1a. Assessing the writing situation

Begin by taking a look at your writing situation. The key elements of a writing situation include the following:

- subject

- purpose

- audience

- genre

- sources of information

- constraints (length, document design, reviewers, deadlines)

It is likely that you will make final decisions about all of these matters later in the writing process—after a first draft, for example—but you can save yourself time by thinking about as many of them as possible in advance. For a quick checklist, see the chart "Checklist for assessing the writing situation" at the bottom of the page.

Subject

Frequently your subject will be given to you. In a psychology class, for example, you might be asked to explain Bruno Bettelheim’s Freudian analysis of fairy tales. In a composition course, assignments often ask you to analyze texts and evaluate arguments. In the business world, you may be assigned to draft a marketing plan. When you are free to choose your own subject, let your own curiosity focus your choice. If you are studying television, radio, and the Internet in a communications course, for example, you might ask yourself which of these subjects interests you most. Perhaps you want to learn more about the role streaming video can play in activism and social change. Look through your readings and class notes to see if you can identify questions you’d like to explore further in an essay.

Make sure that you can reasonably investigate your subject in the space you have. If you are limited to a few pages, for example, you could not do justice to a broad subject such as “videos as agents of social change.” You could, however, focus on one aspect of the subject—perhaps contradictory claims about the effectiveness of “narrowcasting,” or creating video content for small, specific audiences.

MAKING THE MOST OF YOUR HANDBOOK

Effective research writers often start by asking a question.

Posing questions for research: 50b

Posing questions for research: 50b

If your interest in a subject stems from your personal experience, you will want to ask what it is about your experience that would interest your audience and why. For example, if you have volunteered at a homeless shelter, you might have spent some time talking to homeless children and learning about their needs. Perhaps you can use your experience to broaden your readers’ understanding of the issues, to persuade an organization to fund an after-school program for homeless children, or to propose changes in legislation.

Whether or not you choose your own subject, it’s important to be aware of the expectations of each writing situation. The chart "Understanding an assignment" at the bottom of the page suggests ways to interpret assignments.

Purpose

Your purpose, or reason for writing, will often be dictated by your writing situation. Perhaps you have been asked to draft a proposal requesting funding for a student organization, to report the results of a psychology experiment, or to write about the controversy surrounding genetically modified (GM) foods for the school newspaper. Even though your overall purpose may be fairly obvious in such situations, a closer look at the assignment can help you make some necessary decisions. How detailed should the proposal be? How technical does your psychology professor expect your report to be? Do you want to inform students about the GM food controversy or to change their attitudes toward it?

In many writing situations, part of your challenge will be discovering a purpose. Asking yourself why readers should care about what you are saying can help you decide what your purpose might be. Perhaps your subject is magnet schools—schools that draw students from different neighborhoods because of features such as advanced science classes or a concentration on the arts. If you have discussed magnet schools in class, a description of how these schools work probably will not interest you or your readers. But maybe you have discovered that your county’s magnet schools are not promoting diversity as had been planned, and you want to call your readers to action.

Although no precise guidelines will lead you to a purpose, you can begin by asking, “Why am I writing?” and “What is my goal?” Identify which one or more of the following aims you hope to accomplish.

PURPOSES FOR WRITING

| to inform | to evaluate |

| to persuade | to recommend |

| to entertain | to request |

| to call readers to action | to propose |

| to change attitudes | to provoke thought |

| to analyze | to express feelings |

| to argue | to summarize |

Writers often misjudge their own purposes, summarizing when they should be analyzing, or expressing feelings about problems instead of proposing solutions. Before beginning any writing task, pause to ask, “Why am I communicating with my readers?” This question will lead you to another important question: “Just who are my readers?”

