Problems and Solutions

Problems and Solutions

The early days of life place the developing newborn on the path toward health and success—

Harmful Substances

teratogen An agent or condition, including viruses, drugs, and chemicals, that can impair prenatal development and result in birth defects or even death.

Such a cascade begins before the woman realizes she is pregnant, as many toxins, illnesses, and experiences can cause harm early in pregnancy. Every week, scientists discover an unexpected teratogen, which is anything—

behavioral teratogens Agents and conditions that can harm the prenatal brain, impairing the future child’s intellectual and emotional functioning.

Some teratogens cause no physical defects but affect the brain, making a child hyperactive, antisocial, or learning-

I was nine years old when my mother announced she was pregnant. I was the one who was most excited…. My mother was a heavy smoker, Colt 45 beer drinker and a strong caffeine coffee drinker.

One day my mother was sitting at the dining room table smoking cigarettes one after the other. I asked “Isn’t smoking bad for the baby? She made a face and said “Yes, so what?” I said “So why are you doing it?” She said, “I don’t know.”…

During this time I was in the fifth grade and we saw a film about birth defects. My biggest fear was that my mother was going to give birth to a fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) infant…. My baby brother was born right on schedule. The doctors claimed a healthy newborn…. Once I heard healthy, I thought everything was going to be fine. I was wrong, then again I was just a child…. My baby brother never showed any interest in toys…he just cannot get the right words out of his mouth…he has no common sense…

Why hurt those who cannot defend themselves?

[J., personal communication]

Especially for Judges and Juries How much protection, if any, should the legal system provide for fetuses? Should alcoholic women who are pregnant be jailed to prevent them from drinking? What about people who enable them to drink, such as their partners, their parents, bar owners, and bartenders?

Response for Judges and Juries: Some laws punish women who jeopardize the health of their fetuses, but a developmental view would consider the micro-

As you remember from Chapter 1, one case proves nothing. J. blames her mother, although genes, postnatal experiences, and lack of preventive information and services may be part of the cascade as well. Nonetheless, J. rightly wonders why her mother took a chance.

Behavioral teratogens can be subtle, yet their effects may last a lifetime. That is one conclusion from research on the babies born to pregnant women exposed to flu in 1918. By middle age, although some of these babies grew up to be rich and brilliant, on average those born in flu-

Risk Analysis

Life requires risks: We analyze which chances to take and how to minimize harm. To pick an easy example: Crossing the street is risky, yet it would be worse to avoid all street crossing. Knowing the danger, we cross carefully, looking both ways.

Sixty years ago no one analyzed the risks of prenatal development. It was assumed that the placenta screened out all harmful substances. Then two tragic episodes showed otherwise. First, on an Australian military base, an increase in the number of babies born blind was linked to a rubella (German measles) epidemic on the same base seven months earlier (Gregg, 1941; reprinted in Persaud et al., 1985). Second, a sudden rise in British newborns with deformed limbs was traced to maternal use of thalidomide, a new drug for nausea that was widely prescribed in Europe in the late 1950s (Schardein, 1976).

Thus began teratology, a science of risk analysis. Although all teratogens increase the risk of harm, none always cause damage. The impact of teratogens depends on the interplay of many factors, both destructive and protective, an example of the dynamic-

