4a. Reading actively

Reading, like writing, is an active process that happens in steps. Most texts, such as the ones assigned in college, don’t yield their meaning with one quick reading. Rather, they require you to read and reread to grasp the gist, the main point, and to comprehend a text’s many layers of meaning.

When you read actively, you pay attention to details you would miss if you just skimmed a text and let its words slip past you. First, you read to understand the main ideas. Then you pay attention to your own reactions by making note of what interests, surprises, or puzzles you. Active readers preview a text, annotate it, and then converse with it. (See the charts at the bottom of the page.)

Previewing a text

Previewing—looking quickly through a text before you read—helps you understand its basic features and structure. A text’s title, for example, may reveal an author’s purpose; a text’s format or design may reveal what kind of text it is—a book, a report, a policy memo, and so on. As you preview, you can browse for illustrations, scan headings, and gain a sense of the text’s subsections. The more you know about a text before you read it, the easier it will be to dig deeper into it.

Annotating a text

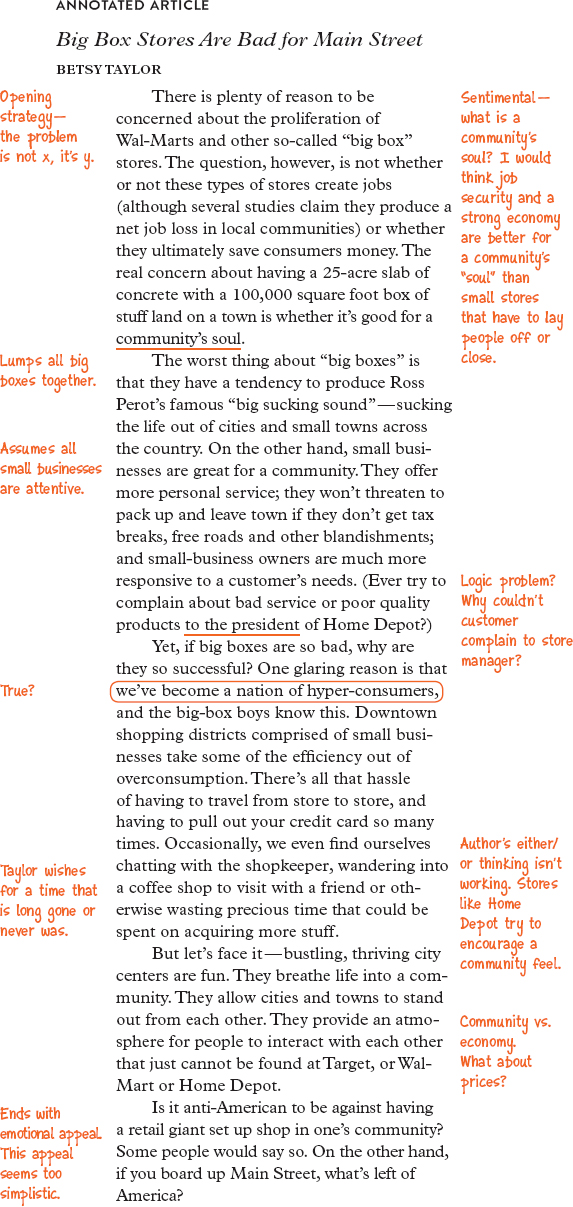

Annotating helps you capture and record your responses to a text. As you annotate, you take notes—you jot down questions and reactions in the margins of the text or on electronic or paper sticky notes. You might circle or underline the author’s main points or key ideas. Or you might develop your own system of annotating by placing question marks, asterisks, or stars by the text’s thesis or major pieces of evidence. Annotating a text will help you make sense of it and answer the basic question “What is this text about?”

As you annotate and think about a text, you are starting to write about it. Responding with notes helps you frame what you want to say about the author’s ideas or questions you want to address in response to the text. On a second or third reading, you may notice contradictions—statements the author makes that, put side-by-side, just don’t seem to make sense—or surprising insights that may lead to further investigation. Each rereading will raise new questions and lead to a better understanding of the text.

The following example shows how one student, Emilia Sanchez, annotated an article from CQ Researcher, a newsletter about social and political issues.

Conversing with a text

Conversing with a text—or talking back to a text and its author—helps you move beyond your initial notes to draw conclusions about what you’ve read. Perhaps you ask additional questions, point out something that doesn’t make sense, or use the author’s points to spark related ideas. As you talk back to a text, you dig a little deeper into it. You look more closely at how the author works through a topic, and you judge the author’s evidence and conclusions. Conversing takes your notes to the next level—and is especially helpful when you have to write about a text. For example, student writer Emilia Sanchez noticed on a first reading that her assigned text closed with an emotional appeal. On a second reading, she questioned whether that emotional appeal worked or whether it was really too simplistic.

