Injuries and Abuse

Injuries and Abuse

In almost all families of every income, ethnicity, and nation, parents want to protect their children while fostering their growth. Yet more children die from violence—

The contrast between disease and accidental death is most obvious in developed nations, where medical prevention, diagnosis, and treatment make fatal illness rare until late adulthood. In the United States in 2010, almost six times as many 1-

Avoidable Injury

Worldwide, injuries cause millions of premature deaths among adults as well as children: Not until age 40 does any specific disease overtake accidents as a cause of mortality, and 14 percent of all life-

In some nations, malnutrition, malaria, and other infectious diseases combined cause more infant and child deaths than injuries do, but nations with high rates of child disease also have high rates of child injury. India, for example, has one of the highest rates worldwide of child motor-

Age-Related Dangers

Why are 2-

Age-

Injury Control

injury control/harm reduction Practices that are aimed at anticipating, controlling, and preventing dangerous activities; these practices reflect the beliefs that accidents are not random and that injuries can be made less harmful if proper controls are in place.

Instead of using the term accident prevention, public health experts prefer injury control (or harm reduction). Consider the implications. Accident implies that an injury is random, unpredictable; if anyone is at fault, it’s a careless parent or an accident-

A better phrase is injury control, which implies that harm can be minimized with appropriate controls. Minor mishaps (scratches and bruises) are bound to occur, but serious injury is unlikely if a child falls on a safety surface instead of on concrete, if a car seat protects the body in a crash, if a bicycle helmet cracks instead of a skull, or if swallowed pills come from a tiny bottle.

Less than half as many 1-

© DAVID R. FRAZIER/DANITADELIMONT.COM

Prevention

Prevention begins long before any particular child, parent, or legislator does something foolish. Unfortunately, no one notices injuries and deaths that did not happen. For developmentalists, two types of analysis are useful to predict danger and prevent it.

One is called an accident autopsy. Whenever a child is seriously injured, analysis can find causes in the microsystem and exosystem as well as in the macrosystem, and thus protect children in the future. For example, when a child is hit by a car and dies, an autopsy might point not only to parental neglect (microsystem), but also to the lack of parks, speed limits, traffic lights, sidewalks, or curbs (exosystem) or to the fact that the entire nation values fast cars over slow pedestrians (macrosystem).

The second type of analysis involves looking at statistics. For example, the rate of childhood poisoning decreased markedly when pill manufacturers adopted bottles with safety caps that are difficult for 2-

Levels of Prevention

Three levels of prevention apply to every health and safety issue.

- In primary prevention, the overall situation is structured to make harm less likely. Primary prevention fosters conditions that reduce everyone’s chance of injury.

primary prevention Actions that change overall background conditions to prevent some unwanted event or circumstance, such as injury, disease, or abuse.

- Secondary prevention is more specific, averting harm in high-

secondary prevention Actions that avert harm in a high-

risk situation, such as stopping a car before it hits a pedestrian. risk situations or for vulnerable individuals. - Tertiary prevention begins after an injury has already occurred, limiting damage.

tertiary prevention Actions, such as immediate and effective medical treatment, that are taken after an adverse event (such as illness or injury) and that are aimed at reducing harm or preventing disability.