The Critical Time

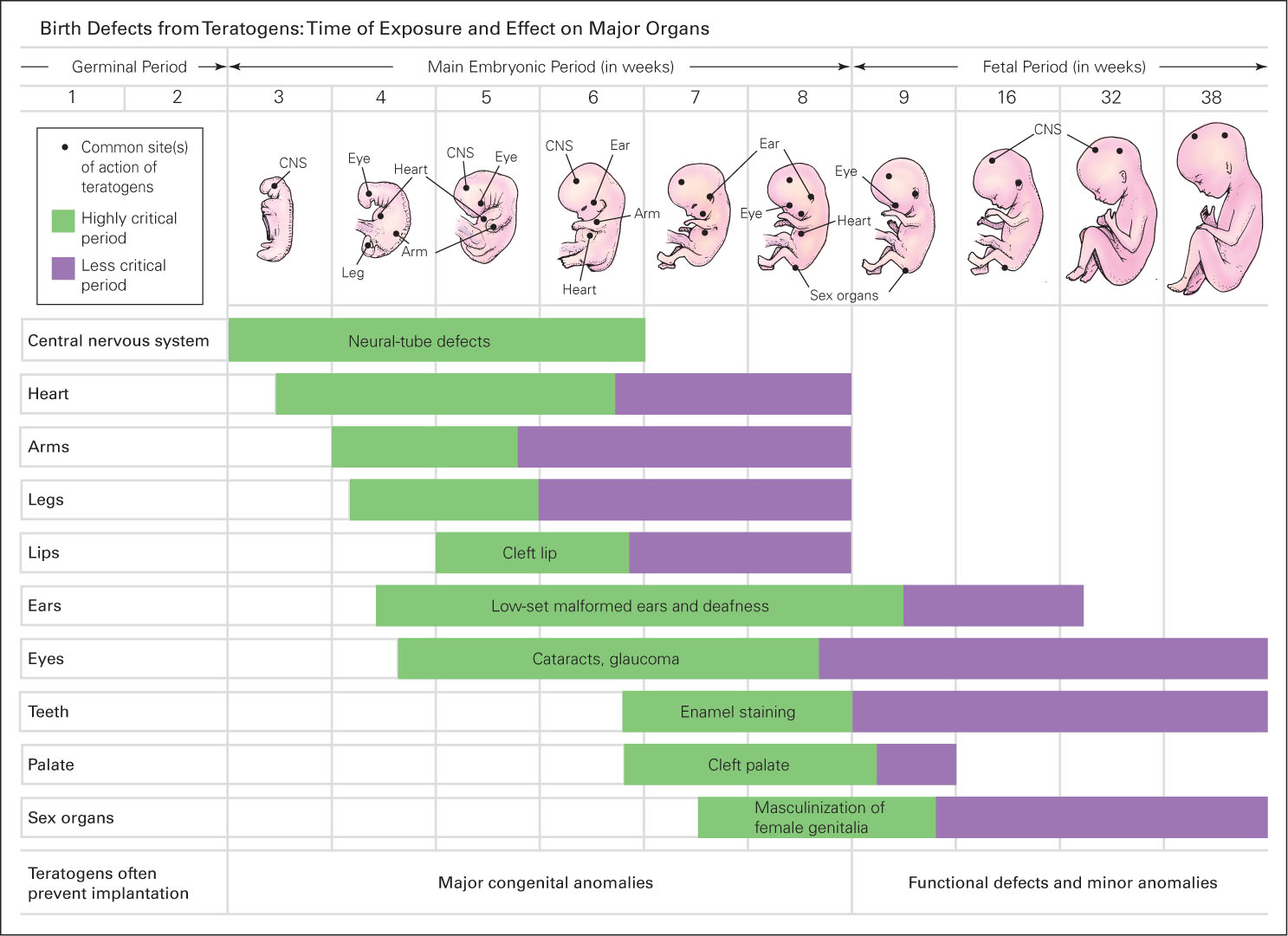

Timing is crucial. Some teratogens cause damage only during a critical period (see Figure 4.5). [Lifespan Link: Critical and sensitive periods are described in Chapter 1.] Obstetricians recommend that before pregnancy occurs, women should avoid drugs (especially alcohol), supplement a balanced diet with extra folic acid and iron, and update their immunizations. Indeed, preconception health is at least as important as postconception health (see Table 4.4).

FIGURE 4.5

Critical Periods in Human Development The most serious damage from teratogens (green bars) is likely to occur early in prenatal development. However, significant damage (purple bars) to many vital parts of the body, including the brain, eyes, and genitals, can occur during the last months of pregnancy as well.| What Prospective Mothers Should Do | What Prospective Mothers Really Do (U.S. Data) |

|---|---|

| 1. Plan the pregnancy. | 1. At least a third of all pregnancies are not intended. |

| 2. Take a daily multivitamin with folic acid. | 2. About 60 percent of women aged 18 to 45 do not take multivitamins. |

| 3. Avoid binge- |

3. One in seven women in their childbearing years binge- |

| 4. Update immunizations against all teratogenic viruses, especially rubella. | 4. Unlike in many developing nations, relatively few pregnant women in the United States lack basic immunizations. |

| 5. Gain or lose weight, as appropriate. | 5. About one- |

| 6. Reassess use of prescription drugs. | 6. Ninety percent of pregnant women take prescription drugs (not counting vitamins). |

| 7. Develop daily exercise habits. | 7. More than half of women of childbearing age do not exercise. |

| Sources: Bombard et al., 2013; MMWR, (July 20, 2012); Mitchell et al., 2012; Mosher et al, 2012; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012. | |

