The Development of Social Bonds

The Development of Social Bonds

As you see, the social context has a powerful impact on development. So does the infant’s age, via brain maturation. With regard to emotional development, the age of the baby determines specific social interactions that lead to growth—

Synchrony

synchrony A coordinated, rapid, and smooth exchange of responses between a caregiver and an infant.

Early parent—

Both Partners Active

Detailed research reveals the symbiosis of adult–

Synchrony is evident not only in direct observation, as when watching a caregiver play with an infant too young to talk, but also via computer measurement of the millisecond timing of smiles, arched eyebrows, and so on (Messinger et al., 2010). Synchrony is a powerful learning experience for the new human. In every episode, infants read others’ emotions and develop social skills, such as taking turns and watching expressions.

One study found that mothers who took longer to bathe, feed, and diaper their infants were also most responsive. Apparently, some parents combine caregiving with emotional play, which takes longer but also allows more synchrony.

Synchrony usually begins with adults imitating infants (not vice versa) (Lavelli & Fogel, 2005), with tone and rhythm (Van Puyvelde et al., 2010). Metaphors for synchrony are often musical—

Adults respond to nuances of infant facial expressions and body motions. This helps infants connect their internal state with behaviors that are understood within their culture. Synchrony is particularly apparent in Asian cultures, perhaps because of a cultural focus on interpersonal sensitivity (Morelli & Rothbaum, 2007).

In Western cultures as well, parents and infants become partners. This relationship is crucial when the infant is at medical risk. The need for time-

Neglected Synchrony

still-

Is synchrony necessary? If no one plays with an infant, what will happen? Experiments involving the still-

In still-

To be specific, long before they can reach out and grab, infants respond excitedly to caregiver attention by waving their arms. They are delighted if the adult moves closer so that a waving arm touches the face or, even better, a hand grabs hair. You read about this eagerness for interaction (when infants try to “make interesting sights last”) in Chapter 6. In response, adults open their eyes wide, raise their eyebrows, smack their lips, and emit nonsense sounds.

In still-

Many studies reach the same conclusion: Synchrony is expected. Responsiveness aids psychosocial and biological development, evident in heart rate, weight gain, and brain maturation (Moore & Calkins, 2004; Newnham et al., 2009). Particularly in the first year, babies of depressed mothers suffer unless someone else is a sensitive partner (Bagner et al., 2010).

Attachment

Toward the end of the first year, face-

attachment According to Ainsworth, “an affectional tie” that an infant forms with a caregiver—

Instead attachment becomes evident. Actually, attachment is lifelong, beginning before birth and influencing relationships throughout life (see At About This Time). Thousands of researchers on every continent have studied attachment; all of these studies were inspired first by John Bowlby’s theories and then by Mary Ainsworth, who described mother—

