Language: What Develops in the First Two Years?

Language: What Develops in the First Two Years?

The brains of no other species have anything approaching the neurons and networks that support the 6,000 or so human languages. Many other animals communicate, but the human linguistic ability at age 2 far surpasses that of full-

The Universal Sequence

The sequence of language development is the same worldwide (see At About This Time). Some children learn several languages, some only one, some learn rapidly and others slowly, but they all follow the same path. Even deaf infants who become able to hear (thanks to cochlear implants) follow the sequence, catching up to their age-

Listening and Responding

Language learning begins before birth (Dirix et al., 2009). Newborns prefer to listen to the language their mother spoke when they were in the womb, not because they understand the words, of course, but because they are familiar with the rhythm, the sounds, and the cadence.

Surprisingly, newborns of bilingual mothers differentiate between both languages (Heinlein et al., 2010). Data were collected on 94 newborns (0 to 5 days old) in a large hospital in Vancouver, Canada. Half were born to mothers who spoke both English and Tagalog (the native language of Filipinos), one-

The infants in all three groups sucked as they listened to 10 minutes of recorded sentences in English or Tagalog matched for pitch, duration, and number of syllables. Most of them with bilingual mothers preferred Tagalog, whereas those with monolingual mothers preferred English. The Chinese bilingual babies (who had never heard Tagalog) nonetheless preferred it. The researchers believe that they liked Tagalog because the rhythm of that Asian language is more similar to Chinese than to English (Heinlein et al., 2010).

| The Development of Spoken Language in the First Two Years | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age* | Means of Communication | |

| Newborn | Reflexive communication— |

|

| 2 months | A range of meaningful noises— |

|

|

3- |

New sounds, including squeals, growls, croons, trills, vowel sounds. | |

|

6- |

Babbling, including both consonant and vowel sounds repeated in syllables. | |

| 10- |

Comprehension of simple words; speechlike intonations; specific vocalizations that have meaning to those who know the infant well. Deaf babies express their first signs; hearing babies also use specific gestures (e.g., pointing) to communicate. | |

| 12 months | First spoken words that are recognizably part of the native language. | |

| 13- |

Slow growth of vocabulary, up to about 50 words. | |

| 18 months | Naming explosion— |

|

| 21 months | First two- |

|

| 24 months | Multiword sentences. Half the toddler’s utterances are two or more words long. | |

| *The ages in this table reflect norms. Many healthy, intelligent children attain each linguistic accomplishment earlier or later than indicated here. | ||

Young infants attend to voices more than to mechanical sounds (a clock ticking) and look closely at the facial expressions of someone talking to them (Minagawa-

Infants’ ability to distinguish sounds in the language they hear improves, whereas the ability to hear sounds never spoken in their native language (such as how an “r” or an “l” is pronounced) deteriorates (Narayan et al., 2010). If parents want a child to speak two languages, they must speak both of them to their infant.

child-

In every language, adults use higher pitch, simple words, repetition, varied speed, and exaggerated emotional tone when talking to infants (Bryant & Barrett, 2007). This special language form is sometimes called baby talk, since it is directed to babies, and sometimes called motherese, since mothers universally speak it. Non-

No matter what term is used, child-

Especially for Nurses and Pediatricians The parents of a 6-

Response for Nurses and Pediatricians: Urge the parents to learn sign language and investigate cochlear implants. Babbling has a biological basis and begins at a specified time, in deaf as well as in hearing babies. However, deaf babies eventually begin to use gestures more and to vocalize less than hearing babies. If their infant can hear, sign language does no harm. If the child is deaf, however, lack of communication may be devastating.

Not only do infants prefer child-

Babbling

babbling An infant’s repetition of certain syllables, such as ba-

Between 6 and 9 months, babies repeat certain syllables (ma-

Toward the end of the first year, babbling begins to sound like the infant’s native language; infants imitate accents, cadence, consonants, and so on. Videotapes of deaf infants whose parents sign to them show that 10-

Many caregivers, recognizing the power of gestures, teach “baby signs” to their 6-

One early gesture is pointing, an advanced social gesture that requires understanding another person’s perspective. Most animals cannot interpret pointing; most 10-

First Words

Finally, at about 1 year, the average baby utters a few words, understood by caregivers if not by strangers. For example, at 13 months, a child named Kyle knew standard words such as mama, but he also knew da, ba, tam, opma, and daes, which his parents knew to be, respectively, “downstairs,” “bottle,” “tummy,” “oatmeal,” and “starfish.” He also had a special sound that he used to call squirrels (Lewis et al., 1999).

