4.2 Nature, Nurture, and Individual Differences

Why do people differ so much? Some are outgoing and others shy, some are intelligent and others less so, some are politically conservative and others liberal. One possible explanation is inheritance. In the field of behavior genetics (Kim, 2009), researchers try to determine the degree to which individual differences in the behavior of animals (including humans) are inherited—

Twins and the Twin Method

Preview Question

Question

How can identical and fraternal twins’ data be used to tell us about the influence of genes?

How can identical and fraternal twins’ data be used to tell us about the influence of genes?

128

Twins are just what the behavior geneticist needs: people whose degree of genetic overlap is known. Humans share most genes, yet we all differ from one another a little bit; you aren’t exactly the same, genetically, as your friends and neighbors. Finding out exactly how much your genes that can vary overlap with these other people would require a lot of work: time-

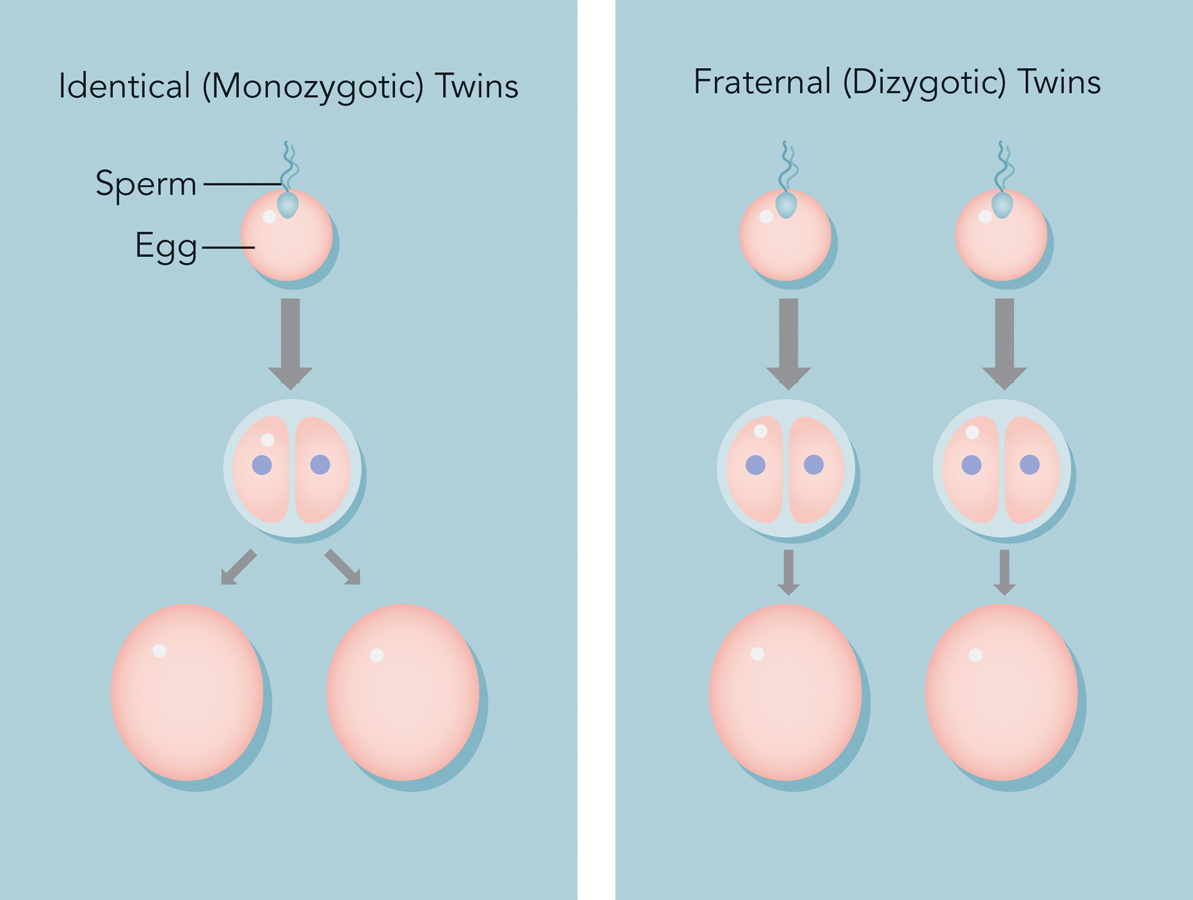

MZ and DZ twins’ varying genetic overlap results from differing biological events at the point of conception (Figure 4.5):

Monozygotic twins are produced when one zygote, the initial cell capable of developing into a complete organism, splits and forms two embryos.

