Growth in Infancy

Growth in Infancy

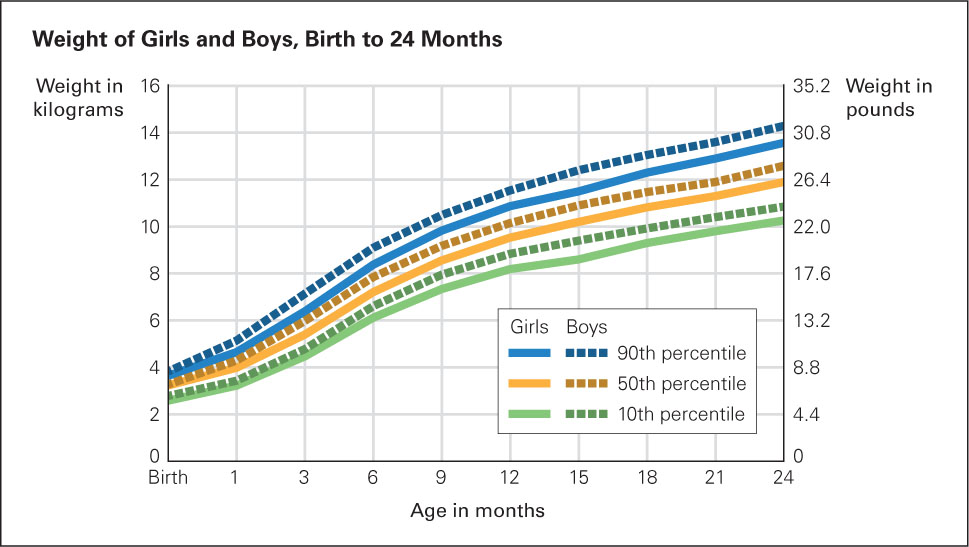

In infancy, growth is so rapid and the consequences of neglect are so severe that gains are closely monitored. Medical checkups, including measurement of height, weight, and head circumference, occur often in developed nations because these measurements provide the first clues as to whether an infant is progressing as expected—

Body Size

Newborns lose several ounces in the first three days and then gain an ounce a day for months. Birthweight typically doubles by 4 months and triples by a year. An average 7-

Physical growth then slows, but not by much. Most 24-

FIGURE 5.1

Eat and Sleep The rate of increasing weight in the first weeks of life makes it obvious why new babies need to be fed day and night.Each of these numbers is a norm, which is an average, or standard, for a particular population. The “particular population” for the norms just cited is United States infants in about 1970.

percentile A point on a ranking scale of 0 to 100. The 50th percentile is the midpoint; half the people in the population being studied rank higher and half rank lower.

At each well-

For a baby who has always been average (50th percentile), something is amiss if the percentile changes a lot, either up or down. If an average baby suddenly grows more slowly, that could be the first sign of a medical condition called failure to thrive. If weight gain is much above the norm, that may be a warning for later obesity.

Abnormal growth in either direction was once blamed on parents. For small babies, it was thought that parents made feeding stressful, leading to “nonorganic failure to thrive.” Now dozens of medical conditions have been discovered that cause failure to thrive. Pediatricians consider it “outmoded” to blame parents (Jaffe, 2011, p. 100).

Brain Growth

head-

Prenatal and postnatal brain growth (measured by head circumference) affects later cognition (Gilles & Nelson, 2012). If teething or a stuffed-

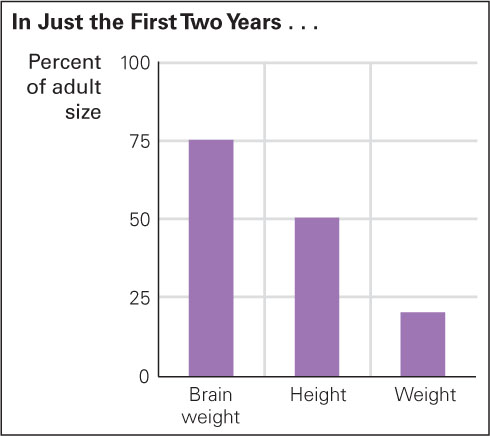

From two weeks after conception to two years after birth, the brain grows more rapidly than any other organ, being about 25 percent of adult weight at birth and almost 75 percent at age 2 (see Figure 5.2). Over the same period, head circumference increases from about 14 to 19 inches.