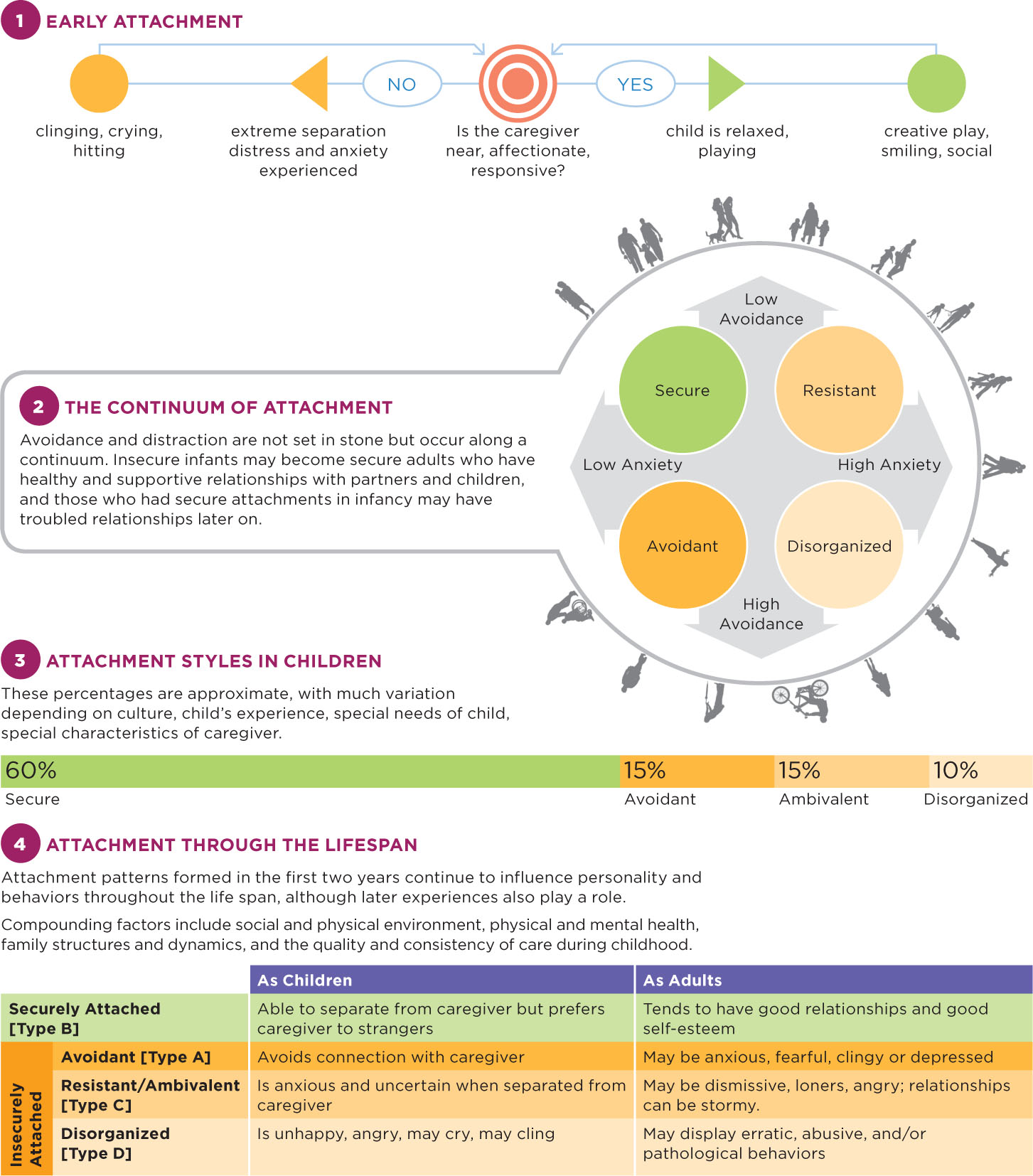

VISUALIZING DEVELOPMENT

Developing Attachment

Attachment begins at birth and can influences relationships throughout the life span. But maturation, context, and past experience also play a role. Much depends not only on the ways in which parents and babies bond, but also on the quality and consistency of caregiving, the safety and security of the home environment, and individual and family experience. While the patterns set in infancy may echo in later life, they are not determinative.

SOURCES & CREDITS LISTED ON P. SC-

| Stages of Attachment | ||

|---|---|---|

| Birth to 6 weeks | Preattachment. Newborns signal, via crying and body movements, that they need others. When people respond positively, the newborn is comforted and learns to seek more interaction. Newborns are also primed by brain patterns to recognize familiar voices and faces. | |

| 6 weeks to 8 months | Attachment in the making. Infants respond preferentially to familiar people by smiling, laughing, babbling. Their caregivers’ voices, touch, expressions, and gestures are comforting, often overriding the infant’s impulse to cry. Trust (Erikson) develops. | |

| 8 months to 2 years |

Classic secure attachment. Infants greet the primary caregiver, play happily when he or she is present, show separation anxiety when the caregiver leaves. Both infant and caregiver seek to be close to each other (proximity) and frequently look at each other (contact). In many caregiver– |

|

| 2 to 6 years |

Attachment as launching pad. Young children seek their caregiver’s praise and reassurance as their social world expands. Interactive conversations and games (hide- |

