4.5 Nature, Nurture, and the Brain

Thus far in this chapter, we’ve primarily focused on two of the three levels of analysis in psychology: the person and the mind (see Chapter 1). You first saw how nature and nurture affect qualities of people, such as their intelligence, personality, social attitudes, and experience of psychological disorders. You then saw two analyses of mind: “mental-

Genes and Brain Structure

Preview Question

Question

How do genes shape brain development?

How do genes shape brain development?

You have a human brain because you have human genes. The brain, like other structures of the body, requires the genetic code of DNA for its development. Yet the story of how the brain develops is not a story of genes alone. A little bit of counting shows why.

The total number of genes in the human genome is surprisingly small: not millions of genes, but about 25,000 of them (Pennisi, 2005). The total number of neural interconnections in the brain is astronomically large: not millions or even billions of connections, but trillions of them. The human brain contains about 100 billion neurons, and a typical neuron might connect to a thousand other neurons (Penn & Shatz, 1999), resulting in trillions of points at which one brain cell signals another.

Now compare the numbers. Genes can’t possibly determine exactly which neurons connect to which other neurons; there isn’t enough information in the genetic code. The big puzzle in the study of nature, nurture, and the brain is the question of how the brain gets “wired up.” What determines which neurons connect to which other ones, forming the network of brain communications that enable us to think and feel?

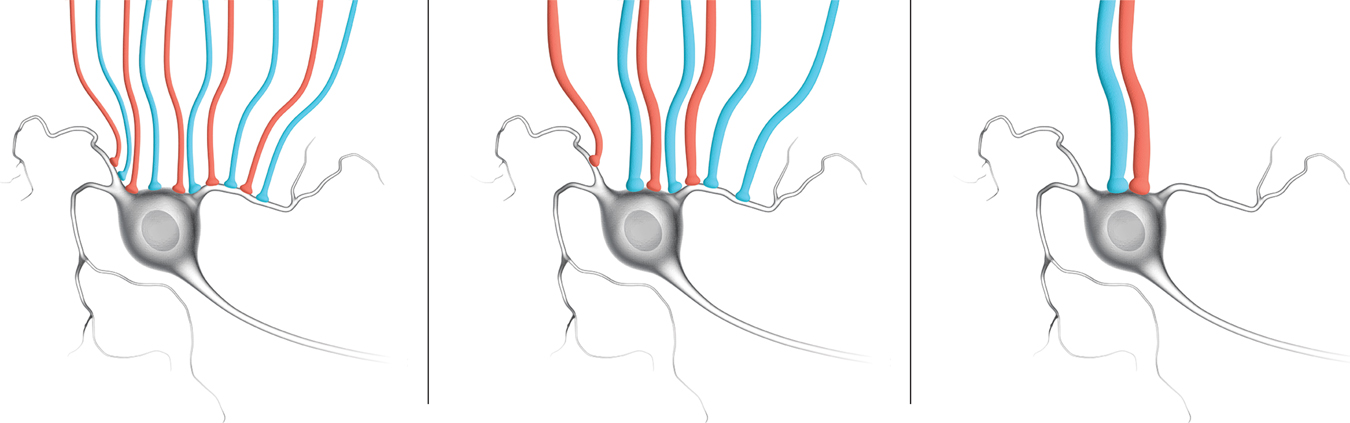

Genes are key to the first stage of the brain’s wiring process. Genetic information causes neurons to connect from one general region of the brain to another; for example, from a region that receives information from the eyes to a region in the rear of the brain that processes visual information. However, these region-

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 15

Why can’t genes entirely determine which neurons connect with which other neurons?

Environmental Experience and Brain Structure

Preview Question

Question

How does environmental experience shape brain development?

How does environmental experience shape brain development?

The brain needs stimulation from the outside world. Experience—

EXPERIENCE AND CONNECTIONS AMONG BRAIN CELLS. Environmental stimulation activates neurons, the cells of the brain. This activation alters the way in which neurons connect to one another. The principle guiding the development of these connections is expressed in a simple phrase: “Neurons that fire together, wire together” (Edelman & Tononi, 2000, p. 83). When environmental stimulation causes a group of neurons to fire at the same time, the interconnections among those neurons grow stronger.

What about neurons that don’t fire together? Their connections grow weaker. The brain “prunes” connections among brain cells that are not needed (Ruthazer & Aizenman, 2010); through neural pruning, unneeded connections among brain cells are eliminated. (The process is called “pruning” because it’s similar to how a gardener might prune away unwanted branches of a plant.) By strengthening connections that are used as the organism interacts with the environment, and by pruning away connections that are not used, the brain adapts to the environment (Schwartz, Schohl, & Ruthazer, 2011). Brain connections, then, are not fully specified in the genes. They are sculpted through experience.