FIGURE 5.2

Growing Up Two-The brain develops lifelong; it is mentioned in every chapter of this book. We begin with the basics—

Neurons Connecting

neuron One of billions of nerve cells in the central nervous system, especially in the brain.

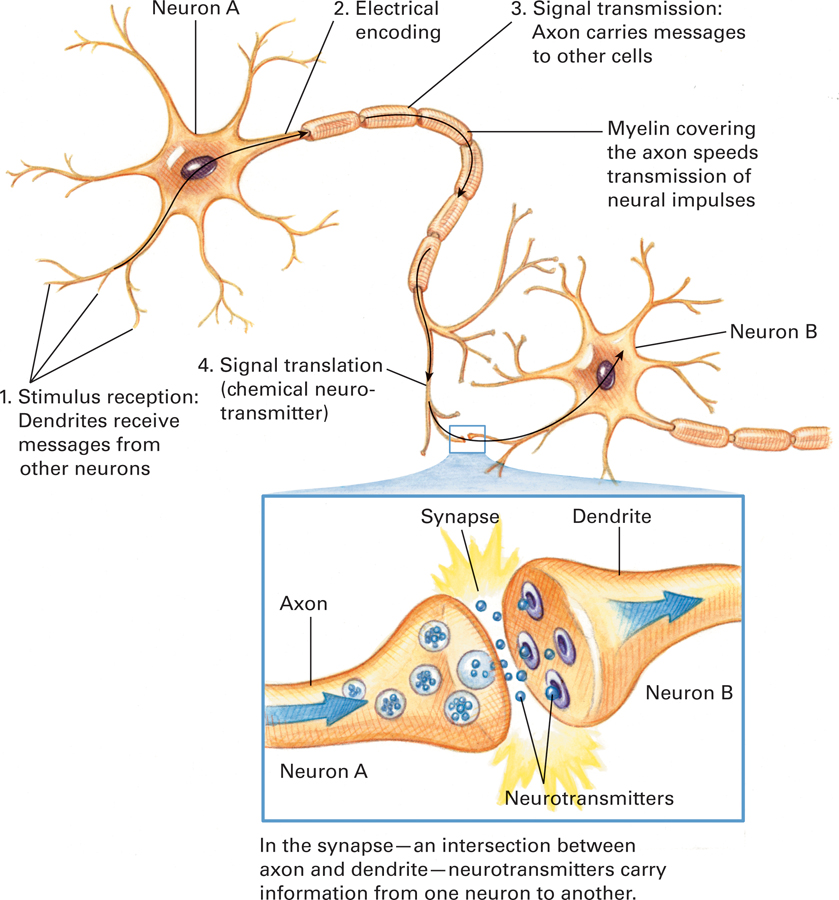

Communication within the central nervous system (CNS)—the brain and spinal cord—

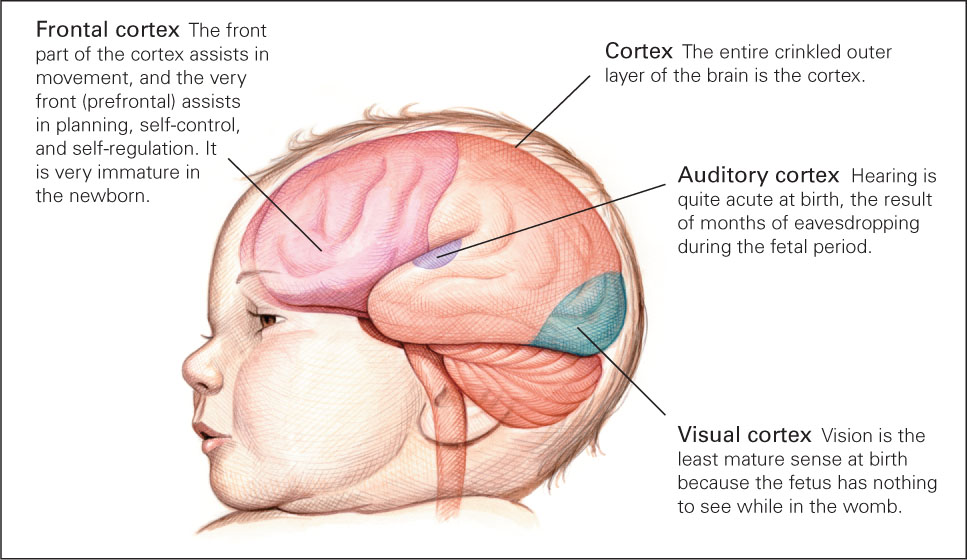

cortex The outer layers of the brain in humans and other mammals. Most thinking, feeling, and sensing involves the cortex.

The newborn brain has billions of neurons, about 70 percent of them in the cortex, the brain’s six outer layers (see Figure 5.3). Most thinking, feeling, and sensing occur in the cortex (Johnson, 2010).

FIGURE 5.3

The Developing Cortex The infant’s cortex consists of four to six thin layers of tissue that cover the rest of the brain. The cortex contains virtually all the neurons that make conscious thought possible. Some areas, such as those devoted to the senses, mature relatively early. Others, such as the prefrontal cortex, mature quite late.prefrontal cortex The area of the cortex at the very front of the brain that specializes in anticipation, planning, and impulse control.

The final part of the brain to mature is the prefrontal cortex, the area for anticipation, planning, and impulse control. It is not, as once thought, “functionally silent during most of infancy” (Grossmann, 2013, p. 303). Nonetheless, many of the connections between emotions and thought have not yet formed. The prefrontal cortex gradually becomes more efficient over the next two decades (Wahlstrom et al., 2010). [Lifespan Link: Major discussion of the growth of the prefrontal cortex is in Chapter 14.]

All areas of the brain specialize, becoming fully functioning at different ages. Some regions deep within the skull maintain breathing and heartbeat, and thus are able to sustain life by seven months after conception. Some areas in the mid-

Examples of this specialization are the areas of the cortex: a visual cortex, an auditory cortex, and an area dedicated to the sense of touch for each body part—

axon A fiber that extends from a neuron and transmits electrochemical impulses from that neuron to the dendrites of other neurons.

dendrite A fiber that extends from a neuron and receives electrochemical impulses transmitted from other neurons via their axons.

synapse The intersection between the axon of one neuron and the dendrites of other neurons.

