Surviving in Good Health

Surviving in Good Health

Although precise worldwide statistics are unavailable, at least 9 billion children were born between 1950 and 2010. More than 1 billion of them died before age 5. Although 1 billion is far too many, twice that many would have died without recent public health measures. One young child in 5 died in 1950, as did 1 child in 17 in 2010 (United Nations, 2012). Those are official statistics; probably millions more died in the poorest nations without being counted. In earlier centuries more than half of all newborns died in infancy.

Better Days Ahead

In the twenty-

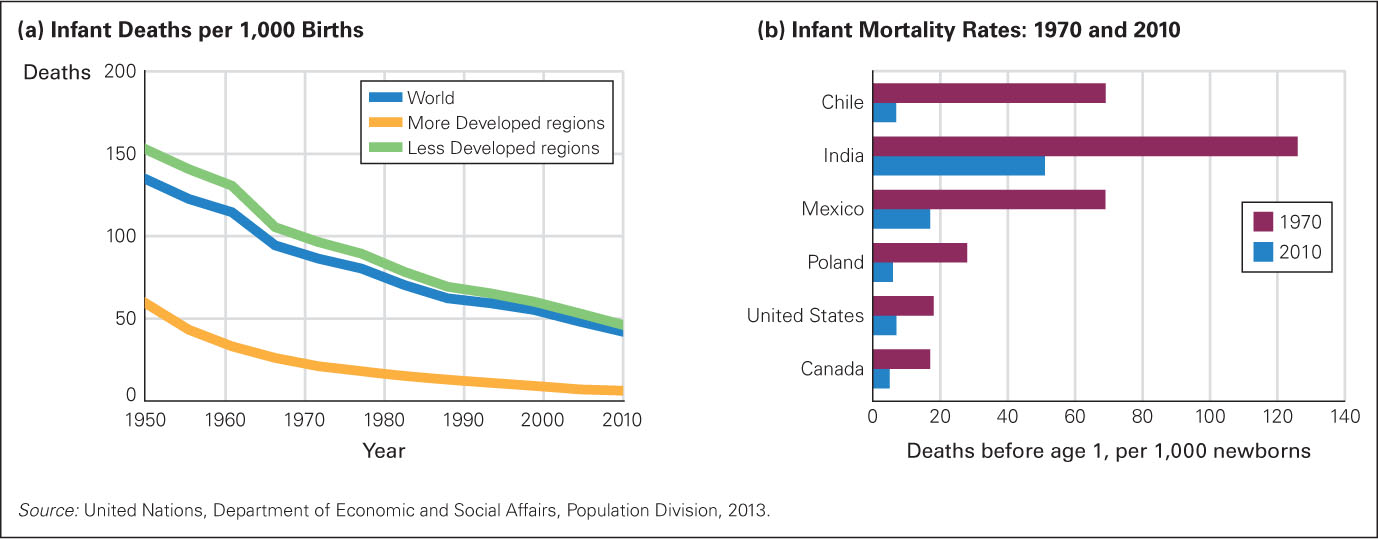

FIGURE 5.6

More Babies Are Surviving Improvements in public health—

The world death rate in the first five years of life has dropped about 2 percent per year since 1990 (Rajaratnam et al., 2010). Public health measures (clean water, nourishing food, immunization) deserve most of the credit. Further, as more children survive, parents focus more effort on each child.

For example, when parents expect every newborn to live, they have fewer babies. That advances the national economy, which can provide better schools and health care. Infant survival and maternal education are the two main reasons the world’s 2010 fertility rate is half what the rate was in 1950 (Bloom, 2011; Lutz & K. C., 2011).

If public health professionals were more available, the current infant death rate would be cut in half again, because public health includes measures to help parents as well as children, via better food distribution, less violence, more education, cleaner water, and more widespread immunization (Farahani et al., 2009).

Immunization

immunization A process that stimulates the body’s immune system by causing production of antibodies to defend against attack by a particular contagious disease. Creation of antibodies may be accomplished either naturally (by having the disease), by injection, by drops that are swallowed, or by a nasal spray. (These imposed methods are also called vaccination.)

Immunization primes the body’s immune system to resist a particular disease. Immunization (often via vaccination) is said to have had “a greater impact on human mortality reduction and population growth than any other public health intervention besides clean water” (J. P. Baker, 2000, p. 199). Immunization has been developed for measles, mumps, whooping cough, smallpox, pneumonia, polio, and rotavirus, which no longer kill hundreds of thousands of children each year.