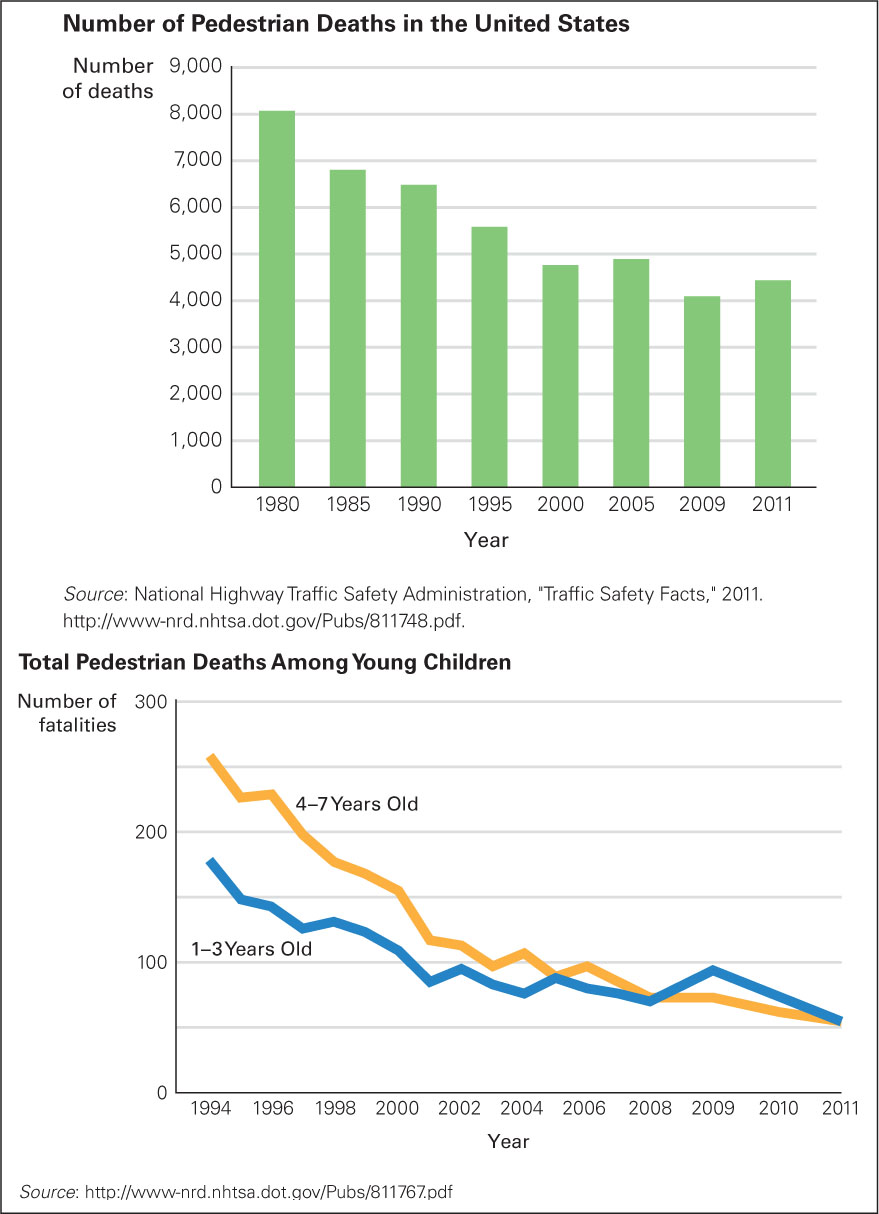

In general, tertiary prevention is the most visible of the three levels, but primary prevention is the most effective (Cohen et al., 2010). An example comes from data on pedestrian deaths. Fewer people in the United States die after being hit by a motor vehicle than did 35 years ago (see Figure 8.6). How does each level of prevention contribute?

FIGURE 8.6

While the Population Grew This chart shows dramatic evidence that prevention measures are succeeding in the United States. Over the same time period, the total population has increased by about one-Especially for Urban Planners Describe a neighborhood park that would benefit 2-

Response for Urban Planners: The adult idea of a park—

Primary prevention includes sidewalks, speed bumps, pedestrian overpasses, streetlights, and traffic circles. Cars have been redesigned (e.g., better headlights, windows, and brakes), and drivers’ competence has improved (e.g., with stronger drunk-

Secondary prevention reduces danger in high-

Finally, tertiary prevention reduces damage after an accident. Examples include laws against hit-

Child Maltreatment

Until about 1960, people thought child maltreatment was rare and consisted of a sudden attack by a disturbed stranger. Today we know better, thanks to a pioneering study based on careful observation in one Boston hospital (Kempe & Kempe, 1978). Maltreatment is neither rare nor sudden, and the perpetrators are usually one or both of the child’s own parents. That makes it much worse: Ongoing maltreatment, with no protector, is much more damaging than a single incident, however injurious.

Definitions and Statistics

child maltreatment Intentional harm to or avoidable endangerment of anyone under 18 years of age.

child abuse Deliberate action that is harmful to a child’s physical, emotional, or sexual well-

child neglect Failure to meet a child’s basic physical, educational, or emotional needs.

Child maltreatment now refers to all intentional harm to, or avoidable endangerment of, anyone under 18 years of age. Thus, child maltreatment includes both child abuse, which is deliberate action that is harmful to a child’s physical, emotional, or sexual well-

The more that researchers study the long-

substantiated maltreatment Harm or endangerment that has been reported, investigated, and verified.

