Thinking During Early Childhood

Thinking During Early Childhood

You have just learned that every year of early childhood advances motor skills, brain development, and impulse control. Each of these affects cognition, as first described by Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky, already mentioned in Chapter 1.

Piaget: Preoperational Thought

preoperational intelligence Piaget’s term for cognitive development between the ages of about 2 and 6; it includes language and imagination (which involve symbolic thought), but logical, operational thinking is not yet possible at this stage.

Early childhood is the time of preoperational intelligence, the second of Piaget’s four periods of cognitive development. He called early-

symbolic thought A major accomplishment of preoperational intelligence that allows a child to think symbolically, including understanding that words can refer to things not seen and that an item, such as a flag, can symbolize something else (in this case, for instance, a country).

However, preoperational children are past sensorimotor intelligence because they can think in symbols, not just via senses and motor skills. In symbolic thought, an object or word can stand for something else, including something not seen, or pretended. That is more advanced than thinking only via the senses, because using words makes it possible to think about many more things at once. However, although vocabulary and imagination can soar, logical connections between ideas are not yet active, not yet operational.

The word dog, for instance, is at first only the family dog sniffing at the child, not yet a symbol (Callaghan, 2013). By age 2, the word becomes a symbol: It can refer to a remembered dog, or a plastic dog, or an imagined dog. Symbolic thought allows for the language explosion (detailed later in this chapter), which enables children to talk about thoughts and memories. However, since thought is preoperational, it is hard for young children to understand the historical connections, similarities, and differences between dogs and wolves, or even between a cocker spaniel and a collie.

animism The belief that natural objects and phenomena are alive.

Symbolic thought helps explain animism, the belief of many young children that natural objects (such as a tree or a cloud) are alive and that nonhuman animals have the same characteristics as the child. Many children’s stories include animals or objects that talk and listen (Aesop’s fables, Winnie-

Obstacles to Logic

Piaget described symbolic thought as characteristic of preoperational thought. He also described four limitations that make logic difficult until about age 6: centration, focus on appearance, static reasoning, and irreversibility.

centration A characteristic of preoperational thought in which a young child focuses (centers) on one idea, excluding all others.

Centration is the tendency to focus on one aspect of a situation to the exclusion of all others. Young children may, for example, insist that Daddy is a father, not a brother, because they center on the role that he fills for them.

egocentrism Piaget’s term for children’s tendency to think about the world entirely from their own personal perspective.

The daddy example illustrates a particular type of centration that Piaget called egocentrism—literally, “self-

Egocentrism is not selfishness, however. One 3-

focus on appearance A characteristic of preoperational thought in which a young child ignores all attributes that are not apparent.

A second characteristic of preoperational thought is a focus on appearance to the exclusion of other attributes. For instance, a girl given a short haircut might worry that she has turned into a boy. In preoperational thought, a thing is whatever it appears to be—

static reasoning A characteristic of preoperational thought in which a young child thinks that nothing changes. Whatever is now has always been and always will be.

Third, preoperational children use static reasoning, believing that the world is unchanging, always in the state in which they currently encounter it. Many children cannot imagine that their own parents were ever children. If they are told that Grandma is their mother’s mother, they still do not understand how people change with maturation. One preschooler wanted his grandmother to tell his mother to never spank him because “she has to do what her mother says.”

irreversibility A characteristic of preoperational thought in which a young child thinks that nothing can be undone. A thing cannot be restored to the way it was before a change occurred.

The fourth characteristic of preoperational thought is irreversibility. Preoperational thinkers fail to recognize that reversing a process sometimes restores whatever existed before. A young girl might cry because her mother put lettuce on her sandwich. Overwhelmed by her desire to have things “just right,” she might reject the food even after the lettuce is removed because she believes that what is done cannot be undone.

A CASE TO STUDY

Stones in the Belly

As we were reading a book about dinosaurs, 3-

I was amazed, never having known this before.

“I didn’t know that dinosaurs ate stones,” I said.

‘They don’t eat them.”

‘Then how do they get the stones in their bellies? They must swallow them.”

“They don’t eat them.”

“Then how do they get in their bellies?”

“They are just there.”

“How did they get there?”

“They don’t eat them,” said Caleb. “Stones are dirty. We don’t eat them.”

I dropped it, but my question apparently puzzled him. Later he asked his mother, “Do dinosaurs eat stones?”