It used to be that the only way to become immune to these diseases was to catch them, sicken, and recover. The immune system would then produce antibodies to prevent recurrence. Beginning with smallpox in the nineteenth century, doctors discovered that giving a small dose of the virus to healthy people who have not had the disease stimulates the same antibodies. (Immunization schedules, with U.S. recommendations, appear in Appendix A. Most of the vaccines listed reduce the risk of child death in every nation. However, specifics vary; caregivers need to heed local health authorities.)

Especially for Nurses and Pediatricians A mother refuses to have her baby immunized because she wants to prevent side effects. She wants your signature for a religious exemption, which in some jurisdictions allows the mother to refuse vaccination. What should you do?

Response for Nurses and Pediatricians: It is difficult to convince people that their method of child rearing is wrong, although you should try. In this case, listen respectfully and then describe specific instances of serious illness or death from a childhood disease. Suggest that the mother ask her grandparents if they knew anyone who had polio, tuberculosis, or tetanus (they probably did). If you cannot convince this mother, do not despair: Vaccination of 95 percent of toddlers helps protect the other 5 percent. If the mother has genuine religious reasons, talk to her clergy adviser.

Success and Survival

Stunning successes in immunization include the following:

- Smallpox, the most lethal disease for children in the past, was eradicated worldwide as of 1980. Vaccination against smallpox is no longer needed.

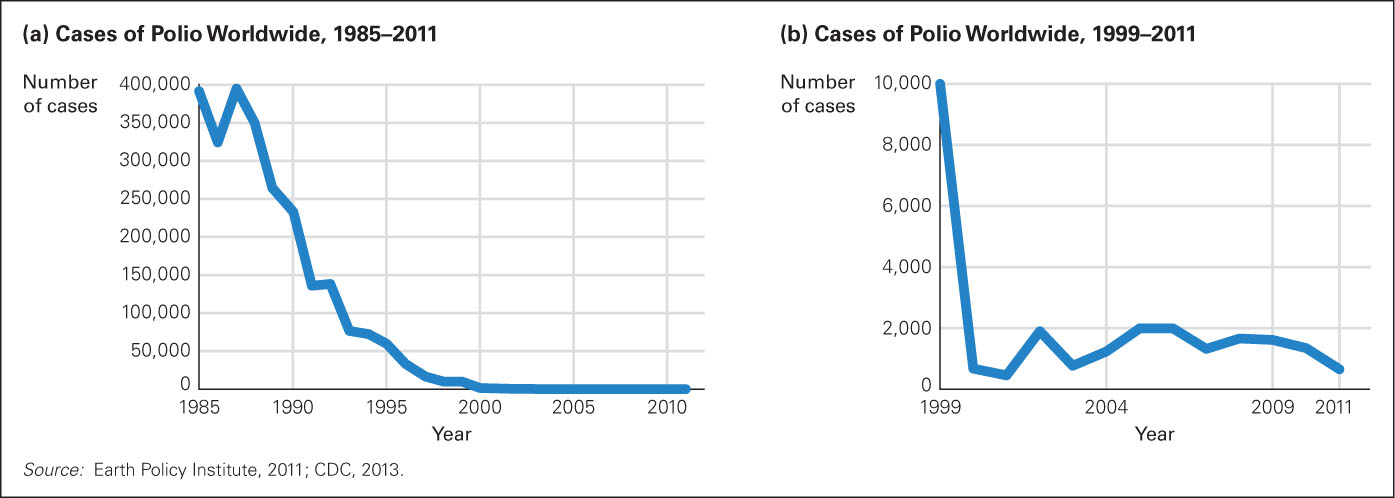

- Polio, a crippling and sometimes fatal disease, is rare. Widespread vaccination, begun in 1955, eliminated polio in the Americas. Only 784 cases were reported anywhere in the world in 2003. In the same year, however, rumors halted immunization in northern Nigeria. Polio reappeared, sickening 1,948 people in 2005, almost all of them in West Africa. Then public health workers and community leaders campaigned to increase immunization, and Nigeria’s polio rate fell again to 21 in 2010. However, poverty and wars in South Asia prevented immunization: Worldwide, 650 cases were reported in 2011, primarily in Afghanistan, India, Nigeria, and Pakistan (De Cock, 2011; World Health Organization, 2012; Roberts, 2013). (See Figure 5.7.)

- Measles (rubeola, not rubella) is disappearing, thanks to a vaccine developed in 1963. Prior to that time, 3 to 4 million cases occurred each year in the United States alone (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2007). In 2010 in the United States, only 61 people had measles, most of them born in nations without widespread immunization (MMWR, January 7, 2011). The number of reported cases rose again in 2011, when 222 were reported to have measles, 17 of which were brought into the United States from other countries, including countries in Europe and Asia. The other 215 occurred because too many children are unvaccinated (MMWR, April 20, 2012).

