vary—

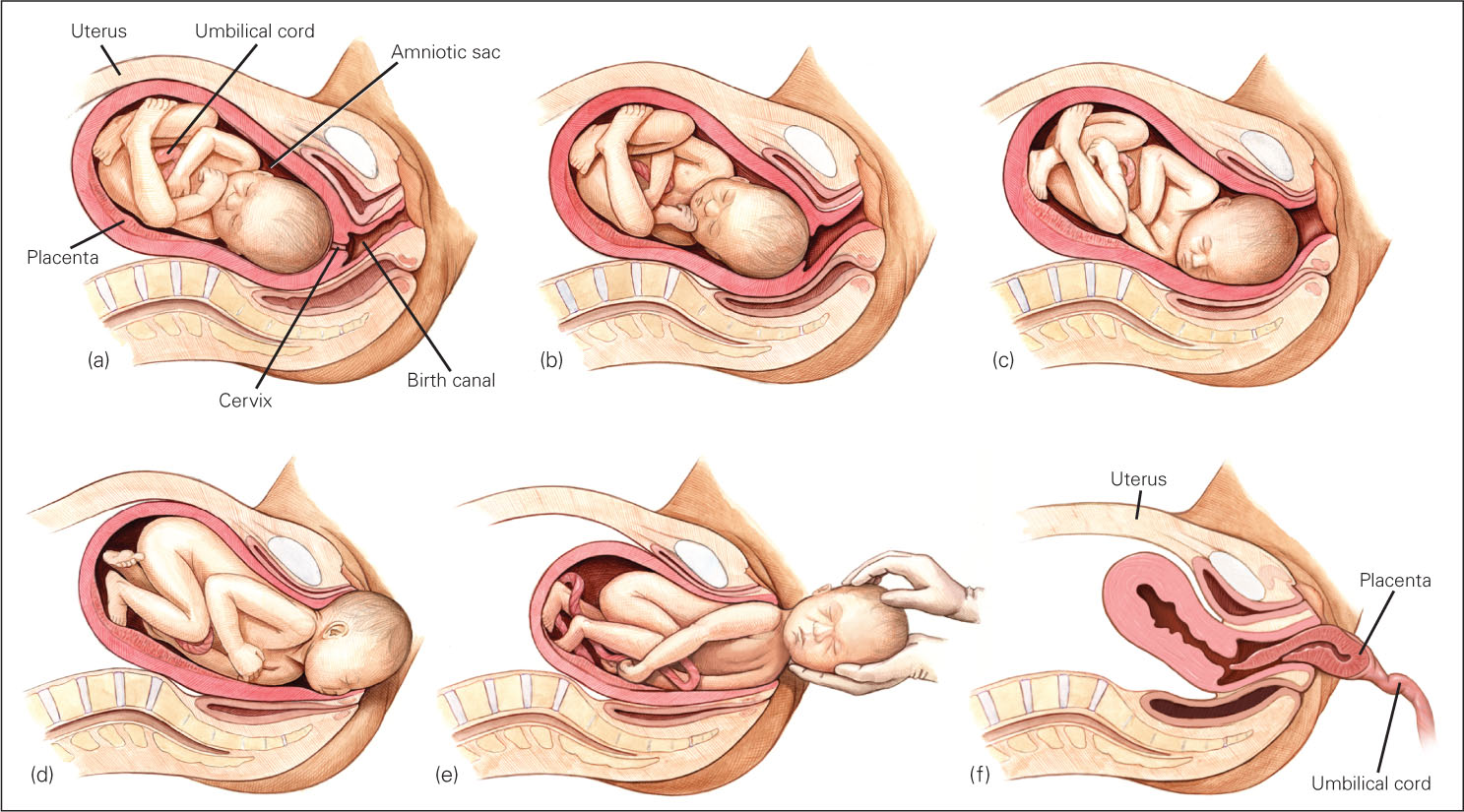

FIGURE 4.3

A Normal, Uncomplicated Birth (a) The baby’s position as the birth process begins. (b) The first stage of labor: The cervix dilates to allow passage of the baby’s head. (c) Transition: The baby’s head moves into the “birth canal,” the vagina. (d) The second stage of labor: The baby’s head moves through the opening of the vagina (the baby’s head “crowns”) and (e) emerges completely. (f) The third stage of labor is the expulsion of the placenta. This usually occurs naturally, but the entire placenta must be expelled, so birth attendants check carefully. In some cultures, the placenta is ceremonially buried, to commemorate its life-The Newborn’s First Minutes

Newborns usually breathe and cry on their own. Between spontaneous cries, the first breaths of air bring oxygen to the lungs and blood, and the infant’s color changes from bluish to pinkish. (Pinkish refers to blood color, visible beneath the skin, and applies to newborns of all hues.) Eyes open wide; tiny fingers grab; even tinier toes stretch and retract. The newborn is instantly, zestfully, ready for life.

