Attributions and Perceptual Errors

Following the perception process, you often want explanations for why things are happening the way they are (“Why is Tom not talking during the meeting?”). These explanations are known as attributions. Two types of attributions are commonplace. One is that external factors or events—things outside of the person—caused the person’s behavior (“Tom just heard that his dad is sick, so he’s thinking about that instead of taking part in the meeting”). The other is that internal factors—personality, character, emotions—caused the person to act as he or she did (“Tom is a moody jerk, and that’s why he’s not contributing”).

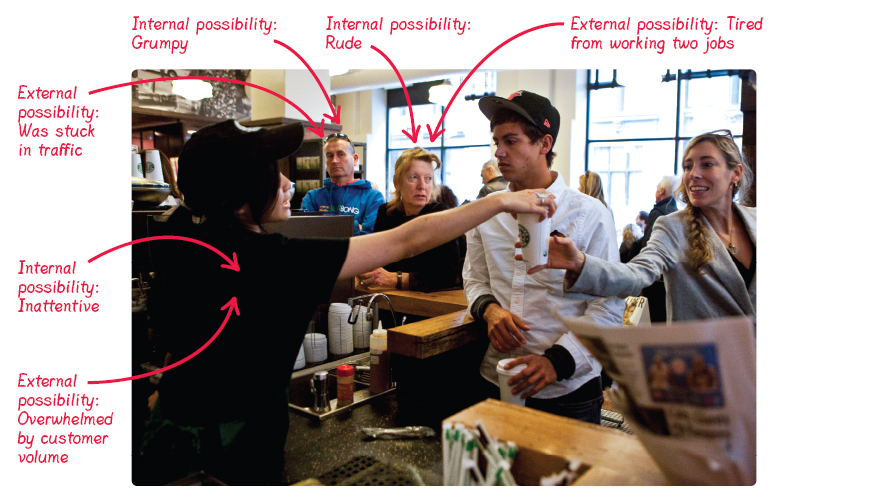

FUNDAMENTAL ATTRIBUTION ERROR

Given the number of people you communicate with each day, it’s not surprising that you occasionally form invalid attributions. One common mistake is the fundamental attribution error, the tendency to attribute others’ behaviors to internal rather than external forces (Heider, 1958). The fundamental attribution error is the most prevalent of all perceptual errors (Langdridge & Butt, 2004). When you communicate with others, they—not the surrounding factors that may be causing their behavior—dominate your perception. As a result, when you make judgments about why someone is acting a certain way, you overestimate the influence of the person and underestimate the influence of external factors (Heider, 1958; Langdridge & Butt, 2004).

A related error is the actor-observer effect, the tendency to make external attributions regarding your own behaviors (Fiske & Taylor, 1991). During encounters with others, you tend to focus on external factors—especially the people you’re interacting with. Therefore, you tend to identify these external factors as causing your behavior. This is particularly prevalent during unpleasant interactions. For example, if you’re giving a speech and the audience doesn’t pay attention, you might get angry and feel that such anger is a justifiable reaction to audience members’ rudeness rather than a lack of self-control on your part.

However, when your actions result in success, you tend to take credit for the success by making an internal attribution (“The audience paid attention because I’m a skilled speaker”). This tendency is known as the self-serving bias (Fiske & Taylor, 1991). By crediting yourself for your successes, you feel better about who you are and the skills you possess.

Your attributions directly influence how you communicate with others and the outcomes that result. For example, imagine that your partner forgets to pick up your dry cleaning on the way home from work. If you attribute your partner’s forgetfulness to work pressures and a hectic schedule (external causes), you’ll probably communicate in a supportive way (“I know how busy you are—I should’ve texted you a reminder”). But if you make internal attributions (“my partner is self-centered and inconsiderate”), you’ll likely communicate in a destructive way (“I’m sure you’d remember if it were your stuff that needed picking up!”).