The first days and weeks after conception (the germinal and embryonic periods) are critical for body formation, but health during the entire fetal period affects the brain. Some teratogens that cause preterm birth or low birthweight are particularly harmful in the second half of pregnancy. In fact, one study found that although smoking cigarettes throughout prenatal development can harm the fetus, smokers who quit early in pregnancy had no higher risks of birth complications than did women who never smoked (McCowan et al., 2009).

Timing may be important in another way. When pregnancy occurs soon after a previous pregnancy, risk increases. For example, one study found that second-

How Much Is Too Much?

threshold effect In prenatal development, when a teratogen is relatively harmless in small doses but becomes harmful once exposure reaches a certain level (the threshold).

A second factor affecting the harm from teratogens is the dose and/or frequency of exposure. Some teratogens have a threshold effect; they are virtually harmless until exposure reaches a certain level, at which point they “cross the threshold” and become damaging. This threshold is not a fixed boundary: Dose, timing, frequency, and other teratogens affect when the threshold is crossed (O’Leary et al., 2010).

A few substances are beneficial in small amounts but fiercely teratogenic in large quantities. One such substance is vitamin A, which is essential for healthy development but a cause of abnormalities if the dose is 50,000 units per day or higher (obtained only in pills) (Naudé et al., 2007). Experts rarely specify thresholds for any drug, partly because one teratogen may reduce the threshold of another. Alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana are more teratogenic when all three are combined.

fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) A cluster of birth defects, including abnormal facial characteristics, slow physical growth, and reduced intellectual ability, that may occur in the fetus of a woman who drinks alcohol while pregnant.

Is there a safe amount of psychoactive drugs? Consider alcohol. Early in pregnancy, an embryo exposed to heavy drinking can develop fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), which distorts the facial features (especially the eyes, ears, and upper lip). Later in pregnancy, alcohol is a behavioral teratogen, leading to hyperactivity, poor concentration, impaired spatial reasoning, and slow learning (Niccols, 2007; Riley et al., 2011).

Some pregnant women, however, drink some alcohol with no evident harm to the fetus. If drinking during pregnancy always caused harm, almost everyone born in Europe before 1980 would be affected. Currently, pregnant women are advised to avoid all alcohol, but women in the United Kingdom receive conflicting advice about drinking a glass of wine a day or two a week (Raymond et al., 2009), and French women are told to abstain but many do not heed that message (Toutain, 2010). Should all women who might become pregnant avoid a legal substance that most men use routinely? Wise? Probably. Necessary?

Innate Vulnerability

Genes are a third factor that influences the effects of teratogens. When a woman carrying dizygotic twins drinks alcohol, for example, the twins’ blood alcohol levels are equal; yet one twin may be more severely affected than the other because their alleles for the enzyme that metabolizes alcohol differ. Genetic vulnerability is suspected for many birth defects (Sadler et al., 2010).

The Y chromosome may be crucial in some differential sensitivity. Male fetuses are more likely to be spontaneously aborted or stillborn and also more likely to be harmed by teratogens than female fetuses.

Especially for Nutritionists Is it beneficial that most breakfast cereals are fortified with vitamins and minerals?

Response for Nutritionists: Useful, yes; optimal, no. Some essential vitamins are missing (too expensive), and individual nutritional needs differ, depending on age, sex, health, genes, and eating habits. The reduction in neural-

Genes may be important not only at conception but also during pregnancy. One maternal allele results in low levels of folic acid in a woman’s bloodstream and hence in the embryo, which can produce neural-

Since 1998 in the United States, every packaged cereal has added folic acid, an intervention that reduced neural-

Applying the Research

Risk analysis cannot precisely predict the results of teratogenic exposure in individual cases. However, much is known more generally about destructive and damaging teratogens and what can be done by individuals and society to reduce the risks. Table 4.5 lists some teratogens and their possible effects, as well as preventive measures.