Nevertheless, there is much to be done. If birth occurs with a Western-

Apgar scale A quick assessment of a newborn’s health. The baby’s color, heart rate, reflexes, muscle tone, and respiratory effort are given a score of 0, 1, or 2 twice—

One widely used assessment of infant health is the Apgar scale (see Table 4.3), first developed by Dr. Virginia Apgar. When she graduated from Columbia medical school with her M.D. in 1933, Apgar wanted to work in a hospital but was told that only men did surgery. Consequently, she became an anesthesiologist. She saw that “delivery room doctors focused on mothers and paid little attention to babies. Those who were small and struggling were often left to die” (Beck, 2009, p. D-

| Five Vital Signs | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | Color | Heartbeat | Reflex Irritability | Muscle Tone | Respiratory Effort | |||

| 0 | Blue, pale | Absent | No response | Flaccid, limp | Absent | |||

| 1 | Body pink, extremities blue | Slow (below 100) | Grimace | Weak, inactive | Irregular, slow | |||

| 2 | Entirely pink | Rapid (over 100) | Coughing, sneezing, crying | Strong, active | Good; baby is crying | |||

| Source: Apgar, 1953. | ||||||||

To save those young lives, Apgar developed a simple rating scale of five vital signs—

If the five-

Medical Assistance

How closely any particular birth matches the foregoing description depends on the parents’ preparation, the position and size of the fetus, and the customs of the culture. In developed nations, births almost always include sterile procedures, electronic monitoring, and drugs to dull pain or speed contractions.

Surgery

cesarean section (c-

Midwives are as skilled at delivering babies as physicians, but only medical doctors are licensed to perform surgery. More than one-

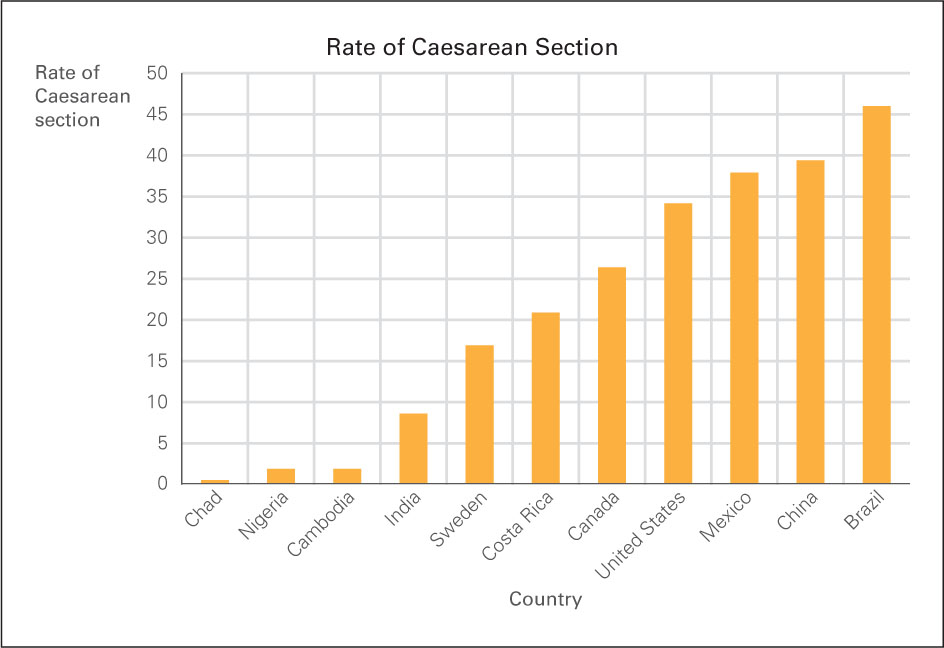

Most nations have fewer cesareans than the United States, but some—

FIGURE 4.4

Too Many Cesareans or Too Few? Rates of cesarean deliveries vary widely from nation to nation. Latin America has the highest rates in the world (note that 40 percent of all births in Chile are by cesarean), and sub-