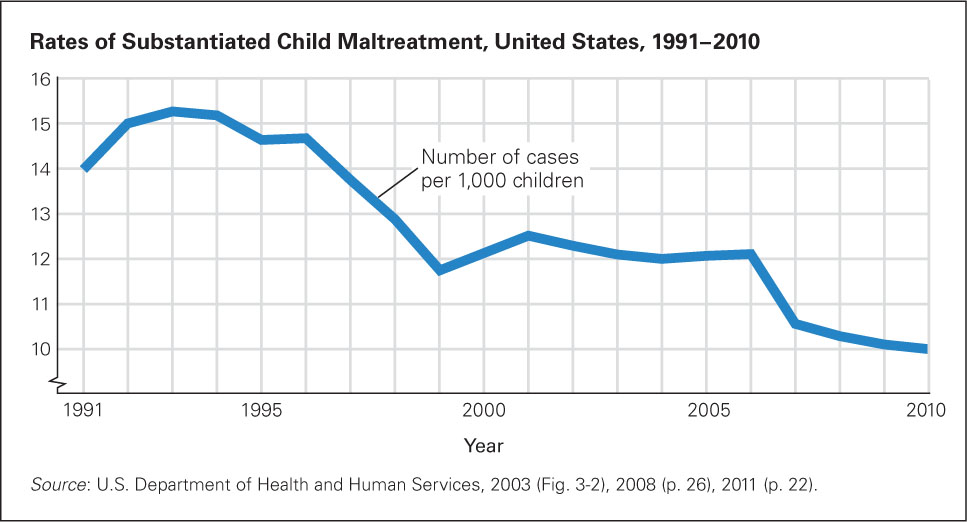

Substantiated maltreatment means that a case has been reported, investigated, and verified (see Figure 8.7). The U.S. rate was about 700,000 in 2011; almost 200,000 of these incidents occurred during the victims’ preschool years. Annually about 1 in every 90 young children, aged 2 to 5 years old, is substantiated as a maltreatment victim.

Observation Quiz The data point for 2010 is close to the bottom of the graph. Does that mean it is close to zero?

Answer to Observation Quiz: No. The number is actually 10.0 per 1,000. Note the little squiggle on the graph’s vertical axis below the number 10. This means that numbers between 0 and 9 are not shown.

FIGURE 8.7

Still Far Too Many The number of substantiated cases of maltreatment of children under age 18 in the United States is too high, but there is some good news: The rate has declined significantly from its peak in 1993.reported maltreatment Harm or endangerment about which someone has notified the authorities.

Reported maltreatment means simply that the authorities have been informed. Since 1993, the number of children reported as maltreated in the United States has ranged from about 2.7 million to 3.6 million per year.

The three-

- Each child is counted only once. Thus, five verified reports about a single child can result in one substantiated case.

- Substantiation requires proof. Not every investigation finds unmistakable injuries, severe malnutrition, or a witness willing to testify.

- Many professionals are mandated reporters, required to report any signs of possible maltreatment. Some signs are caused by something that could be maltreatment, but investigation finds another cause (Pietrantonio et al., 2013).

- A report may be false or deliberately misleading (though few are) (Kohl et al., 2009).

Especially for Nurses While weighing a 4-

Response for Nurses: Any suspicion of child maltreatment must be reported, and these bruises are suspicious. Someone in authority must find out what is happening so that the parent as well as the child can be helped.

Frequency of Maltreatment

How often does maltreatment actually occur? No one knows. Not all cases are noticed; not all that are noticed are reported; and not all reports are substantiated. Similar issues apply in every nation, city, and town, with marked variations in reports and confirmations.

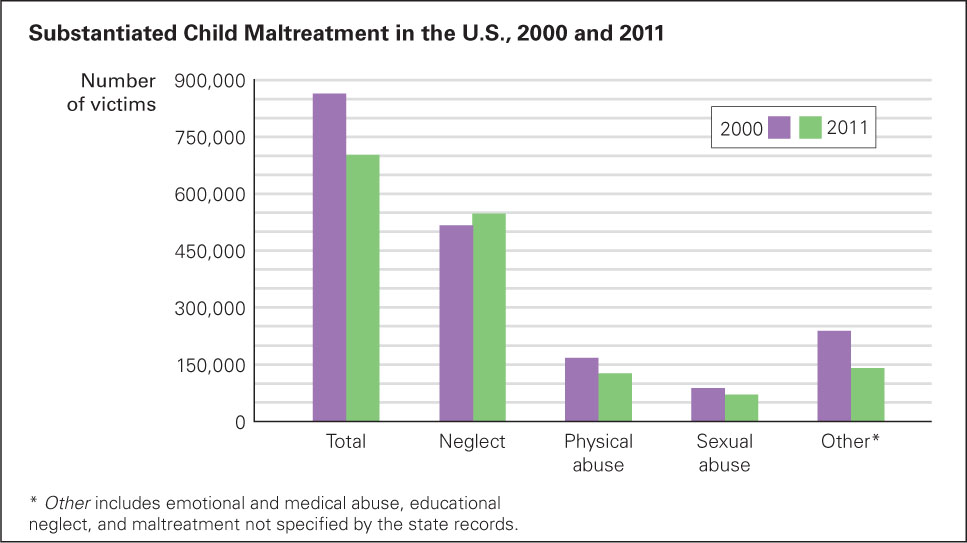

If we rely on official U.S. statistics, interesting trends are apparent. Officially, substantiated child maltreatment increased from about 1960 to 1990 but decreased thereafter (see Figure 8.8). Physical and sexual abuse declined but neglect did not. Other sources also report declines over the past two decades. That seems to be good news; perhaps national awareness of child abuse led to better reporting and then better prevention.