FIGURE 5.7

Not Yet Zero Many public health advocates hope polio will be the next infectious disease to be eliminated worldwide, as is the case in almost all of North America. The number of cases has fallen dramatically worldwide (a). However, there was a discouraging increase in polio rates from 2003 to 2005 (b).Immunization protects not only from temporary sickness or death but also from complications, including deafness, blindness, sterility, and meningitis. Sometimes the damage from illness is not apparent until decades later. Having mumps in childhood, for instance, can cause sterility and doubles the risk of schizophrenia in adulthood (Dalman et al., 2008).

Some people cannot be safely immunized, including the following:

- Embryos, who may be born blind, deaf, and brain-

damaged if their pregnant mother contracts rubella (German measles) - Newborns, who may die from a disease that is mild in older children

- People with impaired immune systems (HIV-

positive, aged, or undergoing chemotherapy), who can become deathly ill

Fortunately, each vaccinated child stops transmission of the disease and thus protects others, a phenomenon called herd immunity. Although specifics vary by disease, usually if 90 percent of the people in a community (a herd) are immunized, the disease does not spread to those who are vulnerable. Without herd immunity, some community members die of a “childhood” disease.

Problems with Immunization

Infants may react to immunization by being irritable or even feverish for a day or so, to the distress of their parents. However, parents do not notice if their child does not get polio, measles, or so on. Before the varicella (chicken pox) vaccine, more than 100 people in the United States died each year from that disease, and 1 million were itchy and feverish for a week. Now almost no one dies of varicella, and far fewer get chicken pox.

Many parents are concerned about the potential side effects of vaccines. Whenever something seems to go amiss with vaccination, the media broadcasts it, which frightens parents. As a result, the rate of missed vaccinations in the United States has been rising over the past decade. This horrifies public health workers, who, taking a longitudinal and society-

Doctors agree that vaccines “are one of the most cost-

Nutrition

Infant mortality worldwide has plummeted in recent years. Several reasons have already been mentioned. One more measure has made a huge difference: better nutrition.

Breast Is Best

Ideally, nutrition starts with colostrum, a thick, high-

Compared with formula based on cow’s milk, human milk is sterile; always at body temperature; and rich in many essential nutrients for brain and body (Drover et al., 2009). Babies who are exclusively breast-

Breast-

The specific fats and sugars in breast milk make it more digestible and better for the brain than any substitute (Drover et al., 2009; Riordan, 2005). The composition of breast milk adjusts to the age of the baby, with milk for premature babies distinct from that for older infants. Quantity increases to meet the demand: Twins and even triplets can grow strong while being exclusively breast-

Formula-

SELECTSTOCK/GETTY IMAGES.

For all these reasons, doctors worldwide recommend breast-

| For the Baby | For the Mother |

|---|---|

|

|

| For the Family | |

|

|

| Sources: Beilin & Huang, 2008; Riordan & Wambach, 2009; Schanler, 2011; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2011. | |

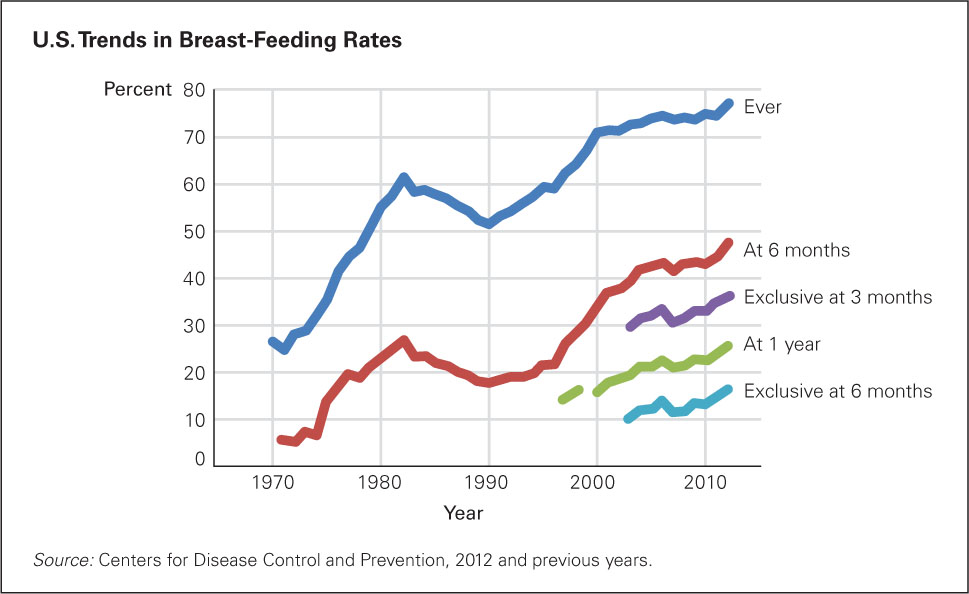

Breast-

FIGURE 5.8

A Smart Choice In 1970, educated women were taught that formula was the smart, modern way to provide nutrition—Since formula-

Malnutrition

protein-

stunting The failure of children to grow to a normal height for their age due to severe and chronic malnutrition.

