4.1 Thinking About Nature and Nurture: Two Tales

The first tale concerns a familiar psychological quality: intelligence. Consider this question:

Which is the more important cause of individual differences in intelligence: (1) inheritance (nature) or (2) experience (nurture)?

Once you learn to think like a psychologist about nature and nurture, you won’t answer simply “#1” or “#2.” Here’s a study that shows why.

Genes, Intelligence, Poverty, and Wealth

Preview Question

Question

What explains intelligence? Nature? Nurture? Both?

What explains intelligence? Nature? Nurture? Both?

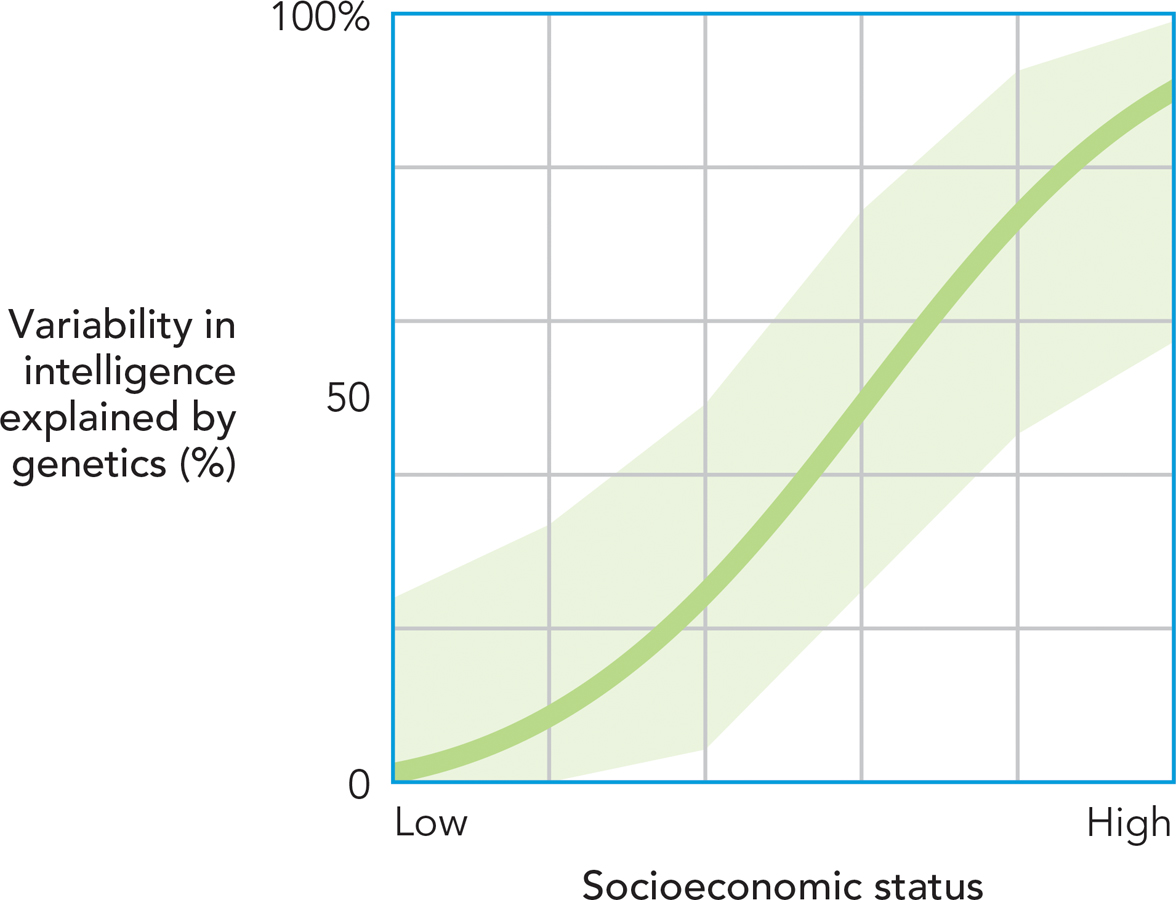

In 2003, a team of psychologists (Turkheimer et al., 2003) studied intelligence in a large population of twins. They measured intelligence in pairs of (1) identical or monozygotic (MZ) twins, who have the same genes, and (2) fraternal or dizygotic (DZ) twins, who share only half their genes. By comparing MZ and DZ twins, they could determine the degree to which genes influence intelligence. (We’ll explain later exactly how this comparison is done.)