| Teratogens | Effects of Exposure on Fetus | Measures for Preventing Damage (Laws, doctors, and individuals can all increase prevention) |

|---|---|---|

| Diseases | ||

| Rubella (German measles) | In embryonic period, causes blindness and deafness; in first and second trimesters, causes brain damage. | Immunization before becoming pregnant. |

| Toxoplasmosis | Brain damage, loss of vision, intellectual disabilities. | Avoid eating undercooked meat and handling cat feces, garden dirt during pregnancy. |

| Measles, chicken pox, influenza | May impair brain functioning. | Immunization of all children and adults. |

| Syphilis | Baby is born with syphilis, which, untreated, leads to brain and bone damage and eventual death. | Early prenatal diagnosis and treatment with antibiotics. |

| HIV | Baby may catch the virus. Without treatment, illness and death are likely during childhood. | Prenatal drugs and cesarean birth make HIV transmission rare. |

| Other sexually transmitted infections, including gonorrhea and chlamydia | Not usually harmful during pregnancy but may cause blindness and infections if transmitted during birth. | Early diagnosis and treatment; if necessary, cesarean section, treatment of newborn. |

| Infections, including infections of urinary tract, gums, and teeth | May cause premature labor, which increases vulnerability to brain damage. | Good, inexpensive medical care before pregnancy. |

| Pollutants | ||

| Lead, mercury, PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls); dioxin; and some pesticides, herbicides, and cleaning compounds | May cause spontaneous abortion, preterm labor, and brain damage. | May be harmless in small doses, but pregnant women should avoid exposure, such as drinking well water, eating unwashed fruits or vegetables, using chemicals, eating fish from polluted waters. |

| Radiation | ||

| Massive or repeated exposure to radiation, as in medical X- |

May cause small brains (microcephaly) and intellectual disabilities. Background radiation probably harmless. | Sonograms, not X- |

| Social and Behavioral Factors | ||

| Very high stress | May cause cleft lip or cleft palate, spontaneous abortion, or preterm labor. | Adequate relaxation, rest, and sleep; reduce intensity of employment, housework and child care. |

| Malnutrition | When severe, interferes with conception, implantation, normal fetal development. | Eat a balanced diet, normal weight before pregnancy, gain 25– |

| Excessive, exhausting exercise | Can harm fetal growth if it interferes with woman’s sleep, digestion, or nutrition. | Regular, moderate exercise is best for everyone. |

| Medicinal Drugs | ||

| Lithium | Can cause heart abnormalities. | Avoid all medicines, whether prescription or over the counter, during pregnancy unless given by a medical professional who knows recent research on teratogens. |

| Tetracycline | Can harm teeth. | |

| Retinoic acid | Can cause limb deformities. | |

| Streptomycin | Can cause deafness. | |

| ACE inhibitors | Can harm digestive organs. | |

| Phenobarbital | Can affect brain development. | |

| Thalidomide | Can stop ear and limb formation. | |

| Psychoactive Drugs | ||

| Caffeine | Normal, modest use poses no problem. | Avoid excessive use. (Note that coffee, tea, cola drinks, chocolate all contain caffeine). |

| Alcohol | May cause fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) or fetal alcohol effects (FAE). | Stop or severely limit alcohol consumption; especially dangerous are three or more drinks a day or four or more drinks on one occasion. |

| Tobacco | Reduces birthweight, increases risk of malformations of limbs and urinary tract, and may affect the baby’s lungs. | Ideally, stop smoking before pregnancy. Stopping during pregnancy also beneficial. |

| Marijuana | Heavy exposure affects central nervous system; when smoked, may hinder fetal growth. | Avoid or strictly limit marijuana consumption. |

| Heroin | Slows fetal growth, increases prematurity. Addicted newborns need treatment to control withdrawal. | Treatment needed before pregnancy but if already pregnant, gradual withdrawal on methadone is better than continued use of heroin. |

| Cocaine | Slows fetal growth, increases prematurity and then learning problems. | Stop before pregnancy; if not, babies need special medical and educational attention in their early years. |

| Inhaled solvents (glue or aerosol) | May cause abnormally small head, crossed eyes, and other indications of brain damage. | Stop before becoming pregnant; damage can occur before a woman knows she is pregnant. |

| * The field of toxicology advances daily. Research on new substances begins with their effects on nonhuman species, which provides suggestive (though not conclusive) evidence. This table is a primer; it is no substitute for careful consultation with a knowledgeable professional. | ||

General health during pregnancy matters. Women are advised to maintain good nutrition and especially to avoid drugs and teratogenic chemicals (which are often found in pesticides, cleaning fluids, and cosmetics). Some medications are necessary (e.g., for women with epilepsy, diabetes, and severe depression), but caution and consultation should begin before pregnancy is confirmed.