Gradual Beginnings

holophrase A single word that is used to express a complete, meaningful thought.

In the first months of the second year, spoken vocabulary increases gradually (perhaps one new word a week). However, meanings are learned rapidly; babies understand about 10 times more words than they can say. Initially, the first words are merely labels for familiar things (mama and dada are common), but early words are soon accompanied by gestures, facial expressions, and nuances of tone, loudness, and cadence (Saxton, 2010). Imagine meaningful communication in “Dada,” “Dada?” and “Dada!” Each is a holophrase, a single word that expresses an entire thought.

Intonation (variation in tone and pitch) is extensive in both babbling and holophrases, but it is temporarily reduced at about 12 months. Apparently, at that point infants reorganize their vocalization from universal to language-

Careful tracing of early language finds other times when vocalization slows before a burst of new talking begins; perception affects action (Pulvermüller & Fadiga, 2010). Thus neurological advances may temporarily inhibit vocalization (Parladé & Iverson, 2011).

The Naming Explosion

naming explosion A sudden increase in an infant’s vocabulary, especially in the number of nouns, that begins at about 18 months of age.

Spoken vocabulary builds rapidly once the first 50 words are mastered, with 21-

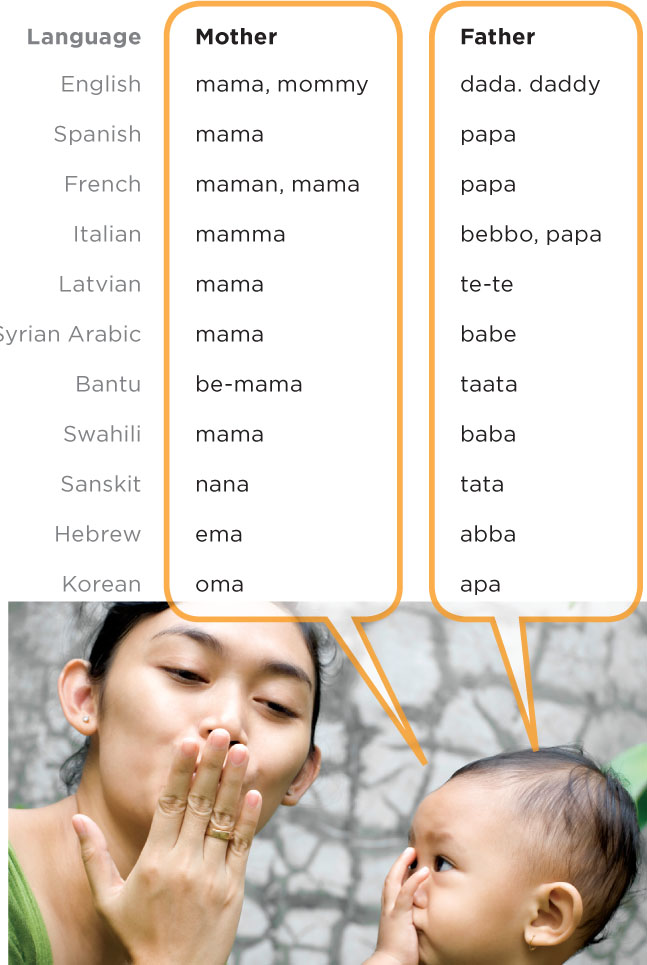

Between 12 and 18 months almost every infant learns the name of each significant caregiver (often dada, mama, nana, papa, baba, tata) and sibling (and sometimes each pet). (See Appendix A.) Other frequently uttered words refer to the child’s favorite foods (nana can mean “banana” as well as “grandma”) and to elimination (pee-

Notice that all these words have two identical syllables, each a consonant followed by a vowel sound. Many words follow that pattern—

Cultural Differences

Especially for Caregivers A toddler calls two people “Mama.” Is this a sign of confusion?

Response for Caregivers: Not at all. Toddlers hear several people called “Mama” (their own mother, their grandmothers, their cousins’ and friends’ mothers) and experience mothering from several people, so it is not surprising if they use “Mama” too broadly. They will eventually narrow the label down to one person.