In addition, the researchers measured each twin pair family’s socioeconomic status (SES), which is an index of family wealth, parents’ level of education, and the quality of jobs held by the parents. Because socioeconomic status shapes the environment twins experience once they are born, it is an aspect of nurture.

Why did the psychologists measure SES? They did so thanks to a critical insight into the question stated above; they realized that the question “Which is more important, nature or nurture?” might not be a good one. Its wording suggests that there is a single correct answer that applies to all people, in all places. But there may be no single correct answer; rather, genes might be more important in some environments and less important in others.

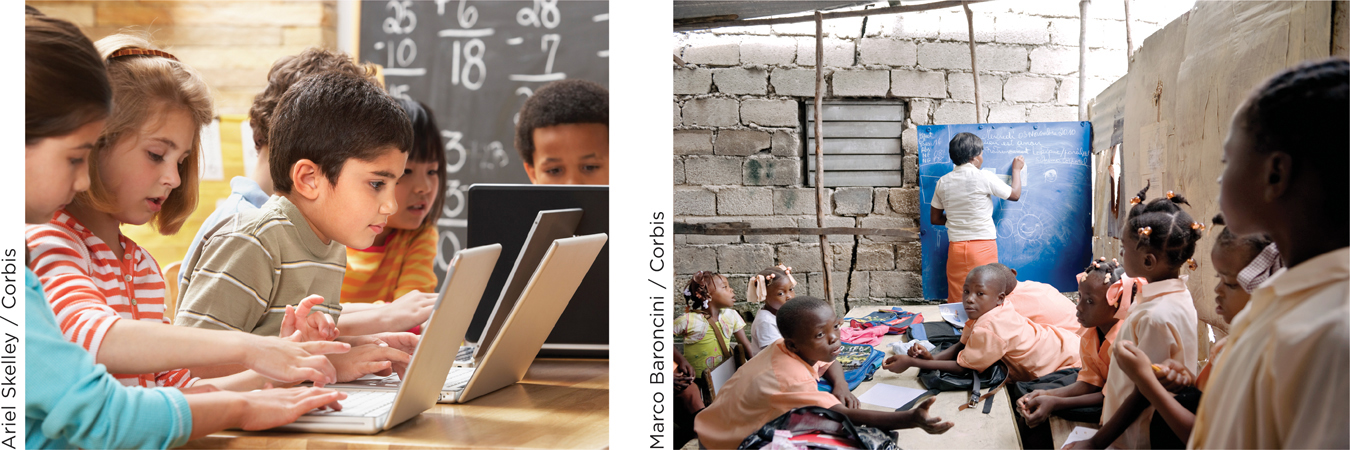

To find out, the researchers calculated the effects of genes on intelligence among people living at each of various SES levels (Figure 4.1). In high-

What features of your school or home environment enabled you to develop your intelligence or other skills?

In this case, “thinking like a psychologist” means recognizing that nature and nurture are not independent forces, each with a fixed size. It means recognizing, instead, that nature and nurture are interdependent; that is, the effect of one may depend on the other (Ridley, 2003; Russell, 2011). Our simple question above—

You’ll learn a similar lesson in our second tale of nature and nurture.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 1

For people who are very poor, genes played almost no role in shaping intelligence, whereas for people in high-

| A. |

| B. |

Cultural Practices and Biological Evolution

Preview Question

Question

What can lactose intolerance tell us about whether biology or culture came first?

What can lactose intolerance tell us about whether biology or culture came first?

“Which came first, the chicken or the egg?” That’s a tricky question. But here’s one that sounds easier: Which came first, human biology or human culture?