Sadly, the cascade of teratogens is most likely to begin with women who are already vulnerable. For example, cigarette smokers are more often drinkers (as was J.’s mother); and those whose jobs require exposure to chemicals and pesticides are more often malnourished (Ahmed & Jaakkola, 2007; Hougaard & Hansen, 2007).

Advice from Doctors

Although prenatal care is helpful in protecting the developing fetus, even doctors are not always careful. One study of 152,000 new mothers in eight U.S. health maintenance organizations (HMOs) found that, during pregnancy, 40 percent of the women were given prescriptions for drugs that had not been declared safe during pregnancy, and 2 percent were prescribed drugs with proven risks to fetuses (Andrade et al., 2004). Perhaps these physicians did not know their patients were pregnant, but even a few of the wrong pills early in pregnancy may do harm.

Worse still is the failure of some doctors to advise women about harmful life patterns. For example, one Maryland study found that almost one-

Advice from Scientists

Scientists interpret research in contradictory ways. For instance, pregnant women in the United States are told to eat less fish, but those in the United Kingdom are told to increase fish consumption. The reason for these opposite messages is that fish contains both mercury (a teratogen) and DHA (an omega-

Another dispute involves bisphenol A (commonly used in plastics), banned in Canada but allowed in the United States. The effect of bisphenol A is disputed because research on mice, not humans, finds it teratogenic. Should people be guided by mouse studies?

Undisputed epidemiological research on humans is logistically difficult because exposure must be measured at several different time points, including early gestation, but the outcome may not manifest itself for many years. No doubt pregnant women are more exposed to bisphenol A than they were a decade ago, and exposure correlates with hyperactive 2-

It is certain that prenatal teratogens can cause behavioral problems, reproductive impairment, and several diseases. Almost every common disease, almost every food additive, most prescription and nonprescription drugs (even caffeine and aspirin), many minerals in the air and water, emotional stress, exhaustion, and poor nutrition might impair prenatal development—

Especially for Social Workers When is it most important to convince women to be tested for HIV: before pregnancy, after conception, or immediately after birth?

Response for Social Workers: Testing and then treatment are useful at any time because women who know they are HIV-

Most research is conducted with mice; harm to humans is rarely proven to everyone’s satisfaction. Even when evidence seems clear, the proper social response is controversial. If a pregnant woman uses alcohol or other psychoactive drugs, should she be jailed for abusing her fetus, as is legal in five U.S. states (Minnesota, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, and Wisconsin)? If a baby is stillborn, should the mother be convicted of murder, as occurred for an Oklahoma woman, Theresa Hernandez, who took meth while pregnant and was sentenced to 15 years? (Fentiman, 2009)

Prenatal Diagnosis

Early prenatal care has many benefits: Women learn what to eat, what to do, and what to avoid. Some serious conditions, syphilis and HIV among them, can be diagnosed and treated before any harm to the fetus occurs. In addition, prenatal tests (of blood, urine, and fetal heart rate as well as ultrasound) reassure parents, facilitating the crucial parent-

In general, early care protects fetal growth, makes birth easier, and renders parents better able to cope. When complications (such as twins, gestational diabetes, and infections) arise, early recognition increases the chance of a healthy birth.

false positive The result of a laboratory test that reports something as true when in fact it is not true. This can occur for pregnancy tests, when a woman might not be pregnant even though the test says she is, or during pregnancy when a problem is reported that actually does not exist.

Unfortunately, however, about 20 percent of early pregnancy tests raise anxiety instead of reducing it. For instance, the level of alpha-

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

“What Do People Live to Do?”

John and Martha, both under age 35, were expecting their second child. Martha’s initial prenatal screening revealed low alpha-

Another blood test was scheduled…. John asked:

“What exactly is the problem?”…

“We’ve got a one in eight hundred and ninety-

John smiled, “I can live with those odds.”

“I’m still a little scared.”

He reached across the table for my hand. “Sure,” he said, “that’s understandable. But even if there is a problem, we’ve caught it in time…. The worst-

“I might have to have an abortion?” The chill inside me was gone. Instead I could feel my face flushing hot with anger. “Since when do you decide what I have to do with my body?”