Dizygotic twins develop when, through fertilization, two separate zygotes are formed.

Knowing the degree of genetic overlap makes life easy for the scientist. Through a relatively simple procedure known as the twin method, researchers can compute the degree to which genes account for individual differences. Let’s see how the twin method works.

The study of twins is similar—

One factor varies: the degree of genetic similarity in MZ and DZ twins.

Other factors are controlled: For any given twin pair, MZ or DZ, the two twins are born at the same historical period; have parents of the same age and parenting skill; experience the same environmental settings—

schools, neighborhoods, SES, and so forth. (This is true except in rare cases in which twins are adopted and raised separately.)

In an experiment, the researcher manipulates the independent variable. In a twin study, the variation of course occurs naturally. But in both cases, a researcher can determine whether the varying factor influences the outcome of the study, that is, its dependent variable.

Do you know any identical twins? How similar are they psychologically? Are they equally intelligent? Do they have the same exact personality traits?

In a twin study, the key outcome is the degree to which the co-

129

In the twin method, researchers determine the degree to which genes contribute to individual differences by following a three-

Measure a psychological characteristic in a group of MZ twins and a group of DZ twins. You could measure any characteristic discussed anywhere in this book: intelligence, personality, social attitudes, depression, eyesight, and so forth.

Compute two correlations, one for the MZ twins and one for the DZ twins. The correlations (see Chapter 2) are a numerical index of the MZ twins’ and the DZ twins’ degree of psychological similarity on the characteristics measured in Step 1.

Compare the MZ correlation with the DZ correlation. If the MZ correlation is larger than the DZ correlation, this means that genetics had an effect: The greater genetic overlap of the MZ twins caused them to be more similar to one another psychologically.

The difference between the MZ and DZ correlations indicates the degree of heritability of the psychological characteristic that was measured. Heritability is the degree to which individual differences in a characteristic—

Let’s see what heritability actually turns out to be by examining some research results.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 4

ErBV9e4Kn4RDVXUk6h7VPj90ZiMIoZ88LHej5FZX8W/tRRWAn/MIGrwx9qEEImSmiOK+p53Y19riWC2cRhZVrUGJzIvHsb46W0waGtSDeizPs03SKLwmNLLxzpTfALfVvN4Pi2hONOdkYrrqNYrWqC4knhrmnw2pJMKmqQ==The Heritability of Psychological Characteristics

Preview Question

Question

What do twin studies tell us about the heritability of personality, psychological disorders, and intelligence?

What do twin studies tell us about the heritability of personality, psychological disorders, and intelligence?

A great many psychological qualities are heritable. Twin studies commonly find that identical twins are more similar psychologically than are fraternal twins. Examples come from research on (1) personality traits, (2) psychological disorders, and (3) social and political attitudes.

PERSONALITY TRAITS. Genes contribute to individual differences in personality traits, that is, people’s typical styles of behavior and emotion (see Chapter 13). Within some populations and for some traits, heritability is about 50%; roughly half of the person-

Consider a study with an extraordinarily large population: 12,898 pairs of twins. They were part of a national twin registry in the nation of Sweden (Floderus-

130

In this large twin study, virtually all of the twins were raised together in the same household. What happens if they are raised separately? Researchers at the University of Minnesota (Bouchard, Lykken, & McGue, 1990) have studied more than 100 sets of twins who, due to adoption, were raised by different parents. If genes had no effect on personality, these twins might turn out to be no more similar than unrelated people. But findings show that they are similar, even though they were not raised together. On various personality measures, the correlation between the scores of identical twins raised apart was approximately r = .5—

THINK ABOUT IT

The average income of people living in Sweden is among the highest in the world. Rates of poverty and violent crime are both low. Do you think the results of the twin study conducted in Sweden would be the same in all other nations?

The heritability of personality, then, is much greater than 0%. However, it’s also much less than 100%. Identical twins raised in the same household are far from psychologically identical; the correlation between their personalities rarely exceeds r = .5 (by comparison, the identical-

Have you ever known two siblings who differ so much that you can hardly believe they are from the same family? Such differences are common. Different peer groups, different perceptions of the parents, and different parental behavior toward individual children all contribute to differences between siblings. For example, one study showed that mothers of identical twins do not always treat the twins identically; they sometimes respond in more negative, punitive ways to one twin than to the other. These differences in mothers’ style of punishment predict differences in the twins. Twins whose mothers are less punitive tend to experience more positive emotional states (Deater-

Does it surprise you that mothers of twins do not always treat their twins identically?