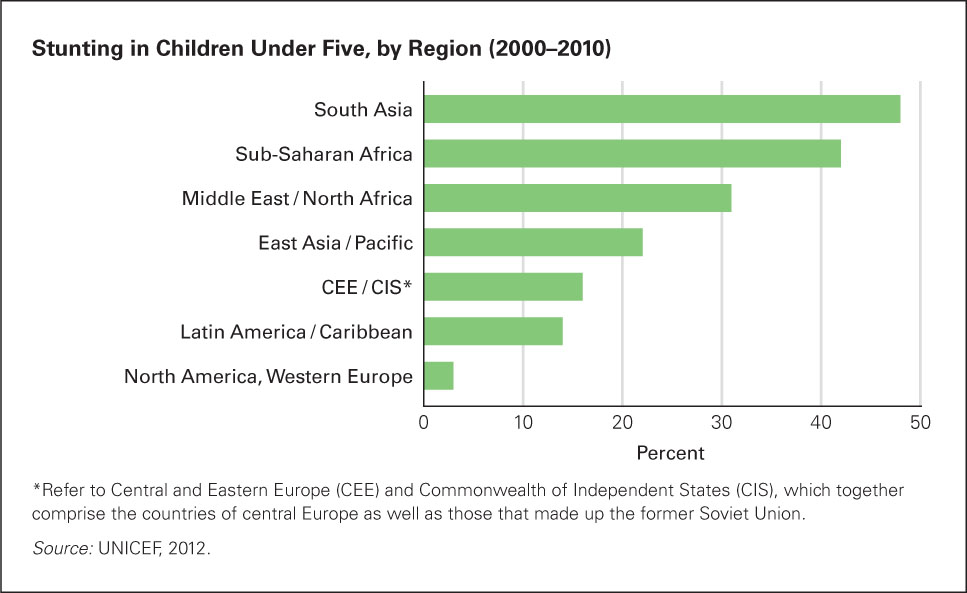

Protein-

FIGURE 5.9

Genetic? The data show that basic nutrition is still unavailable to many children in the developing world. Some critics contend that Asian children are genetically small and therefore that Western norms make it appear as if India and Africa have more stunted children than they really do. However, children of Asian and African descent born and nurtured in North America are as tall as those of European descent. Thus, malnutrition, not genes, accounts for most stunting worldwide.wasting The tendency for children to be severely underweight for their age as a result of malnutrition.

Even worse is wasting, when children are severely underweight for their age and height (2 or more standard deviations below average). Many nations, especially in East Asia, Latin America, and central Europe, have seen improvement in child nutrition in the past decades, with an accompanying decrease in wasting and stunting.

© DANG NGO/ZUMAPRESS.COM

In some other nations, however, primarily in Africa, wasting has increased. And in several nations in South Asia, about half the children over age 5 are stunted and half of them are also wasted, at least for a year (World Bank, 2010). In some nations, the traditional diet for young children does not provide sufficient vitamins, fat, and protein for robust health. As a result, energy is reduced and normal curiosity is absent (Osorio, 2011). Young children naturally want to understand whatever they can: A child with no energy is also a child who is not learning.

Chronically malnourished infants and children suffer in three additional ways (World Bank, 2010):

- Their brains may not develop normally. If malnutrition has continued long enough to affect height, it may also have affected the brain.

- Malnourished children have no body reserves to protect them against common diseases. About half of all childhood deaths occur because malnutrition makes a childhood disease lethal.

marasmus A disease of severe protein-

calorie malnutrition during early infancy, in which growth stops, body tissues waste away, and the infant eventually dies. Some diseases result directly from malnutrition—kwashiorkor A disease of chronic malnutrition during childhood, in which a protein deficiency makes the child more vulnerable to other diseases, such as measles, diarrhea, and influenza.

both marasmus during the first year, when body tissues waste away, and kwashiorkor after age 1, when growth slows down, hair becomes thin, skin becomes splotchy, and the face, legs, and abdomen swell with fluid (edema).