“Yes, they eat stones so they can grind their food,” she answered.

At that, Caleb was quiet.

In all of this, preschool cognition is evident. Caleb’s vocabulary is impressive, although he uses the word belly for stomach, since belly is easier for children to say. He can name several kinds of dinosaurs, as can many young children. He also shares with many other children a fascination with defecation and large animals, topics no longer intriguing to adults.

But logic eludes Caleb, as it does most young children. It seems obvious that dinosaurs must somehow have gotten the stones into their bellies. However, in his static thinking, Caleb said the stones “were just there.” In his typical egocentrism, he rejects the thought that they ate them, because he knows that stones are too dirty for him to eat. Should I have expected him to tell me that I was right, when his mother agreed with me?

Conservation and Logic

conservation The principle that the amount of a substance remains the same (i.e., is conserved) even when its appearance changes.

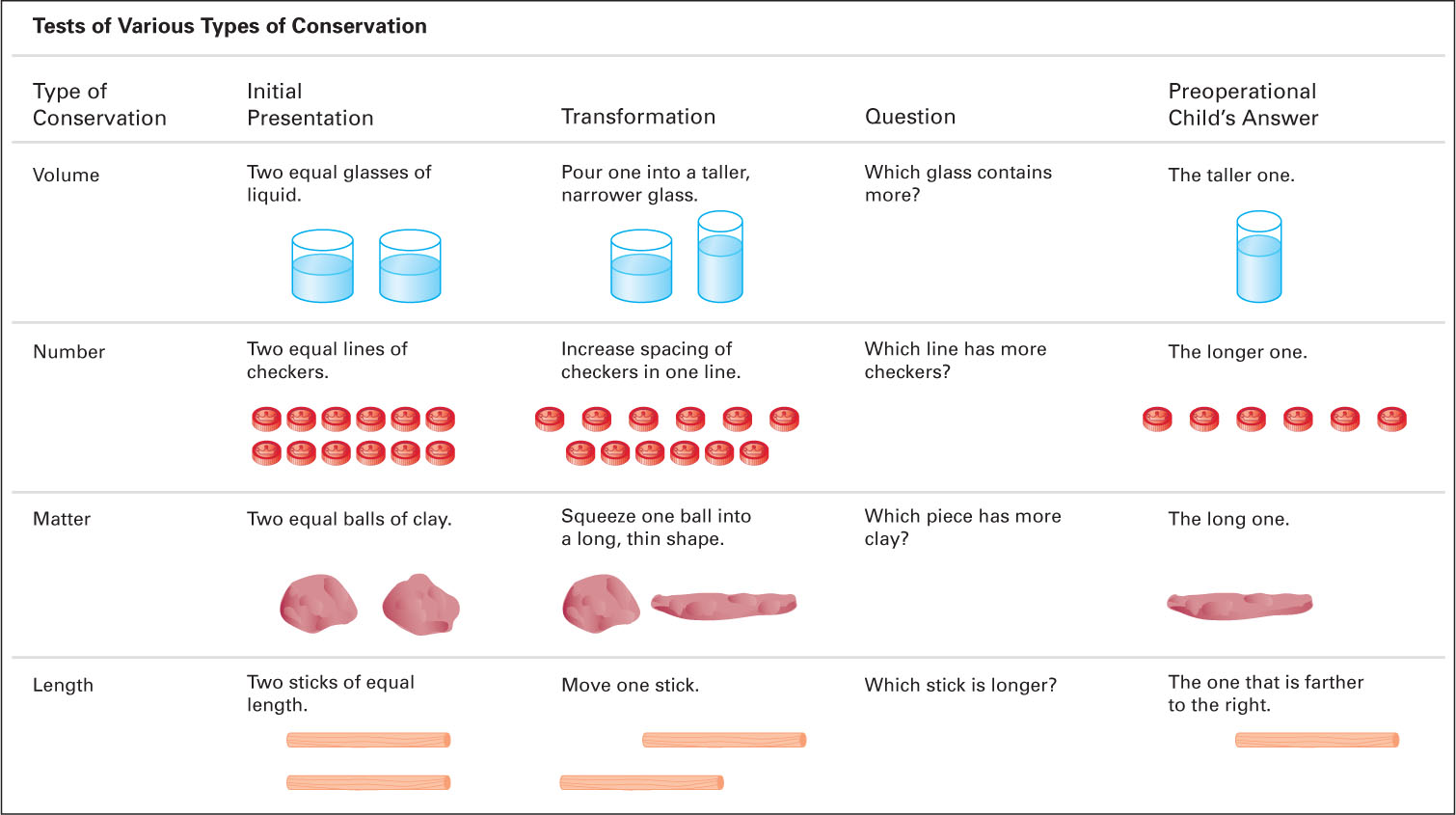

Piaget highlighted several ways in which preoperational intelligence disregards logic. A famous set of experiments involved conservation, the notion that the amount of something remains the same (is conserved) despite changes in its appearance.

Suppose two identical glasses contain the same amount of pink lemonade, and the liquid from one of these glasses is poured into a taller, narrower glass. If young children are asked whether one glass contains more or both glasses contain the same amount, they will insist that the narrower glass (with the higher level) has more. (See Figure 9.1 for other examples.)

FIGURE 9.1

Conservation, Please According to Piaget, until children grasp the concept of conservation at (he believed) about age 6 or 7, they cannot understand that the transformations shown here do not change the total amount of liquid, checkers, clay, and wood.Especially for Nutritionists How can Piaget’s theory help you encourage children to eat healthy foods?

Response for Nutritionists: Take each of the four characteristics of preoperational thought into account. Because of egocentrism, having a special place and plate might assure the child that this food is exclusively his or hers. Since appearance is important, food should look tasty. Since static thinking dominates, if something healthy is added (e.g., grate carrots into the cake, add milk to the soup), do it before the food is given to the child. In the reversibility example in the text, the lettuce should be removed out of the child’s sight and the “new” hamburger presented.

All four characteristics of preoperational thought are evident in this mistake. Young children fail to understand conservation because they focus (center) on what they see (appearance), noticing only the immediate (static) condition. It does not occur to them that they could reverse the process and re-