The process of neural pruning has a surprising implication. The time of your life at which you have the most interconnections among the cells of your brain is when you are born. With experience, unused connections are pruned away (Kanamori et al., 2013; Low & Cheng, 2006; Figure 4.12), leaving you with a brain that more effectively and efficiently processes information from the environments you experience frequently.

What happens when the developing brain is not sufficiently stimulated? Connections among brain cells do not form at a normal rate. As a result, a person’s abilities to think and act are impaired. The brain needs environmental interaction to develop properly. Cases of childhood neglect show what happens if these interactions are lacking. Babies who spend most of their time by themselves in cribs, with little interaction with others, develop more slowly. They fail even to perform simple behaviors, such as sitting up and walking, in the same manner as children who experience more stimulating environments (Shatz, 1992).

What kind of environmental interaction do you suppose is optimal for proper development? Does television provide enough stimulation?

Experimental research confirms that the brain needs experience. Classic research explored the development of the brain’s visual system, that is, the brain region that processes information coming into the brain through the eyes. Researchers performed a surgical procedure in which they closed one eyelid of a young monkey (Weisel, 1981), preventing the monkey from receiving normal environmental stimulation to that eye. A few months later, they surgically opened the eyelid. The eye itself was unharmed by this procedure, yet the monkey could not see out of the eye. Why not? Although the monkey’s eye was biologically normal, its brain was not. Without environmental stimulation, the region of the brain that processes signals from the eye did not get properly wired up. To develop properly, the brain needs to experience the world.

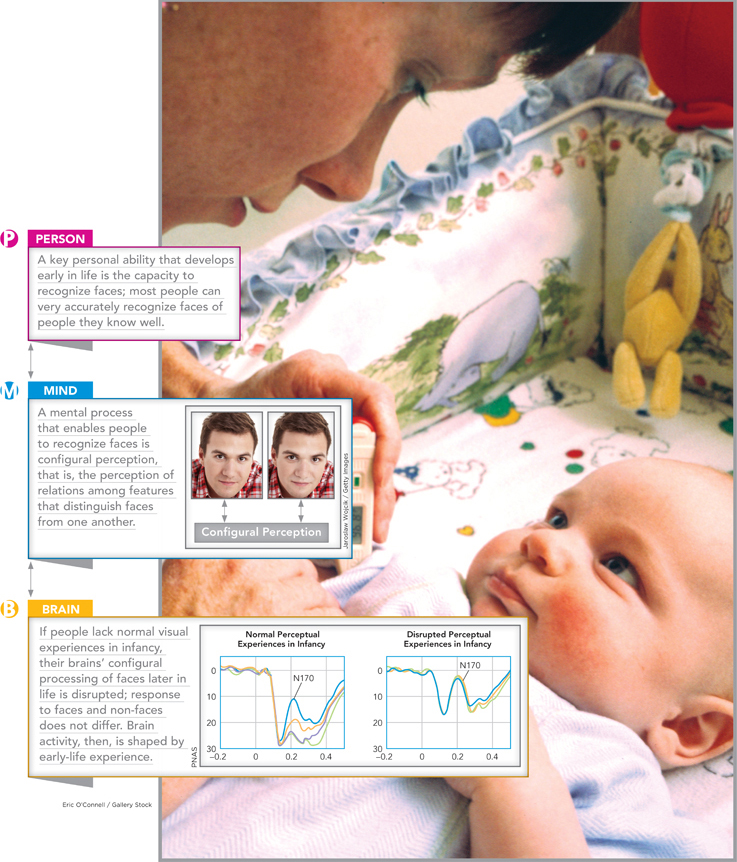

The brain’s need for environmental experience also is evident in the development of a specific human visual ability, facial recognition. People are remarkably good at recognizing faces (see Chapter 5); for instance, you would recognize an old friend instantly, even if you had not seen him or her for years. In part, this ability is a product of evolved biological nature; over the course of evolution, the ability to distinguish friends and family from strangers was important to survival. Yet the ability also is shaped by nurture. For it to develop, a person must interact visually with the social world during infancy. People lacking these interactions do not develop normal face perception; in particular, they do not developed accurate “configural” facial perception, that is, perception of the relations among facial features (e.g., distance between eyes) that distinguish one face from another (Borjon & Ghazanfar, 2013; Maurere, Le Grand, & Mondloch, 2002).

Brain research confirms that environmental experience impacts the ability to perceive faces. Researchers recorded electrical activity in the brain while participants looked at images of four types: faces, houses, visually scrambled faces, and visually scrambled houses (Röder et al., 2013). The participants included groups whose visual experiences during infancy were either (1) normal or (2) disrupted due to cataracts (a medical condition that impairs vision) that were surgically corrected later in life. Brain activity in the groups differed. Among individuals with normal experience during infancy, brain activity in response to faces was distinctive, that is, it differed from activity when houses or scrambled faces were viewed. But among people whose visual experiences in infancy had been disrupted, brain activity in response to faces was not distinctive; their brains reacted in the same manner to faces as to houses (Figure 4.13). Early-

EXPERIENCE, GENE EXPRESSION, AND BRAIN DEVELOPMENT. Recent research reveals the biological steps through which experience influences the connections among brain cells. What do you think those steps might be? Hint: You learned about a key step earlier in this chapter.