Audience

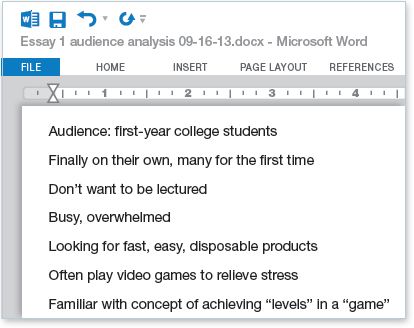

Audience analysis, a process in which you identify your readers and their expectations, can often lead you to an effective strategy for reaching your readers. A writer whose purpose was to persuade first-year college students to recycle began by making some observations about her audience:

Her analysis led the writer to appeal to her readers’ competitive nature and gaming experience—she invited college students to think about recycling as achieving different levels in a video game. Her audience analysis also warned her against adopting a preachy tone that her readers might find offensive. Instead of lecturing, she decided to draw examples from her own experience with the “levels” of being green—recycling paper and plastic, carrying a refillable water bottle, biking to campus, buying used clothing, taking notes on a laptop, and so on. The result was an essay that reached its readers instead of alienating them.

In some writing situations, the audience will not be defined for you. But the choices you make as you write will tell readers who you think they are (novices or experts, for example) and will show respect for your readers’ perspectives.

For help with audience analysis when composing e-mail messages, see the chart "Considering audience when writing e-mail messages" at the bottom of the page.

Academic audiences In college writing, considerations of audience can be more complex than they seem at first. Your instructors will read your essay, of course, but most instructors play multiple roles while reading. Their first and most obvious roles are as coach and evaluator; but they are also intelligent and objective readers, the kind of people who might reasonably be informed, entertained, or called to action by what you have to say and who want to learn from your insights and ideas.

Some instructors specify an audience, such as readers of a local newspaper, a hypothetical supervisor, or peers in a particular field. Other instructors expect you to imagine an audience appropriate to your purpose, subject, and genre. Still others prefer that you write for a general audience of educated readers—nonspecialists who can be expected to read with a critical eye.

Business audiences Writers in the business world often find themselves writing for multiple audiences. A letter to a client, for instance, might be distributed to sales representatives as well. Readers of a report might include people with and without technical expertise, or readers who want details and those who prefer a quick overview.

To satisfy the demands of multiple audiences, business writers have developed a variety of strategies: attaching cover letters to detailed reports, adding boldface headings, placing summaries in the margin, and using abstracts or executive summaries to highlight important points.

Public audiences Writers in communities often write to a specific audience—a legislative representative, readers of a local newspaper, fellow members of a social group. With public writing, it is more likely that you are familiar with the views your readers hold and the assumptions they make, so you may be better able to judge how to engage those readers. If you are writing to a group of other parents to share ideas for lowering school bus transportation costs, for instance, you may have a good sense of whether to lead with a logical analysis of other school-related fees or with a fiery criticism of key decision makers.

Genre

When writing for a college course, pay close attention to the genre, or type of writing, assigned. Each genre is a category of writing meant for a specific purpose and audience, with its own set of agreed-upon expectations and conventions for style, structure, and document design. Sometimes an assignment specifies the genre—an essay in a writing class, a lab report or research proposal in a biology class, a policy memo in a criminal justice class, or an executive summary in a business class. Sometimes the genre is yours to choose, and you need to decide if a particular genre—a poster presentation, an audio essay, a Web page, or a podcast, for example—will help you communicate your purpose and reach readers.

It is helpful to think of genre as an opportunity to enter a discipline and join a group of thinkers and writers who share interests, ideas, and ways of communicating with one another. For instance, if you are asked to write a lab report for a biology class or a case study for an education class, you have the opportunity to practice the methods used by scholars in these fields and to communicate with them. For the lab report, your purpose might be to present the results of an experiment; your evidence would be the data you collected while conducting your experiment, and you would use scientific terms expected by your audience. For the case study, your purpose might be to analyze student-teacher interactions in a single classroom; your evidence might be data collected from interviews and observations. (For a discussion of genres in various disciplines, see 65.)

To understand the expectations of different genres—and the opportunities present in different genres—you can begin by asking some of the following questions.

understanding genre

If the genre has been assigned, the following questions will help you focus on its expectations.

- Do you have access to samples of writing in the genre that has been assigned?

- Who is the audience? What interests, ideas, and beliefs do typical readers of the genre share?