Piaget’s original tests of conservation required children to respond verbally to an adult’s questions. Later research has found that when the tests of logic are simplified or made playful, young children may succeed. In many ways, children indicate via eye movements or gestures that they know something before they can say it in words (Goldin-

As with sensorimotor intelligence in infancy, Piaget underestimated what preoperational children could understand. Piaget was right that young children are not as logical as older children, but he did not realize how much they could learn.

Brain scans, videos measured in milliseconds, and the computer programs that developmentalists now use were not available to him. Studies from the past 20 years show intellectual activity before age 6 that was not previously known, although they also show that Piaget was perceptive about many aspects of cognition (Crone & Ridderinkhof, 2011).

Given the new data, it is easy to be critical of Piaget. However, note that many adults make the same mistakes as children. For instance, the shape of boxes and bottles in the grocery store undermine adults’ sense of conservation (package designers know that an ounce does not always appear to be an ounce). Animism is evident in many religious and cultural myths that include talking, thinking animals.

Indeed, most adults encourage children to believe in Santa Claus, the Tooth Fairy, and so on (Barrett, 2008). If preschoolers are foolish to imagine that animals and plants have human traits, what are adults who talk to their pets and who mourn the death of a tree? And why do some adults take it personally when it rains unexpectedly?

Vygotsky: Social Learning

For decades, the magical, illogical, and self-

Vygotsky emphasized another side of early cognition—

Mentors

Vygotsky believed that cognitive development is embedded in a social context at every age (Vygotsky, 1934/1987). He stressed that children are curious and observant. They ask questions—

As you remember from Chapter 2, children learn through guided participation, as mentors teach them. Parents are the first guides, although children are guided by many others too. For example, the verbal proficiency of children in day-

Observation Quiz What three sociocultural factors make it likely that the child pictured to the left will learn?

Answer to Observation Quiz: Motivation (this father and son are from Spain, where yellow running shoes are popular); human relationships (note the physical touching of father and son); and materials (the long laces make tying them easier).

According to Vygotsky, children learn because their mentors do the following:

- Present challenges.

- Offer assistance (without taking over).

- Add crucial information.

- Encourage motivation.

Overall, the ability to learn from mentors indicates intelligence; according to Vygotsky: “What children can do with the assistance of others might be in some sense even more indicative of their mental development than what they can do alone” (1934/1987, p. 5).

