5.9 Attention

Wherever you are at the moment, there are a lot of objects to see, but you’re only looking at one of them. There are probably a lot of sounds, too—

What features of the environment are competing for your attention right now?

Attention takes effort (Kahneman, 2011). Although some occurrences (e.g., a sudden loud noise) do “grab” your attention, often you have to exert effort to keep your mind from wandering. Even when you want to, it can be difficult to fix your attention on a rambling anecdote, a classroom lecture, or the pages of a textbook.

However, when you do exert effort, you find that you’ve got a mental power: selective attention. Selective attention is the capacity to choose the flow of information that enters conscious awareness, when more than one flow of information exists in the environment. Thanks to selective attention, if there are 3 people talking at once, or 8 people out on a dance floor, or 22 people running around a football field, you can “zoom in” mentally on any one of them. Researchers have explored people’s ability to attend selectively to sounds (auditory selective attention) and sights (visual selective attention), as we’ll see in the closing sections of this chapter.

Auditory Selective Attention

Preview Question

Question

Do people hear only what they want to hear?

Do people hear only what they want to hear?

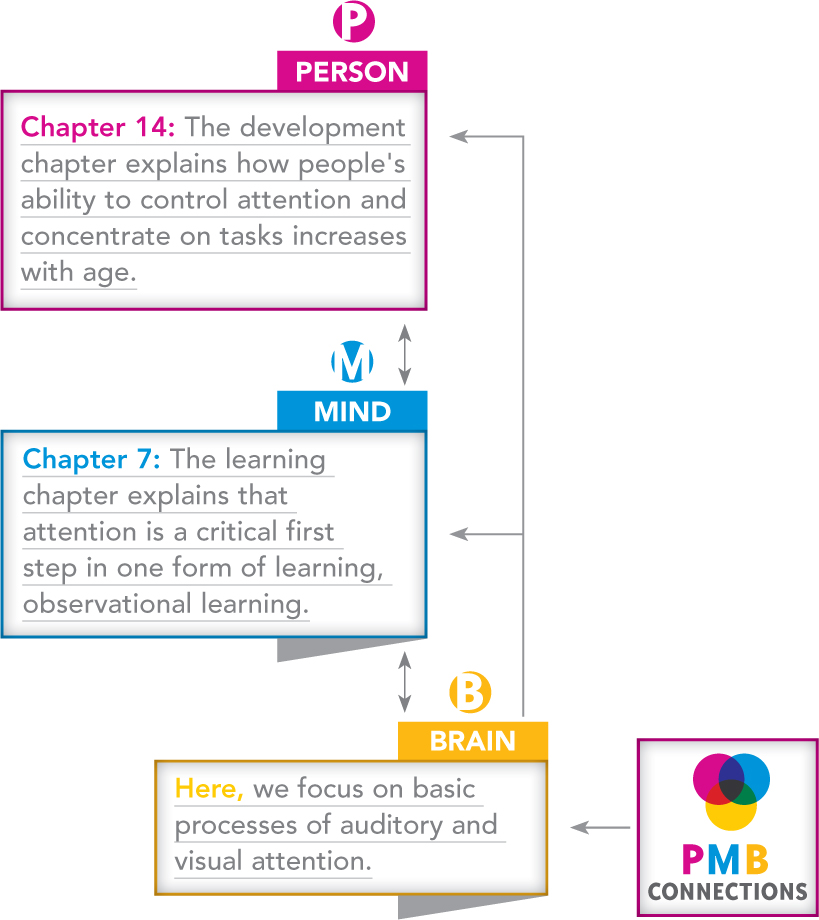

CONNECTING TO OBSERVATIONAL LEARNING AND TO PSYCHOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT

To study auditory selective attention, researchers ask participants to wear headphones that project different sounds—

Selective attention. Most people find the task to be easy. They have little trouble tracking the sounds coming into one ear, despite the potential confusion of a different sound stream entering the other ear.

Unawareness of unattended information. People usually pick up very little, if any, of the information entering the unattended ear. Although the sounds enter the ear, they are not deeply processed by the brain. People may not even notice if the spoken language in the unattended ear changes. Auditory selective attention thus enables people to pick up one flow of sounds while largely ignoring another.

Some unattended information does enter awareness. If you are listening to the information in your right ear and your own name is spoken in your left ear, you will notice it. Some personally significant information, such as your name, appears to “pop out” from the stream of unattended sound. This implies that some mental processing occurs automatically (Treisman & Gelade, 1980). Even if you are not intentionally searching for the sound of your name, you automatically will hear it.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 21

In research on auditory selective attention, what finding led researchers to conclude that some mental processing occurs automatically?

Visual Selective Attention

Preview Question

Question

Do people see only what they want to see?

Do people see only what they want to see?

The study of visual selective attention began with a research paradigm devised by psychologist Ulric Neisser and his associates (Becklen & Cervone, 1983; Neisser & Becklen, 1975). A video displayed two overlapping events: two groups of visually overlapping basketball players running, dribbling, and passing basketballs. Participants had to attend to one team, counting the number of times its team members passed the ball. At one point in the film, an unexpected event occurred: A woman carrying an umbrella walked straight across the screen. Surprisingly, hardly anyone noticed her. Although her image on the screen—

Later researchers obtained similar results with an event even more unexpected: the intrusion of a gorilla (Simons & Chabris, 1999). While two teams of basketballers played, a gorilla—

TRY THIS!

Do these selective attention experiments sound familiar to you? They should—

How could people miss a woman with an umbrella? Or a gorilla? Neisser (1976) explains that perception is guided by anticipations. People actively anticipate certain types of information. They search for the anticipated information and, if it’s there, pick it up. Unexpected information simply isn’t picked up.

Neisser’s argument underscores a general point about the material in this chapter. Perception is an active psychological activity. Your perceptions of the world reveal information about the world, and yourself.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 22

True or False?

Visual selective attention is so good that in one study, participants who watched a video of people playing with a basketball failed to notice a woman carrying an umbrella walk across the screen.

A. B. Visual selective attention is so good that, in one study, participants who watched a video of people playing with a basketball failed to notice a gorilla walk across the screen.

A. B.