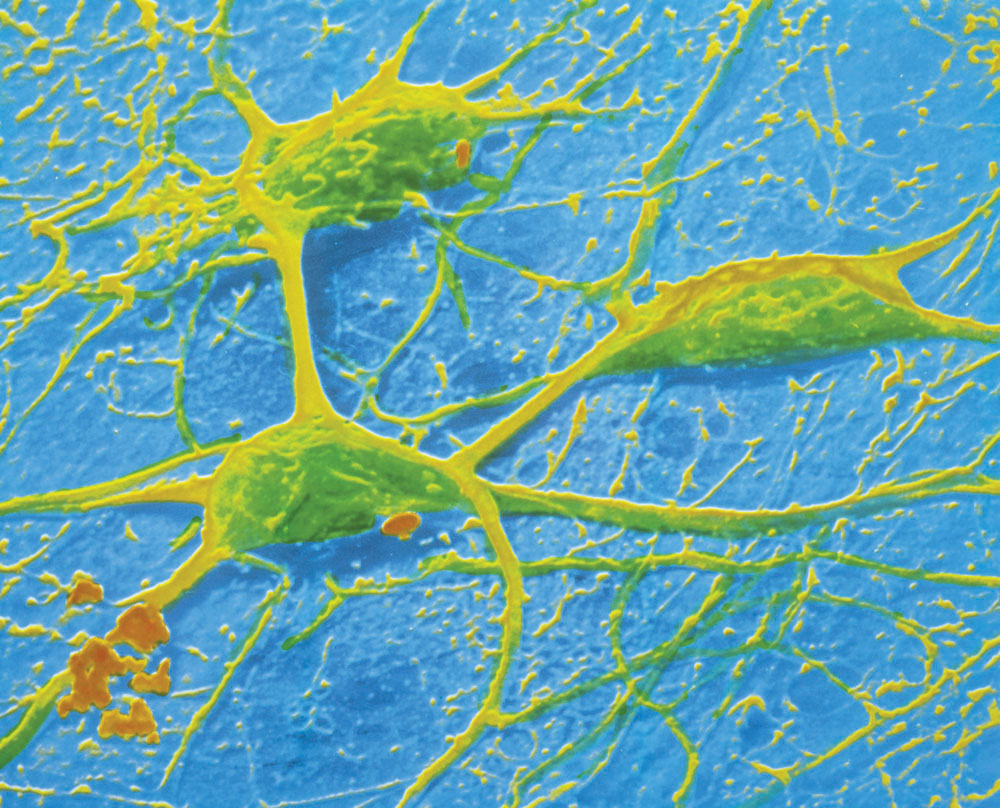

Within and between areas of the central nervous system, neurons are connected to other neurons by intricate networks of nerve fibers called axons and dendrites. Each neuron has a single axon and numerous dendrites, which spread out like the branches of a tree. The axon of one neuron meets the dendrites of other neurons at intersections called synapses, which are critical communication links within the brain.

To be more specific, neurons communicate by sending electrochemical impulses through their axons to synapses, to be picked up by the dendrites of other neurons. The dendrites bring messages to the cell bodies of their neurons, which, in turn, convey the messages via their axons to the dendrites of other neurons (see Visualizing Development, p. 131).

neurotransmitter A brain chemical that carries information from the axon of a sending neuron to the dendrites of a receiving neuron.

synaptic gap The pathway across which neurotransmitters carry information from the axon of the sending neuron to the dendrites of the receiving neuron.

Axons and dendrites do not quite touch at synapses. Instead, the electrical impulses in axons typically cause the release of chemicals called neurotransmitters, which carry information from the axon of the sending neuron, across a synaptic gap, to the dendrites of the receiving neuron (see Figure 5.4).

FIGURE 5.4

How Two Neurons Communicate The infant brain contains billions of neurons, each with one axon and many dendrites. Every electrochemical message causes thousands of neurons to fire, each transmitting the message across the synapse to neighboring neurons. This electron micrograph shows neurons greatly magnified, with their tangled but highly organized and well-VISUALIZING DEVELOPMENT: Nature, Nurture, and the Brain

Nature, Nurture, and the Brain

The mechanics of neurological functioning are varied and complex; neuroscientists hypothesize, experiment, and discover more each day. Brain development begins with genes and other biological elements, but hundreds of epigenetic factors affect brain development from the first to the final minutes of life. Particularly important in human development are experiences: plasticity means that dendrites form or atrophy is response to nutrients and events. The effects of early nurturing experiences are lifelong, as proven many times in mice; research on humans suggest similar effects.

NATURE

The link between one neuron and another is shown in this simplified diagram. The infant brain contains billions of neurons, each with one axon and many dendrites. Every electrochemical message to or from the brain causes thousands of neurons to fire simultaneously, each transmitting the message across the synapse to neighboring neurons.

NURTURE

In experiments with baby mice, those that were frequently licked and nuzzled by their mothers exhibited very different behaviors from those that were neglected.

THE BRAIN

Social scientists now believe that every aspect of early life affects brain patterns: Each experience activates and prunes neurons, such that the firing patterns from one axon to another dendrite reflect the past. When a mother mouse licks her newborn babies, that reduces methylation of a gene (called Nr3cl), allowing increased serotonin to be released by the hypothalamus. That serotonin not only increases momentary pleasure (mice love being licked) but also starts a chain of epigenetic responses that reduce stress hormones from many parts of the brain and body, including the adrenal glands. The effects are lifelong, as proven many times in mice. In humans, a mother’s gentle stroking and cuddling of her newborn seem to affect the baby similarly.