John looked surprised. “I never said I was going to decide anything,” he protested. “It’s just that if the tests show something wrong with the baby, of course we’ll abort. We’ve talked about this.”

“What we’ve talked about,” I told John in a low, dangerous voice, “is that I am pro-

“You used to be,” said John.

“I know I used to be.” I rubbed my eyes. I felt terribly confused. “But now…look, John, it’s not as though we’re deciding whether or not to have a baby. We’re deciding what kind of baby we’re willing to accept. If it’s perfect in every way, we keep it. If it doesn’t fit the right specifications, whoosh! Out it goes.”…

John was looking more and more confused. “Martha, why are you on this soapbox? What’s your point?”

“My point is,” I said, “that I’m trying to get you to tell me what you think constitutes a ‘defective’ baby. What about…oh, I don’t know, a hyperactive baby? Or an ugly one?”

“They can’t test for those things and—

“Well, what if they could?” I said. “Medicine can do all kinds of magical tricks these days. Pretty soon we’re going to be aborting babies because they have the gene for alcoholism, or homosexuality, or manic depression…. Did you know that in China they abort a lot of fetuses just because they’re female?” I growled. “Is being a girl ‘defective’ enough for you? “

“Look,” he said, “I know I can’t always see things from your perspective. And I’m sorry about that. But the way I see it, if a baby is going to be deformed or something, abortion is a way to keep everyone from suffering—especially the baby. It’s like shooting a horse that’s broken its leg…. A lame horse dies slowly, you know?…It dies in terrible pain. And it can’t run anymore. So it can’t enjoy life even if it doesn’t die. Horses live to run; that’s what they do. If a baby is born not being able to do what other people do, I think it’s better not to prolong its suffering.”

“…And what is it,” I said softly, more to myself than to John, “what is it that people do? What do we live to do, the way a horse lives to run?”

[Beck, 1999, pp. 132–

The second AFP test was in the normal range, “meaning there was no reason to fear…Down syndrome” (p. 137).

As you read in Chapter 3, genetic counselors help couples discuss their choices before becoming pregnant. John and Martha had had no counseling because the pregnancy was unplanned and their risk for Down syndrome was low. The opposite of a false positive is a false negative, a mistaken assurance that all is well. Amniocentesis later revealed that the second AFP was a false negative. Their fetus had Down syndrome after all. Martha decided against abortion.

Low Birthweight

Some newborns are small and immature. With modern hospital care, tiny infants usually survive, but it would be better for everyone—

low birthweight (LBW) A body weight at birth of less than 5½ pounds (2,500 grams).

very low birthweight (VLBW) A body weight at birth of less than 3 pounds, 5 ounces (1,500 grams).

extremely low birthweight (ELBW) A body weight at birth of less than 2 pounds, 3 ounces (1,000 grams).

The World Health Organization defines low birthweight (LBW) as under 2,500 grams. LBW babies are further grouped into very low birthweight (VLBW), under 1,500 grams (3 pounds, 5 ounces), and extremely low birthweight (ELBW), under 1,000 grams (2 pounds, 3 ounces). Some newborns weigh as little as 500 grams, and they are the most vulnerable—

Maternal Behavior and Low Birthweight

preterm A birth that occurs 3 or more weeks before the full 38 weeks of the typical pregnancy—

Remember that fetal weight normally doubles in the last trimester of pregnancy, with 900 grams (about 2 pounds) of that gain occurring in the final three weeks. Thus, a baby born preterm (three or more weeks early; no longer called premature) is usually, but not always, LBW. Preterm birth correlates with many of the teratogens already mentioned, part of the cascade.

small for gestational age (SGA) A term for a baby whose birthweight is significantly lower than expected, given the time since conception. For example, a 5-

Not every low-

Another common reason for slow fetal growth is malnutrition. Women who begin pregnancy underweight, who eat poorly during pregnancy, or who gain less than 3 pounds (1.3 kilograms) per month in the last six months more often have underweight infants.

Unfortunately, many risk factors—

What About the Father?