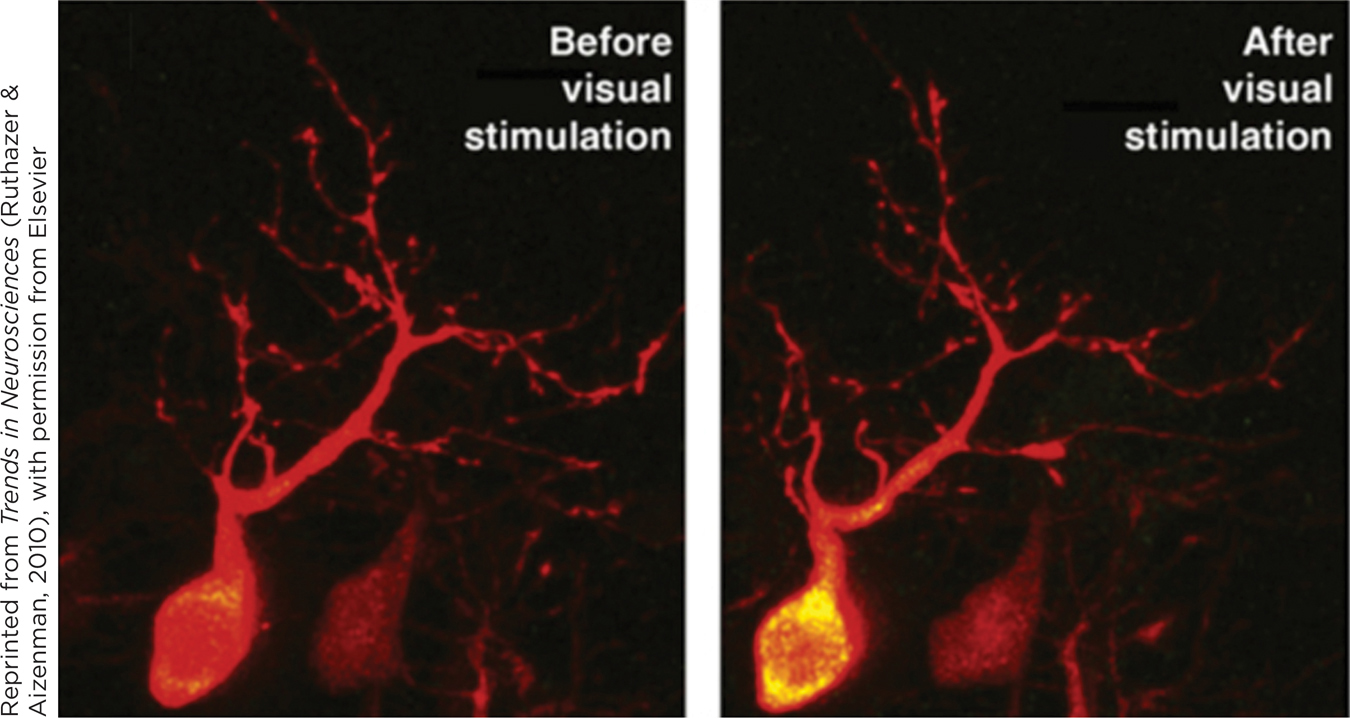

Environmental experience affects neural connections by influencing gene expression, the process in which instructions encoded into DNA are put into action to produce proteins. As you learned, environmental experiences can determine when gene expression occurs; experiences can “switch on” genes. When the “switching on” occurs within brain cells, environmental experience can alter the cells’ connections with one another. Let’s see how this works in the brain’s visual system.

Researchers have found that visual stimulation affects gene expression within brain cells that process visual information (Ruthazer & Aizenman, 2010). Thanks to powerful microscopes, you literally can see how this works. Look at the images in Figure 4.14, which show the same brain cell before, and after, a mouse received visual stimulation. Stimulation from the environment affects the inner chemistry of the cell. When the eyes opened, this stimulated a key brain chemical that moved into the main body of the brain cell (the glowing part of the image on the right) and altered gene expression. The altered gene expression, in turn, contributes to the “pruning” of neural connections; connections that are not required for good vision are pruned away. As a result, the animal’s vision improves (Schwartz et al., 2011).

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 16

The phrase “Neurons that fire together, together” refers to the idea that when environmental experience causes neurons to fire simultaneously, their interconnections strengthen. Without sufficient environmental experience, neurons may be eliminated in a process called neural . Environmental experience influences brain development via expression.