Create Understandable Messages

In his exploration of language and meaning, philosopher Paul Grice noted that in order for people to have competent interactions, they tailor their messages so that others can understand them. To produce understandable messages, you can apply the cooperative principle: making your verbal communication as informative, honest, relevant, and clear as required for a particular situation (Grice, 1989).

Be Informative.Being informative means presenting all of the information that is appropriate and important to share. It also means avoiding providing information that isn’t appropriate or important. For example, suppose your sister is getting married and you are in the wedding party. When you make a toast at the reception following the ceremony, everyone will expect you to comment on how the couple met and how their love for each other is inspiring. To not say these things would be remiss. On the other hand, you won’t want to be too informative by sharing inappropriate details (such as stories about their sex life) or unimportant details (such as what was on the menu at the restaurant where they first met).

UNDERSTANDABLE MESSAGES

Be Honest.Honesty is the single most important characteristic of competent communication, because other people count on the fact that the information you share with them is truthful (Grice, 1989). Being honest means not sharing information you’re uncertain about and not presenting information as true when you know it’s false. For example, let’s say that during a meeting, someone asks you a question you’re unable to answer. Rather than fumbling through a potentially incorrect response, acknowledge that you don’t know the answer, and determine a way to get the required information. Dishonesty in verbal communication violates standards for ethical behavior and leads others to believe false things (Jacobs, Dawson, & Brashers, 1996).

Be Relevant.You are relevant when you present information that’s responsive to what others have said and applicable to the situation. As examples of responsiveness, when people ask you questions, you provide appropriate answers. When they make requests, you explicitly grant or reject those requests. Dodging questions or abruptly changing topics is uncooperative and may be seen as deceptive. In the wedding toast scenario, a relevant speech would cover the couple’s relationship. Going off on tangents regarding your own relationships would be irrelevant (“Seeing them together reminds me of my own love life; just last week I . . .”).

Be Clear.Using clear language means presenting information in a straightforward fashion rather than framing it in vague or ambiguous terms. This was one of the most impressive aspects of Gates Sr.’s commencement speech: he used clear, concise language that everyone easily understood: “People suffering in poverty . . . have mothers who love them.” (Check out Chapter 15 for suggestions on how to use clear language in your own speeches.)

At the same time, using clear language doesn’t mean being brutally frank or dumping offensive or harmful information on others. When you find yourself in situations in which you have to deliver bad news (“Your project report needs serious revision”), tailor your message in ways that consider others’ feelings (“I’m sorry for the inconvenience this may cause you”). Similarly, you’ll improve the likelihood of positive outcomes during conflicts by expressing your concerns clearly (“I’m really upset”) while avoiding language that attacks someone’s character or personality (“You’re such an idiot”) (Gottman & Silver, 1999).

Misunderstandings.Of course, just because you use informative, honest, relevant, and clear language doesn’t guarantee that others will understand you. When one person misperceives the meaning of another’s verbal communication, misunderstanding occurs.

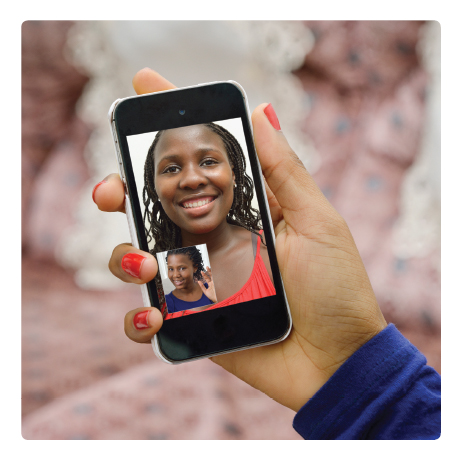

Misunderstanding occurs frequently online, owing to the lack of nonverbal cues that help clarify intended meaning. One study found that 27.2 percent of respondents agreed that e-mail is likely to result in miscommunication of intent, and 53.6 percent agreed that it is relatively easy to misinterpret an e-mail message (Rainey, 2000). The tendency to misunderstand communication online is so prevalent that scholars suggest the following practices: If a particular message must be absolutely error-free or if its content is controversial, don’t use e-mail or text messaging to communicate it. Whenever possible, conduct high-stakes encounters, such as important attempts at persuasion, face-to-face. Never use e-mails, posts, or texts for sensitive actions, such as professional reprimands or dismissals, or relationship breakups (Rainey, 2000). To learn how to create understandable messages and avoid misunderstandings during conflicts, see How to Communicate: Disagreement with Family on pages 120–121.