|

| 6 to 12 years | Mutual attachment. Children seek to make their caregivers proud by learning whatever adults want them to learn, and adults reciprocate. In concrete operational thought (Piaget), specific accomplishments are valued by adults and children. | |

| 12 to 18 years | New attachment figures. Teenagers explore and make friendships independent from parents, using their working models of earlier attachments as a base. With formal operational thinking (Piaget), shared ideals and goals become influential. | |

| 18 years on | Attachment revisited. Adults develop relationships with others, especially relationships with romantic partners and their own children, influenced by earlier attachment patterns. Past insecure attachments from childhood can be repaired rather than repeated, although this does not always happen. | |

| Source: Adapted from Grobman, 2008. | ||

Signs of Attachment

Infants show their attachment through proximity-

To maintain contact in the car and to reassure the baby, some caregivers in the front seat reach back to give a hand, or install a mirror so they can see the baby and the baby can see them as they drive. As in this example, maintaining contact need not be physical: Visual or verbal connections are often sufficient.

Caregivers also are attached. They keep a watchful eye on their baby, and they initiate interactions with expressions, gestures, and sounds. Before going to sleep at midnight they might tiptoe to the crib to gaze at their sleeping infant, or, in daytime, absentmindedly smooth their toddler’s hair.

Attachment is universal, being part of the inborn social nature of the human species, but specific manifestations vary depending on the culture as well as the age of the people who are attached to each other. For instance, Ugandan mothers never kiss their infants, but they often massage them, contrary to Westerners, who rarely massage except when they are putting on lotion.

American adults might remain in contact via daily phone calls, e-

Secure and Insecure Attachment

secure attachment A relationship in which an infant obtains both comfort and confidence from the presence of his or her caregiver.

Attachment is classified into four types: A, B, C, and D (see Table 7.1). Infants with secure attachment (type B) feel comfortable and confident. The caregiver is a base for exploration, providing assurance and enabling discovery. A toddler might, for example, scramble down from the caregiver’s lap to play with an intriguing toy but periodically look back and vocalize (contact-

| Type | Name of Pattern | In Play Room | Mother Leaves | Mother Returns | Toddlers in Category (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Insecure- |

Child plays happily. | Child continues playing. | Child ignores her. | 10– |

| B | Secure | Child plays happily. | Child pauses, is not as happy. | Child welcomes her, returns to play. | 50– |

| C | Insecure- |

Child clings, is preoccupied with mother. | Child is unhappy, may stop playing. | Child is angry; may cry, hit mother, cling. | 10– |

| D | Disorganized | Child is cautious. | Child may stare or yell; looks scared, confused. | Child acts oddly— |

5– |

insecure-

insecure-

By contrast, insecure attachment (types A and C) is characterized by fear, anxiety, anger, or indifference. Some insecure children play independently without maintaining contact; this is insecure-

disorganized attachment A type of attachment that is marked by an infant’s inconsistent reactions to the caregiver’s departure and return.

Ainsworth’s original schema differentiated only types A, B, and C. Later researchers discovered a fourth category (type D), disorganized attachment. Type D infants may shift suddenly from hitting to kissing their mothers, from staring blankly to crying hysterically, from pinching themselves to freezing in place.

Among the general population, almost two-

About one-

Measuring Attachment

Strange Situation A laboratory procedure for measuring attachment by evoking infants’ reactions to the stress of various adults’ comings and goings in an unfamiliar playroom.

Ainsworth (1973) developed a now-

Researchers are trained to distinguish types A, B, C, and D. They focus on the following:

Exploration of the toys. A secure toddler plays happily.

Reaction to the caregiver’s departure. A secure toddler notices when the caregiver leaves and shows some sign of missing him or her.

Reaction to the caregiver’s return. A secure toddler welcomes the caregiver’s reappearance, usually seeking contact, and then plays again.

Attachment is not always measured via the Strange Situation; surveys and interviews are also used. Sometimes parents answer 90 questions about their children’s characteristics, and sometimes adults are interviewed extensively (according to a detailed protocol) about their relationships with their own parents, again with various specific measurements (Fortuna & Roisman, 2008).