- What type of evidence is usually required in the genre?

- What specialized vocabulary do readers expect in the genre?

- What citation style do readers expect?

- Does the genre require a specific format or organization?

If you are free to choose the genre, the following questions will help you focus on its expectations.

- What is your purpose for writing: To argue a position? To instruct? To present a process? To inspire? To propose?

- Who is your audience? What do you know about your readers or viewers?

- What method of presenting information would appeal to your audience: Reasoned paragraphs? Diagrams and pictures? Video? Slides?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of the genre you have chosen, given your purpose, audience, and deadline?

Sources of information

Where will your evidence—facts, details, and examples—come from? What kind of reading, observation, or research is necessary to meet the expectations of your assignment?

Reading Reading is an important way to deepen your understanding of a topic and expand your perspective. It will be your primary source of information for many college assignments. For example, if you are assigned to write a literature review for a psychology or biology class, you will need to read and evaluate the research that has been published about a particular topic. Or if you are assigned to write a case study for a nursing class, you will read and analyze detailed information about a client’s health issues.

Read with an open mind to learn from the insights and research of others. Take notes on your thoughts, impressions, and questions. Your notes can be a way to enter a conversation with the authors of the texts you read. (See 4.) And always keep careful records of any sources you read and consult.

Observation Observation is an excellent means of collecting information about a wide range of subjects, such as gender relationships on a popular television program, the clichéd language of sports announcers, or a current exhibit at the local art museum. For such subjects, do not rely on your memory alone; your information will be fresher and more detailed if you actively collect it, with a notebook, laptop, or voice recorder.

Interviews and questionnaires Interviews and questionnaires can supply detailed and interesting information on many subjects. A nursing student interested in the care of terminally ill patients might interview hospice nurses; a criminal justice major might speak with a local judge about alternative sentencing for first offenders; a future teacher might conduct a survey on the use of whiteboard technology in local elementary schools.

It is a good idea to record interviews to preserve any vivid quotations that you might want to weave into your essay. Circulating questionnaires by e-mail or on a Web site will facilitate responses. Keep questions simple, and specify a deadline to ensure that you get a reasonable number of replies. (See also 50e.)

Length and document design

Writers seldom have complete control over length requirements. Journalists usually write within strict word limits set by their editors, businesspeople routinely aim for conciseness, and most college assignments specify an approximate length.

Your writing situation may also require a certain document design. Specific formats are used in business for letters, memos, and reports. In the academic world, you may need to learn precise disciplinary and genre conventions for lab reports, critiques, research papers, and so on. For most undergraduate essays, a standard format is acceptable. (See the appendix.)

In some writing situations, you will be free to create your own design, complete with headings, displayed lists, and perhaps visuals such as charts and graphs.

Reviewers and deadlines

MAKING THE MOST OF YOUR HANDBOOK

Peer review can benefit writers at any stage of the writing process.

Guidelines for peer reviewers: page 58

Guidelines for peer reviewers: page 58

In college classes, the use of reviewers is common. Some instructors play the role of reviewer for you; others may suggest that you visit your college’s writing center. Still others schedule peer review sessions in class or online. Such sessions give you a chance to hear what other students think about your draft in progress. (See 2a.)

Deadlines are a key element of any writing situation. They help you plan your time and map out what you can accomplish in that time. For complex writing projects, such as research papers, you’ll need to plan your time carefully. By working backward from the final deadline, you can create a schedule of target dates for completing parts of the process. (See 50a for an example.)

Academic English

What counts as good writing varies from culture to culture and even among groups within cultures. In some situations, you will need to become familiar with the writing styles—such as direct or indirect, personal or impersonal, plain or embellished—that are valued by the culture or discipline for which you are writing.

Checklist for assessing the writing situation

Subject

- Has the subject (or a range of possible subjects) been assigned to you, or are you free to choose your own?

- What interests you about your subject? What questions would you like to explore?

- Why is your subject worth writing about? How might readers benefit?

- Do you need to narrow your subject (because of length restrictions, for instance)?

Purpose and audience

- Why are you writing: To inform readers? To persuade them? To call them to action? To offer an interpretation of a text?