The causes of low birthweight just mentioned rightly focus on the pregnant woman. However, fathers—

As already explained in Chapter 1, each person is embedded in a social network. Since the future mother’s behavior impacts the fetus, everyone who affects her also affects the fetus. For instance, unintended pregnancies increase the incidence of low birthweight (Shah et al., 2011). Obviously, intentions are in the mother’s mind, not her body, and they are affected by the father. Thus, the father’s intentions affect her diet, drug use, prenatal care, and so on.

Not only fathers but also the entire social network and culture are crucial (Lewallen, 2011). This is most apparent in what is called the immigrant paradox. Many immigrants have difficulty getting well-

This paradox was first recognized among Hispanics, who are the main immigrant group in the U.S., and it was called the Hispanic paradox. Thus, although U.S. residents born in Mexico or South America average lower SES than Hispanics born in the United States, their newborns have fewer problems. Why? Perhaps fathers and grandparents keep pregnant immigrant women drug-

Consequences of Low Birthweight

You have already read that life itself is uncertain for the smallest newborns. Ranking worse than most developed nations—

Moreover, the death rate of the tiniest babies seems to be rising, not falling, even as fewer slightly older newborns die, which is why U.S. infant mortality rates are not falling as fast as they are in other nations (Lau et al., 2013). For survivors who are born very low birthweight, every developmental milestone—

Low-

Longitudinal research from many nations finds that, in middle childhood, children who were at the extremes of SGA or preterm have many neurological problems, including smaller brain volume, lower IQs, and behavioral difficulties (Hutchinson et al., 2013; van Soelen et al., 2010). Even in adulthood, risks persist: Adults who were LBW are more likely to develop diabetes and heart disease.

Longitudinal data provide both hope and caution. Remember that risk analysis gives odds, not certainties—

Comparing Nations

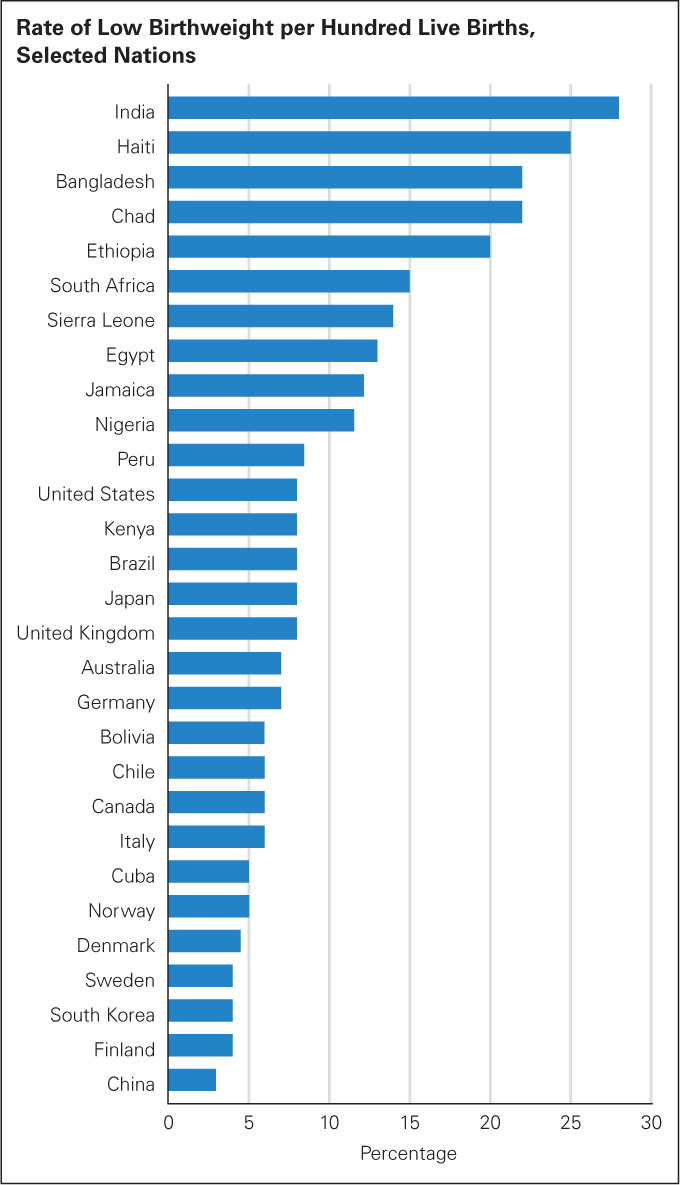

In some northern European nations, only 4 percent of newborns weigh under 2,500 grams; in several South Asian nations, more than 20 percent do. Worldwide, far fewer low-

