52e. Assessing Web sources with care

Sources found on the Web can provide valuable information, but verifying their credibility may take time. Before using a Web source in your paper, make sure you know who created the material and for what purpose. Sites with reliable information can stand up to careful scrutiny. For a checklist on evaluating Web sources, see the chart at the bottom of the page.

Student writer Ned Bishop came across unreliable Web sources while researching his topic, the Fort Pillow massacre. This topic is of great interest to Civil War buffs, who might not have scholarly backgrounds. One impressive-looking site turned out to have been created by a high school junior—an intelligent young man, no doubt, but not an authority on the subject.

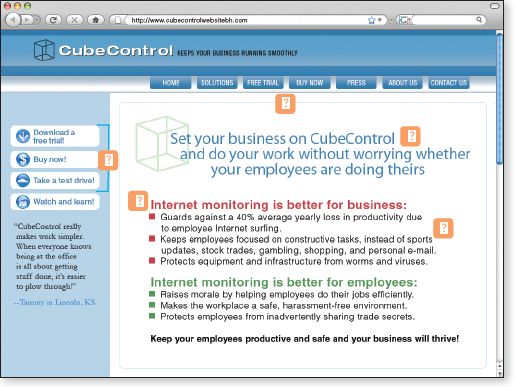

In researching Internet surveillance and workplace privacy, student writer Anna Orlov encountered sites that raised her suspicions. In particular, some sites were authored by surveillance software companies, which have an obvious interest in focusing on the benefits of such software to company management.

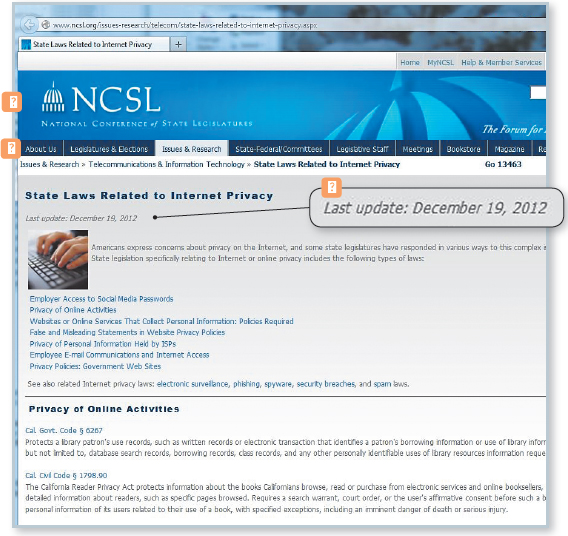

Knowing that the creator of a site is an amateur or could be biased is not sufficient reason, however, to reject the site’s information out of hand. For example, the surveillance software companies’ Web sites provided some insight into why company management would want to monitor employees, and the high school junior had intelligent things to say about the Fort Pillow massacre. Nevertheless, when you know something about the creator of a site and have a sense of a site’s purpose, you will be in a good position to evaluate the likely worth of its information. Consider, for example, the two sites pictured below. Anna Orlov decided that the first Web site would be more useful for her project than sites like the second.

evaluating a web site: checking reliability

evaluating a web site: checking purpose

Assessing multimodal sources with your research question in mind

You may find that, for your topic, the best sources are videos such as public service ads or interviews delivered as podcasts or blog posts that include opinion, data, or graphics. Though these are generally not considered scholarly sources, such sources may be perfectly appropriate given your topic, your purpose, and your audience. When student writer Anna Orlov entered a debate about the rights of employers to monitor employees’ time on the Web, she used a CBS video that she found on YouTube. It added the perspective and the evidence she needed: employers discussing the uses of the social Web for corporate benefit.

- Researched writing > As you write: Developing an annotated bibliography

- Researched writing > Sample student writing

> Orlov, “Online Monitoring: A Threat to Employee Privacy in the Wired Workplace: An Annotated Bibliography” (annotated bibliography)

> Niemeyer, “Keynesian Policy: Implications for the Current U.S. Economic Crisis” (annotated bibliography)

- Researched writing > As you write: Evaluating sources you find on the Web

Evaluating sources you find on the Web

Authorship

- Does the Web site or document have an author? You may need to do some clicking and scrolling to find the author’s name. If you have landed directly on an internal page of a site, for example, you may need to navigate to the home page or find an “about this site” link to learn the name of the author.

- If there is an author, can you tell whether he or she is knowledgeable and credible? When the author’s qualifications aren’t listed on the site itself, look for links to the author’s home page, which may provide evidence of his or her interests and expertise.

Sponsorship

- Who, if anyone, sponsors the site? The sponsor of a site is often named and described on the home page.

- What does the URL tell you? The domain name extension often indicates the type of group hosting the site: commercial (.com), educational (.edu), nonprofit (.org), governmental (.gov), military (.mil), or network (.net). URLs may also indicate a country of origin: .uk (United Kingdom) or .jp (Japan), for instance.

Purpose and audience

- Why was the site created: To argue a position? To sell a product? To inform readers?

- Who is the site’s intended audience?

Currency

- How current is the site? Check for the date of publication or the latest update, often located at the bottom of the home page or at the beginning or end of an internal page.

- How current are the site’s links? If many of the links no longer work, the site may be too dated for your purposes.