Research measuring attachment has revealed that some behaviors that might seem normal are, in fact, a sign of insecurity. For instance, an infant who clings to the caregiver and refuses to explore the toys might be type A. Likewise, adults who say their childhood was happy and their mother was a saint, especially if they provide few specific memories, might be insecure. And young children who are immediately friendly to strangers may never have formed a secure attachment (Tarullo et al., 2011).

Assessments of attachment that were developed and validated for middle-

Insecure Attachment and the Social Setting

At first, developmentalists expected secure attachment to “predict all the outcomes reasonably expected from a well-

Harsh contexts, especially the stresses of poverty, reduce the incidence of secure attachment (Seifer et al., 2004; van IJzendoorn & Bakermans-

Securely attached infants are more likely to become secure toddlers, socially competent preschoolers, high-

Although attachment patterns form in infancy (see Table 7.2), they are not necessarily set in stone; they may change when the family context changes, such as abuse or income loss. Many aspects of low SES increase the risk of low school achievement, hostile children, and fearful adults. The underlying premise—

Secure attachment (type B) is more likely if:

|

Insecure attachment is more likely if:

|

Insights from Romania

No scholar doubts that close human relationships should develop in the first year of life and that the lack of such relationships risks dire consequences. Unfortunately, thousands of children born in Romania are proof.

When Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausesçu forbade birth control and abortions in the 1980s, illegal abortions became the leading cause of death for Romanian women aged 15 to 45 (Verona, 2003), and more than 100,000 children were abandoned to crowded, impersonal, state-

In the two years after Ceausesçu was ousted and killed in 1989, thousands of those children were adopted by North American, western European, and Australian families. Those who were adopted before 6 months of age fared best; synchrony was established via play and caregiving. Most of them developed normally.

For those adopted after 6 months, and especially after 12 months, early signs were encouraging: Skinny infants gained weight and grew faster than other 1-

These children are now young adults, many with serious emotional or conduct problems. The cause is more social than biological. Even those who were well nourished, or who caught up to normal growth, often became impulsive and angry teenagers. Apparently, the stresses of adolescence and emerging adulthood have exacerbated the cognitive and social strains on these young people and their families (Merz & McCall, 2011).

Romanian infants are no longer available for international adoption, even though some remain abandoned. Research confirms that early emotional deprivation, not genes or nutrition, is their greatest problem. Romanian infants develop best in their own families, second best in foster families, and worst in institutions (Nelson et al., 2007). As best we know, this applies to infants everywhere: Families usually care for their babies better than strangers who are paid to care for many infants at once.

Fortunately, institutions have improved or been shuttered; more recent adoptees are not as impaired as those Romanian orphans (Merz & McCall, 2011). However, some infants in every nation are deprived of healthy interaction. The early months are a sensitive period for emotional development. Children need responsive parents, biological or not (McCall et al., 2011).

Preventing Problems

All infants need love and stimulation; all seek synchrony and then attachment—

Since synchrony and attachment develop over the first year, and since more than one-

Some birth parents, fearing that they cannot provide responsive parenting, choose adoptive parents for their newborns. If high-

Social Referencing

social referencing Seeking information about how to react to an unfamiliar or ambiguous object or event by observing someone else’s expressions and reactions. That other person becomes a social reference.

Social referencing refers to seeking emotional responses or information from other people, much as a student might consult a dictionary or other reference work. Someone’s reassuring glance or cautionary words; a facial expression of alarm, pleasure, or dismay—

After age 1, when infants can walk and are “little scientists,” their need to consult others becomes urgent. Social referencing is constant, as toddlers search for clues in gazes, faces, and body position, paying close attention to emotions and intentions. They focus on their familiar caregivers, but they also use relatives, other children, and even strangers to help them assess objects and events. They are remarkably selective: Even at 16 months, they notice which strangers are reliable references and which are not (Poulin-

Social referencing has many practical applications. Consider mealtime. Caregivers the world over smack their lips, pretend to taste, and say “yum-

Through this process, some children may develop a taste for raw fish or curried goat or smelly cheese—

Fathers as Social Partners

Fathers enhance their children’s social and emotional development in many ways (Lamb, 2010). Synchrony, attachment, and social referencing are sometimes more apparent with fathers than with mothers. This notion was doubted until research found that some infants are securely attached to their fathers but not to their mothers (Bretherton, 2010). Furthermore, fathers elicit more smiles and laughter from their infants than mothers do, probably because they play more exciting games, while mothers do more caregiving and comforting (Fletcher et al., 2013).