Some nations, China and Chile among them, have improved markedly. In 1970, about half of Chinese newborns were LBW; recent estimates put that number at 4 percent (UNICEF, 2010). In some nations, community health programs aid the growth of low-

FIGURE 4.6

Getting Better Some public health experts consider the rate of low birthweight to be indicative of national health, since both are affected by the same causes. If that is true, the world is getting healthier, since the LBW world average was 28 percent in 2009 but 16 percent in 2012. When all nations are included, 47 report LBW at 6 per 100 or lower (United States and United Kingdom are not among them).In some nations, notably in sub-

Many scientists have developed hypotheses to explain the U.S. rates. One logical possibility is assisted reproduction, since ART often leads to low-

For example, African Americans have LBW newborns twice as often as the national average (almost 14 percent compared with 7 percent), and younger teenagers have smaller babies than do women in their 20s. However, the birth rate among both groups was much lower in 2010 than it was in 1990. Furthermore, maternal obesity and diabetes are increasing; both lead to heavier babies, not lighter ones.

Something else must be amiss. One possibility is nutrition. Nations with many small newborns are also nations where hunger is prevalent, and increasing hunger correlates with increasing LBW. In both Chile and China, LBW fell as nutrition improved.

As for the United States, the U.S. Department of Agriculture found an increase in food insecurity (measured by skipped meals, use of food stamps, and outright hunger) between 2000 and 2007. Food insecurity directly affects LBW, and it also increases chronic illness, which itself correlates with LBW (Seligman & Schillinger, 2010).

In 2008, about 15 percent of U.S. households were considered food insecure, with rates higher among women in their prime reproductive years than among middle-

Another possibility is drug use. As you will see in Chapter 16, the rate of smoking, drinking, and other drug use among high school girls reached a low in 1992, then increased, then decreased. Most U.S. women giving birth in the first decade of the 20th century are in a cohort that experienced rising drug use; they may still suffer the effects. If that is the reason, the recent decrease in drug use among teenagers will result in fewer LBW in the second decade of the 21st century. Sadly, in developing nations, more young women are smoking and drinking than a decade ago, including in China. Will rates rise in China soon?

A third possibility is pollution. Air pollution is increasing in China, but decreasing in the United States. If pollution is the cause, low birth rate in those nations may change in the next decade. Looking at trends in various nations will help developmentalists understand how to prevent LBW in the future.

Complications During Birth

cerebral palsy A disorder that results from damage to the brain’s motor centers. People with cerebral palsy have difficulty with muscle control, so their speech and/or body movements are impaired.

Any birth complication usually has multiple causes: a fetus is low birthweight, preterm, or exposed to teratogens and a mother is unusually young, old, small, or ill. As an example, cerebral palsy (a disease marked by difficulties with movement) was once thought to be caused solely by birth procedures (excessive medication, slow breech birth, or use of forceps to pull the fetal head through the birth canal). However, we now know that cerebral palsy results from genetic vulnerability, teratogens, and maternal infection (J. R. Mann et al., 2009), worsened by insufficient oxygen to the fetal brain at birth.

anoxia A lack of oxygen that, if prolonged, can cause brain damage or death.

A lack of oxygen is anoxia. Anoxia often occurs for a second or two during birth, indicated by a slower fetal heart rate, with no harm done. To prevent prolonged anoxia, the fetal heart rate is monitored during labor and the Apgar is used immediately after birth. How long anoxia can continue without harming the brain depends on genes, birthweight, gestational age, drugs in the bloodstream (either taken by the mother before birth or given during birth), and many other factors. Thus, anoxia is part of a cascade that may cause cerebral palsy. The same cascade applies to almost every other birth complication.

SUMMING UP

Risk analysis is complex but necessary to protect every fetus. Many factors reduce risk, including the mother’s health and nourishment before pregnancy, her early prenatal care and drug use, and the father’s support. The timing of exposure to teratogens, the amount of toxin ingested, and the genes of the mother and fetus may be crucial. Low birthweight, slow growth, and preterm birth increase vulnerability. The birth process itself can worsen the effects of any vulnerability, especially if anoxia lasts more than a moment or two.