In the United States, the rate rose every year between 1996 and 2008 (from 21 percent to 34 percent) before stabilizing. Variation is dramatic from one hospital to another—

Less studied is the epidural, an injection in a particular part of the spine of the laboring woman to alleviate pain. Epidurals are often used in hospital births, but they increase the rate of cesarean sections and decrease the readiness of newborn infants to suck immediately after birth (Bell et al., 2010). Another medical intervention is induced labor, in which labor is started, speeded up, or strengthened with a drug. The rate of induced labor in the United States tripled between 1990 and 2010, and is close to 20 percent. Starting labor before it begins spontaneously increases the incidence of cesarean birth (Jonsson et al., 2013).

Newborn Survival

A century ago, at least 5 of every 100 newborns in the United States died (De Lee, 1938), as did more than half of newborns in developing nations. In the least developed nations, the rate of newborn death may still be about 1 in 20, although some rural newborn deaths are not tallied. One estimate is that worldwide almost 2 million newborns (1 in 70) die each year (Rajaratnam et al., 2010).

Currently in the United States, newborn mortality is about 1 in 250—

Several aspects of birth arise from custom or politics, not from necessity (Stone & Selin, 2009). A particular issue in medically-

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends careful and honest counseling for parents of very preterm babies so that they understand the consequences of each medical measure. As an obstetrics team writes, “We should be frank with ourselves, with parents and with society, that there are gaps of knowledge concerning the management of infants born at very low gestational ages…including ethical decisions such as…when to provide intensive care and how extensive this should be” (Iacovidou et al., 2010, p. 133).

Alternatives to Hospital Technology

Especially for Conservatives and Liberals Do people’s attitudes about medical intervention at birth reflect their attitudes about medicine at other points in their life span, in such areas as assisted reproductive technology (ART), immunization, and life support?

Response for Conservatives and Liberals: Yes, some people are much more likely to want nature to take its course. However, personal experience often trumps political attitudes about birth and death; several of those who advocate hospital births are also in favor of spending one’s final days at home.

Questions of costs—

Most U.S. births now take place in hospital labor rooms with high-

Compared with the United States, planned home births are more common in many other developed nations (2 percent in England, 30 percent in the Netherlands) where midwives are paid by the government. In the Netherlands, special ambulances called flying storks speed mother and newborn to a hospital if needed. Dutch research finds home births better for mothers and no worse for infants than hospital births (de Jonge et al., 2013).

One crucial question is how supportive the medical professionals are. One committee of obstetricians decided that planned home births are acceptable because women have “a right to make a medically informed decision about delivery,” but they also insisted that a trained midwife or doctor be present, that the woman not be high-

doula A woman who helps with the birth process. Traditionally in Latin America, a doula was the only professional who attended childbirth. Now doulas are likely to arrive at the woman’s home during early labor and later work alongside a hospital’s staff.

Historically, women in hospitals labored by themselves until birth was imminent; fathers and other family members were kept away. Almost everyone now agrees that a laboring woman should never be alone. However, family members may not know how to help, and professionals focus more on the medical than the psychological aspects of birth. As a result, some women do not get adequate emotional support. Many women now have a doula, a woman trained to support the laboring woman, Doulas time contractions, use massage, provide encouragement, and do whatever else is helpful.

Often doulas begin their work before active labor begins. When the actual birth is imminent, they work beside the midwives or doctors. Many studies have found that doulas benefit low-

SUMMING UP

Most newborns weigh about 7½ pounds (3.4 kilograms), score at least 7 out of 10 on the Apgar scale, and thrive without medical assistance. If necessary, neonatal surgery and intensive care save lives. Although modern medicine has reduced maternal and newborn deaths, many critics deplore treating birth as a medical crisis rather than a natural event. Responses to this critique include women choosing to give birth in hospital labor rooms rather than operating rooms, in birthing centers instead of hospitals, or even at home. The assistance of a doula is another recent practice that reduces medical intervention.