Close father–

BRITTA KASHOLM-

In most cultures and ethnic groups, fathers spend much less time with infants than mothers do (Parke & Buriel, 2006; Tudge, 2008). National cultures and parental attitudes are influential: Some women are gatekeepers, believing that child care is their special domain (Gaertner et al., 2007) and excluding fathers (perhaps indirectly, saying, “You’re not holding her right”). Some fathers think it unmanly to dote on an infant.

That is not equally true everywhere. For example, Denmark has high rates of father involvement. At birth, 97 percent of Danish fathers are present, and five months later, most Danish fathers say that every day they change diapers (83 percent), feed (61 percent), and play with (98 percent) their infants (Munck, 2009).

Less rigid sex roles seem to be developing in every nation. One U.S. example of historical change is the number of married women with children under age 6 who are employed. In 1970, 30 percent of married mothers of young children earned paychecks; in 2012, 60 percent did, almost all in dual-

Note the reference to “married” mothers: About half the mothers of infants in the United States are not married, and their employment rates are higher than their married counterparts. As detailed later in this chapter, often fathers—

One sex difference seems to persist: “Mothers engage in more caregiving and comforting, and fathers in more high intensity play” (Kochanska et al., 2008, p. 41). When asked to play with their baby, mothers typically caress, read, sing, or play traditional games such as peek-

Mothers might say, “Don’t drop him”; fathers and babies laugh with joy. In this way, fathers tend to help children become less fearful. Over the past 20 years, father–

- Can men provide the same care as women?

- Is father–

infant interaction different from mother– infant interaction? - How do fathers and mothers cooperate to provide infant care?

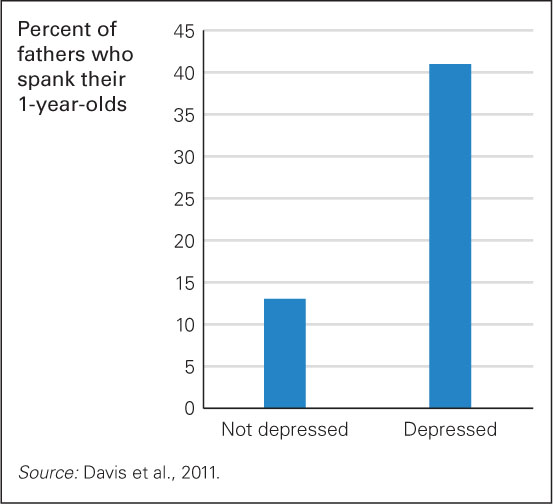

FIGURE 7.2

Shame on Who? Not on the toddlers, who are naturally curious and careless, but maybe not on the fathers either. Both depression and spanking are affected by financial stress, marital conflict, and cultural norms; who is responsible for those?Many studies over the past two decades have answered yes to the first two questions. A baby fed, bathed, and diapered by Dad is just as happy and clean as when Mom does it. Gender differences are sometimes found in specifics, but they are not harmful.

On the third question, the answer depends on the family (Bretherton, 2010). Usually, mothers are caregivers and fathers are playmates, but not always. Each couple, given their circumstances (which might include being immigrant, low-

A constructive parental alliance cannot be assumed, whether or not the parents are legally wed. Sometimes neither parent is happy with their infant, with themselves, or with each other. One study reported that 7 percent of fathers of 1-

Family members affect each other’s moods: Paternal depression correlates with maternal depression and with sad, angry, and disobedient toddlers. Cause and consequence are intertwined. When any one is depressed or hostile, everyone (mother, father, baby) needs help.

SUMMING UP

Caregivers and young infants engage in split-