6.1 Learning from AJ and HM

Our opening story introduced two people whose memory was exceptional—

The Role of Memory in the Lives of Persons

Preview Question

Question

What are some examples of everyday experiences that rely on the ability to remember?

What are some examples of everyday experiences that rely on the ability to remember?

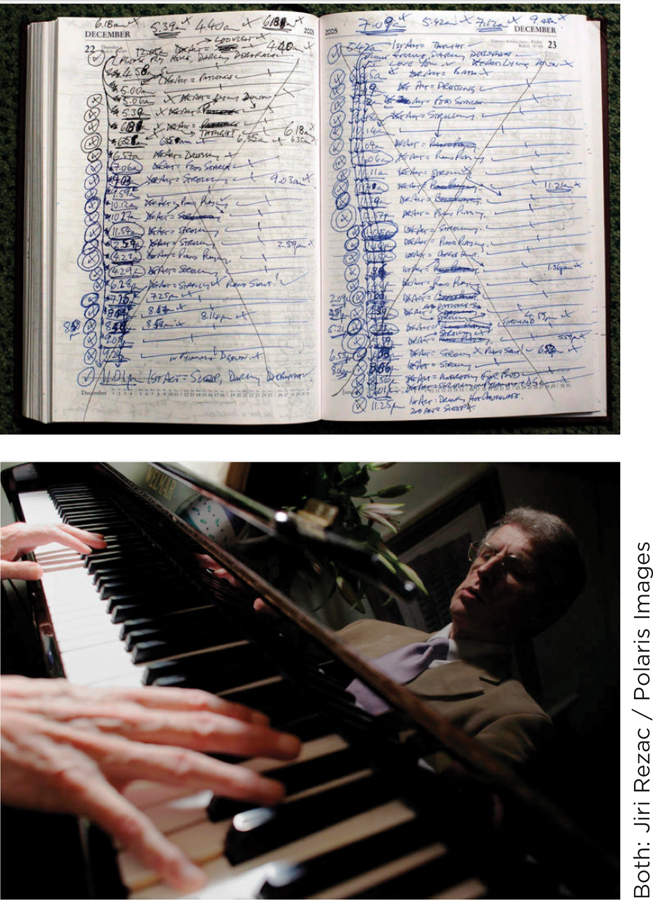

Intellectually, AJ is a perfectly ordinary person (Parker et al., 2006). Her intelligence test scores are average and her school grades were mostly Bs and Cs. Exceptional memory is her sole distinctive mental quality—

HM, too, was ordinary in many respects (Corkin, 2002). A pleasant man with a sense of humor, he had good powers of concentration and could participate in conversations (Squire, 2009). He remembered how to perform routine tasks and could navigate around his house. He lost only the capacity to form permanent memories of facts and experiences after his surgery. Yet this one loss shattered his life. Without normal memory, he could not maintain a sense of personal identity—

The first lesson learned from AJ and HM, then, is that memory is more important than one might think. You need it not only to answer questions when taking a test or playing a trivia game. You need it to be a fully human person—a being with knowledge of your past, your strengths and flaws, your roles in society, and your aspirations for the future. When memory is lost—

Memory is needed not only by individuals, but also by whole societies. Throughout human history, many societies have been oral cultures, that is, cultures lacking written forms of communication. Can these societies maintain, across generations, their cultural traditions—

The Varieties of Remembering

Preview Question

Question

What is memory, and what do the cases of AJ and HM teach us about the varieties of remembering?

What is memory, and what do the cases of AJ and HM teach us about the varieties of remembering?

The second lesson AJ and HM teach is that there are different types of memory. We will define “memory” and then explore this point in detail.

Memory is the capacity to retain knowledge. If at one point in time you know something, and at some later point you still know it, then you have remembered it.

AJ and HM show us that there are varieties of memory. Consider two questions:

Did AJ have exceptionally good memory?

Did HM lose his memory?

These questions are tricky. AJ’s memory for life events she experienced personally was exceptionally good. Yet she had “great difficulty with rote memorization” (Parker et al., 2006, p. 36), which contributed to her merely average grades in school. HM lost his ability to recall facts and experiences after his surgery, yet consider what he did not lose. HM could still participate in conversations, which means he remembered thousands of words and grammatical rules for forming sentences. He was friendly and had a sense of humor, which means he remembered social rules for interacting with people. HM also remembered how to perform everyday activities such as sitting in chairs, opening doors, and eating with utensils. He even remembered how to do crossword puzzles (Schaffhausen, 2011). For somebody who lost his memory, HM remembered quite a lot!

What activities are you engaged in now that require “how to” memory?

The fact that AJ’s and HM’s memories were exceptional in some ways and ordinary in others teaches us that there are different types of memory. A person can lose one type while retaining another.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 1

If someone can remember the personal events of her life but isn’t terribly good at rote memorization, what does that tell us about memory types?