Evaluating Your Resources

Today, anyone can publish a book, an article, or a Web site given a little time and the right equipment. So it’s a good idea to maintain a healthy skepticism about the sources you find for your speech. No matter where your research is from, you need to evaluate it by considering these five factors: relevancy, currency, authority, objectivity, and consensual validation.

Relevancy.Consider the degree to which your source is related to your speech’s specific purpose. You can waste a lot of time sifting through and reading material that barely touches on your topic. Take, for example, an informative presentation for your art history class about the use of color in French Impressionist paintings. Your research could lead you to hundreds of books, articles, and online materials about French impressionism. To eliminate irrelevant resources, stay focused on your specific purpose—the use of color in such art.

Currency.For some speech topics, it’s critical to have the most current information available. Publication dates of magazines, newspapers, articles, and books are relatively easy to determine, but some Web sites present a different challenge. Try to determine when a site was last updated—check for timely commentary, copyright dates on the home page, or dates of individual posts. Avoid relying on information from any Web site that hasn’t been updated in several months. Any site with broken hyperlinks is probably outdated.

Authority.For each resource you find, ask yourself, What are the author’s credentials? To determine this, find out qualifications the creator brings to the work, such as personal experience, a prolonged professional career, or relevant academic degrees from a respectable educational institution. You can usually find information about an author’s credentials within the first few pages of a book or in a footnote or biographical note in an article or another document.

For an online source, consider the reputation of the sponsoring organization. For example, information found on the American Medical Association (AMA) Web site has authority because of the AMA’s reputation as a medical organization. You should also look for footnotes or works-cited listings. Check out those sources to see if they look valid. Often, an online post will link to more information about the author, providing you a chance to check out his or her credentials. Finally, use your instincts to judge the look and feel of the site. Although appearance should never be the sole indicator of authority, mistakes and sloppiness suggest a lack of authority.

Objectivity.You want to use objective research sources—those based on facts, not bias. Of course, all sources have some degree of bias. But you want to avoid blatantly one-sided or propaganda-like resources, whose sole purpose is to convey the author’s point of view or a particular ideology.

LearningCurve can help you review! Go to bedfordstmartins.com/

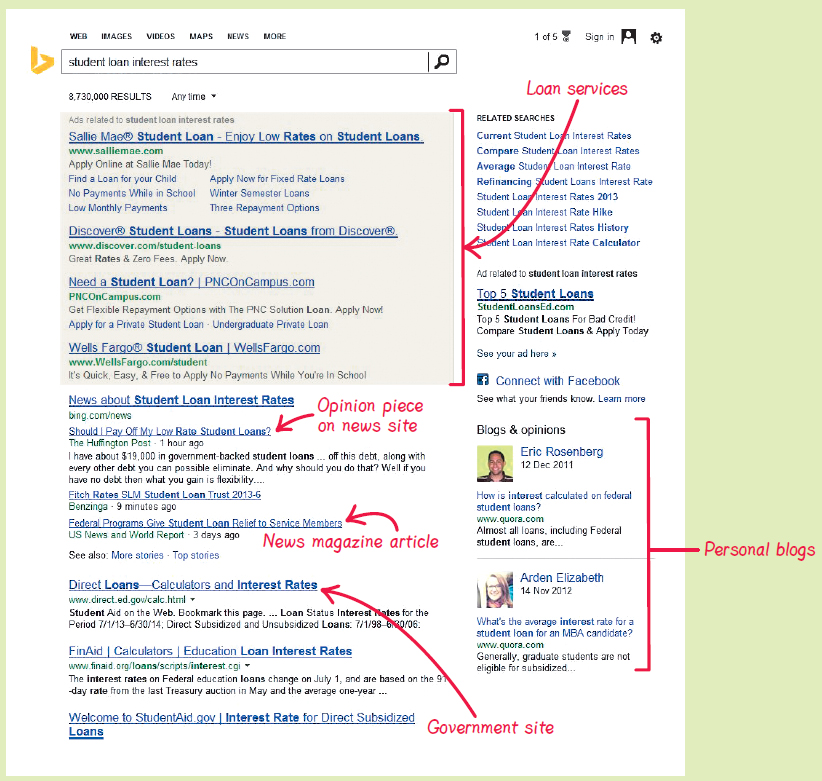

If the resource is a Web site, click on the “About” link, which should take you to a page describing the mission and purpose of the group or organization that publishes the site. Review this information to see if the site is pushing a particular agenda. Also, examine any external links on the site to see what types of organizations the group associates with. Do these associa-tions suggest possible bias? Finally, don’t over-rely on commercial Web sites (.com); these sites usually exist to sell or promote some product or service.

Consensual Validation.A resource has consensual validation when other sources agree with or use the same information you’re considering using. Consensual validation suggests that the information (especially that found on the Web) is reliable. For instance, imagine you’re researching drinking in college. You come across a Web site that defines binge drinking as men drinking five consecutive alcoholic drinks or women consuming four consecutive alcoholic drinks. You ask yourself, What kind of alcohol, and over what period of time? What’s the original source of this information? As you research a bit further by consulting library databases, you find several studies conducted at Harvard that use the same definition of binge drinking but that provide more details that answer your questions. You now have confidence in the original information as well as additional details to use in your speech.

WHAT YOU GET IN SEARCH RESULTS