Experiences and Pruning

At birth, the brain contains at least 100 billion neurons, more than a person needs. However, the newborn’s brain has far fewer dendrites and synapses than the person will eventually possess. During the first months and years, rapid growth and refinement in axons, dendrites, and synapses occurs, especially in the cortex. Dendrite growth is the major reason that brain weight triples from birth to age 2 (Johnson, 2010).

An estimated fivefold increase in the number of dendrites in the cortex occurs in the 24 months after birth, with about 100 trillion synapses being present at age 2. According to one expert, “40,000 new synapses are formed every second in the infant’s brain” (Schore & McIntosh, 2011, p. 502).

This extensive postnatal brain growth is highly unusual for mammals. It occurs in humans because heads cannot grow enough before birth to contain the brain networks needed to sustain human development. Although prenatal brain development is remarkable, it is limited because the human pelvis is relatively small, so the baby’s head must be much smaller than an adult’s head in order to make birth possible. For that reason, unlike other mammals, humans must nurture and protect their offspring for more than a decade while the child’s brain continues to develop (Konner, 2010).

transient exuberance The great but temporary increase in the number of dendrites that develop in an infant’s brain during the first two years of life.

pruning When applied to brain development, the process by which unused connections in the brain atrophy and die.

Early dendrite growth is called transient exuberance: exuberant because it is so rapid and transient because some of it is temporary. The expansive growth of dendrites is followed by pruning. Just as a gardener might prune a rose bush by cutting away some growth to enable more, or more beautiful, roses to bloom, unused brain connections atrophy and die, enabling the brain to develop in accord with the sociocultural context (Stiles & Jernigan, 2010).

The details of brain structure and growth depend on genes and maturation but even more on experience (Stiles & Jernigan, 2010). Some dendrites wither away because they are never used—

Strangely enough, this loss of dendrites increases brainpower. The space between neurons in human brains, for instance—

Some children with intellectual disabilities have “a persistent failure of normal synapse pruning” (Irwin et al., 2002, p. 194). That makes thinking and learning difficult. One sign of autism is rapid brain growth, suggesting too little pruning (Hazlett et al., 2011). Indeed, studies of brain development in autistic children suggest that their brains develop normally for the first six months, but then synapses do not develop as they should, so that by the second year of life symptoms of autism become evident (Landa et al., 2013).

Yet just as too little pruning creates problems, so does too much pruning. Brain sculpting is attuned to experience: The appropriate links in the brain need to be established, protected, and strengthened while inappropriate ones are eliminated. One group of scientists speculates that “lack of normative experiences may lead to overpruning of neurons and synapses, both of which may lead to reduction of brain activity” (Moulson et al., 2009, p. 1051).

Especially for Parents of Grown Children Suppose you realize that you seldom talked to your children until they talked to you and that you often put them in cribs and playpens. Did you limit their brain growth and their sensory capacity?

Response for Parents of Grown Children: Probably not. Brain development is programmed to occur for all infants, requiring only the stimulation that virtually all families provide—

Another group suggests that infants who are often hungry, or hurt, or neglected may develop brains that compensate—

Harm and Protection

Most infants develop well within their culture, and head-

Those essential experiences are called expectant because the brain requires them to develop normally and therefore “expects” them to be provided in much the same way the stomach expects food. That contrasts with dependent experiences, which vary from family to family.

experience-

Experience-

experience-

Experience-

Another essential experience that every infant brain expects is sensory stimulation. Playing with a young baby, allowing varied sights, sounds, touches, and movements (arm waving in the early months, walking later on) are all fodder for brain connections. Severe lack of stimulation (e.g., a baby who never hears speech) stunts the brain. As one review of early brain development explains, “enrichment and deprivation studies provide powerful evidence of…widespread effects of experience on the complexity and function of the developing system” (Stiles & Jernigan, 2010, p. 345).

This does not mean that babies require spinning, buzzing, multitextured, and multicolored toys. In fact, such toys may be a waste of money. Infants are fascinated by simple objects and facial expressions. Fortunately, although elaborate infant toys are not needed, there is no evidence that they harm the brain; babies prevent overstimulation by ignoring them. A simple application of what has been learned about the prefrontal cortex is that hundreds of objects, from the very simple to the quite complex, can capture an infant’s attention.