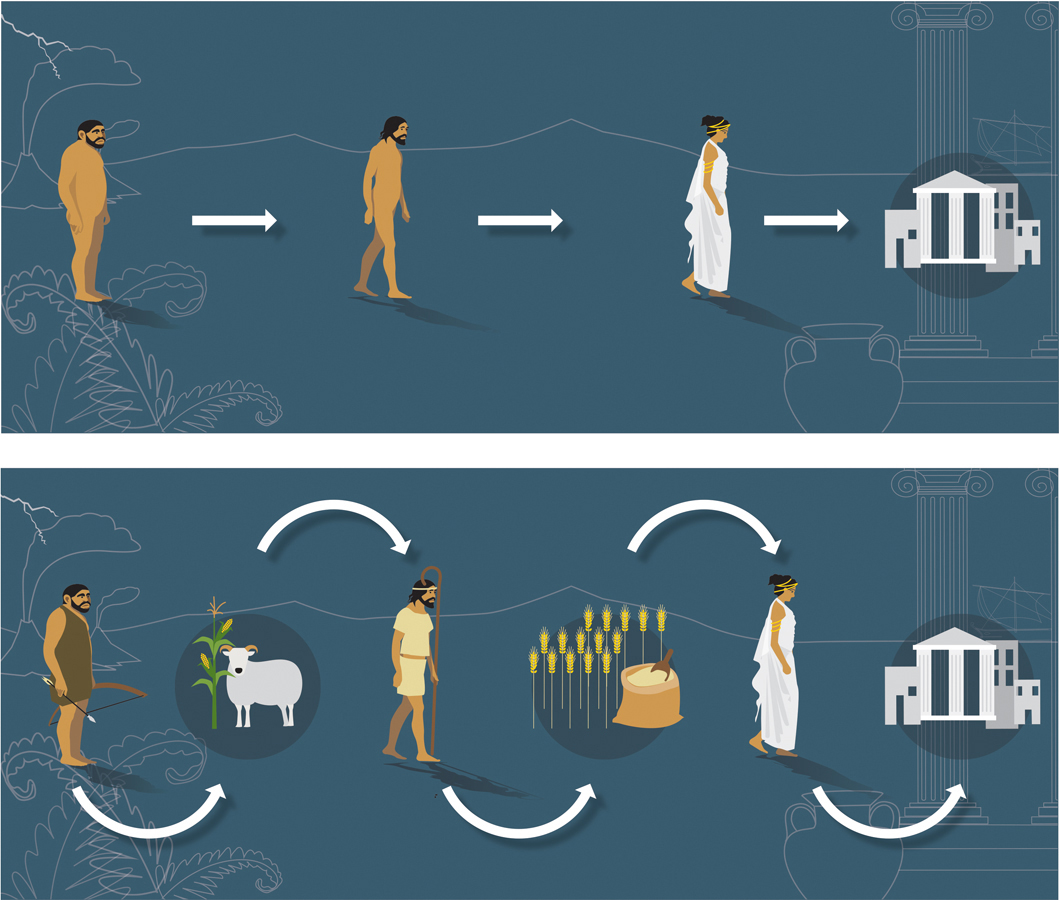

Most people would say biology. The biology of all present-

Evidence suggests, however, that this conception is wrong. Biology did not evolve first, prior to culture. Rather, biology and culture evolved together, or coevolved. Coevolution refers to processes through which biology and culture interacted in the course of human evolution (Durham, 1991; Figure 4.2). In coevolutionary processes, human biology evolves, in part, in response to the cultural practices that generation after generation of humans encounter.

