Family Relationships

Families today are incredibly diverse. Since 2010, only 20 percent of U.S. households consist of married couples with biological children; within Canada, it is only about 35 percent. Couples are increasingly living together rather than getting married, and rising divorce and remarriage rates have led to blended arrangements featuring stepparents and stepchildren. Adding to this complexity, individual families are constantly in flux, as children leave home, then move back in with parents while looking for work; as grand-parents join the household to help with day care or receive care themselves; and as spouses separate geographically to pursue job opportunities (Crosnoe & Cavanagh, 2010).

To embrace this diversity, we use a broad and inclusive definition of family. A family is a network of people who share their lives over long periods of time and are bound by marriage, blood, or commitment; who consider themselves a family; and who share a significant history and an anticipated future of functioning in a family relationship (Galvin, Brommel, & Bylund, 2004). This definition highlights three characteristics that distinguish families from other relationship types: shared identity, multiple roles, and emotional complexity.

Shared Identity.Families possess a strong sense of shared identity: “We’re the MacTavish clan, and we’ve always been adventurous” or “We Singhs have a long history of creative talent.” This sense of shared identity is created by three factors, the first of which is how the family communicates (Braithwaite et al., 2010). The stories you exchange and the way members of your family deal with conflict and talk with one another all contribute to a shared sense of what your family is like (Tovares, 2010). For instance, our friend Lorena’s great-grandparents emigrated from their farm in Sicily to the United States. To build a life in their adopted country, they learned English, worked in textile mills, and eventually bought their own home. But they also endured taunts and mistreatment from people who looked down on immigrants. Lorena remembers at-tending multigenerational family dinners at their home on Sundays, where everyone re-counted stories about how tough and resilient her “Nana and Nano” were to succeed in America—and how they passed on these same qualities to the next generations.

In addition to how a family communicates, genetic material can further foster a sense of shared identity (Crosnoe & Cavanagh, 2010). This can lead to shared physical traits—such as distinct hair colors, body types, and facial characteristics—as well as similar personalities, mental abilities, and ways of relating to others.

Finally, a common history can also help create a sense of shared identity (Galvin et al., 2004). Such histories can stretch back for generations and may feature family members from a broad array of cultures. In The Descendants, for instance, Matt King’s family is incredibly diverse but bonded by their heritage as native Hawaiian royalty. The history you share with your family is created jointly, as you go through time together. For better or worse, everything you say and do becomes a part of your family history.

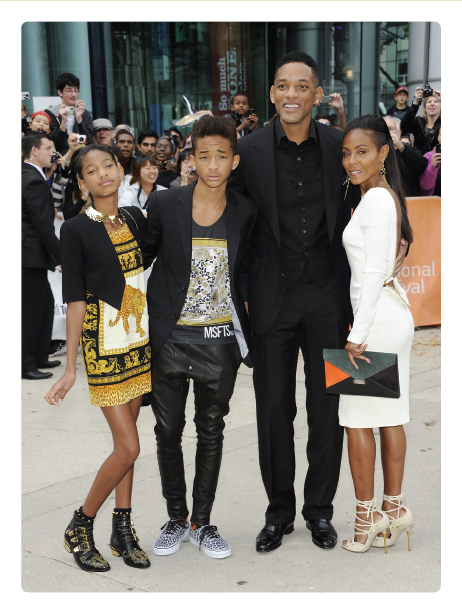

Multiple Roles.Family members constantly juggle multiple roles (Silverstein & Giarrusso, 2010). When you’re a lover, a friend, or a coworker, you’re just that: lover, friend, or coworker. Within your family, however, you’re not just a daughter or a son—you may also be a sibling, a spouse, and an aunt or an uncle. By the time you reach middle age, you may simultaneously be parent, spouse, grandparent, daughter or son, and sibling. Each of these roles carries its own expectations and demands, forcing you to learn how to communicate effectively in each one, often at the same time.

Emotional Complexity.It is commonly thought that people should feel only positive emotions toward their family members (Berscheid, 2002). As psychologist Theodor Reik (1972) notes, people are “intolerant of feelings of resentment and hatred that sometimes rise in [them] against beloved persons—we feel that such an emotion has no right to exist beside our strong affection, even for a few minutes” (pp. 99–100). Yet members of the same family typically experience both warm and antagonistic feelings toward one another (Silverstein & Giarrusso, 2010). That’s because family members get into conflicts, just as do people in any other type of relationship. Personality differences, contrasting interests and priorities—all of these can create tensions that fuel resentment and other unpleasant emotions among family members. But if you believe you’re not supposed to feel angry or frustrated with your family, this sense of wrongness can make these emotions seem even more intense. Thus, two things you can do to improve your family relationships are to realize that it’s perfectly normal to not always get along, and to accept the complexity of emotions that will naturally occur within such involvements.