FIGURE 8.8

Getting Better? As you can see, the number of victims of child maltreatment in the United States has declined in the past decade. The legal and social-Unfortunately official reports leave room for doubt. For example, Pennsylvania and Maine reported almost identical numbers of substantiated victims in 2010 (3,388 and 3,270, respectively), but the child population of Pennsylvania is ten times that of Maine. No one thinks that Maine children suffer ten times more than Pennsylvania children; something in reporting or substantiating must differ between those two states. Whether or not maltreatment is reported is powerfully influenced by culture (one of my students asked, “When is a child too old to be beaten?”) and by personal willingness to report. The United States has become more culturally diverse; could that be why reports are down?

Observation Quiz Have all types of maltreatment declined since 2000?

Answer to Observation Quiz Most types of abuse are declining, but not neglect. This kind of maltreatment may be the most harmful because the psychological wounds last for decades.

In a confidential nationwide survey of young adults in the United States, 1 in 4 said they had been physically abused (“slapped, hit, or kicked” by a parent or other adult caregiver) before sixth grade, and 1 in 22 had been sexually abused (“touched or forced to touch someone else in a sexual way”) (Hussey et al., 2006). Almost never had their abuse been reported. The authors of this study think these rates are underestimates (Hussey et al., 2006)!

One reason for these high rates may be that the respondents were asked if they had ever been mistreated by someone who was caring for them; most other sources report annual rates. Another reason is that few children report their own abuse. Indeed, many children do not realize that they are mistreated until later, when they compare their experiences with those of their friends. Even then, some adults who were slapped, hit, or kicked in childhood do not think they were abused.

Warning Signs

Often the first sign of maltreatment is delayed development, such as slow growth, immature communication, lack of curiosity, or unusual social interactions. All these difficulties may be evident even at age 1 (Valentino et al., 2006).

post-

During early childhood, maltreated children may seem fearful, startled by noise, defensive and quick to attack, and confused between fantasy and reality. These are symptoms of post-

Consequences of Maltreatment

The impact of any child-

| Injuries that are unlikely to be accidents, such as bruises on both sides of the face or body; burns with a clear line between burned and unburned skin |

| Repeated injuries, especially broken bones not properly tended (visible on X- |

| Fantasy play, with dominant themes of violence or sex |

| Slow physical growth |

| Unusual appetite or lack of appetite |

| Ongoing physical complaints, such as stomachaches, headaches, genital pain, sleepiness |

| Reluctance to talk, to play, or to move, especially if development is slow |

| No close friendships; hostility toward others; bullying of smaller children |

| Hypervigilance, with quick, impulsive reactions, such as cringing, startling, or hitting |

| Frequent absence from school |

| Frequent change of address |

| Frequent change in caregivers |

| Child seems fearful, not joyful, on seeing caregiver |

The biological and academic impairment resulting from maltreatment is substantial and thus relatively easy to notice, as when a teacher sees when a child is bruised, broken, shivering, or failing. However, when researchers follow maltreated children over the years, enduring deficits in social skills usually seem more crippling than physical damages. Some research finds that maltreated children tend to hate themselves, and then hate everyone else, with effects still evident in adulthood (Sperry & Widom, 2013).

Hate is corrosive. A warm and enduring friendship might repair some of the damage, but maltreatment itself makes such a friendship unlikely. Many studies have found that mistreated children typically regard other people as hostile and exploitative; hence, abused children are less friendly, more aggressive, and more isolated than other children. The earlier the abuse starts and the longer it continues, the worse their peer relationships are (Scannapieco & Connell-

Deficits are lifelong. Maltreated children may become bullies or victims or both, not only in childhood and adolescence but also in adulthood. They tend to dissociate, that is, to disconnect their memories from their understanding of themselves (Valentino et al., 2008). Adults who were severely maltreated as children (physically, sexually, or emotionally) often abuse drugs or alcohol, enter unsupportive relationships, become victims or aggressors, sabotage their own careers, eat too much or too little, and engage in other self-

In the current economic climate, finding and keeping a job is a critical aspect of adult well-

This study is just one of hundreds of longitudinal studies, all of which find that maltreatment affects children decades after the broken bones, or skinny bodies, or medical neglect disappear. To protect the health of the entire society in the future, we need to stop maltreatment now.