Cultures and families vary in how much child-

By 5-

Parts of Speech

Although all new talkers say names, use similar sounds, and prefer nouns more than other parts of speech, the ratio of nouns to verbs and adjectives varies from place to place. For example, by 18 months, the ratio of nouns to verbs is higher in English-

One explanation goes back to the language itself. Chinese and Korean are “verb-

An alternative explanation considers the entire social context: Playing with a variety of toys and learning about dozens of objects are routine in North America, whereas East Asian cultures emphasize human interactions—

A simpler explanation is that young children are sensitive to sounds. Verbs are learned more easily if they sound like the action (Imai et al., 2008), and such verbs are more common in some languages than others.

English does not have many onomatopoeic verbs, which makes verb-

Putting Words Together

grammar All the methods—

Grammar includes all the methods that languages use to communicate meaning. Word order, prefixes, suffixes, intonation, verb forms, pronouns and negations, prepositions and articles—

For example, “Baby cry” and “More juice” follow grammatical word order. No child asks, “Juice more,” and even toddlers know that “cry baby” is not the same as “baby cry.” By age 2, children combine three words. English grammar uses subject–

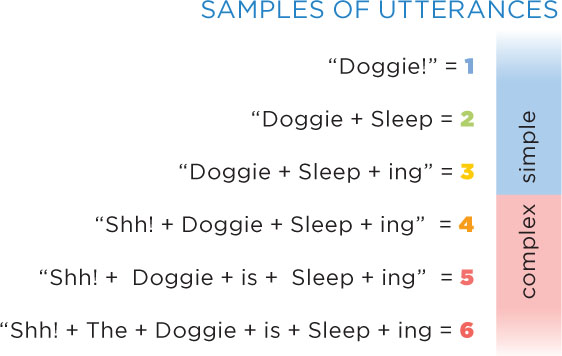

mean length of utterance (MLU) The average number of words in a typical sentence (called utterance, because children may not talk in complete sentences). MLU is often used to indicate how advanced a child’s language development is.

Children’s grammar correlates with the length of their sentences, which is why in every language mean length of utterance (MLU) is considered an accurate way to measure a child’s language progress (e.g., Miyata et al., 2013). The child who says “Baby is crying” is advanced in language development compared with the child who says “Baby crying” or simply the holophrase “Baby.”

Young children can master two languages, not just one. Children are statisticians: They implicitly track the number of words and phrases and learn those expressed most often, in one, two, or more languages (Johnson & Tyler, 2010). [Lifespan Link: Bilingual learning is discussed in detail in Chapter 9.]

Theories of Language Learning

Worldwide, people who are not yet 2 years old already speak their native tongue. They continue to learn rapidly: Some teenagers compose lyrics or deliver orations that move thousands of their co-

Answers come from three schools of thought, each of which is connected to a theory introduced in Chapter 2: behaviorism, sociocultural theory, and evolutionary psychology. The first theory says that infants are directly taught, the second that social impulses propel infants to communicate, and the third that infants understand language because of brain advances thousands of years ago that allowed survival of our species.

Theory One: Infants Need to Be Taught

The seeds of the first perspective were planted more than 50 years ago, when the dominant theory in North American psychology was behaviorism, or learning theory. The essential idea was that all learning is acquired, step-

B. F. Skinner (1957) noticed that spontaneous babbling is usually reinforced. Typically, every time the baby says “ma-

Skinner believed that most parents are excellent instructors, responding to their infants’ gestures and sounds, thus reinforcing speech (Saxton, 2010). Even in preliterate societies, parents use child-

The core ideas of this theory are the following:

- Parents are expert teachers, although other caregivers help.

- Frequent repetition is instructive, especially when linked to daily life.

- Well-

taught infants become well- spoken children.

Behaviorists note that some 3-

Especially for Educators An infant day-

Response for Educators: Probably both. Infants love to communicate, and they seek every possible way to do so. Therefore, the teachers should try to understand the baby and the baby’s parents, but they should also start teaching the baby the majority language of the school.

