Brain and Emotions

Brain and Emotions

Brain maturation is involved in the emotional developments just described because all emotional reactions begin in the brain (Johnson, 2010). Experience promotes specific connections between neurons and emotions.

Links between expressed emotions and brain growth are complex and thus difficult to assess and describe (Lewis, 2011). Compared with the emotions of adults, discrete emotions during early infancy are murky and unpredictable. For instance, an infant’s cry can be triggered by pain, fear, tiredness, surprise, or excitement; laughter can quickly turn to tears.

Furthermore, infant emotions may erupt, increase, or disappear for unknown reasons (Camras & Shutter, 2010). The growth of synapses and dendrites is a likely explanation, the result of past experiences and ongoing maturation.

Growth of the Brain

Many specific aspects of brain development support social emotions (Lloyd-

Cultural differences become encoded in the infant brain, called “a cultural sponge” by one group of scientists (Ambady & Bharucha, 2009, p. 342). It is difficult to measure how infant brains are molded by their context. However, one study (Zhu et al., 2007) of adults—

Researchers consider this finding to be “neuroimaging evidence that culture shapes the functional anatomy of self-

Learning About Others

The tentative social smile the infant gives to every face soon becomes a quicker and fuller smile when he or she sees a familiar, loving caregiver. This occurs because, with repeated experience, the neurons that fire together become more closely and quickly connected to each other (via dendrites and neurotransmitters).

Social preferences form in the early months and are connected not only with an individual’s face, but also with the person’s voice, touch, and smell. This is one reason adopted children are placed with their new parents in the first days of life whenever possible (a marked change from 100 years ago, when adoptions began after age 1).

Social awareness is also a reason to respect an infant’s reaction to a babysitter: If a 6-

Every experience that a person has—

Serotonin not only increased momentary pleasure (mice love being licked) but also started a chain of epigenetic responses to reduce stress hormones from many parts of the brain and body, including the adrenal glands. The effects on both brain and behavior are lifelong for mice and probably for humans as well.

For many humans, social anxiety is stronger than any other anxieties. Certainly to some extent this is genetic, but as epigenetic research finds, parenting behavior is a factor as well.

If the infant of an anxious biological mother is raised by a responsive but not anxious adoptive mother, the inherited anxiety does not materialize (Natsuaki et al., 2013). Parents need to be comforting (as with the nuzzled baby mice) but not overprotective. Fearful mothers tend to raise fearful children, but fathers who offer their infants exciting but not dangerous challenges (such as a game of chase, crawling on the floor) reduce later anxiety (Majdandži et al., 2013).

Stress

Emotions are connected to brain activity and hormones, but the connections are complicated; they are affected by genes, past experiences, and additional hormones and neurotransmitters not yet understood (Lewis, 2011). One link is clear: Excessive stress (which increases cortisol) harms the developing brain (Adam et al., 2007). The hypothalamus (discussed further in Chapter 8), in particular, grows more slowly if an infant is often frightened.

Brain scans of children who were maltreated in infancy show abnormal responses to stress, anger, and other emotions—

The likelihood that early caregiving affects the brain lifelong leads to obvious applications (Belsky & de Haan, 2011). Since infants learn emotional responses, caregivers need to be consistent and reassuring. This is not always easy—

An infant’s crying has 2 possible consequences: it may elicit tenderness and desire to soothe, or helplessness and rage. It can be a signal that encourages attachment or one that jeopardizes the early relationship by triggering depression and, in some cases, even neglect or abuse.

[J. S. Kim, 2011, p. 229]

Sometimes mothers are blamed, or blame themselves, when an infant cries. This attitude is not helpful: A mother who feels guilty or incompetent may become angry at her baby, which leads to unresponsive parenting, an unhappy child, and then hostile interactions. Years later, first-

But the opposite may occur if early crying produces solicitous parenting. Then, when the baby outgrows the crying, the parent–

SERGEI SUPINSKY/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

Temperament

temperament Inborn differences between one person and another in emotions, activity, and self-

Temperament is defined as the “biologically based core of individual differences in style of approach and response to the environment that is stable across time and situations” (van den Akker et al., 2010, p. 485). “Biologically based” means that these traits originate with nature, not nurture. Confirmation that temperament arises from the inborn brain comes from an analysis of the tone, duration, and intensity of infant cries after the first inoculation, before much experience outside the womb. Cry variations at this very early stage correlate with later temperament (Jong et al., 2010).

Temperament is not the same as personality, although temperamental inclinations may lead to personality differences. Generally, personality traits (e.g., honesty and humility) are learned, whereas temperamental traits (e.g., shyness and aggression) are genetic. Of course, for every trait, nature and nurture interact.

In laboratory studies of temperament, infants are exposed to events that are frightening or attractive. Four-

These categories originate from the New York Longitudinal Study (NYLS). Begun in the 1960s, the NYLS was the first large study to recognize that each newborn has distinct inborn traits (Thomas & Chess, 1977). According to the NYLS, by 3 months, infants manifest nine traits that cluster into the four categories just listed.

