5: Verbal Communication

As a poet, motivational speaker, and actor, Ed Mabrey spends his life carefully crafting his words. His hard work has paid off. Mabrey is a two-time winner of the Individual World Poetry Slam Championship (2007 and 2012).1 In this annual competition featuring dozens of the world’s best performance poets—each of whom is a champion in his or her home region—Mabrey and others get to show off their unique talents.

Mabrey’s recent victories have cemented his status as one of the finest performance poets ever: two-time Haiku slam champion, 2012 Poetry Slam Artist of the Year, and four-time National Poetry Slam Finalist.

Poetry slam is the competitive art of performance poetry. Unlike written poetry, which is designed to be read, performance poetry is created to be spoken in front of a live audience. At poetry slams, judges assess poets and award them points. Although slams vary in their rules, most require that the poems be brief and that poets perform without props, costumes, or musical instruments. Poets are judged solely on their choice of words and the emotion with which these words are communicated to the audience.

The poetry performed at slams varies widely in topic—everything from comedy to social commentary, inner reflection to outward expression of love. Champion Ed Mabrey’s poetry focuses on his view of world events, his close relationships, and even casual encounters. His poem “Pursuit of Happyness,” for example, is about a conversation with a homeless person at a Subway restaurant.

No longer limited to coffee shops or bookstores, poetry slams also exist online. Poetry Slam, Inc., which organizes national and international competitions, hosts a video slam contest, in which poets submit videotaped performances and have online audience members vote for the one they like best. A recent winner of the video slam was Kait Rokowski, who provided a blistering performance regarding gender roles and sexual assault (you can see Kait’s poem on YouTube).

But despite the diversity among poets, poetic content, and medium, the common theme that runs throughout all performance poetry is the importance of carefully choosing clear, honest, and understandable language packed with powerful meaning. Poets seeking to win slams can’t just craft language into small, elegant poems. They must verbally communicate their creations to audiences in a competent fashion. Although poetry slams are highly competitive—poets intensely vie with one another for points and tenths of points—they are ultimately about celebrating the communicative power of the spoken word. As poet Allan Wolf describes, “The points are not the point; the point is poetry.”

CHAPTER OUTLINE

You may not be a performance poet like Ed Mabrey or Kait Rokowski, facing audiences and judges who evaluate you through points. But you are judged just the same, every single day, based on the words you choose. If you competently communicate to others, you’re awarded “points” in the form of people liking you, being influenced by you, or judging you to have desirable skills—like being “an amazing speaker” or “a skilled conversationalist.” Regardless of your personal rhyme or reason, your words pack a potent punch in shaping others’ impressions of you. As a consequence, it’s important to understand the power of verbal communication and how to use it competently. In this chapter, you’ll learn:

- The four defining features of language

- Strategies for creating understandable messages and taking responsibility for your words

- How to use language that avoids gender bias and is mindful of cultural differences

- Ways to manage the challenging aspects of verbal communication

The Nature of Verbal Communication

LearningCurve can help you review! Go to bedfordstmartins.com/choicesconnections.

LearningCurve can help you review! Go to bedfordstmartins.com/choicesconnections.

Your days are filled with verbal communication. You talk with your professor during her office hours, then text your roommate to see if you can get a ride home. You e-mail group members about an upcoming project, then give a speech in front of your communication class. You chat with coworkers after your shift, then Skype with your partner stationed overseas. Through all of these exchanges, you employ verbal communication—the use of spoken or written language to interact with others. Because language is the basis of verbal communication, understanding the nature of language is key for improving your verbal communication skills. Language has four defining features: it is symbolic, it is rule governed, it conveys meaning, and it is intertwined with culture.

Language Is Symbolic

When Steve was in sixth grade, his friend Ed would play an annoying word game with people. Ed would point to a table and say, “What’s that?” The unwitting victim would answer, “It’s a table, duh!” Ed would say, “No, that’s just the word we use to represent it. What’s it really?” The person would pause, then respond, “Oh, I see. OK, it’s wood and metal and plastic.” “No,” Ed would laugh, “those are just words that we use to represent what it is. What is it really?” About this time the person would get fed up with Ed’s game and walk away.

Ed’s game illustrates the first defining feature of language: it is symbolic. When items are used to represent other things, they are considered symbols. In verbal communication, words are the primary symbols used to represent people, objects, events, and ideas (Foss, Foss, & Trapp, 1991). Thus, the word table refers to an object with a flat surface and legs to support it. You could just as well call it a “cotknee” or some other term. If you did, nothing about the actual object would change—just its name. As psychologist Erich Fromm noted, words only point to our experience of the world; they are not the experience. All languages are collections of symbols in the form of words people use to communicate.

Language Is Rule Governed

Two types of rules govern the use of language. The first type is constitutive rules, which define words’ meanings. Constitutive rules tell you what words “count as” what objects (Searle, 1965). For example, in the English language, dog represents a four-legged domesticated animal that is a common household pet. In Spanish, the word perro represents this same animal. Constitutive rules involving informal or metaphorical expressions can make things challenging when you’re trying to learn a new language. For example, someone new to English may get confused when a friend says, “My dogs are tired,” if the speaker really means, “My feet hurt.”