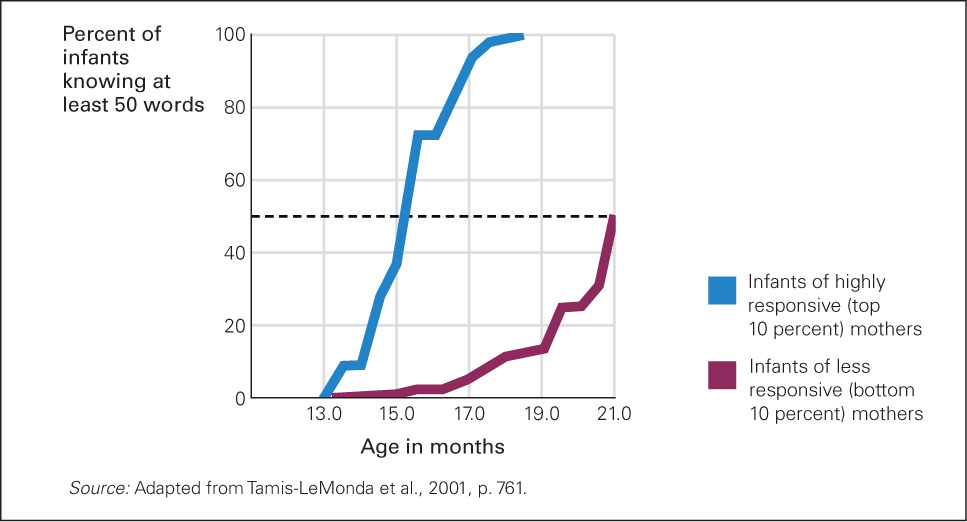

FIGURE 6.2

Maternal Responsiveness and Infants’ Language Acquisition Learning the first 50 words is a milestone in early language acquisition, as it predicts the arrival of the naming explosion and the multiword sentence a few weeks later. Researchers found that the 9-Theory Two: Social Impulses Foster Infant Language

VIKRAM RAGHUVANSHI/GETTY IMAGES

The second theory is called social-

According to this perspective, it is the emotional messages of speech, not the words, that propel communication. In one study, people who had never heard English (Shuar hunter-

Evidence for social learning comes from educational programs for children. Many 1-

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

Language and Video

Toddlers can learn to swim in the ocean, throw a ball into a basket, walk on a narrow path beside a precipice, use an iPad, cut with a sharp knife, play a guitar, say a word on a flashcard, recite a poem, utter a curse and much else—

Commercial companies recognize that toddlers love learning and that parents are eager to teach. Infants are fascinated by dynamic activity, especially when it includes movement, sound, and people. This explains the popularity of child-

In fact, scientists believe the truth is opposite the commercial claims. A famous study found that infants watching Baby Einstein were delayed in language compared to other infants (Zimmerman et al., 2007). The American Association of Pediatricians suggests no screen time (including commercial videos) for children under age 2.

These conclusions are not “robust.” That means that some interpretations of the evidence are less strong than an absolute prohibition (Ferguson, & Donnellan, 2013), but overall, most developmentalists find that, although some educational videos may help older children, videos during infancy are no “substitute for loving, face-

One product, My Baby Can Read, was pulled off the market in 2012 because experts repeatedly attacked its claims, and the cost of defending lawsuits was too high (Ryan, 2012). But many such products are still sold, and new ones appear continually. The owners of Baby Einstein lost a lawsuit in 2009, promised not to claim it was educational, and offered a refund, yet, as one critic notes:

The bottom line is that this industry exists to capitalize on the national preoccupation with creating intelligent children as early as possible, and it has become a multi-

[Ryan, 2012, p. 784]

This seems to be a battle between child experts and business leaders, with parents on both sides and infants caught in the middle. Which side are you on? More importantly, why?

Theory Three: Infants Teach Themselves

Especially for Nurses and Pediatricians Bob and Joan have been reading about language development in children. They are convinced that because language develops naturally, they need not talk to their 6-

Response for Nurses and Pediatricians: Although humans may be naturally inclined to communicate with words, exposure to language is necessary. You may not convince Bob and Joan, but at least convince them that their baby will be happier if they talk to him.

A third theory holds that language learning is genetically programmed to begin at a certain age; adults need not teach it, nor is it a by-

This perspective began soon after Skinner proposed his theory of verbal learning. Noam Chomsky (1968, 1980) and his followers felt that language is too complex to be mastered merely through step-

Noting that all young children master basic grammar according to a schedule, Chomsky cited this universal grammar as evidence that humans are born with a mental structure that prepares them to seek some elements of human language. For example, everywhere a raised tone indicates a question.

language acquisition device (LAD) Chomsky’s term for a hypothesized mental structure that enables humans to learn language, including the basic aspects of grammar, vocabulary, and intonation.

Chomsky labeled this hypothesized mental structure the language acquisition device (LAD). The LAD enables children, as their brains develop, to derive the rules of grammar quickly and effectively from the speech they hear every day, regardless of whether their native language is English, Thai, or Urdu.