Scaffolding

zone of proximal development (ZPD) Vygotsky’s term for the skills—

scaffolding Temporary support that is tailored to a learner’s needs and abilities and aimed at helping the learner master the next task in a given learning process.

Vygotsky believed that all individuals learn within their zone of proximal development (ZPD), an intellectual arena in which new ideas and skills can be mastered. Proximal means “near,” so the ZPD includes the ideas children are close to understanding as well as the skills they can almost master but are not yet able to demonstrate independently. How and when children learn depends, in part, on the wisdom and willingness of mentors to provide scaffolding, or temporary sensitive support, to help them within their developmental zone.

Good mentors provide plenty of scaffolding, encouraging children to look both ways before crossing the street (while holding the child’s hand) or letting them stir the cake batter (perhaps while covering the child’s hand on the spoon handle, in guided participation).

Observation Quiz Is the girl in the picture right-

Answer to Observation Quiz: Right-

Sometimes scaffolding is inadvertent, as when children observe something said or done and then try to do likewise—

overimitation When a person imitates an action that is not a relevant part of the behavior to be learned. Overimitation is common among 2-

More benignly, children imitate habits and customs that are meaningless, a trait called overimitation, evident in humans but not in other animals. This stems from the child’s eagerness to learn from mentors, allowing “rapid, high-

Overimitation was demonstrated in an experiment with 2-

One by one, all the Australian and half of the Bushman children observed an adult perform irrelevant actions, such as waving a red stick above a box three times and then using that stick to push down a knob to open the box, which could be easily and more efficiently opened by merely pulling down the same knob by hand. Then children were given the stick and the box. No matter what their cultural background, the children followed the adult example, waving the stick three times and not using their hands directly on the knob.

Other Bushman children did not see the demonstration. When they were given the stick and asked to open the box, they simply pulled the knob. Then they observed an adult do the stick-

Especially for Driving Instructors Sometimes your students cry, curse, or quit. How would Vygotsky advise you to proceed?

Response for Driving Instructors: Use guided participation to scaffold the instruction so that your students are not overwhelmed. Be sure to provide lots of praise and days of practice. If emotion erupts, do not take it as an attack on you.

Apparently, children everywhere learn from others through observation, even if they have not been taught to do so. They even learn to do things contrary to their prior learning. Thus, scaffolding occurs through observation as well as explicit guidance. Across cultures, “similarity of performance is profound” (Nielsen & Tomaselli, 2010, p. 734), with children everywhere strongly inclined to learn whatever adults from their culture do. That is exactly what Vygotsky explained.

As always, cultural differences are crucial. Consider book-

By contrast, book-

© ARABIANEYE/CORBIS

Words, Cultures, and Math

Vygotsky particularly stressed the role of language to advance thought. He wrote that private speech, which is talking to oneself either out loud or in one’s mind, is an important road to cognitive development. That seems to be especially true in early childhood (Al-

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

Research Report: Early Childhood and STEM

A practical use of Vygotsky’s theory concerns the current emphasis on STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math) education. Because finding more young people to specialize in those fields is crucial for economic growth, educators and political leaders are continually seeking ways to make STEM fields attractive to adolescents and young adults of all ethnicities (Rogers-

Research on early childhood suggests that STEM education actually begins long before high school. This is increasingly recognized by experts, who note that most parents and teachers have much to learn about math and science if they wish to teach these subjects to young children (Hong et al., 2013; Bers et al., 2013)

For example, learning about numbers is possible very early in life. Even babies have a sense of whether one, two, or three objects are in a display, although exactly what infants understand about numbers is controversial (Varga et al., 2010). If Vygotsky is correct that words are tools, toddlers need to hear number words and science concepts (not just counting and shapes, but fractions and science principles, such as the laws of motion) early so that other knowledge becomes accessible. In math understanding, it is evident that preschoolers gradually learn to:

- Count objects, with one number per item (called one-

to- ).one correspondence - Remember times and ages (bedtime at 8, a child is 4 years old, and so on).

- Understand sequence (first child wins, last child loses).

- Know what numbers are higher than others (it is not obvious to young children that 7 is more than 4).

These and many other cognitive accomplishments of young children have been the subject of extensive research: Mentoring and language are always found to be pivotal.