131

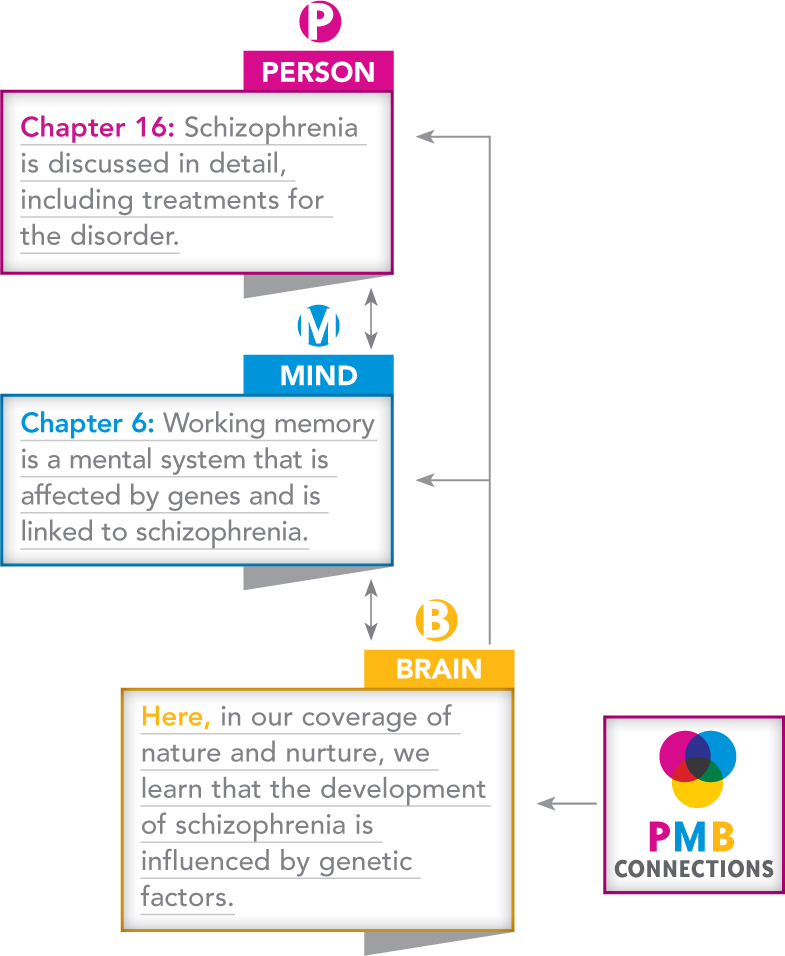

CONNECTING TO WORKING MEMORY AND SCHIZOPHRENIA

PSYCHOLOGICAL DISORDERS. Genes affect not only everyday personality traits. They also contribute to psychological disorders, that is, prolonged experiences of psychological distress that interfere with a person’s everyday life (see Chapter 15). Let’s consider a particularly severe disorder, schizophrenia.

Schizophrenia is a mental illness that creates severe disturbances in thinking and emotion (National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH], 2009). People with schizophrenia lose the normal capacity to understand the world of reality; they may experience visual hallucinations or hear voices. Often, their emotional life is disturbed (see Chapter 16).

Twin studies reveal that schizophrenia is highly heritable. More than 80% of the overall individual differences in schizophrenia (i.e., variation in whether or not a person is suffering from the disease) is caused by genetic factors (Pogue-

One way that genes are linked to schizophrenia is through working memory, a mental system used to store and manipulate information (Chapter 6). (If you multiply two numbers in your head, you are using your working memory system.) Genetic variations are related to variations in working memory ability (Goldberg et al., 2003). Low working memory ability, in turn, is common among people with schizophrenia.

SOCIAL AND POLITICAL ATTITUDES. Our third psychological characteristic, social and political attitudes, sounds like a product of nurture, not nature. Your attitudes are shaped by friends, neighbors, schools, religious institutions, community leaders, and even campaign ads. Does genetics have any influence?