- Who are your readers? How well informed are they about the subject? What do you want them to learn?

- How interested and attentive are your readers likely to be? Will they resist any of your ideas? What possible objections will you need to anticipate and counter?

- What is your relationship to your readers: Student to instructor? Citizen to citizen? Expert to novice? Employee to supervisor?

Genre

- What genre (type of writing) does your assignment require: A report? A proposal? An analysis of data? An essay?

- If the genre is not assigned, what genre is appropriate for your subject, purpose, and audience?

- What are the expectations and conventions of your assigned genre? For instance, what type of evidence is typically used in the genre?

- Does the genre require a specific design format or method of organization?

- Does the genre require or benefit from visuals, such as photos, drawings, or graphs?

Sources of information

- Where will your information come from: Reading? Research? Direct observation? Interviews? Questionnaires?

- What type of evidence suits your subject, purpose, audience, and genre?

- What documentation style is required: MLA? APA? Chicago?

Length and document design

- Do you have any length specifications? If not, what length seems appropriate, given your subject, purpose, audience, and genre?

- Is a particular document format required? If so, do you have guidelines to follow or examples to consult?

- How might visuals—charts, graphs, tables—help you convey information and support your purpose?

Reviewers and deadlines

- Who will be reviewing your draft: Your instructor? A writing center tutor? One or more classmates?

- What are your deadlines? How much time will you need to allow for the various stages of writing, including proofreading and printing or posting the final draft?

- Will you be sharing a draft electronically or in hard copy? If electronically, will your readers be able to handle your file’s size and format?

Understanding an assignment

Determining the purpose of an assignment

The wording of an assignment may suggest its purpose. You might be expected to do one or more of the following in a college writing assignment:

- summarize information from textbooks, lectures, or research (See 4c.)

- analyze ideas and concepts (See 4d.)

- take a position on a topic and defend it with evidence (See 6.)

- synthesize (combine ideas from) several sources and create an original argument (See 55c and 60.)

Understanding how to answer an assignment’s question

Many assignments will ask you to answer a how or why question. You cannot answer such questions using only facts; instead, you will need to take a position. For example, the question “What are the survival rates for leukemia patients?” can be answered with facts. The question “Why are the survival rates for leukemia patients in one state lower than those in a neighboring state?” must be answered with both facts and interpretation. If a list of questions appears in the assignment, be careful—instructors rarely expect you to answer all the questions in order. Look instead for topics or themes that will help you ask your own questions.

Recognizing implied questions

When you are asked to discuss, analyze, agree or disagree with, or consider a topic, your instructor will often expect you to answer a how or why question.

| Discuss the effects of the No Child Left Behind Act on special education programs. | = | How has the No Child Left Behind Act affected special education programs? |

| Consider the recent rise of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder diagnoses. | = | Why are diagnoses of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder rising? |

Considering audience when writing e-mail messages

In academic, business, and public contexts, you will want to show readers that you value their time. Here are some strategies for writing effective e-mails:

- Use a concise, meaningful subject line to help readers sort messages and set priorities.

- Put the most important part of your message at the beginning so that your reader sees it without scrolling.

- Write concisely; keep paragraphs short.

- For long, detailed messages, provide a summary at the beginning.

- Avoid writing in all capital letters or all lowercase letters.

- Proofread for typos and obvious errors that are likely to slow down readers.

You will also want to follow conventions of etiquette and avoid violating standards of academic integrity. Here are some strategies for writing responsible e-mails:

- E-mail messages can easily be forwarded to others and reproduced. Do not write anything that you would not want attributed to you.

- Do not forward another person’s message without asking his or her permission.

- If you write an e-mail message that includes someone else’s words—opinions, statistics, song lyrics, and so forth—let your reader know the source for that material and where any borrowed material begins and ends.

- Choose your words carefully because e-mail messages can easily be misread. Without your voice, facial gestures, or body language, a message can be misunderstood.

- Pay careful attention to tone; avoid writing anything that you wouldn’t be comfortable saying directly to a reader.