5a. Reading actively

Any image or multimodal text can be read—that is, carefully approached and examined to understand what it says and how it communicates its purpose and reaches its audience. Like written texts, images and multimodal texts don’t speak for themselves; they don’t reveal their meaning with a quick glance or a casual scan. Rather, you need to read and reread, questioning and conversing with them with an open, critical mind.

MAKING THE MOST OF YOUR HANDBOOK

Integrating visuals (images and some multimodal texts) can strengthen your writing.

Adding visuals to your draft: page 43

Adding visuals to your draft: page 43

Choosing visuals to suit your purpose: pages 44-45

Choosing visuals to suit your purpose: pages 44-45

When you read a multimodal text in particular, you are often reading more than words; you might also be reading a text’s design and composition—and perhaps even its pace and volume. Your work involves understanding the modes—words, images, and sound—separately and then analyzing how the modes work together—the interaction among words, images, and sound. As you read a multimodal text, pay attention to the details that make up the entire composition.

When you read images or multimodal texts, it’s helpful to preview, annotate, and converse with the text—just as with print texts.

Previewing an image or a multimodal text

Previewing starts by looking at the basic details of an image or a multimodal text and paying attention to first impressions. You begin to ask questions about the text’s subject matter and design, its context and composer or creator, and its purpose and intended audience. The more you can gather from a first look, the easier it will be to dig deeper into the meaning of a text. The following questions will help you as you preview.

first impressions. What strikes you right away? What do you notice that surprises, intrigues, or puzzles you about the text? What is the overall effect of the text?

genre. What kind of text is it: Advertisement? Photograph? Video? Podcast?

purpose. What is the text’s purpose: To persuade? To inform? To entertain? If the text is an advertisement, what product or idea is it selling?

audience. Who is the target audience? What assumptions are made about the audience?

context. Where was the text originally published or viewed?

design. What seems most prominent in the text’s design?

Annotating an image or a multimodal text

Annotating a text—jotting down observations and questions—helps you read actively to answer the basic question “What is this text about?” In annotating, you pay close attention to details—what they imply and how they relate to one another and to the whole image or multimodal text.

When you annotate a text, you are starting to write about it. Often, you are beginning to figure out what you want to say about the composer’s choices. You’ll often find yourself annotating, rereading, and moving back and forth between reading and writing to fully understand and analyze an image or a multimodal text. A second or third reading will raise new questions and reveal details or contradictions that you didn’t notice in an earlier reading. The following techniques will help you annotate an image or a multimodal text.

- For a still image, download, copy and paste, or scan the image into a word processing document or a PowerPoint slide so that you can use the space of the page or slide to take notes. Most word processing applications will allow you to copy and paste images and text from a Web page into a word processing page.

- For a video or sound file, create a separate note-taking document in a word processing file or in a traditional notebook. Use the time stamp, if there is one, as you take notes: 04:21 The music stops abruptly, and a single word, “Care,” appears on-screen.

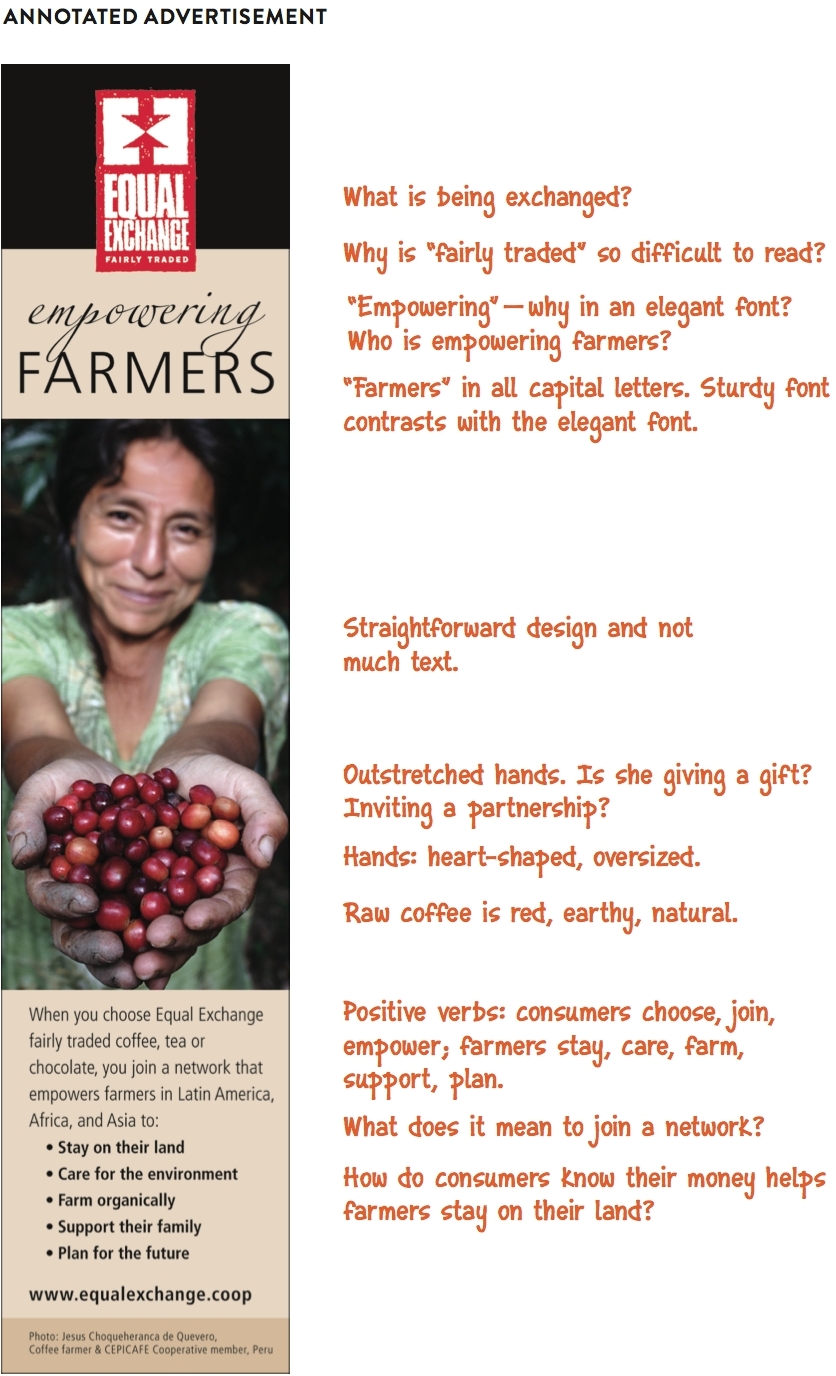

The following example shows how one student, Ren Yoshida, annotated an advertisement.

Conversing with an image or a multimodal text

Conversing with a text—or talking back to a text and its author—helps you move beyond your early notes to form judgments about what you’ve read. At this stage, you dig a little deeper into the text, perhaps posing more questions, pointing out something that is puzzling or provocative and why, or explaining a disagreement you have with the text. Conversing takes your notes to the next level—and is especially helpful when you have to write about a text. In his annotations to the Equal Exchange ad, notice that Ren Yoshida asks why two words, empowering and farmers, are in different fonts. And he further questions the purpose and meaning of the difference.

Many writers use a double-entry notebook to converse with a text and generate ideas for writing (see 4a for guidelines on creating a double-entry notebook and sample entries). A double-entry notebook allows you to separate what a text says and does from what a text means. As you record details and features of an image or a multimodal text on the left side of the notebook page and your own responses on the right side, you can visualize the conversation as it develops.