Although the NYLS began a rich research endeavor, its nine dimensions have not held up in later studies (Caspi & Shiner, 2006; Zentner & Bates, 2008). Generally, only three (not nine) dimensions of temperament are found (Else-

Effortful control (able to regulate attention and emotion, to self-

Negative mood (fearful, angry, unhappy)

Exuberant (active, social, not shy)

Each of these dimensions is associated with distinctive brain patterns as well as behavior, and each affects later personality. [Lifespan Link: Personality is discussed in Chapter 22.]

Since these temperamental traits are thought to be inborn, some developmentalists seek to discover which alleles affect specific emotions (M. H. Johnson & Fearon, 2011). For example, researchers have found that the 7-

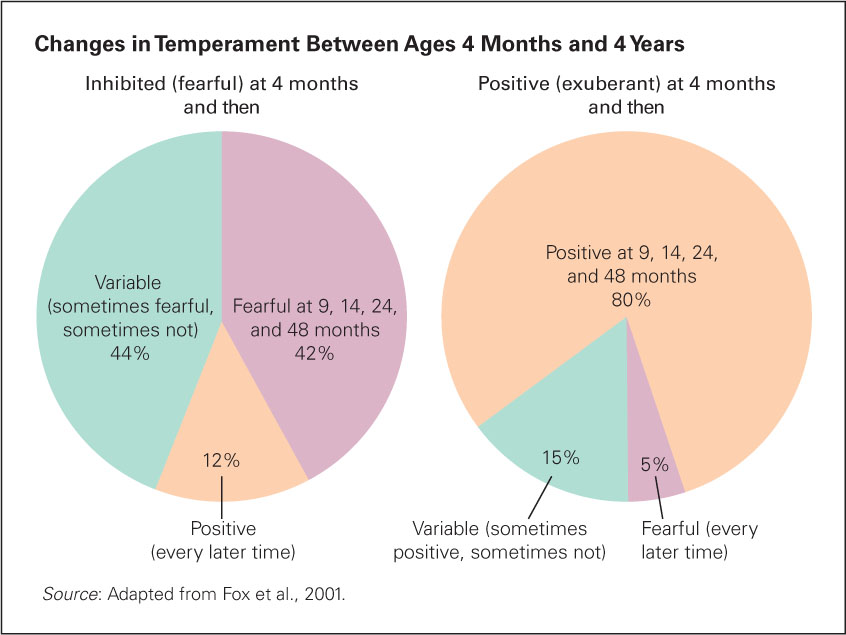

One longitudinal study analyzed temperament in the same children at 4, 9, 14, 24, and 48 months; again in middle childhood; and again at adolescence. The scientists designed laboratory experiments with specifics appropriate for the age of the children; collected detailed reports from the mothers and later from the participants themselves; and gathered observational data and physiological evidence, including brain scans. Each time, past data was reevaluated, and cross-

Half of the participants did not change much over time, reacting the same way and having similar brain-

Especially for Nurses Parents come to you with their fussy 3-

Response for Nurses: It’s too soon to tell. Temperament is not truly “fixed” but variable, especially in the first few months. Many “difficult” infants become happy, successful adolescents and adults, if their parents are responsive.

FIGURE 7.1

Do Babies’ Temperaments Change? Sometimes—The researchers found unexpected gender differences. As teenagers, the formerly inhibited boys were more likely than the average adolescent to use drugs, but the inhibited girls were less likely to do so (L. R. Williams et al., 2010). The most likely explanation is cultural: Shy boys seek to become less anxious by using drugs, but shy girls are more accepted as they are.

Continuity and change were also found in another study that described temperament using three traits (expressive, typical, and fearful). Again, typical infants stayed typical, but fearful infants were most likely to change. Only about one-

Other studies confirm that difficult infants often become easier—

Here is one very specific example. Researchers selected 32 difficult newborns (they cried quickly and loudly when an examiner tested their reflexes) and 52 somewhat difficult ones. The quality of their caregiving and bonding was measured (via attachment, soon described) at age 1. These 84 infants were assessed at 18 and 24 months on their ability to explore new objects and respond to strangers—

Highly irritable infants who received responsive parenting (secure attachment) were more social, and no less adept at exploration, than the other toddlers. By contrast, all the infants with less good care (insecure attachment) were markedly less social and less skilled than average at exploring. Impairment was especially strong for the ones who were very irritable newborns (Stupica et al., 2011).

The two patterns evident in all these studies—

SUMMING UP

Brain maturation underlies much of emotional development in the first two years. The circumstances of an infant’s life affect emotions and sculpt the brain, with long-

Temperament is inborn, with some babies much easier and others more difficult, some more social and others more shy. Such differences are partly genetic and therefore lifelong, but caregiver responses channel temperament into useful or destructive traits.