The second type comprises regulative rules, which control how you use language. Regulative rules guide everything from spelling to grammar to conversational structure. Examples in the English language include “Add an ‘s’ or an ‘es’ to a noun to create its plural form” and “When someone asks you a question, you should answer.”

Language Conveys Meaning

Language enables you to convey meaning to others in two ways. The first is the literal meaning of your words, as agreed on by members of your culture. These are known as denotative meanings. Such meanings are what you find in dictionaries; for example, family means “a group of individuals related through common ancestry, legal means, or other strong emotional or social bonds.” But the word family evokes different meanings for different people. Some may hear the word and immediately think, “Individuals I can count on for love and support.” Others may hear it and think, “People who are always judging me!” Such variations represent connotative meanings—the meanings you associate with words based on your life experiences. What does the word family mean to you?

Denotative and connotative meanings can create confusion if you don’t manage them carefully. For example, suppose your friend aces an exam that you flunked. You text her, “I hate u!” The denotative meaning suggests you feel hatred toward your friend. But the connotative meaning—your real message—is “I’m envious but proud of you.” If you and your friend have a history of communicating with each other in this way, your friend will probably read your message as you intend. But with a person you don’t know as well, an “I hate u!” text could backfire. To use verbal communication competently, choose your words carefully and clarify connotative meanings if there’s a chance someone could misunderstand your message.

CONNOTATIVE MEANINGS: THIS OR THAT? Depending on your personal experiences, the word gambling can have vastly different connotative meanings. When a friend says she is going gambling, do you think that sounds fun, boring, wasteful, or something else entirely?

Tim Pannell/Corbis and Ken Seet/Corbis

Language and Culture Are Intertwined

Members of a culture use language to communicate their thoughts, beliefs, attitudes, and values with one another, and thereby reinforce their collective sense of cultural identity (Whorf, 1952). Consequently, the language you speak (English, Spanish, Mandarin, Urdu), the words you choose (proper, slang, profane), and the grammar you use (formal, informal) all announce to others: “This is who I am! This is my cultural heritage!”

Each language reflects distinct sets of cultural beliefs and values. However, a large group of people within a particular culture who speak the same language may (over time) develop their own variations on that language, known as dialects (Gleason, 1989). Dialects may include unique phrases, words, and pronunciations (such as accents). Dialects reflect the shared history, experiences, and knowledge of people who live in a particular geographic region (the American Midwest or the Deep South), share a common socioeconomic status (urban working class or upper-middle-class suburban), or possess a common ethnic or religious ancestry (Irish English or Yiddish English) (Chen & Starosta, 1998).

People often judge those who use dialects similar to their own as ingroupers and are thus inclined to make positive judgments about them (Delia, 1972; Lev-Ari & Keysar, 2010). As Chapter 4 discusses, this is a cultural influence; ingroupers are people you perceive to be culturally similar to yourself. In a parallel fashion, people tend to judge those with dissimilar dialects as outgroupers (people who are culturally dissimilar to you) and make negative judgments about them. Keep this tendency in mind when you’re speaking with people who don’t share your dialect, and resist the temptation to make negative judgments about them. For additional ideas on managing ingroup or outgroup perceptions, see Chapter 4.