Culture affects language and may foster math knowledge. For example, English-

German-

By age 3 or 4, children’s brains are mature enough to comprehend numbers, store memories, and recognize routines. Whether or not children actually demonstrate such understanding depends on what they hear and how they participate in various activities within their families, schools, and cultures.

Some 2-

Children’s Theories

Piaget and Vygotsky both recognized that children work to understand their world. No contemporary developmental scientist doubts that. How do children acquire their impressive knowledge? Part of the answer is that children do more than gain words and concepts—

Theory-Theory

theory-

Humans of all ages want explanations. Theory-

search for causal regularities in the world around us. We are perpetually driven to look for deeper explanations of our experience, and broader and more reliable predictions about it … Children seem, quite literally, to be born with … the desire to understand the world and the desire to discover how to behave in it.

[Gopnik, 2001, p. 66]

According to theory-

Exactly how do children seek explanations? They ask questions, and, if they are not satisfied with the answers, they develop their own theories. This is particularly evident in children’s understanding of God and religion. One child thought his grandpa died because God was lonely; another thought thunder occurred because God was rearranging the furniture.

Theories do not appear randomly. Children wonder about the underlying purpose of whatever they observe, and they note how often a particular event occurs in order to develop a theory about what causes what and why (Gopnik & Wellman, 2012). Of course, their theories are not always correct.

For instance, when I was a young child, I noticed that my father never carried an umbrella. Since I looked up to him, I assumed he must have had a good reason. Consequently, throughout all my adult years, I never carried an umbrella. Neither did my brother, which confirmed for me that my father was right.

Over time I developed many reasons for my father’s behavior. He must have realized, I decided, that umbrellas poke people in the eye, get forgotten, blow away, and are lost. Then, when Dad was in his 80s, my brother asked him why he didn’t like umbrellas. The answer was “Chamberlain.” Neville Chamberlain was famous for carrying an umbrella when he was prime minister of England from 1937 to 1940; and he was photographed with his black umbrella after signing the Munich Agreement in 1938, when he announced that Hitler would not attack England. For Dad, umbrellas symbolized foolish trust. All my theories were imagined to justify something I did not understand. That is theory-

A series of experiments that explored when and how 3-

Indeed, even when asked to repeat something ungrammatical that an adult says, children often correct the grammar. They theorize that the adult intended to speak grammatically but failed to do so (Over & Gattis, 2010). This is another example of a general principle: Children develop theories about intentions before they employ their impressive ability to imitate; they do not mindlessly copy whatever they observe. As you have read, when children saw an adult wave a stick before opening a box, the children theorized that, since the adult did it deliberately, stick-

Theory of Mind

Mental processes—

theory of mind A person’s theory of what other people might be thinking. In order to have a theory of mind, children must realize that other people are not necessarily thinking the same thoughts that they themselves are. That realization seldom occurs before age 4.

To know what goes on in another’s mind, people develop a folk psychology, which includes ideas about other people’s thinking, called theory of mind. Theory of mind is an emergent ability, slow to develop but typically beginning in most children at about age 4 (Sterck & Begeer, 2010).

Realizing that thoughts do not mirror reality is beyond very young children, but that realization dawns on them sometime after age 3. It then occurs to them that people can be deliberately deceived or fooled—

Especially for Social Scientists Can you think of any connection between Piaget’s theory of preoperational thought and 3-

Response for Social Scientists: According to Piaget, preschool children focus on appearance and on static conditions (so they cannot mentally reverse a process). Furthermore, they are egocentric, believing that everyone shares their point of view. No wonder they believe that they had always known the puppy was in the blue box and that Max would know that, too.

In one of several false-

Indeed, 3-

The development of theory of mind can be seen when young children try to escape punishment by lying. Their face often betrays them: worried or shifting eyes, pursed lips, and so on. Parents sometimes say, “I know when you are lying,” and, to the consternation of most 3-

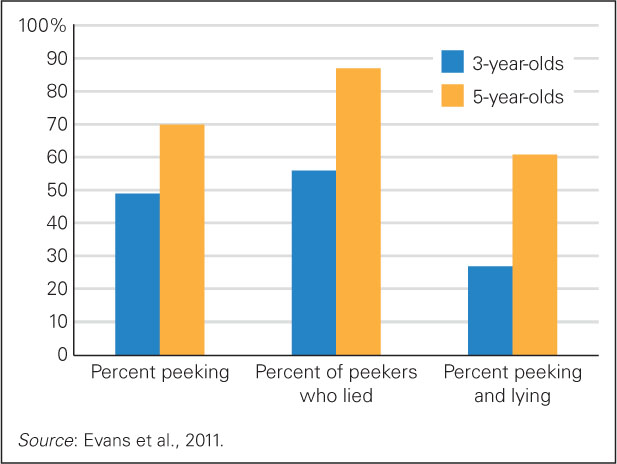

In one experiment, 247 children, aged 3 to 5, were left alone at a table that had an upside-