However, because the prefrontal cortex is underdeveloped in infancy, the brain is not yet under thoughtful control. For instance, it is useless to insist that an infant stop crying: Babies are too immature to decide to stop crying, as adults do. If adults do not understand this fact, the results can be tragic.

shaken baby syndrome A life-

If a frustrated caregiver shakes a crying baby sharply and quickly, that can cause shaken baby syndrome, a life-

The fact that infant brains respond to their circumstances suggests that waiting for evidence of child mistreatment is waiting too long. In the first months of life babies adjust to their world, becoming withdrawn and quiet if their caregivers are depressed, or becoming loud and demanding if that is the only way they can get fed. In both these circumstances, they learn destructive habits. Thus, since development is dynamic and interactive, caregivers need help from the start, not when harmful systems are established (Tronick & Beeghly, 2011).

self-

The word systems is crucial here. Almost every baby experiences something stressful—

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

Face Recognition

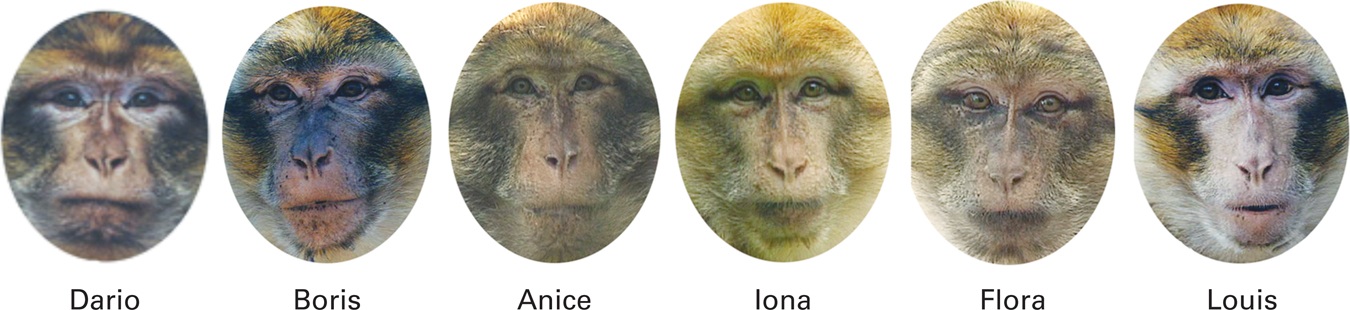

Unless you have prosopagnosia (face blindness, relatively uncommon), the fusiform face area of your brain is astonishingly adept at face recognition. This area is primed among newborns, who are quicker to recognize a face they have just seen once than older children and adults (Zeifman, 2013). However, every face is fascinating early in life: Babies stare at pictures of monkey faces and photos of human ones, at drawings and toys with faces, as well as at live faces.

Soon, experiences refine perception (De Heering et al., 2010). By 3 months, babies smile more readily at familiar people and are more accurate at differentiating faces from their own ethnic group (called the own-

The importance of early experience is confirmed by two studies. From 6 to 9 months, infants were repeatedly shown a book with pictures of six monkey faces, each with a name written on the page (see photo). One-

At 9 months, infants in all three groups viewed pictures of six unfamiliar monkeys. The infants who had heard names of monkeys were better at distinguishing one new monkey from another than were the infants who saw the same picture book but did not hear each monkey’s name (Scott & Monesson, 2010).

Many children and adults do not notice the individuality of newborns. Some even claim that “all babies look alike.” However, the second interesting study found that 3-

Sleep

One consequence of brain maturation is the ability to sleep through the night. Newborns cannot do this. Normally, they sleep 15 to 17 hours a day, in one-

Wide variation is particularly apparent in the early weeks. As reported by parents (who might exaggerate), one new baby in 20 sleeps 9 hours or fewer per day and one in 20 sleeps 19 hours or more (Sadeh et al., 2009).

