Chapter 6 Introduction

If we are to understand consciousness–

– Alva Noë

MIND

6 Memory

7 Learning

8 Thinking, Language, and Intelligence

9 Consciousness

10 Emotion, Stress, and Health

11 Motivation

Memory 6

CHAPTER OUTLINE

Learning from AJ and HM

The Role of Memory in the Lives of Persons

The Varieties of Remembering

Levels of Analysis: Memory and Mind

A Three-

Stage Model of Memory Sensory Memory

Short-

Term (Working) Memory THIS JUST IN: Sources of Information and Short-

Term Memory Long-

Term Memory

Models of Knowledge Representation

Semantic Network Models

RESEARCH TOOLKIT: Priming Parallel Distributed Processing Models

Embodied Cognition

Memory: Imperfect But Improvable

Errors of Memory

CULTURAL OPPORTUNITIES: Autobiographical Memory

Improving Your Memory

Memory and the Brain

Working Memory and the Frontal Lobes

The Hippocampus and the Formation of Permanent Memories

The Distributed Representation of Knowledge

Looking Back and Looking Ahead

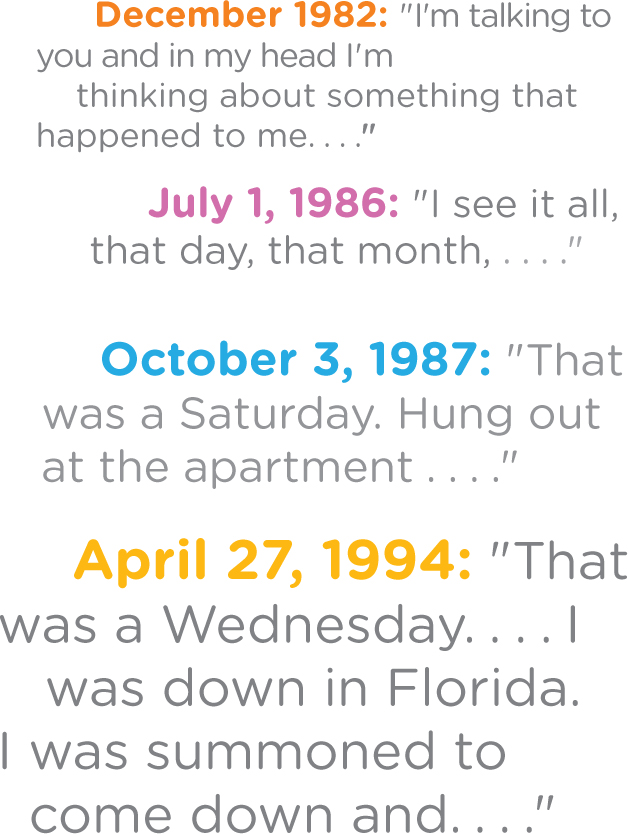

AAJ WROTE TO A PSYCHOLOGIST FOR HELP. Her problem? Too much memory. “I remember everything,” AJ reported. “I’m talking to you and in my head I’m thinking about something that happened to me in December 1982” (Parker, Cahill, & McGaugh, 2006, p. 35).

The psychologist was skeptical. Was AJ’s memory really exceptional? To find out, he gave AJ random dates and asked her to report her memories of each day (Parker et al., 2006):

July 1, 1986: “I see it all, that day, that month, that summer. Tuesday. Went with (friend’s name) to (restaurant name).”

October 3, 1987: “That was a Saturday. Hung out at the apartment all weekend, wearing a sling—

hurt my elbow.” April 27, 1994: “That was Wednesday. … I was down in Florida. I was summoned to come down and to say goodbye to my Grandmother who they all thought was dying but she ended up living. My Dad and my Mom went to New York for a wedding. Then my Mom went to Baltimore to see her family. … This was also the weekend that Nixon died.”

When psychologists checked her memories against written records, time after time, AJ’s memory was right on the mark: “highly reliable … accurate … phenomenal” (Parker et al., 2006, p. 46).

Now consider a second case: HM. In 1953, at age 27, HM underwent brain surgery to treat epileptic seizures. After the surgery, he lost the ability to remember new information; if asked what he had been doing a week, a day, or even a few minutes earlier, he could not recall (Corkin, 2002). He could remember events from his childhood (Scoville & Milner, 1957) but nothing since his surgery, which “trapped him in a mental time warp where TV is always a new invention and Truman is forever president” (Schaffhausen, 2011).

HM’s memory loss created deep personal problems. He could not establish friendships because he couldn’t recall having met a person previously. He was frequently confused—

The cases of AJ and HM are unusual. Yet they teach us lessons that apply to everyone, as you’ll see in this chapter on memory.

If you want to learn how the mind works, begin with the study of memory. It underpins so much of mental life. To speak, you have to remember the meanings of words. To solve a math problem, you need to remember rules of algebra. To motivate yourself to study, you must remember your goal of getting good grades. To experience emotions such as pride or regret, you have to remember your past behavior and your relationships to other people. Memory, our focus in this chapter, is the cornerstone of mental life. ![]()