Coevolution is evident in a behavior common to many—

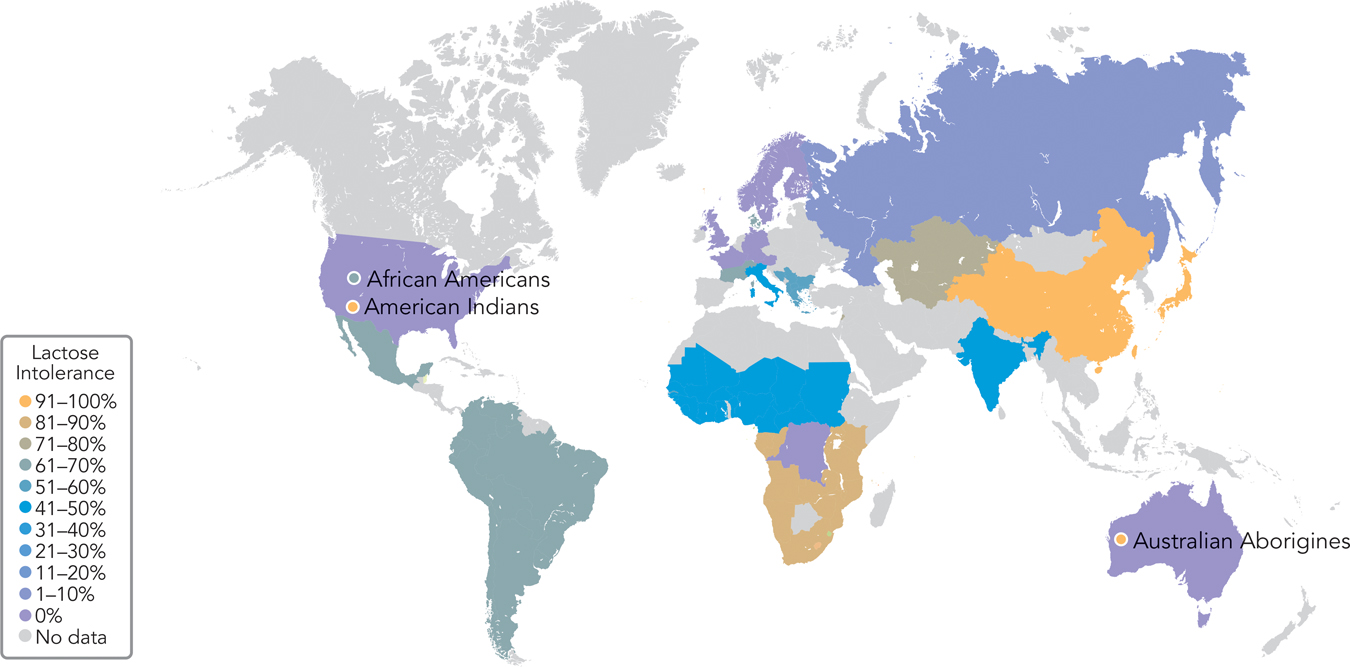

At a biological level, genes explain variations in lactose tolerance (Laland, Odling-

What accounts for this biological difference of having the genes or not? Culture! Cultural differences created the differences in biology (Durham, 1991; Laland et al., 2010). Here’s how it worked. Across thousands of years of evolution, different cultures developed different ways of producing and preparing food. One major difference involved milk, for which there were three main cultural practices:

Raise dairy cows and serve milk. In some cultures (e.g., in Northern Europe), people raised dairy cows, milked them, and encouraged the drinking of milk.

Raise dairy cows and serve cheese. In other cultures (e.g., in Southern Europe), people raised and milked cows, but turned much of the milk into cheese, which contains less lactose than raw milk.

Don’t raise dairy cows. In yet other cultures (e.g., those of East Africa), people did not raise dairy cows. This was a wise choice; in hot, moist climates, dairy cows attract insects that carry disease, so raising them can be detrimental to human health. In these cultures, milk was not part of the diet.

In regions of the world with cultural practice #1, people who could digest lactose had an evolutionary advantage. They got nutrients from milk, grew stronger, and thus were more likely to survive and reproduce. Across generations, the population contained more and more people who were lactose tolerant (because more and more of them were surviving and reproducing). Today, almost everyone is lactose tolerant in those regions of the world.

In regions with cultural practice #2, the ability to digest lactose was less of an advantage. People who had trouble digesting milk could still get nutrition from cheese. Today, in these areas of the world, about 50% of people are lactose tolerant.

In regions with cultural practice #3, the ability to digest lactose had no evolutionary advantage (because there was no milk). As a result, that biological ability did not evolve. Today, only a very small number of people in these parts of the world are lactose tolerant.

We see, then, that in the course of human evolution, neither biology nor culture “came first.” Biology and culture were intertwined. Biology evolved, in part, in response to cultural practices.