Sleep specifics vary not only because of biology (age and genes) but also because of the social environment. Full-

REM (rapid eye movement) sleep A stage of sleep characterized by flickering eyes behind closed lids, dreaming, and rapid brain waves.

Over the first months, the relative amount of time in various stages of sleep changes. Babies born preterm may always seem to be dozing. About half of the sleep of full-

Overall, 25 percent of children under age 3 have sleeping problems, according to parents surveyed in an Internet study of more than 5,000 North Americans (Sadeh et al., 2009). Sleep problems are more troubling for parents than for infants. This does not render the problems insignificant, however; overtired parents may be less patient and responsive (Bayer et al., 2007).

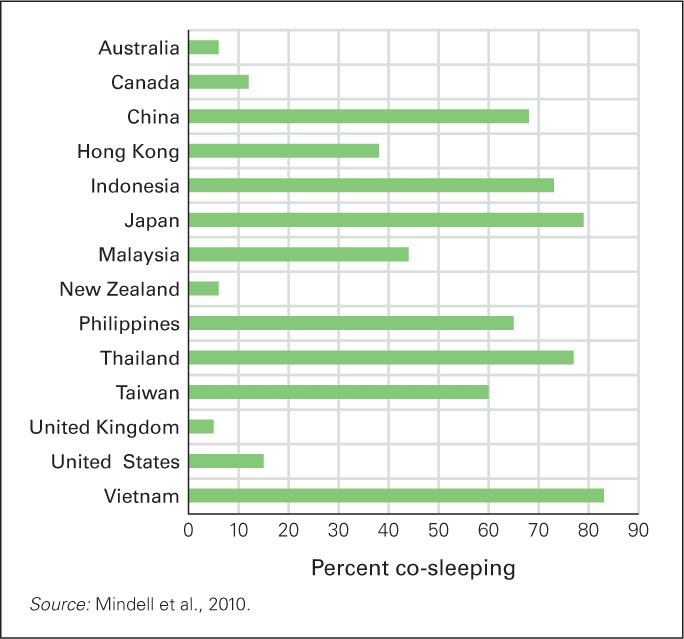

One problem for parents is that advice about where infants should sleep varies. Some suggest that infants should sleep beside their parents—

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

Where Should Babies Sleep?

co-

Traditionally, most middle-

Even today, at baby’s bedtime, Asian and African mothers worry more about separation, whereas European and North American mothers worry more about lack of privacy. A 19-

FIGURE 5.5

Awake at Night Why the disparity between Asian and non-This difference in practice may seem related to income, since low-

The argument for co-

Yet the argument against co-

One reason for opposite practices is that adults are affected by their own early experiences. This phenomenon is called ghosts in the nursery because new parents bring decades-

For example, compared with Israeli adults who had slept near their parents as infants, those who had slept communally with other infants (as sometimes occurred on kibbutzim) were more likely to interpret their own infants’ nighttime cries as distress, requiring comfort (Tikotzky et al., 2010). That is how a ghost affects current behavior: If parents think their crying babies are frightened, lonely, and distressed, they want to respond. Quick responses are easier with co-

But remember that infants learn from their earliest experiences. If babies become accustomed to bed-

Developmentalists hesitate to declare any particular pattern best because the issue is “tricky and complex” (Gettler & McKenna, 2010, p. 77). Sleeping alone may encourage independence—

Especially for New Parents You are aware of cultural differences in sleeping practices, which raises a very practical issue: Should your newborn sleep in bed with you?

Response for New Parents: From the psychological and cultural perspectives, babies can sleep anywhere as long as the parents can hear them if they cry. The main consideration is safety: Infants should not sleep on a mattress that is too soft, nor beside an adult who is drunk or drugged. Otherwise, each family should decide for itself.

SUMMING UP

Weight and height increase markedly in the first two years. Babies triple their birth weight by age 1 and add more than a foot between birth and age 2. Norms for height and weight are expressed in percentiles, because children who are relatively big or small typically continue on that path.

Brain development is rapid during infancy, particularly development of the axons, dendrites, and synapses within the cortex. The timing of brain growth is under genetic control, as various parts of the cortex mature on schedule. Experience—