Many writers use a double-entry notebook to converse with a text and its author. To create one, draw a line down the center of a notebook page. On the left side, record what the author says; include quotations, sentences, and key terms from the text. On the right side, record your observations and questions. This is your opportunity to converse with an author and to generate ideas. With each rereading of a text, you can return to your notebook to add new insights or questions.

A double-entry notebook allows you to begin to see the difference between what a text says and what it means and to visualize the conversation between you and the author as it develops.

Here is an excerpt from student writer Emilia Sanchez’s double-entry notebook.

| Ideas from the text | My responses |

| “The question, however, is not whether or not these types of stores create jobs (although several studies claim they produce a net job loss in local communities) or whether they ultimately save consumers money” (1011). | Why are big-box stores bad if they create jobs or save people money? Taylor dismisses these possibilities without acknowledging their importance. My family needs to save money and needs jobs more than “chatting with the shopkeeper” (1011). |

| “The real concern . . . is whether [big-box stores are] good for a community’s soul” (1011). “[S]mall businesses are great for a community” (1011). |

Taylor is missing something here. Are all big-box stores bad? Are all small businesses great? Would getting rid of big-box stores save the “soul” of America? Is Main Street the “soul” of America? Taylor sounds overly sentimental. She assumes that people spend more money because they shop at big-box stores. And she assumes that small businesses are always better for consumers. |

note: To create a digital double-entry notebook, you can use a table or text boxes in a word processing program.

using sources responsibly: Remember to put quotation marks around words you have copied and to keep an accurate record of page numbers for quotations as well as for ideas you have noted on the left side.

Asking the “So what?” question

As you read and annotate a text, make sure you understand its thesis, or central idea. Ask yourself: “What is the author’s thesis?” Then put the author’s thesis to the “So what?” test: “Why does this thesis matter? Why does it need to be argued?” Perhaps you’ll conclude that the thesis is too obvious and doesn’t matter at all—or that it matters so much that you feel the author stopped short and overlooked key details. You’ll be in a stronger position to analyze a text after putting its thesis to the “So what?” test.

- Academic reading and writing > As you write: Reading actively

Guidelines for active reading

Preview a written text.

- Who is the author? What are the author’s credentials?

- What is the author’s purpose: To inform? To persuade? To call to action?

- Who is the expected audience?

- When was the text written? Where was it published?

- What kind of text is it: A book? A report? A scholarly article? A policy memo?

- Does the text have illustrations, charts, or photos? Is it divided into subsections?

Annotate a written text.

- What surprises, puzzles, or intrigues you about the text?

- What question does the text attempt to answer? Or what problem does it attempt to solve?

- What is the author’s thesis, or central claim?

- What type of evidence does the author provide to support the thesis? How persuasive is this evidence?

Converse with a written text.

- What are the strengths and limitations of the text?

- Has the author drawn conclusions that you want to question? Do you have a different interpretation of the evidence?

- Does the text raise questions that it does not answer?

- Does the author consider opposing points of view? Does the author seem to treat sources fairly?

Ask the “So what?” question.

- Why does the author’s thesis need to be argued, explained, or explored? What’s at stake?

- What has the author overlooked or failed to consider in presenting this thesis? What’s missing?

- Could a reasonable person draw different conclusions about the issue?

- To put an author’s thesis to the “So what?” test, use phrases like the following: The author overlooks this important point: . . . and The author’s argument is convincing because. . . .

Reading online

For many college assignments, you will be asked to read online sources. Research has shown that readers tend to skim and browse online texts rather than read them carefully. On the Web, it is easy to become distracted. And when you skim a text, you are less likely to remember what you have read and less inclined to reread to grasp layers of meaning.

The following strategies will help you read critically online.

Read slowly. Focus and concentration are the goals of all reading, but online readers need to work against the tendency to skim. Instead of sweeping your eyes across the page, consciously slow down the pace of your reading to focus on each sentence.

Avoid multitasking. Close other applications, especially e-mail and social media. If you follow a link for background or the definition of a term, return to the text immediately.

Annotate electronically. You can take notes and record questions on electronic texts. In a print-formatted electronic document (such as a PDF version of an article), you can use the highlighting features in your PDF reader. You might also use electronic sticky notes or the comment feature in your word processing program.

Print the text. You may want to save a text to a hard drive, USB drive, or network and then print it (making sure to record information about the source for proper citation later). Once you print it, you can easily annotate it.