Other scholars agree with Chomsky that all infants seek to use their minds to understand and speak whatever language they hear. They are eager learners, and language may be considered one more aspect of neurological maturation (Wagner & Lakusta, 2009). This idea does not strip languages and cultures of their differences in sounds, grammar, and almost everything else, but the basic idea is that “language is a window on human nature, exposing deep and universal features of our thoughts and feelings” (Pinker, 2007, p. 148).

The various languages of the world are all logical, coherent, and systematic. Infants are primed to grasp the particular language they are exposed to, making caregiver speech “not a ‘trigger’ but a ‘nutrient’” (Slobin, 2001, p. 438). There is no need for a trigger, according to theory three, because words are expected by the developing brain, which quickly and efficiently connects neurons to support whichever language the infant hears. Thus, language itself is experience-

A Hybrid Theory

Which of these three perspectives is correct? Perhaps all of them. In one monograph that included details and results of 12 experiments, the authors presented a hybrid (which literally means “a new creature, formed by combining other living things”) of previous theories (Hollich et al., 2000). Since infants learn language to do numerous things—

Although originally developed to explain acquisition of first words, mostly nouns, this theory also explains learning verbs: Perceptual, social, and linguistic abilities combine to make that possible (Golinkoff & Hirsh-

After intensive study, yet another group of scientists also endorsed a hybrid theory, concluding that “multiple attentional, social and linguistic cues” contribute to early language (Tsao et al., 2004, p. 1081). It makes logical and practical sense for nature to provide several paths toward language learning and for various theorists to emphasize one or another of them (Sebastián-

It also seems that some children learn better one way, and others, another way (Goodman et al., 2008). Parents need to talk often to their infants (theory one), encourage social interaction (theory two), and appreciate the innate abilities of the child (theory three).

As one expert concludes:

In the current view, our best hope for unraveling some of the mysteries of language acquisition rests with approaches that incorporate multiple factors, that is, with approaches that incorporate not only some explicit linguistic model, but also the full range of biological, cultural, and psycholinguistic processes involved.

[Tomasello, 2006, pp. 292–

The idea that every theory is correct in some way seems idealistic. However, scientists working on extending and interpreting research on language acquisition arrived at a similar conclusion. They contend that language learning is neither the direct product of repeated input (behaviorism) nor the result of a specific human neurological capacity (LAD). Rather, from an evolutionary perspective, “different elements of the language apparatus may have evolved in different ways,” and thus a “piecemeal and empirical” approach is needed (Marcus & Rabagliati, 2009, p. 281). In other words, no single theory can explain how babies learn language: Humans accomplish this feat in many ways.

What conclusion can we draw from research on infant cognition? That infants are active learners of language and concepts, that they seek to experiment with objects and find ways to achieve their goals. This is the cognitive version of the biosocial developments noted in Chapter 5, that babies strive to roll over, crawl, walk, and so on as soon as they can. (See Visualizing Development, p. 177.)

Now back to Uncle Henry: My cousins loved their mother because she knew instinctively that her babies wanted to learn. When they grew up they realized, as developmentalists recognize, that caregivers in the first weeks of life—

SUMMING UP

From the first days of life, babies attend to words and expressions, responding as well as their limited abilities allow—

The impressive language learning of the first two years can be explained in many ways: that caregivers must teach language, that infants learn because they are social beings, that inborn cognitive capacity propels infants to acquire language as soon as maturation makes that possible. Because infants vary in culture, learning style, and social context, a hybrid theory contends that each theory may be valid for explaining some aspects of language learning at different ages.

VISUALIZING DEVELOPMENT

Early Communication and Language Development

A COMMUNICATION MILESTONES: THE FIRST TWO YEARS

|

B UNIVERSAL FIRST WORDSAcross cultures, babies’ first words are remarkably similar. The words for mother and father are recognizable in almost any language. Most children will learn to name their immediate family and caregivers between the ages of 12 and 18 months.

PHOTO: R. EKO BINTORO/ISTOCK/THINKSTOCK

C MASTERING LANGUAGEChildrens’ use of language becomes more complex as they acquire more words and begin to master grammar and usage. A child’s utterances, or utterances, are broken down into the smallest units of language to determine their length and complexity:

SOURCE: COURTESY OF MONICA KALFUR, SLPSOURCES & CREDITS LISTED ON P. SC-

|

||||||||||||||||||||