Three Levels of Prevention, Again

Just as with injury control, the ultimate goal with regard to child maltreatment is primary prevention, in which a changed social context makes parents and neighbors more likely to protect every child. Neighborhood stability, parental education, income support, and fewer unwanted children all reduce the rate of maltreatment.

Secondary prevention involves spotting warning signs and intervening to keep a risky situation from getting worse (Giardino & Alexander, 2011). For example, insecure attachment, especially of the disorganized type, is a sign of a disrupted parent–

Maltreatment is reduced by home visits from helpful nurses or social workers and by high-

Tertiary prevention is geared to the limitation of harm after maltreatment has occurred. Reporting and substantiating abuse are the first steps. Often the caregiver needs help in providing better care. Sometimes the child needs another home. If hospitalization is required, that signifies failure: Intervention should have begun much earlier. At that point, treatment is very expensive, harm has already been done, and hospitalization itself further strains the parent–

permanency planning An effort by child-

Children need caregivers they trust, in safe and stable homes, whether they live with their biological parents, a foster family, or an adoptive family. Whenever a child is removed from an abusive or neglectful home, permanency planning must begin, through which a family is found to nurture the child until adulthood.

This requires cooperation among social workers, judges, and psychologists as well as the caregivers themselves (Edwards, 2007). Sometimes the child’s original family can become better caregivers; sometimes a relative can be found who will provide good care; sometimes a stranger is the best caregiver.

Similar problems arise for homeless children, who often not only move from place to place but also move in and out of the foster care system (Zlotnick et al., 2012). The best ways to help such children are not obvious, as research-

foster care A legal, publicly supported system in which a maltreated child is removed from the parents’ custody and entrusted to another adult or family, which is reimbursed for expenses incurred in meeting the child’s needs.

kinship care A form of foster care in which a relative of a maltreated child, usually a grandparent, becomes the approved caregiver.

In foster care, children are officially taken from their parents and entrusted to another adult or family; foster parents are reimbursed for the expenses they incur in meeting the children’s needs. In every year from 2000 to 2011, about half a million children in the United States were in foster care. More than half of them were in a special version of foster care called kinship care, in which a relative—

In every nation, most foster children are from low-

Adequate support is not typical, however. One obvious failing is that many children move from one foster home to another for reasons that are unrelated to the child’s behavior or wishes (Jones & Morris, 2012). Each move increases the risk of a poor outcome (Oosterman et al., 2007). Another problem is that kinship care is sometimes used as an easy, less expensive solution. Kinship care may be better than stranger care, but supportive services are especially needed since the grandparent who gets the child is also the parent of the abusive adult (Edwards, 2010; Fechter-

adoption A legal proceeding in which an adult or couple is granted the joys and obligations of being that child’s parent(s).

Adoption (when an adult or couple is legally granted parenthood) is the best permanent option when a child should not be returned to a parent. However, adoption is difficult for many reasons, among the following:

- Judges and biological parents are reluctant to release children for adoption.

- Most adoptive parents prefer infants.

- Some agencies screen out families not headed by a heterosexual married couple.

- Some professionals insist that adoptive parents be of the same ethnicity and religion as the child.

- Some adults who want to adopt are not ready for the responsibilities entailed.

As detailed many times in this chapter, caring for young children is not easy, whether it involves making them brush their teeth or keeping them safe from harm. Parents shoulder most of the burden, and their love and protection usually result in strong and happy children. Teachers can be crucial during these years, working closely with the parents. Beyond the microsystem, however, complications abound. Parents and teachers are failing with at least a million young children in the United States. The benefit to the entire community of well-

SUMMING UP

As they move with more speed and agility, young children encounter new dangers. Compared to older children, they are more often injured, abused, or neglected. Maltreatment has lifelong consequences, with neglect often worse than abuse, and social and emotional deficits harder to remedy that physical harm.

Overall in the United States, official rates of substantiated maltreatment have decreased in the past 25 years but more needs to be done. In primary prevention, laws and customs need to protect everyone; in secondary prevention, supervision, forethought, and protective care can prevent harm to those at risk. When injury or maltreatment occurs, quick and effective medical and psychosocial intervention is needed (tertiary prevention). Foster care and adoption are sometimes best for children, but these options are not as available as they need to be. Putting an end to maltreatment of all kinds is urgent but complex because changes are needed in families, cultures, communities, and laws.