It turns out that genetics does play a role. People who are more similar genetically tend to have more similar attitudes (Smith et al., 2012). In one study (Eaves et al., 1999), MZ and DZ twins reported their attitudes about social and political issues such as abortion, foreign aid, school prayer, and socialism. MZ twins were more similar than DZ twins; attitudes were heritable. Genes have less of an effect on attitudes than on personality or schizophrenia, and the environmental effects on attitudes are substantial (Eaves et al., 1999). Nonetheless, this study and others (Hatemi et al., 2009) reveal that attitudes are partly heritable.

THINK ABOUT IT

Were it not for your experiences in society—

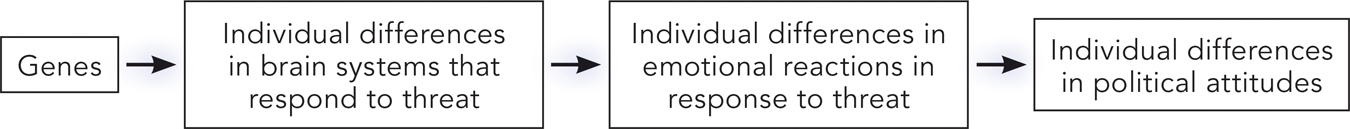

In some ways, this result is puzzling. Most of the evolution of human genes occurred tens of thousands of years ago, before there were complex societies or political institutions. How could relatively ancient genes affect contemporary political and social attitudes?

The answer is that genes do not affect social attitudes directly. They do so through indirect routes, one of which involves physical sensitivity to threatening noises and images. Researchers (Oxley et al., 2008) compared participants with strong “conservative” political views (e.g., in favor of greater military spending and the use of the death penalty, and support for U.S. actions in the Iraq War) to those with “liberal” views (opposing the same policies). They measured participants’ physiological reactions while exposing them to loud noises and to pictures displaying physical threats (e.g., a picture of a large spider on someone’s face). People with different political views responded differently. Conservatives responded more strongly to the threatening images and noises than did liberals (Oxley et al., 2008).

132

Many factors other than genetics also shape political attitudes. Nonetheless, these results help to resolve the puzzle of how genes have any influence. Genetic variations can create individual differences in neural systems in the brain that are active when people respond to threat. These brain-

How politically conservative or liberal are you? Do you think you are physiologically reactive in the way that is predicted by this research?

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 5

Which of the following statements about the meaning of heritability are true?

The greater psychological similarity of MZ twins compared with DZ twins can be taken as evidence of the environment’s effect on personality.

MZ twins are not psychologically identical, due in part to the influence of different parental behavior toward the twins, among other environmental differences.

The mental illness schizophrenia is highly heritable, partly as a result of the heritability of working memory.

Social and political attitudes are at least in part heritable, largely due to the heritability of physical sensitivity to threat.

- j5w4x7xvvq7gvAndO/AZo91eUT4UNas0ELSBSvGQD4pCJy1Lx8M5UZDZPG8QO3YLGP+XxlZEhnsNL3oy/lhOeTsysKSnCn8tlBJyi15FBGelL1dISVE0CYUeQnIOUO8SVBJJcknm2gb5OWEa0xF+zO3dN7RcRaiqdtbdRKsCX1dUo/lgia2Kpg2fpWF2RpQpXmQMAhnRQBtHTGUUSPGP/G58X1ZQ78uVKJHbXa8eblDHJfer7rT695stF1I=

- W1It72tEGKf/kHgomAtKNOHySIy7gi20MNYrG7PzBbCQLH0LsUz4tVDeNH0fSn1hPFMU7zg4HXVLjoFOKtvFHdaPaozG9LadbOVAPduqRizCjQy/32FvNVVdFUW67VLAQvZxbzTV0IDVbI0Qjk/UMCvJdEGIMsopmqTZOf59SpJom44qYz3HqCMc+fFznaYH+TTi/TRb6SzR85rnyPVt0jWma42C1Q/nk/yuiMsfNlnx6BUwpUZZS8HfBwxzKfM02b1v7anRA8vwZrkd

- Kkrmw6v1gY5dO82eXO9bfkFu5ofoz0DQfxep8EgUpSuIa1hBAJCQgNI0TQax5gohmWEh4psR8bXUqe/j5gMoW2Ul0maIsN4SnNNnI1cyoI8+wQby00GfjqFGvKxEanHsDciho8wuLeLnQAhDekQSDyetQt+c5boFZafawVRFkGZ/CcbYi5fnQT1VPsob+NRhD6OZXtMYEbRgbZR7