Once again, “thinking like a psychologist” does not mean settling on one versus another answer to our question (“Which came first, human biology or human culture?”). It means rejecting the question as simplistic. As you learn about the way genes and environments interact, you’ll learn to ask smarter, more sophisticated questions about nature and nurture. You, too, will learn to think like a psychologist.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 2

In what cultural context would the ability to digest lactose be an evolutionary advantage? How does this illustrate the idea that biology and culture are intertwined?

The Moral of the Stories: Nature and Nurture Interact

Preview Question

Question

What does it mean to say that nature is dependent on nurture?

What does it mean to say that nature is dependent on nurture?

These two stories, about intelligence and lactose tolerance, have the same moral: Nature and nurture interact. People’s psychological and biological characteristics reflect a combination of the two. Although we haven’t yet analyzed genetic mechanisms at a detailed biological level (that happens later in this chapter), you can already see what that analysis has to explain: the interaction of genes and environmental influences.

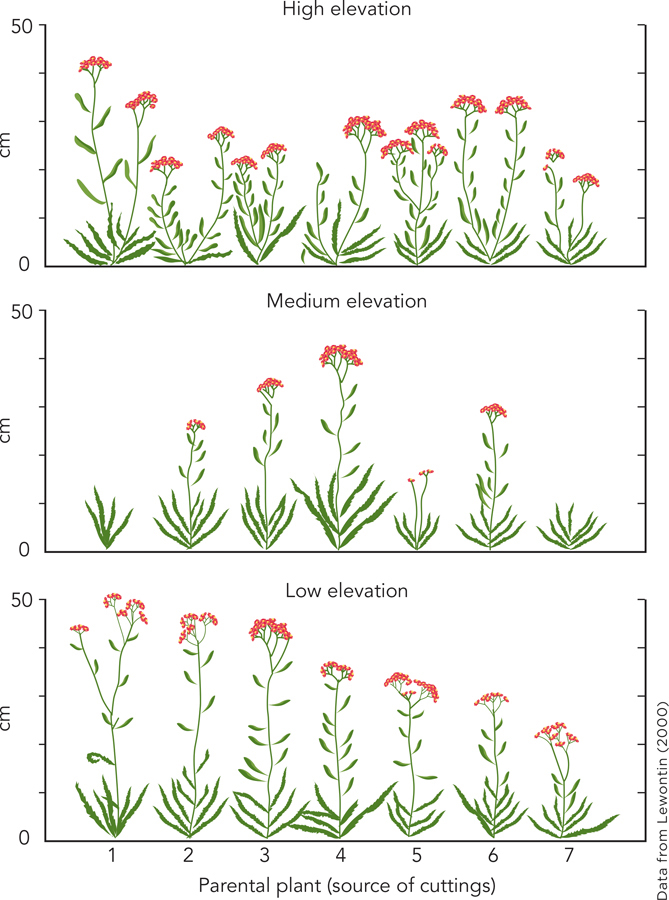

Before we return to the psychology of humans, we note that gene–

Which was more important to plant growth, nature or nurture? Looking at the plants, that question hardly makes sense. Different environments (nurture) made little difference to some plants (e.g., #4) but greatly affected others (e.g., #1). Some genetically based differences seen in low elevation (e.g., plant #3 taller than #6) reverse at high elevation (#6 taller than #3). At both low and high elevations, plant #1 was the tallest of the seven, but at medium elevations, it was the second shortest. To predict the height of the plants, you need to know about their genes and their environments.

For some characteristics, genetic influences are predominant and environmental influence is negligible. Eye color, for instance, is determined overwhelmingly by genes (Zhu et al., 2004). For other characteristics, the reverse is true. As you saw earlier, among people living in poverty, environmental effects on individual differences in intelligence are large and genetic effects are small (Turkheimer et al., 2003). Yet, in general, both nature and nurture are influential and, to understand their influence, must be considered together.

The nature–

—Paul Ehrlich (2000, p. 10)

With that lesson in place, let’s look at nature, nurture, and individual differences in psychological characteristics.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 3

Some traits, such as eye color, are determined overwhelmingly by . However, for other traits, such as intelligence, the effect of genes largely depends on the in which one is raised.