1b. Exploring your subject

Experiment with one or more techniques for exploring your subject and discovering your purpose:

- talking and listening

- reading and annotating texts

- asking questions

- brainstorming (listing ideas)

- clustering

- freewriting

- keeping a journal

- blogging

Whatever technique you turn to, the goal is the same: to generate ideas that will lead you to a question, a problem, or a topic that you want to explore further.

Talking and listening

Because writing is a process of figuring out what you think about a subject, it is useful to try out your ideas on other people. Conversation can deepen and refine your ideas before you begin to write them down. By talking and listening to others, you can also discover what they find interesting, what they are curious about, and where they disagree with you. If you are writing an argument, you can try it out on listeners with other points of view.

Many writers begin a project by brainstorming ideas in a group, debating with friends, or chatting with an instructor. Others prefer to record themselves by talking through their thoughts. Some writers exchange ideas by sending e-mail or texts or by posting to blogs. You may be encouraged to share ideas with your classmates and instructor in an online workshop where you can begin to explore your thoughts before starting a draft.

Reading and annotating texts

Reading is an important way to deepen your understanding of a topic, learn from the insights and research of others, and expand your perspective. Books, articles, reports, and visuals such as photographs, cartoons, videos, and other Web content can be important sources to explore as you generate ideas. Annotating a text, written or visual, encourages you to read actively—to highlight key concepts, to note contradictions in an argument, or to raise questions for further research and investigation. (See 4a for an annotated article and 5a for an annotated advertisement.)

Asking questions

When gathering material for a story, journalists routinely ask themselves Who? What? When? Where? Why? and How? In addition to helping journalists get started, these questions ensure that they will not overlook an important fact.

Whenever you are writing about ideas, events, or people, whether current or historical, asking questions is one way to get started. One student, whose topic was the negative reaction in 1915 to D. W. Griffith’s silent film The Birth of a Nation, began exploring her topic with this set of questions:

- Who objected to the film?

- What were the objections?

- When were protests first voiced?

- Where were protests most strongly expressed?

- Why did protesters object to the film?

- How did protesters make their views known?

MAKING THE MOST OF YOUR HANDBOOK

Effective college writers begin by asking questions.

Asking questions in academic disciplines: 64b

Asking questions in academic disciplines: 64b

As often happens, the answers to these questions led to another question the writer wanted to explore. After she discovered that protesters objected to the film’s racist portrayal of African Americans, she wondered whether their protests had changed attitudes. This question prompted an interesting topic for a paper: Did the film’s stereotypes lead to positive, if unintended, consequences?

In academic writing, scholars often generate ideas by posing questions related to a specific discipline. If you are writing in a particular discipline, try to find out which questions its scholars typically explore. Look for clues in assigned readings, assignments, and class discussions to understand how a discipline’s questions help you understand its concerns. (See 64.)

Brainstorming

Brainstorming, or listing ideas, is a good way to figure out what you know and what questions you have. Here is a list one student writer jotted down for an essay about community service requirements for college students:

Volunteered in high school.

Teaching adults to read motivated me to study education.

“The best way to find yourself is to lose yourself in the service of others.”—Gandhi

Volunteering helps students find interests and career paths.

Is required volunteering a contradiction?

Many students need to work to pay college tuition.

Enough time to study, work, and volunteer?

Can’t students volunteer for their own reasons?

What schools have community service requirements?

What do students say about community service requirements?

The ideas and questions appear here in the order in which they first occurred to the writer. Later she rearranged them, grouped them under general categories, deleted some, and added others. These initial thoughts led the writer to questions that helped her narrow her topic. In other words, she treated her early list as a source of ideas and a springboard to new ideas, not as an outline.

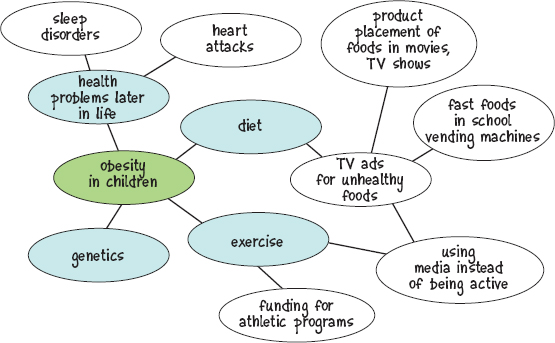

Clustering

Clustering (sometimes called mapping) emphasizes relationships among ideas. To cluster ideas, write your subject in the center of a sheet of paper, draw a circle around it, and surround the circle with related ideas connected to it with lines. Look for categories and connections among your ideas. The writer of the diagram below was exploring ideas for an essay on obesity in children.

Freewriting

In its purest form, freewriting is simply nonstop writing. You set aside ten minutes or so and write whatever comes to mind, without pausing to think about word choice, spelling, or even meaning. If you get stuck, you can write about being stuck, but you should keep your fingers moving. Freewriting lets you ask questions without feeling that you have to answer them. Sometimes a question that comes to mind at this stage will point you in an unexpected direction.

To explore ideas on a particular topic, consider using a technique known as focused freewriting. Again, you write quickly and freely, but this time you focus on a specific subject and pay attention to the connections among your ideas.

Keeping a journal

A journal is a collection of informal, exploratory, sometimes experimental writing. In a journal, often meant for your eyes only, you can take risks. You might freewrite, pose questions, comment on an interesting idea from one of your classes, or keep a list of questions that occur to you while reading. You might imagine a conversation between yourself and your readers or stage a debate to understand opposing positions. A journal can also serve as a sourcebook of ideas to draw on in future essays.

Blogging

Although a blog is a type of journal, it is a public writing space rather than a private one. In a blog, you might express opinions, make observations, recap events, play with language, or interpret an image. You can explore an idea for a paper by blogging about it in different ways or from different angles. One post might be your frustrated comments about the lack of parking for commuter students at your school. Maybe the next post shares a compelling statistic about the competition for parking spaces at campuses nationwide. Since most blogs have a commenting feature, you can create a conversation by inviting readers to give you feedback—ask questions, make counterarguments, or suggest other sources on a topic.