- vcvKUP37v1LtHj+aKvNPreeMFATEiVelPZzPYMf1DSS+w1BVCuMmWCPYZh7UfMMrfPagOwG7wZoUsaeVj/nUKr/mBfuIkAjNQiGW+UcdR3F4p1mCB95UAyMI4mC8HBJ7hD8aXuVeuqyjW43OYL6nKoYBuDoncNMVih5Lj/WlATnWftqCI6P7hZXjDAx0bEmuTCTQWmrusyhaChICaVB5SpnVOQj3cNqQpALrtiRKfIQ=

What Heritability Results Do, and Do Not, Mean

Preview Question

Question

What false conclusions should we avoid making when interpreting the results of twin studies?

What false conclusions should we avoid making when interpreting the results of twin studies?

You’ve just seen that a range of psychological qualities are at least partly heritable. People who are more similar genetically are more similar psychologically. But what, exactly, do these results mean—

What heritability results do mean is that we can reject a “blank slate” argument (Pinker, 2002; see Chapter 1). The idea that, at birth, the mind has no inborn characteristics or tendencies is contradicted by twin-

However, here are three conclusions that cannot validly be drawn from twin-

False Conclusion #1: Since psychological characteristics are heritable, they cannot change. A person’s characteristics can change enormously, even if individual differences are heritable. Heritability and changeability can go hand in hand—

133

False Conclusion #2: 50% heritability for a trait means that half of each individual’s trait is inherited. Statements about heritability are statements about individual differences in the population. Heritability percentages do not describe individual people. For instance, personality is 50% heritable, but that does not mean “half of one’s personality is inherited.” The word “half” does not refer to anything in an individual person, but to differences among people in the population at large. In general, numbers that describe a population of people do not also describe each individual person in that population. For example, the average height of students in your intro psych class might be 5´6˝, but it’s possible that no individual person is actually 5´6˝ tall.

False Conclusion #3: If heritability within two groups is high, and the groups differ, then the differences between the groups are due to genes. Heritability describes the influence of genes within a group. Even if heritability is high, differences between groups may be due to the environment, not inherited biology. Consider physical height among citizens of South Korea and North Korea. Within each population, 80 to 90% of the variation in height is heritable. People in one population (South Korean) are much taller than in the other. But the difference between the populations is not caused by genes. It can’t be; no fundamental genetic difference exists between the populations, both of which are of Korean ancestry (Johnson et al., 2009). Group differences are caused by an environmental factor: Nutrition and overall living conditions are poor in North Korea compared with South Korea.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 6

Which of the following statements about the meaning of heritability are true?

Even if a trait is highly heritable, it can still change.

Learning that heritability for a trait is 75% means that three-

quarters of your personality is inherited. Even if heritability for a trait is high, two groups could differ on that trait because of environmental factors.

- rp7xsADncvGA3QtQ7IxLoas533xEs9p027n0v5tVpvxDBi8FVQbX9nHR32djwBYbBNjmo3a2WUPcEnTkZgYGlzaOfw4aBnKOFZGBs3MyE18aNskz4HtIC9/5ymNZxCEYk88ABk37szo=

- wz+NvIRumyIQ3qYaPm3CL4kBLFIRMN8BFHlUOD+3rAJ/Q4eSnD+dnPDwa/tcmLXuOhTfC0Mzn/ml5mVAgDbeSFOhhDO5OJnI6F1CPy4T6f6gH3XAbXhGmImV1RTuJtnQi9Ixp5cgZbO4Tyu33/ix43Sex87YaHPYB85mQ3rT75Dshu4gb6zbYXWxkukARtQuT1j6f1K3UQ0=

- yIrQPyE5zdUWJQTb8Hssw/+En6mmjp9y6ND6fChnilV777RbAfjj5ZBxOoy3MsMWdIs7s8QlPqK8zdFodewyQ5Q+sjejhy8ODS0LVyU9Kun9/MUhKjAzjhEP2JOHRD+QGiPEHQJ2BpFuee9e17VY+nZwiK+A9KrEunsSrtWA0M5evBe7bhU54BZNs0tsZIhst3T4OczNS7t2yHj6kE3yaA==

THINK ABOUT IT

Beware the fallacy of division, an error in which statements about a population (i.e., a large group of persons or things) are thought to apply to each of the individuals in the population. In reality, a population-

134