Prevention, more than treatment, is needed. Sadly, some children hospitalized for marasmus or kwashiorkor die even after feeding because their digestive systems are already failing (Smith et al., 2013). Ideally, prenatal nutrition, then breast-

A study of two of the poorest African nations (Niger and Gambia) found several specific factors that reduced the likelihood of wasting and stunting: breast-

But we should not close this chapter by blaming the mothers or the cultures. Sometimes culture helps, as you will now see.

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome

sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) A situation in which a seemingly healthy infant, usually between 2 and 6 months old, suddenly stops breathing and dies unexpectedly while asleep.

Every year until the mid-

One scientist named Susan Beal studied every SIDS death in South Australia for years, noting dozens of circumstances, seeking factors that increased the risk. Some things did not matter (such as birth order), and others increased the risk (such as maternal smoking and lambskin blankets).

Beal discovered an ethnic variation: Australian babies of Chinese descent died of SIDS far less often than did Australian babies of European descent. Genetic? Most experts thought so. But Beal’s scientific observation led her to note that Chinese babies slept on their backs, contrary to the European or American custom of stomach-

Beal thought of a new hypothesis: that sleeping position mattered. To test that hypothesis, she convinced a large group of non-

Her published reports (Beal, 1988) caught the attention of doctors in the Netherlands, one of the many Western nations where babies almost always slept on their stomachs. Two Dutch scientists (Engelberts & de Jong, 1990) recommended back-

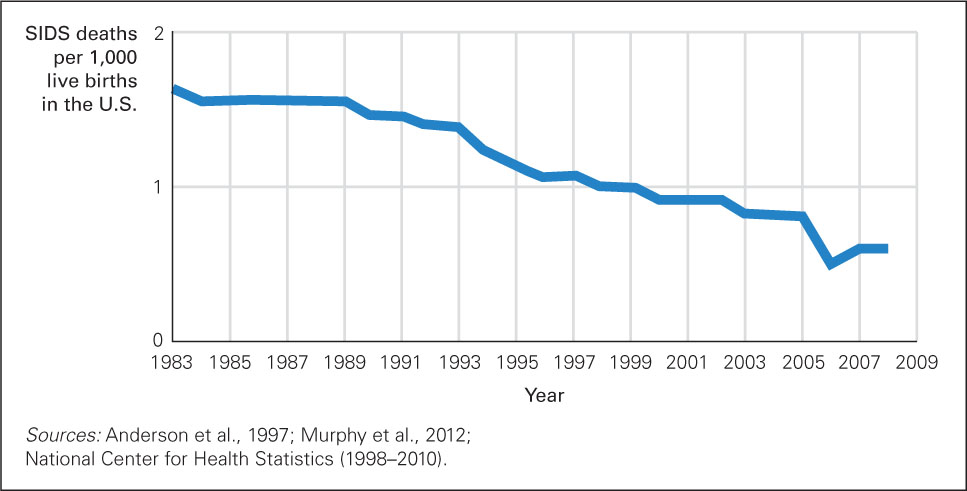

Replication and application spread. By 1994, a “Back to Sleep” campaign in nation after nation cut the SIDS rate dramatically (Kinney & Thach, 2009; Mitchell, 2009). In the United States, in 1984, SIDS killed 5,245 babies; in 1996 it was down to 3,050; and since 2000, about 2,000 a year (see Figure 5.10). The campaign has been so successful that physical therapists report that babies crawl later than they used to, and so they advocate tummy time—putting awake infants on their stomachs to develop their muscles (Zachry & Kitzmann, 2011).

We close with the saga of SIDS because it is a dramatic example of many themes of this chapter. First, infant care is complex, with many factors interacting to produce each accomplishment. Stomach-

FIGURE 5.10

Before and After Detailed U.S. data on SIDS are available only for the past 25 years, but as best we know, the rate was steady at about 1 baby in every 700 throughout most of the twentieth century and has been even lower after 2008, at about 1 baby in every 2000.The success in reducing SIDS underscores several themes first described in Chapter 1. Because of developmental science, with a multidisciplinary and multicultural perspective, in the United States alone about 40,000 children and young adults are alive today because they were born after 1990 and thus escaped sudden infant death.

SUMMING UP

Various public health measures have saved billions of infants in the past century. Immunization protects those who are inoculated and also halts the spread of contagious diseases (via herd immunity). Smallpox has been eliminated, and many other diseases are rare except in regions of the world that public health professionals have not reached.

Breast milk is the ideal infant food, improving development for decades and reducing infant malnutrition and death. Fortunately, rates of breast-