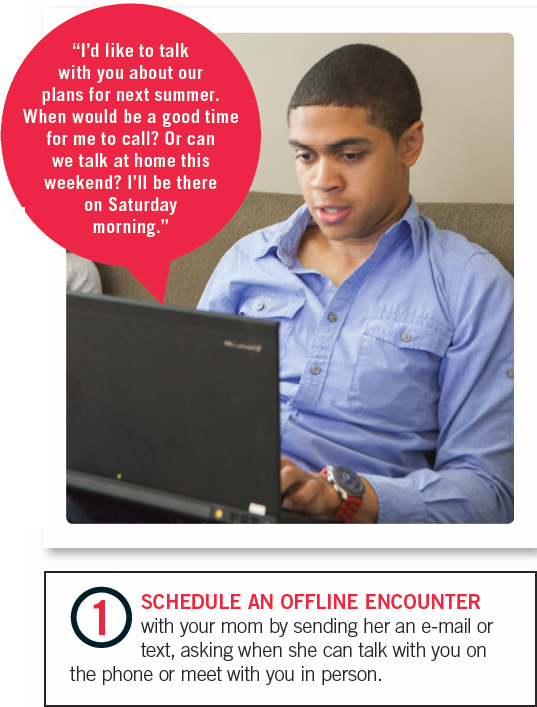

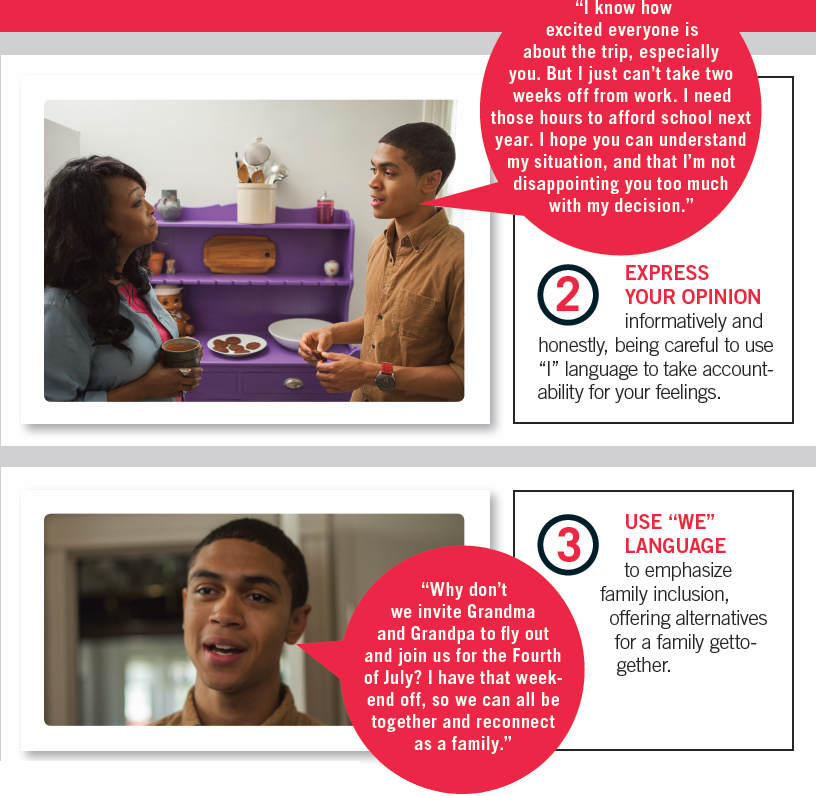

One way to improve your communication competence is by adapting your messages to others’ behaviors. Learn how to navigate a disagreement with a family member by going to LaunchPad at

One way to improve your communication competence is by adapting your messages to others’ behaviors. Learn how to navigate a disagreement with a family member by going to LaunchPad at

WHAT IF? But what if things don’t work out as shown? Test your ability to adapt your communication by watching the What if? videos and planning a response for each situation.

WHAT IF? But what if things don’t work out as shown? Test your ability to adapt your communication by watching the What if? videos and planning a response for each situation.

LearningCurve can help you review! Go to

LearningCurve can help you review! Go to  How to Communicate video scenarios

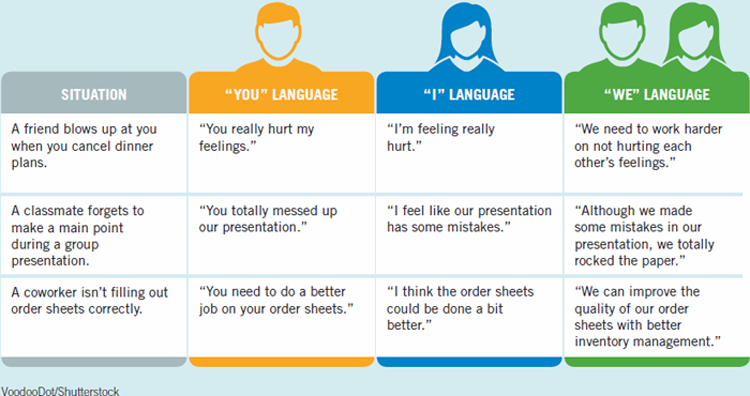

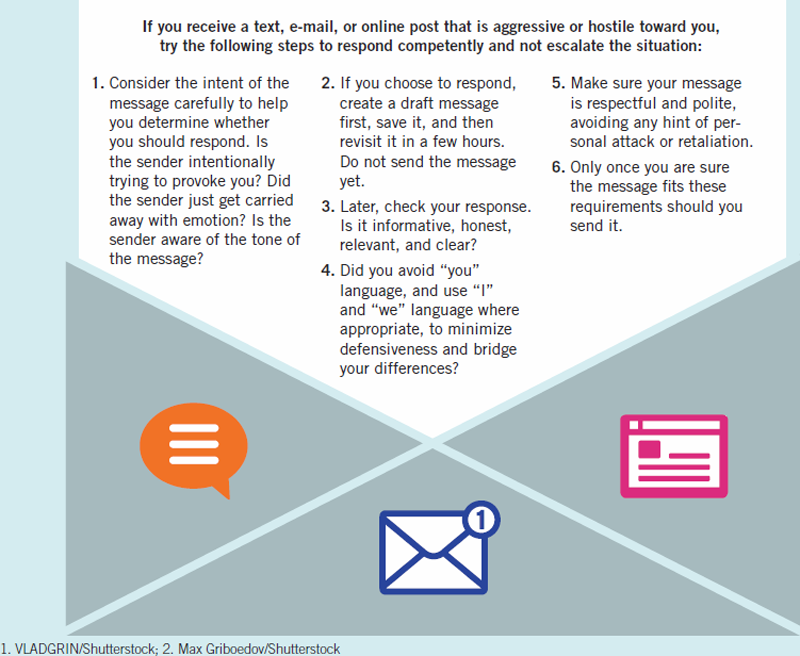

How to Communicate video scenarios “You” language, p. 119

“You” language, p. 119