The rest lied, with increasing skill. The 3-

This particular study was done in Beijing, China, but the results seem universal: Older children are better liars. Beyond the age differences, the experimenters found that the more logical liars were also more advanced in theory of mind and executive functioning (Evans et al., 2011), which indicates a more mature prefrontal cortex (see Figure 9.2).

FIGURE 9.2

Better with Age? Could an obedient and honest 3-Brain and Context

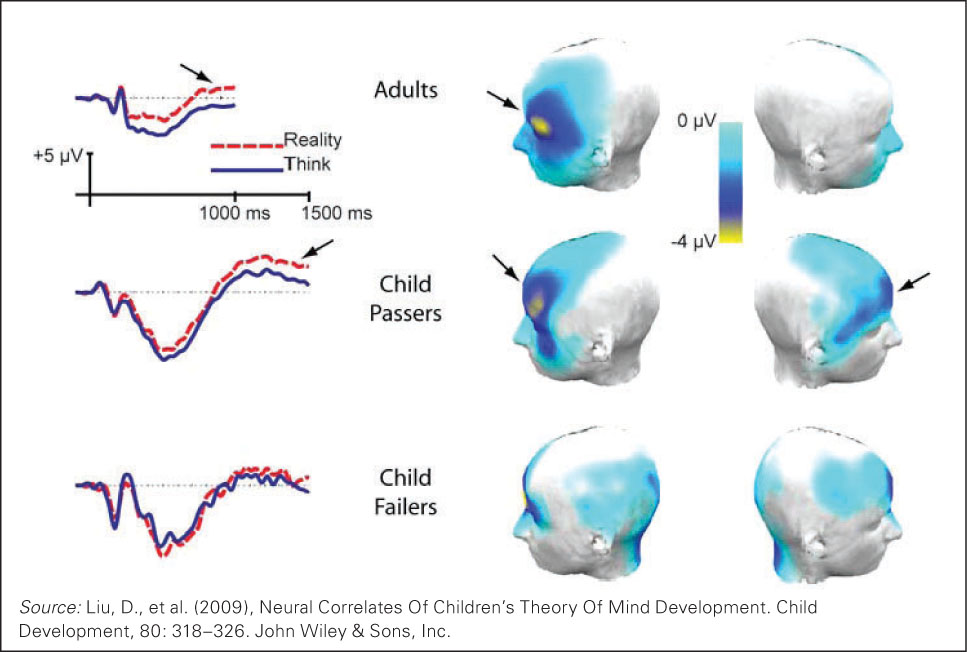

Many studies have found that a child’s ability to develop theories correlates with the maturity of the prefrontal cortex and with advances in executive processing (Mar, 2011). This brain connection was further suggested by research on 8-

Additional evidence for the crucial role of the prefrontal cortex in development of theory of mind comes from the other study of 3-

FIGURE 9.3

Brains at Work Neuroscience confirms the critical role of the prefrontal cortex in development of theory of mind. Adults and 4-Does the crucial role of brain maturation make context irrelevant? No (Sterck & Begeer, 2010); nurture is always important. For instance, research finds that language development fosters theory of mind, especially when mother—

As brothers and sisters argue, agree, compete, and cooperate, and as older siblings fool younger ones, it dawns on 3-

Finally, the exosystem also influences development of theory of mind. A meta-

SUMMING UP

Preoperational children, according to Piaget, can use symbolic thought but are illogical and egocentric, limited by appearance and immediate experience. Their egocentrism occurs not because they are selfish, but because their minds are immature. Vygotsky realized that children are powerfully influenced by their social contexts, including their mentors and the cultures in which they live. In their zone of proximal development, children are ready to move beyond their current understanding, especially if deliberate or inadvertent scaffolding occurs.

Children use their cognitive abilities to develop theories about their experiences, as is evident in theory-